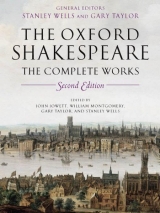

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 115 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

3.7 Enter the Constable, Lord Rambures, the Dukes of Orléans and ⌈Bourbon⌉, with others

CONSTABLE Tut, I have the best armour of the world. Would it were day.

ORLEANS You have an excellent armour. But let my horse have his due.

CONSTABLE It is the best horse of Europe.

ORLÉANS Will it never be morning?

⌈BOURBON⌉ My lord of Orléans and my Lord High Constable, you talk of horse and armour?

ORLÉANS You are as well provided of both as any prince in the world.

⌈BOURBON⌉ What a long night is this! I will not change my horse with any that treads but on four pasterns. Ah ha! He bounds from the earth as if his entrails were hares-le cheval volant, the Pegasus, qui a les narines de feu! When I bestride him, I soar, I am a hawk; he trots the air, the earth sings when he touches it, the basest horn of his hoof is more musical than the pipe of Hermes.

ORLÉANS He’s of the colour of the nutmeg.

⌈BOURBON⌉ And of the heat of the ginger. It is a beast for Perseus. He is pure air and fire, and the dull elements of earth and water never appear in him, but only in patient stillness while his rider mounts him. He is indeed a horse, and all other jades you may call beasts.

CONSTABLE Indeed, my lord, it is a most absolute and excellent horse.

⌈BOURBON⌉ It is the prince of palfreys. His neigh is like the bidding of a monarch, and his countenance enforces homage.

ORLÉANS No more, cousin.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Nay, the man hath no wit, that cannot from the rising of the lark to the lodging of the lamb vary deserved praise on my palfrey. It is a theme as fluent as the sea. Turn the sands into eloquent tongues, and my horse is argument for them all. ‘Tis a subject for a sovereign to reason on, and for a sovereign’s sovereign to ride on, and for the world, familiar to us and unknown, to lay apart their particular functions, and wonder at him. I once writ a sonnet in his praise, and began thus: ‘Wonder of nature!—’

ORLÉANS I have heard a sonnet begin so to one’s mistress.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Then did they imitate that which I composed to my courser, for my horse is my mistress.

ORLÉANS Your mistress bears well.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Me well, which is the prescribed praise and perfection of a good and particular mistress.

CONSTABLE Nay, for methought yesterday your mistress shrewdly shook your back.

⌈BOURBON⌉ So perhaps did yours.

CONSTABLE Mine was not bridled.

⌈BOURBON⌉ O then belike she was old and gentle, and you rode like a kern of Ireland, your French hose off, and in your strait strossers.

CONSTABLE You have good judgement in horsemanship.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Be warned by me then: they that ride so, and ride not warily, fall into foul bogs. I had rather have my horse to my mistress.

CONSTABLE I had as lief have my mistress a jade.

⌈BOURBON⌉ I tell thee, Constable, my mistress wears his own hair.

CONSTABLE I could make as true a boast as that, if I had a sow to my mistress.

⌈BOURBON⌉ ‛Le chien est retourné à son propre vomissement, et la truie lavée au bourbier.’ Thou makest use of anything.

CONSTABLE Yet do I not use my horse for my mistress, or any such proverb so little kin to the purpose.

RAMBURES My Lord Constable, the armour that I saw in your tent tonight, are those stars or suns upon it?

CONSTABLE Stars, my lord.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Some of them will fall tomorrow, I hope.

CONSTABLE And yet my sky shall not want.

⌈BOURBON⌉ That may be, for you bear a many superfluously, and ’twere more honour some were away.

CONSTABLE Even as your horse bears your praises, who would trot as well were some of your brags dismounted.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Would I were able to load him with his desert! Will it never be day? I will trot tomorrow a mile, and my way shall be paved with English faces.

CONSTABLE I will not say so, for fear I should be faced out of my way. But I would it were morning, for I would fain be about the ears of the English.

RAMBURES Who will go to hazard with me for twenty prisoners?

CONSTABLE You must first go yourself to hazard, ere you have them.

⌈BOURBON⌉ ’Tis midnight. I’ll go arm myself. Exit

ORLÉANS The Duke of Bourbon longs for morning.

RAMBURES He longs to eat the English.

CONSTABLE I think he will eat all he kills.

ORLÉANS By the white hand of my lady, he’s a gallant prince.

CONSTABLE Swear by her foot, that she may tread out the oath.

ORLÉANS He is simply the most active gentleman of France.

