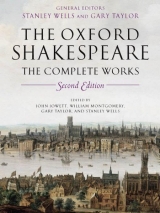

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

Vocabulary

Vocabulary is the area of language least subject to generalization. Unlike the grammar, prosody, and discourse patterns of a language, which are subject to general rules that can be learned thoroughly in a relatively short period of time, the learning of vocabulary is largely ad hoc and of indefinite duration. By contrast with the few hundred points of pronunciation, grammar, and discourse structure which we need to consider when dealing with Shakespeare’s language, the number of points of vocabulary run into several thousands. As a result, most books do little more than provide an alphabetical glossary of the items which pose a difficulty of comprehension.

The question of the size of Shakespeare’s vocabulary, and its impact on the development of the English language, has always captured popular imagination, but at the cost of distracting readers from more important aspects of his lexical creativity. It is never the number of words that makes an author, but how those words are used. Because of Shakespeare’s literary and dramatic brilliance, it is usually assumed that his vocabulary must have been vast, and that his lexical innovations had a major and permanent effect on the language. In fact, it transpires that the number of words in his lexicon (ignoring variations of the kind described below) was somewhere between 17,000 and 20,000-quite small by present-day standards, though probably much larger than his contemporaries. And the number of his lexical innovations, insofar as these can be identified reliably, are probably no more than 1,700, less than half of which have remained in the language. No other author matches these impressive figures, but they nonetheless provide only a small element of the overall size of the English lexicon, which even in Early Modern English times was around 150,000.

The uncertainty in the personal total arises because it is not easy to say what should be counted. Much depends on the selection of texts and the amount of text recognized (as the present edition illustrates with King Lear and Hamlet), as well as on editorial policy towards such matters as hyphenation. In Kent’s harangue of Oswald (The Tragedy of King Lear), for example, the number of words varies depending on which compounds the editors recognize. In this extract (2.2.13-17), The Complete Works identifies 20; by comparison, the First Folio shows 22:

Complete Works: a base, proud, shallow, beggarly, three-suited, hundred-pound, filthy worsted-stocking knave; a lily-livered, action-taking, whoreson, glass-gazing, super-serviceable, finical rogue; one-trunk-inheriting slave . . .

First Folio: a base, proud, shallow, beggerly, three-suited-hundred pound, filthy woosted stocking knaue, a Lilly-liuered, action-taking, whoreson, glasse-gazing super-seruiceable finicall Rogue, one Trunke-inheriting slaue ...

Other editions reach different totals: one allows a three-element compound word (filthy-worsted-stocking, Penguin); another a four-element (three-suited-hundred-pound, Arden).

The number of words in a person’s lexicon refers to the items which would appear as headwords in a dictionary, once grammatical, metrical, and orthographic variations are discounted. For example, in the First Folio we find the following forms: take, takes, taketh, taking, tak‘n, taken, tak’st, tak’t, took, took’st, tooke, tookst. It would be absurd to think of these as ‘twelve words’ showing us twelve aspects of Shakespeare’s lexical creativity. They are simply twelve forms of the same word, ‘take’. And there are several other types of word which we would want to exclude when deciding on the size of Shakespeare’s vocabulary. It is usual to exclude proper names from a count (Benvolio, Eastcheap), unless they have a more general significance (Ethiop). People usually exclude the foreign words (from Latin, French, etc.), though there are problems in deciding what to do with the franglais used in Henry V. Word counters wonder what to do, also, with onomatopoeic words (e.g. sa, sese) and humorous forms: should we count malapropisms separately or as variants of their supposed targets (e.g. allicholly as a variant of melancholy)? If we include everything, we shall approach 20,000; if we do not, we shall look for the lower figure, around 17,000.

How many of these words have gone out of use or changed their meaning between Early Modern English and today? A recent glossary which aims at comprehensiveness, Shakespeare’s Words (Crystal and Crystal, 2002), contains 13,626 headwords which fall into this category – roughly three-quarters of Shakespeare’s total word-stock. But this does not mean that three-quarters of the words in The Complete Works represent Early Modern English, for many of these older words are used only once or twice in the canon. If we perform an alternative calculation – not the number of different words (the word types), but the number of instances of each word (the word tokens), we end up with a rather different figure. According to Marvin Spevack’s concordance, there are nearly 885,000 word tokens in the canon – and this total would increase to over 900,000 with the addition of The Two Noble Kinsmen. The 13,626 word types in the glossary are actually represented by some 50,000 word tokens – and 50,000 is only 5 per cent of 900,000. This is why the likelihood of encountering an Early Modern English word in reading a play or a poem is actually quite small. Most of the words in use then are still in use today, with no change in meaning.

