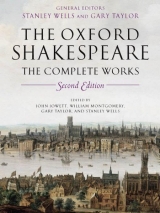

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 32 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

2.1 Enter ⌈on the walls⌉ a French Sergeant of a band, with two Sentinels

SERGEANT

Sirs, take your places and be vigilant.

If any noise or soldier you perceive

Near to the walls, by some apparent sign

Let us have knowledge at the court of guard.

⌈A SENTINEL⌉

Sergeant, you shall. Exit Sergeant Thus are poor servitors,

When others sleep upon their quiet beds,

Constrained to watch in darkness, rain, and cold.

Enter Lord Talbot, the Dukes of Bedford and Burgundy, and soldiers with scaling ladders, their drums beating a dead march

TALBOT

Lord regent, and redoubted Burgundy—

By whose approach the regions of Artois,

Wallon, and Picardy are friends to us—

This happy night the Frenchmen are secure,

Having all day caroused and banqueted.

Embrace we then this opportunity,

As fitting best to quittance their deceit,

Contrived by art and baleful sorcery.

BEDFORD

Coward of France! How much he wrongs his fame,

Despairing of his own arms’ fortitude,

To join with witches and the help of hell.

BURGUNDY

Traitors have never other company.

But what’s that ‘Pucelle’ whom they term so pure?

TALBOT

A maid, they say.

BEDFORD A maid? And be so martial?

BURGUNDY

Pray God she prove not masculine ere long.

If underneath the standard of the French

She carry armour as she hath begun—

TALBOT

Well, let them practise and converse with spirits.

God is our fortress, in whose conquering name

Let us resolve to scale their flinty bulwarks.

BEDFORD

Ascend, brave Talbot. We will follow thee.

TALBOT

Not all together. Better far, I guess,

That we do make our entrance several ways—

That, if it chance the one of us do fail,

The other yet may rise against their force.

BEDFORD

Agreed. I’ll to yon corner.

BURGUNDY And I to this.

⌈Exeunt severally Bedford and Burgundy with some soldiers⌉

TALBOT

And here will Talbot mount, or make his grave.

Now, Salisbury, for thee, and for the right

Of English Henry, shall this night appear

How much in duty I am bound to both.

⌈Talbot and his soldiers⌉ scale the walls

⌈SENTINELS⌉

Arm! Arm! The enemy doth make assault!

ENGLISH SOLDIERS Saint George! A Talbot! Exeunt above

⌈Alarum.⌉ The French ⌈soldiers⌉ leap o’er the walls in their shirts ⌈and exeunt⌉. Enter several ways the Bastard of Orléans, the Duke of Alençon, and René Duke of Anjou, half ready and half unready

ALENÇON

How now, my lords? What, all unready so?

BASTARD

Unready? Ay, and glad we scaped so well.

RENÉ

‘Twas time, I trow, to wake and leave our beds,

Hearing alarums at our chamber doors.

ALENÇON

Of all exploits since first I followed arms

Ne’er heard I of a warlike enterprise

More venturous or desperate than this.

BASTARD

I think this Talbot be a fiend of hell.

RENÉ

If not of hell, the heavens sure favour him.

ALENÇON

Here cometh Charles. I marvel how he sped.

Enter Charles the Dauphin and Joan la Pucelle

BASTARD

Tut, holy Joan was his defensive guard.

CHARLES (to Joan)

Is this thy cunning, thou deceitful dame?

Didst thou at first, to flatter us withal,

Make us partakers of a little gain

That now our loss might be ten times so much?

JOAN

Wherefore is Charles impatient with his friend?

At all times will you have my power alike?

Sleeping or waking must I still prevail,

Or will you blame and lay the fault on me?—

Improvident soldiers, had your watch been good,

This sudden mischief never could have fall’n.

CHARLES

Duke of Alençon, this was your default,

That, being captain of the watch tonight,

Did look no better to that weighty charge.