CONSTABLE Doing is activity, and he will still be doing.

ORLÉANS He never did harm that I heard of.

CONSTABLE Nor will do none tomorrow. He will keep that good name still.

ORLÉANS I know him to be valiant.

CONSTABLE I was told that by one that knows him better than you.

ORLÉANS What’s he?

CONSTABLE Marry, he told me so himself, and he said he cared not who knew it.

ORLÉANS He needs not; it is no hidden virtue in him.

CONSTABLE By my faith, sir, but it is. Never anybody saw it but his lackey. ’Tis a hooded valour, and when it appears it will bate.

ORLÉANS ‘Ill will never said well.’ no

CONSTABLE I will cap that proverb with ‘There is flattery in friendship.’

ORLÉANS And I will take up that with ‘Give the devil his due.’

CONSTABLE Well placed! There stands your friend for the devil. Have at the very eye of that proverb with ‘A pox of the devil!’

ORLÉANS You are the better at proverbs by how much ‘a fool’s bolt is soon shot’.

CONSTABLE You have shot over.

ORLÉANS ’Tis not the first time you were overshot. Enter a Messenger

MESSENGER My Lord High Constable, the English lie within fifteen hundred paces of your tents.

CONSTABLE Who hath measured the ground?

MESSENGER The Lord Grandpré.

CONSTABLE A valiant and most expert gentleman.

⌈Exit Messenger⌉

Would it were day! Alas, poor Harry of England. He

longs not for the dawning as we do.

ORLÉANS What a wretched and peevish fellow is this King of England, to mope with his fat-brained followers so far out of his knowledge.

CONSTABLE If the English had any apprehension, they would run away.

ORLÉANS That they lack—for if their heads had any intellectual armour, they could never wear such heavy headpieces.

RAMBURES That island of England breeds very valiant creatures. Their mastiffs are of unmatchable courage.

ORLÉANS Foolish curs, that run winking into the mouth of a Russian bear, and have their heads crushed like rotten apples. You may as well say, ‘That’s a valiant flea that dare eat his breakfast on the lip of a lion.’

CONSTABLE Just, just. And the men do sympathize with the mastiffs in robustious and rough coming on, leaving their wits with their wives. And then, give them great meals of beef, and iron and steel, they will eat like wolves and fight like devils.

ORLÉANS Ay, but these English are shrewdly out of beef.

CONSTABLE Then shall we find tomorrow they have only stomachs to eat, and none to fight. Now is it time to arm. Come, shall we about it?

ORLÉANS

It is now two o’clock. But let me see—by ten

We shall have each a hundred Englishmen.

Exeunt

4.0 Enter Chorus

CHORUS

Now entertain conjecture of a time

When creeping murmur and the poring dark

Fills the wide vessel of the universe.

From camp to camp through the foul womb of night

The hum of either army stilly sounds,

That the fixed sentinels almost receive

The secret whispers of each other’s watch.

Fire answers fire, and through their paly flames

Each battle sees the other’s umbered face.

Steed threatens steed, in high and boastful neighs

Piercing the night’s dull ear, and from the tents

The armourers, accomplishing the knights,

With busy hammers closing rivets up,

Give dreadful note of preparation.

The country cocks do crow, the clocks do toll

And the third hour of drowsy morning name.

Proud of their numbers and secure in soul,

The confident and overlusty French

Do the low-rated English play at dice,

And chide the cripple tardy-gaited night,

Who like a foul and ugly witch doth limp

So tediously away. The poor condemned English,

Like sacrifices, by their watchful fires

Sit patiently and inly ruminate

The morning’s danger; and their gesture sad,

Investing lank lean cheeks and war-worn coats,

Presented them unto the gazing moon

So many horrid ghosts. O now, who will behold

The royal captain of this ruined band

Walking from watch to watch, from tent to tent,

Let him cry, ‘Praise and glory on his head!’

For forth he goes and visits all his host,

Bids them good morrow with a modest smile

And calls them brothers, friends, and countrymen.

Upon his royal face there is no note

How dread an army hath enrounded him;

Nor doth he dedicate one jot of colour

Unto the weary and all-watchèd night,

But freshly looks and overbears attaint

With cheerful semblance and sweet majesty,

That every wretch, pining and pale before,

Beholding him, plucks comfort from his looks.

A largess universal, like the sun,

His liberal eye doth give to everyone,

Thawing cold fear, that mean and gentle all

Behold, as may unworthiness define,

A little touch of Harry in the night.