The attention of glossary-writers and text editors has always focused on the ‘different words’, but it is important to note that they do not all pose the same kind of difficulty. At one extreme, there are many words which hardly need any gloss at all:

• words such as oft, perchance, sup, morrow, visage, pate, knave, wench, and morn, which are still used today in special contexts, such as poetry or comic archaism, or which still have some regional use (e.g. aye ‘always’);

• words where a difference has arisen solely because of the demands of the metre, such as vasty instead of vast (‘The vasty fields of France’, Henry V, Prologue 12), and other such uses of the -y suffix, such as steepy and plumpy;

• words where the formal difference is too small to obscure the meaning, such as affright (‘frighten’), afeard (‘afraid’), scape (‘escape’), ope (‘open’), down-trod (‘down-trodden’), and dog-weary (‘dog-tired’);

• words whose elements are familiar but the combination is not, such as bedazzle, dismasked, unpeople, rareness, and smilingly, and such phrasal verbs as press down (‘overburden’), speak with (‘speak to’), and shove by (‘push aside’);

• idioms and compounds whose meaning is transparent, such as what cheer?, go your ways, high-minded, and folly-fallen.

We might also include in this category most of the cases of conversion – where a word belonging to one part of speech is used as a different part of speech. Most often, a common noun is used as a verb, as in ‘grace me no grace, nor uncle me no uncle’ (Richard II, 2.3.86), but there are several other possibilities, which Shakespeare exploits so much that lexical conversion has become one of the trademarks of his style:

She Phoebes me

(As You Like It, 4.3.40)

Thou losest here, a better where to find

(The Tragedy of King Lear, 1.1.261)

they . . . from their own misdeeds askance their eyes

(Lucrece, 1. 636-7)

what man Thirds his own worth

(The Two Noble Kinsmen, 1.2.95-6)

In such cases, although the grammar is strikingly different, the lexical meaning is not.

At the other extreme, there are words where it is not possible to deduce from their form what they might mean – such as finical, fardel, grece, and incony. There are around a thousand such items in Shakespeare, and in these cases we have no alternative but to learn them as we would new words in a foreign language. An alphabetical glossary of synonyms is not the best way of carrying out this task, however, as that arrangement does not display the words in context, and its A-to-Z structure does not allow the reader to develop a sense of the semantic interrelationships involved. It is essential to see the words in their semantic context, for this can help comprehension in a number of ways. Shakespeare sometimes provides the help himself. In Othello, when the Duke says to Brabanzio (1.3.198-200):

Let me speak like yourself, and lay a sentence

Which, as a grece or step, may help these lovers

Into your favour

we can guess what grece means (‘step, degree’) by relying on the following noun. And in Twelfth Night, when Sir Toby says to Maria: ‘Shall I play my freedom at tray-trip, and become thy bondslave?’ (2.5.183-4), we may have no idea what tray-trip is, but the linguistic association (or collocation) with play shows that it must be some kind of game. Collocations always provide major clues to meaning.

An A-to-Z approach provides no clues about the meaning relationships between words: aunt is at one end of the alphabet and uncle at the other. A more beneficial approach to Shakespearian vocabulary is to learn the new words in the way that young children do when they acquire a language. Words are never learned randomly, or alphabetically, but always in context and in pairs or small groups. In this way, meanings reinforce and illuminate each other, in such ways as the following:

• words of opposite meaning (antonyms): best/meanest, mine/countermine, ayward/ nayward, curbed/uncurbed;

• words of included meaning (hyponyms), expressing the notion that ‘an X is a kind of Y’: bass viol—viol, boot-hose-hose; mortar-piece/murdering-pjece—piece; grave-/well-/ ill-beseeming—beseeming; half-blown/unblown—blown;

• words of the same or very similar meaning (synonyms): advantage/vantage, argal/argo, compter/counter, coz/cousin (these words sometimes convey a stylistic contrast, such as informal vs. formal);

• words of intensifying meaning: lusty/over-lusty, pleachedlthick-pleached, force/force perforce, rash/heady-rash, amazed/all-amazed.