ALENÇON

Had all your quarters been as safely kept

As that whereof I had the government,

We had not been thus shamefully surprised.

BASTARD

Mine was secure.

RENÉ And so was mine, my lord.

CHARLES

And for myself, most part of all this night

Within her quarter and mine own precinct

I was employed in passing to and fro

About relieving of the sentinels.

Then how or which way should they first break in?

JOAN

Question, my lords, no further of the case,

How or which way. ‘Tis sure they found some place

But weakly guarded, where the breach was made.

And now there rests no other shift but this—

To gather our soldiers, scattered and dispersed,

And lay new platforms to endamage them.

Alarum. Enter an English Soldier

ENGLISH SOLDIER A Talbot! A Talbot!

The French fly, leaving their clothes behind

ENGLISH SOLDIER

I’ll be so bold to take what they have left.

The cry of ‘Talbot’ serves me for a sword,

For I have loaden me with many spoils,

Using no other weapon but his name. Exit with spoils

2.2 Enter Lord Talbot, the Dukes of Bedford and Burgundy, a Captain, ⌈and soldiers⌉

BEDFORD

The day begins to break and night is fled,

Whose pitchy mantle overveiled the earth.

Here sound retreat and cease our hot pursuit.

Retreat is sounded

TALBOT

Bring forth the body of old Salisbury

And here advance it in the market place,

The middle centre of this cursed town.

⌈Exit one or more⌉

Now have I paid my vow unto his soul:

For every drop of blood was drawn from him

There hath at least five Frenchmen died tonight.

And that hereafter ages may behold

What ruin happened in revenge of him,

Within their chiefest temple I’ll erect

A tomb, wherein his corpse shall be interred—

Upon the which, that everyone may read,

Shall be engraved the sack of Orléans,

The treacherous manner of his mournful death,

And what a terror he had been to France.

But, lords, in all our bloody massacre

I muse we met not with the Dauphin’s grace,

His new-come champion, virtuous Joan of Arc,

Nor any of his false confederates.

BEDFORD

‘Tis thought, Lord Talbot, when the fight began,

Roused on the sudden from their drowsy beds,

They did amongst the troops of armed men

Leap o’er the walls for refuge in the field.

BURGUNDY

Myself, as far as I could well discern

For smoke and dusky vapours of the night,

Am sure I scared the Dauphin and his trull,

When arm-in-arm they both came swiftly running,

Like to a pair of loving turtle-doves

That could not live asunder day or night.

After that things are set in order here,

We’ll follow them with all the power we have.

Enter a Messenger

MESSENGER

All hail, my lords! Which of this princely train

Call ye the warlike Talbot, for his acts

So much applauded through the realm of France?

TALBOT

Here is the Talbot. Who would speak with him?

MESSENGER

The virtuous lady, Countess of Auvergne,

With modesty admiring thy renown,

By me entreats, great lord, thou wouldst vouchsafe

To visit her poor castle where she lies,

That she may boast she hath beheld the man

Whose glory fills the world with loud report.

BURGUNDY

Is it even so? Nay, then I see our wars

Will turn unto a peaceful comic sport,

When ladies crave to be encountered with.

You may not, my lord, despise her gentle suit.

TALBOT

Ne’er trust me then, for when a world of men

Could not prevail with all their oratory,

Yet hath a woman’s kindness overruled.—

And therefore tell her I return great thanks,

And in submission will attend on her.—

Will not your honours bear me company?

BEDFORD

No, truly, ‘tis more than manners will.

And I have heard it said, ‘Unbidden guests

Are often welcomest when they are gone’.

TALBOT

Well then, atone—since there’s no remedy—

I mean to prove this lady’s courtesy.

Come hither, captain.

He whispers

You perceive my mind?

CAPTAIN

I do, my lord, and mean accordingly.

