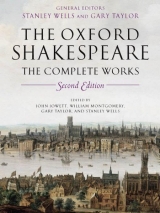

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 90 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

4.2 Enter Portia and Nerissa, still disguised

PORTIA

Enquire the Jew’s house out, give him this deed,

And let him sign it. We’ll away tonight,

And be a day before our husbands home.

This deed will be well welcome to Lorenzo.

Enter Graziano

GRAZIANO Fair sir, you are well o’erta’en.

My lord Bassanio upon more advice

Hath sent you here this ring, and doth entreat

Your company at dinner.

PORTIA That cannot be.

His ring I do accept most thankfully,

And so I pray you tell him. Furthermore,

I pray you show my youth old Shylock’s house.

GRAZIANO

That will I do.

NERISSA Sir, I would speak with you.

(Aside to Portia) I’ll see if I can get my husband’s ring

Which I did make him swear to keep for ever.

PORTIA (aside to Nerissa)

Thou mayst; I warrant we shall have old swearing

That they did give the rings away to men.

But we’ll outface them, and outswear them too.

Away, make haste. Thou know’st where I will tarry.

Exit ⌈at one door⌉

NERISSA (to Graziano)

Come, good sir, will you show me to this house?

Exeunt ⌈at another door⌉

5.1 Enter Lorenzo and Jessica

LORENZO

The moon shines bright. In such a night as this,

When the sweet wind did gently kiss the trees

And they did make no noise—in such a night

Troilus, methinks, mounted the Trojan walls,

And sighed his soul toward the Grecian tents

Where Cressid lay that night.

JESSICA In such a night

Did Thisbe fearfully o’ertrip the dew

And saw the lion’s shadow ere himself,

And ran dismayed away.

LORENZO In such a night

Stood Dido with a willow in her hand

Upon the wild sea banks, and waft her love

To come again to Carthage.

JESSICA In such a night

Medea gathered the enchanted herbs

That did renew old Aeson.

LORENZO In such a night

Did Jessica steal from the wealthy Jew,

And with an unthrift love did run from Venice

As far as Belmont.

JESSICA In such a night

Did young Lorenzo swear he loved her well,

Stealing her soul with many vows of faith,

And ne’er a true one.

LORENZO In such a night

Did pretty Jessica, like a little shrew,

Slander her love, and he forgave it her.

JESSICA

I would outnight you, did nobody come.

But hark, I hear the footing of a man.

Enter Stefano, a messenger

LORENZO

Who comes so fast in silence of the night?

STEFANO A friend.

LORENZO

A friend—what friend? Your name, I pray you, friend?

STEFANO

Stefano is my name, and I bring word

My mistress will before the break of day

Be here at Belmont. She doth stray about

By holy crosses, where she kneels and prays

For happy wedlock hours.

LORENZO Who comes with her?

STEFANO

None but a holy hermit and her maid.

I pray you, is my master yet returned?

LORENZO

He is not, nor we have not heard from him.

But go we in, I pray thee, Jessica,

And ceremoniously let us prepare

Some welcome for the mistress of the house.

Enter Lancelot, the clown

LANCELOT (calling) Sola, sola! Wo, ha, ho! Sola, sola!

LORENZO Who calls?

LANCELOT (calling) Sola!—Did you see Master Lorenzo?

(Calling) Master Lorenzo! Sola, sola!

LORENZO Leave hollering, man: here.

LANCELOT (calling) Sola!—Where, where?

LORENZO Here.

LANCELOT Tell him there’s a post come from my master with his horn full of good news. My master will be here ere morning. Exit

LORENZO (to Jessica)

Sweet soul, let’s in, and there expect their coming.

And yet no matter. Why should we go in?

My friend Stefano, signify, I pray you,

Within the house your mistress is at hand,

And bring your music forth into the air. Exit Stefano

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!

Here will we sit, and let the sounds of music

Creep in our ears. Soft stillness and the night

Become the touches of sweet harmony.

Sit, Jessica.

⌈They⌉ sit

Look how the floor of heaven

Is thick inlaid with patens of bright gold.

There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still choiring to the young-eyed cherubins.

Such harmony is in immortal souls,

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.

⌈Enter Musicians⌉

(To the Musicians) Come, ho, and wake Diana with a

hymn.

With sweetest touches pierce your mistress’ ear,

And draw her home with music.

The Musicians play

JESSICA

I am never merry when I hear sweet music.