In many cases, it is sensible to group words into semantic fields, such as ‘clothing’, ‘weapons’, or ‘money’, so that we can more clearly see the relationships between them. Under the last heading, for example, we can distinguish between domestic coins (such as pennies) and foreign coins (such as ducats), and within the former to relate items in terms of their increasing value: obolus, halfpence, three farthings, penny, twopence, threepence, groat, sixpence, tester/testril, shilling, noble, angel, royal, pound. That is how we learn a monetary system today, and it is how we can approach the one we find in Shakespeare.

In between the extremes of lexical familiarity and unfamiliarity, we find the majority of Shakespeare’s difficult words – difficult not because they are different in form from the vocabulary we know today but because they have changed their meaning. In many cases, the meaning change is very slight (intent ‘intention’; glass ‘looking-glass’) or has little consequence. When Jack Cade says ‘I have eat no meat these five days, yet come thou and thy five men, an if I do not leave you all as dead as a doornail I pray God I may never eat grass more’ (Contention, 4.9.37-40), meat is here being used in the general sense of ‘food’ – but if we were to interpret it in the modern, restricted sense of ‘flesh meat’, the effect would not be greatly different. By contrast, there are several hundred cases where the meaning has changed so much that it would be highly misleading to read in the modern sense. These are the ‘false friends’ (faux amis) of comparative semantics – words in a language which seem familiar but are not (as between French and English, where demander means ‘ask’, and demand is translated by requérir). False friends in Shakespeare include naughty (‘wicked’), heavy (‘sorrowful’), humorous (‘moody’), sad (‘serious’), ecstasy (‘madness’), owe (‘own’), merely (‘totally’), and envious (‘malicious’). In such cases, we need to pay careful attention to the context, which we must always allow to overrule the intrusion of the irrelevant modern meaning. We can see this operating, for example, in The Tragedy of King Lear (5.1.5-7):

REGAN

Our sister’s man is certainly miscarried.

EDMOND

‘Tis to be doubted, madam.

REGAN

Now, sweet lord, You know the goodness I intend upon you.

If we were to read in the modern meaning of doubt, it would suggest that Edmond is disagreeing with Regan – but as the context suggests this is not the case, we need a different meaning of doubt - ‘fear’.

Finally, as with grammar, we must be prepared to see the demands of metre altering word forms. The choice between vantage and advantage, scape and escape, shrew and beshrew and many other such alternatives can be solely due to the location of the word in the line. Sometimes we can even see the alternative forms juxtaposed, as when both oft and often appear in Julius Caesar (3.1.115-19):

BRUTUS

How many times shall Caesar bleed in sport,

That now on Pompey’s basis lies along,

No worthier than the dust!

CASSIUS

So oft as that shall be,

So often shall the knot of us be called

The men that gave their country liberty.

Names can be altered too. At one point in Pericles, narrator Gower refers to Pericles’ counsellor with his full name:

In Helicanus may you well descry

A figure of truth.

(22.114-15)

At another, he shortens it:

Good Helicane that stayed at home,

Not to eat honey like a drone.

(5.17-18)

Such metrically induced alternations rarely have any semantic or pragmatic consequence.

The examples in this essay show that in order to develop our understanding of Shakespeare’s use of language we need to work through a three-stage process:

• we first notice a linguistic feature – something which strikes us as particularly interesting, effective, unusual, or problematic (often because it differs from what we would expect in Modern English);

• we then have to describe the feature, in order to talk about it and to classify it as a feature of a particular type; the more precisely we are able to do this, by developing an awarenesss of phonetic, grammatical, and other terminology, the more we will be able to reach clear and statable conclusions;

• we have to explain why the feature is there.

It is the last stage which is the most important, and which is still surprisingly neglected. It is never enough, as has often happened in approaches to Shakespeare’s language, simply to identify and describe an interesting feature – such as a particular metrical pattern, piece of alliteration, word order, or literary allusion – and proceed no further. We must also try to explain its role – its meaning and effect – in the context in which it appears, and that is why this essay has paid so much attention to seeing his language within a semantic and pragmatic perspective.