Exeunt ⌈severally⌉

2.3 Enter the Countess of Auvergne and her Porter

COUNTESS

Porter, remember what I gave in charge,

And when you have done so, bring the keys to me.

PORTER Madam, I will. Exit

COUNTESS

The plot is laid. If all things fall out right,

I shall as famous be by this exploit

As Scythian Tomyris by Cyrus’ death.

Great is the rumour of this dreadful knight,

And his achievements of no less account.

Fain would mine eyes be witness with mine ears,

To give their censure of these rare reports.

Enter Messenger and Lord Talbot

MESSENGER

Madam, according as your ladyship desired,

By message craved, so is Lord Talbot come.

COUNTESS

And he is welcome. What, is this the man?

MESSENGER

Madam, it is.

COUNTESS Is this the scourge of France?

Is this the Talbot, so much feared abroad

That with his name the mothers still their babes?

I see report is fabulous and false.

I thought I should have seen some Hercules,

A second Hector, for his grim aspect

And large proportion of his strong-knit limbs.

Alas, this is a child, a seely dwarf.

It cannot be this weak and writhled shrimp

Should strike such terror to his enemies.

TALBOT

Madam, I have been bold to trouble you.

But since your ladyship is not at leisure,

I’ll sort some other time to visit you.

He is going

COUNTESS (to Messenger)

What means he now? Go ask him whither he goes.

MESSENGER

Stay, my Lord Talbot, for my lady craves

To know the cause of your abrupt departure.

TALBOT

Marry, for that she’s in a wrong belief,

I go to certify her Talbot’s here.

Enter Porter with keys

COUNTESS

If thou be he, then art thou prisoner.

TALBOT

Prisoner? To whom?

COUNTESS To me, bloodthirsty lord;

And for that cause I trained thee to my house.

Long time thy shadow hath been thrall to me,

For in my gallery thy picture hangs;

But now the substance shall endure the like,

And I will chain these legs and arms of thine

That hast by tyranny these many years

Wasted our country, slain our citizens,

And sent our sons and husbands captivate—

TALBOT Ha, ha, ha!

COUNTESS

Laughest thou, wretch? Thy mirth shall turn to moan.

TALBOT

I laugh to see your ladyship so fond

To think that you have aught but Talbot’s shadow

Whereon to practise your severity.

COUNTESS Why? Art not thou the man?

TALBOT I am indeed.

COUNTESS Then have I substance too.

TALBOT

No, no, I am but shadow of myself.

You are deceived; my substance is not here.

For what you see is but the smallest part

And least proportion of humanity.

I tell you, madam, were the whole frame here,

It is of such a spacious lofty pitch

Your roof were not sufficient to contain’t.

COUNTESS

This is a riddling merchant for the nonce.

He will be here, and yet he is not here.

How can these contrarieties agree?

TALBOT

That will I show you presently.

He winds his horn. Within, drums strike up; a peal of ordnance. Enter English soldiers

How say you, madam? Are you now persuaded

That Talbot is but shadow of himself?

These are his substance, sinews, arms, and strength,

With which he yoketh your rebellious necks,

Razeth your cities and subverts your towns,

And in a moment makes them desolate.

COUNTESS

Victorious Talbot, pardon my abuse.

I find thou art no less than fame hath bruited,

And more than may be gathered by thy shape.

Let my presumption not provoke thy wrath,

For I am sorry that with reverence

I did not entertain thee as thou art.

TALBOT

Be not dismayed, fair lady, nor misconster

The mind of Talbot, as you did mistake

The outward composition of his body.

What you have done hath not offended me;

Nor other satisfaction do I crave

But only, with your patience, that we may

Taste of your wine and see what cates you have:

For soldiers’ stomachs always serve them well.

COUNTESS

With all my heart; and think me honoured

To feast so great a warrior in my house. Exeunt

2.4 A rose brier. Enter Richard Plantagenet, the Earl of Warwick, the Duke of Somerset, William de la Pole (the Earl of Suffolk), Vernon, and a Lawyer

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Great lords and gentlemen, what means this silence?