LORENZO

The reason is your spirits are attentive,

For do but note a wild and wanton herd

Or race of youthful and unhandled colts,

Fetching mad bounds, bellowing and neighing loud,

Which is the hot condition of their blood,

If they but hear perchance a trumpet sound,

Or any air of music touch their ears,

You shall perceive them make a mutual stand,

Their savage eyes turned to a modest gaze

By the sweet power of music. Therefore the poet

Did feign that Orpheus drew trees, stones, and floods,

Since naught so stockish, hard, and full of rage

But music for the time doth change his nature.

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils.

The motions of his spirit are dull as night,

And his affections dark as Erebus.

Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music.

Enter Portia and Nerissa, as themselves

PORTIA

That light we see is burning in my hall.

How far that little candle throws his beams—

So shines a good deed in a naughty world.

NERISSA

When the moon shone we did not see the candle.

PORTIA

So doth the greater glory dim the less.

A substitute shines brightly as a king

Until a king be by, and then his state

Empties itself as doth an inland brook

Into the main of waters. Music, hark.

NERISSA

It is your music, madam, of the house.

PORTIA

Nothing is good, I see, without respect.

Methinks it sounds much sweeter than by day.

NERISSA

Silence bestows that virtue on it, madam.

PORTIA

The crow doth sing as sweetly as the lark

When neither is attended, and I think

The nightingale, if she should sing by day,

When every goose is cackling, would be thought

No better a musician than the wren.

How many things by season seasoned are

To their right praise and true perfection!

⌈She sees Lorenzo and Jessica⌉

Peace, ho!

⌈Music ceases⌉

The moon sleeps with Endymion,

And would not be awaked.

LORENZO ⌈rising⌉ That is the voice,

Or I am much deceived, of Portia.

PORTIA

He knows me as the blind man knows the cuckoo—

By the bad voice.

LORENZO Dear lady, welcome home.

PORTIA

We have been praying for our husbands’ welfare,

Which speed we hope the better for our words.

Are they returned?

LORENZO Madam, they are not yet,

But there is come a messenger before

To signify their coming.

PORTIA Go in, Nerissa.

Give order to my servants that they take

No note at all of our being absent hence;

Nor you, Lorenzo; Jessica, nor you.

⌈A tucket sounds⌉

LORENZO

Your husband is at hand. I hear his trumpet.

We are no tell-tales, madam. Fear you not.

PORTIA

This night, methinks, is but the daylight sick.

It looks a little paler. ’Tis a day

Such as the day is when the sun is hid.

Enter Bassanio, Antonio, Graziano, and their followers. Graziano and Nerissa speak silently to one another

BASSANIO

We should hold day with the Antipodes

If you would walk in absence of the sun.

PORTIA

Let me give light, but let me not be light;

For a light wife doth make a heavy husband,

And never be Bassanio so for me.

But God sort all. You are welcome home, my lord.

BASSANIO

I thank you, madam. Give welcome to my friend.

This is the man, this is Antonio,

To whom I am so infinitely bound.

PORTIA

You should in all sense be much bound to him,

For as I hear he was much bound for you.

ANTONIO

No more than I am well acquitted of.

PORTIA

Sir, you are very welcome to our house.

It must appear in other ways than words,

Therefore I scant this breathing courtesy.

GRAZIANO (to Nerissa)

By yonder moon I swear you do me wrong.

In faith, I gave it to the judge’s clerk.

Would he were gelt that had it for my part,

Since you do take it, love, so much at heart.

PORTIA

A quarrel, ho, already! What’s the matter?

GRAZIANO

About a hoop of gold, a paltry ring

That she did give me, whose posy was

For all the world like cutlers’ poetry

Upon a knife—‘Love me and leave me not’.

NERISSA

What talk you of the posy or the value?

You swore to me when I did give it you

That you would wear it till your hour of death,

And that it should lie with you in your grave.

Though not for me, yet for your vehement oaths

You should have been respective and have kept it.

Gave it a judge’s clerk?—no, God’s my judge,

The clerk will ne’er wear hair on’s face that had it.

GRAZIANO

He will an if he live to be a man.

NERISSA

Ay, if a woman live to be a man.

GRAZIANO

Now by this hand, I gave it to a youth,

A kind of boy, a little scrubbed boy

No higher than thyself, the judge’s clerk,

A prating boy that begged it as a fee.

I could not for my heart deny it him.

PORTIA

You were to blame, I must be plain with you,

To part so slightly with your wife’s first gift,

A thing stuck on with oaths upon your finger,

And so riveted with faith unto your flesh.

I gave my love a ring, and made him swear

Never to part with it; and here he stands.