It is, of course, by no means the whole story. Language in turn must be placed within a wider literary, dramatic, historical, psychological, and social frame of reference. We must also expect there to be many occasions when meaning and effect cannot be precisely determined. There will always be a range of interpretive possibilities in the language that offer the individual reader, actor, director, or playgoer a personal choice. But the linguistic stage in our study of Shakespeare should never be minimized or neglected, for it is an essential step in increasing our insight into his dramatic and poetic artistry.

CONTEMPORARY ALLUSIONS TO SHAKESPEARE

MANY contemporary documents, some manuscript, some printed, refer directly to Shakespeare and to members of his family. The following list (which is not exhaustive) briefly indicates the nature of the principal allusions to him and to his closest relatives. It does not include publication records of his plays (given in the Textual Companion), the appearances of his name on title-pages, unascribed allusions to his works, commendatory poems, epistles, and dedications printed elsewhere in the edition, or records of performances except for that of 1604-5, in which Shakespeare is named. The principal documents are discussed, and most of them reproduced, in S. Schoenbaum’s William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life (1975).

COMMENDATORY POEMS AND PREFACES (1599-1640)

Ad Gulielmum Shakespeare

Honey-tongued Shakespeare, when I saw thine issue

I swore Apollo got them, and none other,

Their rosy-tainted features clothed in tissue,

Some heaven-born goddess said to be their mother.

Rose-cheeked Adonis with his amber tresses,

Fair fire-hot Venus charming him to love her,

Chaste Lucretia virgin-like her dresses,

Proud lust-stung Tarquin seeking still to prove her,

Romeo, Richard, more whose names I know not—

Their sugared tongues and power-attractive beauty

Say they are saints although that saints they show not,

For thousands vows to them subjective duty.

They burn in love, thy children; Shakespeare het them;

Go, woo thy muse more nymphish brood beget them.

John Weever, Epigrams (1599)

A never writer to an ever reader: news

Eternal reader, you have here a new play never staled with the stage, never clapper-clawed with the palms of the vulgar, and yet passing full of the palm comical, for it is a birth of that brain that never undertook anything comical vainly; and were but the vain names of comedies changed for the titles of commodities, or of plays for pleas, you should see all those grand censors that now style them such vanities flock to them for the main grace of their gravities, especially this author’s comedies, that are so framed to the life that they serve for the most common commentaries of all the actions of our lives, showing such a dexterity and power of wit that the most displeased with plays are pleased with his comedies, and all such dull and heavy-witted worldlings as were never capable of the wit of a comedy, coming by report of them to his representations, have found that wit there that they never found in themselves, and have parted better witted than they came, feeling an edge of wit set upon them more than ever they dreamed they had brain to grind it on. So much and such savoured salt of wit is in his comedies that they seem, for their height of pleasure, to be born in that sea that brought forth Venus. Amongst all there is none more witty than this, and had I time I would comment upon it, though I know it needs not for so much as will make you think your testern well bestowed, but for so much worth as even poor I know to be stuffed in it. It deserves such a labour as well as the best comedy in Terence or Plautus. And believe this, that when he is gone and his comedies out of sale, you will scramble for them, and set up a new English Inquisition. Take this for a warning, and at the peril of your pleasure’s loss and judgement’s, refuse not, nor like this the less for not being sullied with the smoky breath of the multitude; but thank fortune for the scape it hath made amongst you, since by the grand possessors’ wills I believe you should have prayed for them rather than been prayed. And so I leave all such to be prayed for, for the states of their wits’ healths, that will not praise it.

Vale.

Anonymous, in Troilus and Cressida (1609)

To our English Terence, Master Will Shakespeare

Some say, good Will, which I in sport do sing,

Hadst thou not played some kingly parts in sport

Thou hadst been a companion for a king,

And been a king among the meaner sort.

Some others rail; but rail as they think fit,

Thou hast no railing but a reigning wit,

And honesty thou sow’st, which they do reap

So to increase their stock which they do keep.

John Davies, The Scourge of Folly (1610)

To Master William Shakespeare

Shakespeare, that nimble Mercury, thy brain,

Lulls many hundred Argus-eyes asleep,

So fit for all thou fashionest thy vein;

At th‘horse-foot fountain thou hast drunk full deep.

Virtue’s or vice’s theme to thee all one is.

Who loves chaste life, there’s Lucrece for a teacher;

Who list read lust, there’s Venus and Adonis,

True model of a most lascivious lecher.