Dare no man answer in a case of truth?

SUFFOLK

Within the Temple hall we were too loud.

The garden here is more convenient.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Then say at once if I maintained the truth;

Or else was wrangling Somerset in th’error?

SUFFOLK

Faith, I have been a truant in the law,

And never yet could frame my will to it,

And therefore frame the law unto my will.

SOMERSET

Judge you, my lord of Warwick, then between us.

WARWICK

Between two hawks, which flies the higher pitch,

Between two dogs, which hath the deeper mouth,

Between two blades, which bears the better temper,

Between two horses, which doth bear him best,

Between two girls, which hath the merriest eye,

I have perhaps some shallow spirit of judgement;

But in these nice sharp quillets of the law,

Good faith, I am no wiser than a daw.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Tut, tut, here is a mannerly forbearance.

The truth appears so naked on my side

That any purblind eye may find it out.

SOMERSET

And on my side it is so well apparelled,

So clear, so shining, and so evident,

That it will glimmer through a blind man’s eye.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Since you are tongue-tied and so loath to speak,

In dumb significants proclaim your thoughts.

Let him that is a true-born gentleman

And stands upon the honour of his birth,

If he suppose that I have pleaded truth,

From off this briar pluck a white rose with me.

He plucks a white rose

SOMERSET

Let him that is no coward nor no flatterer,

But dare maintain the party of the truth,

Pluck a red rose from off this thorn with me.

He plucks a red rose

WARWICK

I love no colours, and without all colour

Of base insinuating flattery

I pluck this white rose with Plantagenet.

SUFFOLK

I pluck this red rose with young Somerset,

And say withal I think he held the right.

VERNON

Stay, lords and gentlemen, and pluck no more

Till you conclude that he upon whose side

The fewest roses from the tree are cropped

Shall yield the other in the right opinion.

SOMERSET

Good Master Vernon, it is well objected.

If I have fewest, I subscribe in silence.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET And I.

VERNON

Then for the truth and plainness of the case

I pluck this pale and maiden blossom here,

Giving my verdict on the white rose’ side.

SOMERSET

Prick not your finger as you pluck it off,

Lest, bleeding, you do paint the white rose red,

And fall on my side so against your will.

VERNON

If I, my lord, for my opinion bleed,

Opinion shall be surgeon to my hurt

And keep me on the side where still I am.

SOMERSET Well, well, come on! Who else?

LAWYER

Unless my study and my books be false,

The argument you held was wrong in law;

In sign whereof I pluck a white rose too.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Now Somerset, where is your argument?

SOMERSET

Here in my scabbard, meditating that

Shall dye your white rose in a bloody red.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Meantime your cheeks do counterfeit our roses,

For pale they look with fear, as witnessing

The truth on our side.

SOMERSET No, Plantagenet,

‘Tis not for fear, but anger, that thy cheeks

Blush for pure shame to counterfeit our roses,

And yet thy tongue will not confess thy error.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Hath not thy rose a canker, Somerset?

SOMERSET

Hath not thy rose a thorn, Plantagenet?

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Ay, sharp and piercing, to maintain his truth,

Whiles thy consuming canker eats his falsehood.

SOMERSET

Well, I’ll find friends to wear my bleeding roses,

That shall maintain what I have said is true,

Where false Plantagenet dare not be seen.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Now, by this maiden blossom in my hand,

I scorn thee and thy fashion, peevish boy.

SUFFOLK

Turn not thy scorns this way, Plantagenet.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Proud Pole, I will, and scorn both him and thee.

SUFFOLK

I’ll turn my part thereof into thy throat.

SOMERSET

Away, away, good William de la Pole.

We grace the yeoman by conversing with him.

WARWICK

Now, by God’s will, thou wrong’st him, Somerset.

His grandfather was Lionel Duke of Clarence,

Third son to the third Edward, King of England.