And so our scene must to the battle fly,

Where O for pity, we shall much disgrace,

With four or five most vile and ragged foils,

Right ill-disposed in brawl ridiculous,

The name of Agincourt. Yet sit and see,

Minding true things by what their mock’ries be. Exit

4.1 Enter King Harry and the Duke of Gloucester, then the Duke of ⌈Clarence⌉

KING HARRY

Gloucester, ’tis true that we are in great danger;

The greater therefore should our courage be.

Good morrow, brother Clarence. God Almighty!

There is some soul of goodness in things evil,

Would men observingly distil it out—

For our bad neighbour makes us early stirrers,

Which is both healthful and good husbandry.

Besides, they are our outward consciences,

And preachers to us all, admonishing

That we should dress us fairly for our end.

Thus may we gather honey from the weed

And make a moral of the devil himself.

Enter Sir Thomas Erpingham

Good morrow, old Sir Thomas Erpingham.

A good soft pillow for that good white head

Were better than a churlish turf of France.

ERPINGHAM

Not so, my liege. This lodging likes me better,

Since I may say, ‘Now lie I like a king.’

KING HARRY

’Tis good for men to love their present pains

Upon example. So the spirit is eased,

And when the mind is quickened, out of doubt

The organs, though defunct and dead before,

Break up their drowsy grave and newly move

With casted slough and fresh legerity.

Lend me thy cloak, Sir Thomas.

He puts on Erpingham’s cloak

Brothers both,

Commend me to the princes in our camp.

Do my good morrow to them, and anon

Desire them all to my pavilion.

GLOUCESTER We shall, my liege.

ERPINGHAM Shall I attend your grace?

KING HARRY No, my good knight. Go with my brothers to my lords of England. I and my bosom must debate awhile, And then I would no other company.

ERPINGHAM The Lord in heaven bless thee, noble Harry.

KING HARRY

God-a-mercy, old heart, thou speak’st cheerfully.

Exeunt all but King Harry

Enter Pistol ⌈to him⌉

PISTOL Qui vous là?

KING HARRY A friend.

PISTOL

Discuss unto me: art thou officer,

Or art thou base, common, and popular?

KING HARRY I am a gentleman of a company.

PISTOL Trail’st thou the puissant pike?

KING HARRY Even so. What are you?

PISTOL

As good a gentleman as the Emperor.

KING HARRY Then you are a better than the King.

PISTOL

The King’s a bawcock and a heart-of-gold,

A lad of life, an imp of fame,

Of parents good, of fist most valiant.

I kiss his dirty shoe, and from heartstring

I love the lovely bully. What is thy name?

KING HARRY Harry le roi.

PISTOL Leroi? A Cornish name. Art thou of Cornish crew?

KING HARRY No, I am a Welshman.

PISTOL Know’st thou Fluellen?

KING HARRY Yes.

PISTOL

Tell him I’ll knock his leek about his pate

Upon Saint Davy’s day.

KING HARRY Do not you wear your dagger in your cap that day, lest he knock that about yours.

PISTOL Art thou his friend?

KING HARRY And his kinsman too.

PISTOL The fico for thee then.

KING HARRY I thank you. God be with you.

PISTOL My name is Pistol called.

KING HARRY It sorts well with your fierceness.

Exit Pistol Enter Captains Fluellen and Gower ⌈severally⌉. King Harry stands apart

GOWER Captain Fluellen!

FLUELLEN So! In the name of Jesu Christ, speak fewer. It is the greatest admiration in the universal world, when the true and ancient prerogatifs and laws of the wars is not kept. If you would take the pains but to examine the wars of Pompey the Great, you shall find, I warrant you, that there is no tiddle-taddle nor pibble-babble in Pompey’s camp. I warrant you, you shall find the ceremonies of the wars, and the cares of it, and the forms of it, and the sobriety of it, and the modesty of it, to be otherwise.

GOWER Why, the enemy is loud. You hear him all night.

FLUELLEN If the enemy is an ass and a fool and a prating coxcomb, is it meet, think you, that we should also, look you, be an ass and a fool and a prating coxcomb? In your own conscience now?

GOWER I will speak lower.

FLUELLEN I pray you and beseech you that you will.

Exeunt Fluellen and Gower

KING HARRY

Though it appear a little out of fashion,

There is much care and valour in this Welshman.

Enter three soldiers: John Bates, Alexander Court, and Michael Williams

COURT Brother John Bates, is not that the morning which breaks yonder?

BATES I think it be. But we have no great cause to desire the approach of day.