Besides, in plays thy wit winds like Meander,

Whence needy new composers borrow more

Than Terence doth from Plautus or Menander.

But to praise thee aright, I want thy store.

Then let thine own works thine own worth upraise,

And help t’adorn thee with deserved bays.

Thomas Freeman, Run and a Great Cast (1614)

Inscriptions upon the Shakespeare monument, Stratford-upon-Avon

Iudicio Pylium, genio Socratem, arte Maronem, Terra tegit, populus maeret, Olympus habet.

Stay, passenger, why goest thou by so fast?

Read, if thou canst, whom envious death hath placed

Within this monument: Shakespeare, with whom

Quick nature died; whose name doth deck this tomb

Far more than cost, sith all that he hath writ

Leaves living art but page to serve his wit.

Obiit anno domini 1616,

aetatis 53, die 23 Aprilis

On the death of William Shakespeare

Renowned Spenser, lie a thought more nigh

To learned Chaucer; and rare Beaumont, lie

A little nearer Spenser, to make room

For Shakespeare in your threefold, fourfold tomb.

To lodge all four in one bed make a shift

Until doomsday, for hardly will a fifth

Betwixt this day and that by fate be slain

For whom your curtains need be drawn again.

But if precedency in death doth bar

A fourth place in your sacred sepulchre,

Under this carved marble of thine own,

Sleep, rare tragedian Shakespeare, sleep alone.

Thy unmolested peace, unshared cave,

Possess as lord, not tenant, of thy grave,

That unto us or others it may be

Honour hereafter to be laid by thee.

William Basse (c.1616-22), in Shakespeare’s

Poems (1640)

The Stationer to the Reader (in The Tragedy of Othello, 1622)

To set forth a book without an epistle were like to the

old English proverb, ‘A blue coat without a badge’, and

the author being dead, I thought good to take that piece

of work upon me. To commend it I will not, for that

which is good, I hope every man will commend without

entreaty; and I am the bolder because the author’s name

is sufficient to vent his work. Thus, leaving everyone to

the liberty of judgement, I have ventured to print this

play, and leave it to the general censure.

Yours,

Thomas Walkley.

The Epistle Dedicatory (in Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, 1623)

TO THE MOST NOBLE

AND

INCOMPARABLE PAIR

OF BRETHREN

WILLIAM

Earl of Pembroke, &c., Lord Chamberlain to the

King’s most excellent majesty,

AND

PHILIP

Earl of Montgomery, &c., gentleman of his majesty’s

bedchamber; both Knights of the most noble Order

of the Garter, and our singular good

LORDS.

Right Honourable,

Whilst we study to be thankful in our particular for the many favours we have received from your lordships, we are fallen upon the ill fortune to mingle two the most diverse things that can be: fear and rashness; rashness in the enterprise, and fear of the success. For when we value the places your highnesses sustain, we cannot but know their dignity greater than to descend to the reading of these trifles; and while we name them trifles we have deprived ourselves of the defence of our dedication. But since your lordships have been pleased to think these trifles something heretofore, and have prosecuted both them and their author, living, with so much favour, we hope that, they outliving him, and he not having the fate, common with some, to be executor to his own writings, you will use the like indulgence toward them you have done unto their parent. There is a great difference whether any book choose his patrons, or find them. This hath done both; for so much were your lordships’ likings of the several parts when they were acted as, before they were published, the volume asked to be yours. We have but collected them, and done an office to the dead to procure his orphans guardians, without ambition either of self-profit or fame, only to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive as was our Shakespeare, by humble offer of his plays to your most noble patronage. Wherein, as we have justly observed no man to come near your lordships but with a kind of religious address, it hath been the height of our care, who are the presenters, to make the present worthy of your highnesses by the perfection. But there we must also crave our abilities to be considered, my lords. We cannot go beyond our own powers. Country hands reach forth milk, cream, fruits, or what they have; and many nations, we have heard, that had not gums and incense, obtained their requests with a leavened cake. It was no fault to approach their gods by what means they could, and the most, though meanest, of things are made more precious when they are dedicated to temples. In that name, therefore, we most humbly consecrate to your highnesses these remains of your servant Shakespeare, that what delight is in them may be ever your lordships’, the reputation his, and the faults ours, if any be committed by a pair so careful to show their gratitude both to the living and the dead as is

Your lordships’ most bounden,

JOHN HEMINGES.