I dare be sworn for him he would not leave it,

Nor pluck it from his finger for the wealth

That the world masters. Now, in faith, Graziano,

You give your wife too unkind a cause of grief.

An ’twere to me, I should be mad at it.

BASSANIO (aside)

Why, I were best to cut my left hand off

And swear I lost the ring defending it.

GRAZIANO ⌈to Portia⌉

My lord Bassanio gave his ring away

Unto the judge that begged it, and indeed

Deserved it, too, and then the boy his clerk,

That took some pains in writing, he begged mine,

And neither man nor master would take aught

But the two rings.

PORTIA (to Bassanio) What ring gave you, my lord?

Not that, I hope, which you received of me.

BASSANIO

If I could add a lie unto a fault

I would deny it; but you see my finger

Hath not the ring upon it. It is gone.

PORTIA

Even so void is your false heart of truth.

By heaven, I will ne’er come in your bed

Until I see the ring.

NERISSA (to Graziano) Nor I in yours

Till I again see mine.

BASSANIO Sweet Portia,

If you did know to whom I gave the ring,

If you did know for whom I gave the ring,

And would conceive for what I gave the ring,

And how unwillingly I left the ring

When naught would be accepted but the ring,

You would abate the strength of your displeasure.

PORTIA

If you had known the virtue of the ring,

Or half her worthiness that gave the ring,

Or your own honour to contain the ring,

You would not then have parted with the ring.

What man is there so much unreasonable,

If you had pleased to have defended it

With any terms of zeal, wanted the modesty

To urge the thing held as a ceremony?

Nerissa teaches me what to believe.

I’ll die for’t but some woman had the ring.

BASSANIO

No, by my honour, madam, by my soul,

No woman had it, but a civil doctor

Which did refuse three thousand ducats of me,

And begged the ring, the which I did deny him,

And suffered him to go displeased away,

Even he that had held up the very life

Of my dear friend. What should I say, sweet lady?

I was enforced to send it after him.

I was beset with shame and courtesy.

My honour would not let ingratitude

So much besmear it. Pardon me, good lady,

For by these blessèd candles of the night,

Had you been there I think you would have begged

The ring of me to give the worthy doctor.

PORTIA

Let not that doctor e’er come near my house.

Since he hath got the jewel that I loved,

And that which you did swear to keep for me,

I will become as liberal as you.

I’ll not deny him anything I have,

No, not my body nor my husband’s bed.

Know him I shall, I am well sure of it.

Lie not a night from home. Watch me like Argus.

If you do not, if I be left alone,

Now by mine honour, which is yet mine own,

I’ll have that doctor for my bedfellow.

NERISSA (to Graziano)

And I his clerk, therefore be well advised

How you do leave me to mine own protection.

GRAZIANO

Well, do you so. Let not me take him then,

For if I do, I’ll mar the young clerk’s pen.

ANTONIO

I am th’unhappy subject of these quarrels.

PORTIA

Sir, grieve not you. You are welcome notwithstanding.

BASSANIO

Portia, forgive me this enforced wrong,

And in the hearing of these many friends

I swear to thee, even by thine own fair eyes,

Wherein I see myself—

PORTIA Mark you but that?

In both my eyes he doubly sees himself,

In each eye one. Swear by your double self,

And there’s an oath of credit.

BASSANIO Nay, but hear me.

Pardon this fault, and by my soul I swear

I never more will break an oath with thee.

ANTONIO (to Portia)

I once did lend my body for his wealth

Which, but for him that had your husband’s ring,

Had quite miscarried. I dare be bound again,

My soul upon the forfeit, that your lord

Will never more break faith advisedly.

PORTIA

Then you shall be his surety. Give him this,

And bid him keep it better than the other.

ANTONIO

Here, Lord Bassanio, swear to keep this ring.

BASSANIO

By heaven, it is the same I gave the doctor!

PORTIA

I had it of him. Pardon me, Bassanio,

For by this ring, the doctor lay with me.

NERISSA

And pardon me, my gentle Graziano,

For that same scrubbed boy, the doctor’s clerk,

In lieu of this last night did lie with me.

GRAZIANO

Why, this is like the mending of highways

In summer where the ways are fair enough I

What, are we cuckolds ere we have deserved it?

PORTIA

Speak not so grossly. You are all amazed.

Here is a letter. Read it at your leisure.

It comes from Padua, from Bellario.

There you shall find that Portia was the doctor,

Nerissa there her clerk. Lorenzo here

Shall witness I set forth as soon as you,

And even but now returned. I have not yet

Entered my house. Antonio, you are welcome,

And I have better news in store for you

Than you expect. Unseal this letter soon.