WILLIAM We see yonder the beginning of the day, but I think we shall never see the end of it.—Who goes there?

KING HARRY A friend.

WILLIAM Under what captain serve you?

KING HARRY Under Sir Thomas Erpingham.

WILLIAM A good old commander and a most kind gentleman. I pray you, what thinks he of our estate?

KING HARRY Even as men wrecked upon a sand, that look to be washed off the next tide.

BATES He hath not told his thought to the King?

KING HARRY No, nor it is not meet he should. For though I speak it to you, I think the King is but a man, as I am. The violet smells to him as it doth to me; the element shows to him as it doth to me. All his senses have but human conditions. His ceremonies laid by, in his nakedness he appears but a man, and though his affections are higher mounted than ours, yet when they stoop, they stoop with the like wing. Therefore, when he sees reason of fears, as we do, his fears, out of doubt, be of the same relish as ours are. Yet, in reason, no man should possess him with any appearance of fear, lest he, by showing it, should dishearten his army.

BATES He may show what outward courage he will, but I believe, as cold a night as ’tis, he could wish himself in Thames up to the neck. And so I would he were, and I by him, at all adventures, so we were quit here.

KING HARRY By my troth, I will speak my conscience of the King. I think he would not wish himself anywhere but where he is.

BATES Then I would he were here alone. So should he be sure to be ransomed, and a many poor men’s lives saved.

KING HARRY I dare say you love him not so ill to wish him here alone, howsoever you speak this to feel other men’s minds. Methinks I could not die anywhere so contented as in the King’s company, his cause being just and his quarrel honourable.

WILLIAMS That’s more than we know.

BATES Ay, or more than we should seek after. For we know enough if we know we are the King’s subjects. If his cause be wrong, our obedience to the King wipes the crime of it out of us.

WILLIAMS But if the cause be not good, the King himself hath a heavy reckoning to make, when all those legs and arms and heads chopped off in a battle shall join together at the latter day, and cry all, ‘We died at such a ptace’—some swearing, some crying for a surgeon, some upon their wives left poor behind them, some upon the debts they owe, some upon their children rawly left. I am afeard there are few die well that die in a battle, for how can they charitably dispose of anything, when blood is their argument? Now, if these men do not die well, it will be a black matter for the King that led them to it—who to disobey were against all proportion of subjection.

KING HARRY So, if a son that is by his father sent about merchandise do sinfully miscarry upon the sea, the imputation of his wickedness, by your rule, should be imposed upon his father, that sent him. Or if a servant, under his master’s command transporting a sum of money, be assailed by robbers, and die in many irreconciled iniquities, you may call the business of the master the author of the servant’s damnation. But this is not so. The King is not bound to answer the particular endings of his soldiers, the father of his son, nor the master of his servant, for they purpose not their deaths when they propose their services. Besides, there is no king, be his cause never so spotless, if it come to the arbitrament of swords, can try it out with all unspotted soldiers. Some, peradventure, have on them the guilt of premeditated and contrived murder; some, of beguiling virgins with the broken seals of perjury; some, making the wars their bulwark, that have before gored the gentle bosom of peace with pillage and robbery. Now, if these men have defeated the law and outrun native punishment, though they can outstrip men, they have no wings to fly from God. War is his beadle. War is his vengeance. So that here men are punished for before-breach of the King’s laws, in now the King’s quarrel. Where they feared the death, they have borne life away; and where they would be safe, they perish. Then if they die unprovided, no more is the King guilty of their damnation than he was before guilty of those impieties for the which they are now visited. Every subject’s duty is the King’s, but every subject’s soul is his own. Therefore should every soldier in the wars do as every sick man in his bed: wash every mote out of his conscience. And dying so, death is to him advantage; or not dying, the time was blessedly lost wherein such preparation was gained. And in him that escapes, it were not sin to think that, making God so free an offer, he let him outlive that day to see his greatness and to teach others how they should prepare.

⌈BATES⌉ ’Tis certain, every man that dies ill, the ill upon his own head. The King is not to answer it. I do not desire he should answer for me, and yet I determine to fight lustily for him.

KING HARRY I myself heard the King say he would not be ransomed.

WILLIAMS Ay, he said so, to make us fight cheerfully, but when our throats are cut he may be ransomed, and we ne’er the wiser.

KING HARRY If I live to see it, I will never trust his word after.

WILLIAMS You pay him then! That’s a perilous shot out of an elder-gun, that a poor and a private displeasure can do against a monarch. You may as well go about to turn the sun to ice with fanning in his face with a peacock’s feather. You’ll never trust his word after! Come, ’tis a foolish saying.