Spring crestless yeomen from so deep a root?

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

He bears him on the place’s privilege,

Or durst not for his craven heart say thus.

SOMERSET

By him that made me, I’ll maintain my words

On any plot of ground in Christendom.

Was not thy father, Richard Earl of Cambridge,

For treason executed in our late king’s days?

And by his treason stand’st not thou attainted,

Corrupted, and exempt from ancient gentry?

His trespass yet lives guilty in thy blood,

And till thou be restored thou art a yeoman.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

My father was attached, not attainted;

Condemned to die for treason, but no traitor—

And that I’ll prove on better men than Somerset,

Were growing time once ripened to my will.

For your partaker Pole, and you yourself,

I’ll note you in my book of memory,

To scourge you for this apprehension.

Look to it well, and say you are well warned.

SOMERSET

Ah, thou shalt find us ready for thee still,

And know us by these colours for thy foes,

For these my friends, in spite of thee, shall wear.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

And, by my soul, this pale and angry rose,

As cognizance of my blood-drinking hate,

Will I forever, and my faction, wear

Until it wither with me to my grave,

Or flourish to the height of my degree.

SUFFOLK

Go forward, and be choked with thy ambition.

And so farewell until I meet thee next. Exit

SOMERSET

Have with thee, Pole.—Farewell, ambitious Richard.

Exit

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

How I am braved, and must perforce endure it!

WARWICK

This blot that they object against your house

Shall be wiped out in the next parliament,

Called for the truce of Winchester and Gloucester.

An if thou be not then created York,

I will not live to be accounted Warwick.

Meantime, in signal of my love to thee.

Against proud Somerset and William Pole,

Will I upon thy party wear this rose.

And here I prophesy: this brawl today,

Grown to this faction in the Temple garden,

Shall send, between the red rose and the white,

A thousand souls to death and deadly night.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Good Master Vernon, I am bound to you,

That you on my behalf would pluck a flower.

VERNON

In your behalf still will I wear the same.

LAWYER And so will I.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET Thanks, gentles.

Come, let us four to dinner. I dare say

This quarrel will drink blood another day.

Exeunt. The rose brier is removed

2.5 Enter Edmund Mortimer, brought in a chair ⌈by⌉ his Keepers

MORTIMER

Kind keepers of my weak decaying age,

Let dying Mortimer here rest himself.

Even like a man new-haled from the rack,

So fare my limbs with long imprisonment;

And these grey locks, the pursuivants of death,

Argue the end of Edmund Mortimer,

Nestor-like aged in an age of care.

These eyes, like lamps whose wasting oil is spent,

Wax dim, as drawing to their exigent;

Weak shoulders, overborne with burdening grief,

And pithless arms, like to a withered vine

That droops his sapless branches to the ground.

Yet are these feet—whose strengthless stay is numb,

Unable to support this lump of clay—

Swift-winged with desire to get a grave,

As witting I no other comfort have.

But tell me, keeper, will my nephew come?

KEEPER

Richard Plantagenet, my lord, will come.

We sent unto the Temple, unto his chamber,

And answer was returned that he will come.

MORTIMER

Enough. My soul shall then be satisfied.

Poor gentleman, his wrong doth equal mine.

Since Henry Monmouth first began to reign—

Before whose glory I was great in arms—

This loathsome sequestration have I had;

And even since then hath Richard been obscured,

Deprived of honour and inheritance.

But now the arbitrator of despairs,

Just Death, kind umpire of men’s miseries,

With sweet enlargement doth dismiss me hence.

I would his troubles likewise were expired,

That so he might recover what was lost.

Enter Richard Plantagenet

KEEPER

My lord, your loving nephew now is come.

MORTIMER

Richard Plantagenet, my friend, is he come?

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Ay, noble uncle, thus ignobly used:

Your nephew, late despised Richard, comes.