There you shall find three of your argosies

Are richly come to harbour suddenly.

You shall not know by what strange accident

I chanced on this letter.

ANTONIO I am dumb!

BASSANIO (to Portia)

Were you the doctor and I knew you not?

GRAZIANO (to Nerissa)

Were you the clerk that is to make me cuckold?

NERISSA

Ay, but the clerk that never means to do it

Unless he live until he be a man.

BASSANIO (to Portia)

Sweet doctor, you shall be my bedfellow.

When I am absent, then lie with my wife.

ANTONIO (to Portia)

Sweet lady, you have given me life and living,

For here I read for certain that my ships

Are safely come to road.

PORTIA How now, Lorenzo?

My clerk hath some good comforts, too, for you.

NERISSA

Ay, and I’ll give them him without a fee.

There do I give to you and Jessica

From the rich Jew a special deed of gift,

After his death, of all he dies possessed of.

LORENZO

Fair ladies, you drop manna in the way

Of starved people.

PORTIA It is almost morning,

And yet I am sure you are not satisfied

Of these events at full. Let us go in,

And charge us there upon inter’gatories,

And we will answer all things faithfully.

GRAZIANO

Let it be so. The first inter’gatory

That my Nerissa shall be sworn on is

Whether till the next night she had rather stay,

Or go to bed now, being two hours to day.

But were the day come, I should wish it dark

Till I were couching with the doctor’s clerk.

Well, while I live I’ll fear no other thing

So sore as keeping safe Nerissa’s ring. Exeunt

1 HENRY IV

THE play described in the 1623 Folio as The First Part of Henry the Fourth had been entered on the Stationers’ Register on 25 February 1598 as The History of Henry the Fourth, and that is the title of the first surviving edition, of the same year. An earlier edition, doubtless also printed in 1598, is known only from a single, eight-page fragment. Five more editions appeared before the Folio.

The printing of at least two editions within a few months, and the fact that one of them was read almost out of existence, reflect a matter of exceptional topical interest. The earliest title-page advertises the play’s portrayal of ‘the humorous conceits of Sir John Falstaff’; but when it was first acted, probably in 1596 or 1597, this character bore the name of his historical counterpart, the Protestant martyr Sir John Oldcastle. Shakespeare changed his surname as the result of protests from Oldcastle’s descendants, the influential Cobham family, one of whom—William Brooke, 7th Lord Cobham—was Elizabeth I’s Lord Chamberlain from August 1596 till he died on 5 March 1597. Our edition restores Sir John’s original surname for the first time in printed texts (though there is reason to believe that even after the earliest performances the name ’Oldcastle’ was sometimes used on the stage), and also restores Russell and Harvey, names Shakespeare was probably obliged to alter to Bardolph and Peto.

Shakespeare had already shown Henry IV’s rise to power, and his troubled state of mind on achieving it, in Richard II; that play also shows Henry’s dissatisfaction with his wayward son, Prince Harry, later Henry V. 1 Henry IV continues the story, but in a very different dramatic style. A play called The Famous Victories of Henry V, entered in the Stationers’ Register in 1594, was published anonymously, in a debased and shortened text, in 1598. This text—which also features Oldcastle as a reprobate—gives a sketchy version of the events portrayed in 1 and 2 Henry IV and Henry V. Shakespeare must have known the original play, but in the absence of a full text we cannot tell how much he depended on it. The surviving version contains nothing about the rebellions against Henry IV, for which Shakespeare seems to have gone to IIolinshed’s, and perhaps other, Chronicles; he draws also on Samuel Daniel’s poem The First Four Books of the Civil Wars (1595).

1 Henry IV is the first of Shakespeare’s history plays to make extensive use of the techniques of comedy. On a national level, the play shows the continuing problems of Henry Bolingbroke, insecure in his hold on the throne, and the victim of rebellions led by Worcester, Hotspur (Harry Percy), and Glyndwr. These scenes are counterpointed by others, written mainly in prose, which, in the manner of a comic sub-plot, provide humorous diversion while also reflecting and extending the concerns of the main plot. Henry suffers not only public insurrection but the personal rebellion of Prince Harry, in his unprincely exploits with the reprobate old knight, Oldcastle. Sir John has become Shakespeare’s most famous comic character, but Shakespeare shows that the Prince’s treatment of him as a surrogate father who must eventually be abandoned has an intensely serious side.

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

The History of Henry the Fourth

1.1 Enter King Henry, Lord John of Lancaster, and the Earl of Westmorland, with other ⌈lords⌉

KING HENRY

So shaken as we are, so wan with care,

Find we a time for frighted peace to pant

And breathe short-winded accents of new broils

To be commenced in strands afar remote.