KING HARRY Your reproof is something too round. I should be angry with you, if the time were convenient.

WILLIAMS Let it be a quarrel between us, if you live.

KING HARRY I embrace it.

WILLIAM How shall I know thee again?

KING HARRY Give me any gage of thine, and I will wear it in my bonnet. Then if ever thou darest acknowledge it, I will make it my quarrel.

WILLIAMS Here’s my glove. Give me another of thine.

KING HARRY There. They exchange gloves

WILLIAM This will I also wear in my cap. If ever thou come to me and say, after tomorrow, ‘This is my glove’, by this hand I will take thee a box on the ear.

KING HARRY If ever I live to see it, I will challenge it.

WILLIAM Thou darest as well be hanged.

KING HARRY Well, I will do it, though I take thee in the King’s company.

WILLIAMS Keep thy word. Fare thee well.

BATES Be friends, you English fools, be friends. We have French quarrels enough, if you could tell how to reckon.

KING HARRY Indeed, the French may lay twenty French crowns to one they will beat us, for they bear them on their shoulders. But it is no English treason to cut French crowns, and tomorrow the King himself will be a clipper. Exeunt soldiers Upon the King. ‘Let us our lives, our souls, our debts, our care-full wives, Our children, and our sins, lay on the King.’ We must bear all. O hard condition, Twin-born with greatness: subject to the breath Of every fool, whose sense no more can feel But his own wringing. What infinite heartsease Must kings neglect that private men enjoy? And what have kings that privates have not too, Save ceremony, save general ceremony? And what art thou, thou idol ceremony? What kind of god art thou, that suffer‘st more Of mortal griefs than do thy worshippers? What are thy rents? What are thy comings-in? O ceremony, show me but thy worth. What is thy soul of adoration? Art thou aught else but place, degree, and form, Creating awe and fear in other men? Wherein thou art less happy, being feared, Than they in fearing. What drink’st thou oft, instead of homage sweet, But poisoned flattery? O be sick, great greatness, And bid thy ceremony give thee cure. Think‘st thou the fiery fever will go out With titles blown from adulation? Will it give place to flexure and low bending? Canst thou, when thou command’st the beggar’s knee, Command the health of it? No, thou proud dream That play‘st so subtly with a king’s repose; I am a king that find thee, and I know ’Tis not the balm, the sceptre, and the ball, The sword, the mace, the crown imperial, The intertissued robe of gold and pearl, The farced title running fore the king, The throne he sits on, nor the tide of pomp That beats upon the high shore of this world—No, not all these, thrice-gorgeous ceremony, Not all these, laid in bed majestical, Can sleep so soundly as the wretched slave Who with a body filled and vacant mind Gets him to rest, crammed with distressful bread; Never sees horrid night, the child of hell, But like a lackey from the rise to set Sweats in the eye of Phoebus, and all night Sleeps in Elysium; next day, after dawn Doth rise and help Hyperion to his horse, And follows so the ever-running year With profitable labour to his grave. And but for ceremony such a wretch, Winding up days with toil and nights with sleep, Had the forehand and vantage of a king. The slave, a member of the country’s peace, Enjoys it, but in gross brain little wots What watch the King keeps to maintain the peace, Whose hours the peasant best advantages. Enter Sir Thomas Erpingham

ERPINGHAM

My lord, your nobles, jealous of your absence,

Seek through your camp to find you.

KING HARRY

Good old knight,

Collect them all together at my tent.

I’ll be before thee.

ERPINGHAM

I shall do’t, my lord. Exit

KING HARRY

O God of battles, steel my soldiers’ hearts.

Possess them not with fear. Take from them now

The sense of reck‘ning, ere th’opposèd numbers

Pluck their hearts from them. Not today, O Lord,

O not today, think not upon the fault

My father made in compassing the crown.

I Richard’s body have interred new,

And on it have bestowed more contrite tears

Than from it issued forced drops of blood.

Five hundred poor have I in yearly pay

Who twice a day their withered hands hold up

Toward heaven to pardon blood. And I have built

Two chantries, where the sad and solemn priests

Sing still for Richard’s soul. More will I do,

Though all that I can do is nothing worth,

Since that my penitence comes after ill,

Imploring pardon.

Enter the Duke of Gloucester

GLOUCESTER

My liege.

KING HARRY My brother Gloucester’s voice? Ay.

I know thy errand, I will go with thee.

The day, my friends, and all things stay for me.

Exeunt