MORTIMER (to Keepers)

Direct mine arms I may embrace his neck

And in his bosom spend my latter gasp.

O tell me when my lips do touch his cheeks,

That I may kindly give one fainting kiss.

He embraces Richard

And now declare, sweet stem from York’s great stock,

Why didst thou say of late thou wert despised?

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

First lean thine aged back against mine arm,

And in that ease I’ll tell thee my dis-ease.

This day in argument upon a case

Some words there grew ’twixt Somerset and me;

Among which terms he used his lavish tongue

And did upbraid me with my father’s death;

Which obloquy set bars before my tongue,

Else with the like I had requited him.

Therefore, good uncle, for my father’s sake,

In honour of a true Plantagenet,

And for alliance’ sake, declare the cause

My father, Earl of Cambridge, lost his head.

MORTIMER

That cause, fair nephew, that imprisoned me,

And hath detained me all my flow’ring youth

Within a loathsome dungeon, there to pine,

Was cursed instrument of his decease.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Discover more at large what cause that was,

For I am ignorant and cannot guess.

MORTIMER

I will, if that my fading breath permit

And death approach not ere my tale be done.

Henry the Fourth, grandfather to this King,

Deposed his nephew Richard, Edward’s son,

The first begotten and the lawful heir

Of Edward king, the third of that descent;

During whose reign the Percies of the north,

Finding his usurpation most unjust,

Endeavoured my advancement to the throne.

The reason moved these warlike lords to this

Was for that—young King Richard thus removed,

Leaving no heir begotten of his body—

I was the next by birth and parentage,

For by my mother I derived am

From Lionel Duke of Clarence, the third son

To King Edward the Third—whereas the King

From John of Gaunt doth bring his pedigree,

Being but fourth of that heroic line.

But mark: as in this haughty great attempt

They laboured to plant the rightful heir,

I lost my liberty, and they their lives.

Long after this, when Henry the Fifth,

Succeeding his father Bolingbroke, did reign,

Thy father, Earl of Cambridge then, derived

From famous Edmund Langley, Duke of York,

Marrying my sister that thy mother was,

Again, in pity of my hard distress,

Levied an army, weening to redeem

And have installed me in the diadem;

But, as the rest, so fell that noble earl,

And was beheaded. Thus the Mortimers,

In whom the title rested, were suppressed.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Of which, my lord, your honour is the last.

MORTIMER

True, and thou seest that I no issue have,

And that my fainting words do warrant death.

Thou art my heir. The rest I wish thee gather—

But yet be wary in thy studious care.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

Thy grave admonishments prevail with me.

But yet methinks my father’s execution

Was nothing less than bloody tyranny.

MORTIMER

With silence, nephew, be thou politic.

Strong-fixed is the house of Lancaster,

And like a mountain, not to be removed.

But now thy uncle is removing hence,

As princes do their courts, when they are cloyed

With long continuance in a settled place.

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

O uncle, would some part of my young years

Might but redeem the passage of your age.

MORTIMER

Thou dost then wrong me, as that slaughterer doth

Which giveth many wounds when one will kill.

Mourn not, except thou sorrow for my good.

Only give order for my funeral.

And so farewell, and fair be all thy hopes,

And prosperous be thy life in peace and war. Dies

RICHARD PLANTAGENET

And peace, no war, befall thy parting soul.

In prison hast thou spent a pilgrimage,

And like a hermit overpassed thy days.

Well, I will lock his counsel in my breast,

And what I do imagine, let that rest.

Keepers, convey him hence, and I myself

Will see his burial better than his life.

Exeunt Keepers with Mortimer’s body

Here dies the dusky torch of Mortimer,

Choked with ambition of the meaner sort.

And for those wrongs, those bitter injuries,

Which Somerset hath offered to my house,

I doubt not but with honour to redress.

And therefore haste I to the Parliament,

Either to be restored to my blood,

Or make mine ill th’advantage of my good. Exit