No more the thirsty entrance of this soil

Shall daub her lips with her own children’s blood.

No more shall trenching war channel her fields,

Nor bruise her flow‘rets with the armed hoofs

Of hostile paces. Those opposed eyes,

Which, like the meteors of a troubled heaven,

All of one nature, of one substance bred,

Did lately meet in the intestine shock

And furious close of civil butchery,

Shall now in mutual well-beseeming ranks

March all one way, and be no more opposed

Against acquaintance, kindred, and allies.

The edge of war, like an ill-sheathèd knife,

No more shall cut his master. Therefore, friends,

As far as to the sepulchre of Christ—

Whose soldier now, under whose blessèd cross

We are impressèd and engaged to fight—

Forthwith a power of English shall we levy,

Whose arms were moulded in their mothers’ womb

To chase these pagans in those holy fields

Over whose acres walked those blessed feet

Which fourteen hundred years ago were nailed,

For our advantage, on the bitter cross.

But this our purpose now is twelve month old,

And bootless ’tis to tell you we will go.

Therefor we meet not now. Then let me hear

Of you, my gentle cousin Westmorland,

What yesternight our Council did decree

In forwarding this dear expedience.

WESTMORLAND

My liege, this haste was hot in question,

And many limits of the charge set down

But yesternight, when all athwart there came

A post from Wales, loaden with heavy news,

Whose worst was that the noble Mortimer,

Leading the men of Herefordshire to fight

Against the irregular and wild Glyndwr,

Was by the rude hands of that Welshman taken,

A thousand of his people butcherèd,

Upon whose dead corpse’ there was such misuse,

Such beastly shameless transformation,

By those Welshwomen done as may not be

Without much shame retold or spoken of.

KING HENRY

It seems then that the tidings of this broil

Brake off our business for the Holy Land.

WESTMORLAND

This matched with other did, my gracious lord,

For more uneven and unwelcome news

Came from the north, and thus it did import:

On Holy-rood day the gallant Hotspur there—

Young Harry Percy—and brave Archibald,

That ever valiant and approvèd Scot,

At Holmedon met,

Where they did spend a sad and bloody hour,

As by discharge of their artillery

And shape of likelihood the news was told;

For he that brought them in the very heat

And pride of their contention did take horse,

Uncertain of the issue any way.

KING HENRY

Here is a dear, a true industrious friend,

Sir Walter Blunt, new lighted from his horse,

Stained with the variation of each soil

Betwixt that Holmedon and this seat of ours;

And he hath brought us smooth and welcome news.

The Earl of Douglas is discomfited.

Ten thousand bold Scots, two-and-twenty knights,

Balked in their own blood did Sir Walter see

On Holmedon’s plains. Of prisoners Hotspur took

Mordake the Earl of Fife and eldest son

To beaten Douglas, and the Earl of Athol,

Of Moray, Angus, and Menteith;

And is not this an honourable spoil,

A gallant prize? Ha, cousin, is it not?

WESTMORLAND

In faith, it is a conquest for a prince to boast of.

KING HENRY

Yea, there thou mak‘st me sad, and mak’st me sin

In envy that my lord Northumberland

Should be the father to so blest a son—

A son who is the theme of honour’s tongue,

Amongst a grove the very straightest plant,

Who is sweet Fortune’s minion and her pride—

Whilst I by looking on the praise of him

See riot and dishonour stain the brow

Of my young Harry. O, that it could be proved

That some night-tripping fairy had exchanged

In cradle clothes our children where they lay,

And called mine Percy, his Plantagenet!

Then would I have his Harry, and he mine.

But let him from my thoughts. What think you, coz,

Of this young Percy’s pride? The prisoners

Which he in this adventure hath surprised

To his own use he keeps, and sends me word

I shall have none but Mordake Earl of Fife.

WESTMORLAND

This is his uncle’s teaching. This is Worcester,

Malevolent to you in all aspects,

Which makes him prune himself, and bristle up

The crest of youth against your dignity.

KING HENRY

But I have sent for him to answer this;

And for this cause awhile we must neglect

Our holy purpose to Jerusalem.

Cousin, on Wednesday next our Council we

Will hold at Windsor. So inform the lords.

But come yourself with speed to us again,

For more is to be said and to be done

Than out of anger can be uttered.

WESTMORLAND I will, my liege.

Exeunt ⌈King Henry, Lancaster, and other lords at one door; Westmorland at another door⌉