HENRY CONDELL.

To the Great Variety of Readers

From the most able to him that can but spell: there you are numbered; we had rather you were weighed, especially when the fate of all books depends upon your capacities, and not of your heads alone, but of your purses. Well, it is now public, and you will stand for your privileges, we know: to read and censure. Do so, but buy it first. That doth best commend a book, the stationer says. Then, how odd soever your brains be, or your wisdoms, make your licence the same, and spare not. Judge your six-penn’orth, your shilling’s worth, your five shillings’ worth at a time, or higher, so you rise to the just rates, and welcome. But whatever you do, buy. Censure will not drive a trade or make the jack go; and though you be a magistrate of wit, and sit on the stage at Blackfriars or the Cockpit to arraign plays daily, know, these plays have had their trial already, and stood out all appeals, and do now come forth quitted rather by a decree of court than any purchased letters of commendation.

It had been a thing, we confess, worthy to have been wished that the author himself had lived to have set forth and overseen his own writings. But since it hath been ordained otherwise, and he by death departed from that right, we pray you do not envy his friends the office of their care and pain to have collected and published them, and so to have published them as where, before, you were abused with divers stolen and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious impostors that exposed them, even those are now offered to your view cured and perfect of their limbs, and all the rest absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them; who, as he was a happy imitator of nature, was a most gentle expresser of it. His mind and hand went together, and what he thought he uttered with that easiness that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers. But it is not our province, who only gather his works and give them you, to praise him; it is yours, that read him. And there we hope, to your diverse capacities, you will find enough both to draw and hold you; for his wit can no more lie hid than it could be lost. Read him, therefore, and again, and again, and if then you do not like him, surely you are in some manifest danger not to understand him. And so we leave you to other of his friends whom if you need can be your guides; if you need them not, you can lead yourselves and others. And such readers we wish him.

John Heminges, Henry Condell, in Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1623)

To the memory of my beloved, The AUTHOR

MASTER WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, AND what he hath left us

To draw no envy, Shakespeare, on thy name

Am I thus ample to thy book and fame;

While I confess thy writings to be such

As neither man nor muse can praise too much:

‘Tis true, and all men’s suffrage. But these ways

Were not the paths I meant unto thy praise,

For silliest ignorance on these may light,

Which, when it sounds at best, but echoes right;

Or blind affection, which doth ne’er advance

The truth, but gropes, and urgeth all by chance;

Or crafty malice might pretend this praise,

And think to ruin where it seemed to raise.

These are as some infamous bawd or whore

Should praise a matron: what could hurt her more?

But thou art proof against them, and indeed

Above th‘ill fortune of them, or the need.

I therefore will begin. Soul of the age!

The applause, delight, the wonder of our stage!

My Shakespeare, rise. I will not lodge thee by

Chaucer or Spenser, or bid Beaumont lie

A little further to make thee a room.

Thou art a monument without a tomb,

And art alive still while thy book doth live

And we have wits to read and praise to give.

That I not mix thee so, my brain excuses:

I mean with great but disproportioned muses.

For if I thought my judgement were of years

I should commit thee surely with thy peers,

And tell how far thou didst our Lyly outshine,

Or sporting Kyd, or Marlowe’s mighty line.

And though thou hadst small Latin and less Greek,

From thence to honour thee I would not seek

For names, but call forth thund’ring Aeschylus,

Euripides, and Sophocles to us,

Pacuvius, Accius, him of Cordova dead,

To life again, to hear thy buskin tread

And shake a stage; or, when thy socks were on,

Leave thee alone for the comparison

Of all that insolent Greece or haughty Rome

Sent forth, or since did from their ashes come.

Triumph, my Britain, thou hast one to show

To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe.

He was not of an age, but for all time,

And all the muses still were in their prime

When like Apollo he came forth to warm

Our ears, or like a Mercury to charm!

Nature herself was proud of his designs,

And joyed to wear the dressing of his lines,

Which were so richly spun, and woven so fit,

As since she will vouchsafe no other wit.

The merry Greek, tart Aristophanes,

Neat Terence, witty Plautus, now not please,

But antiquated and deserted lie

As they were not of nature’s family.

Yet must I not give nature all; thy art,

My gentle Shakespeare, must enjoy a part.