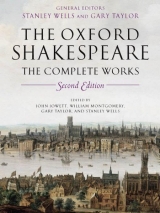

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

Table of Contents

Praise

Title Page

Copyright Page

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Acknowledgements

Introduction

A USER’S GUIDE TO THE COMPLETE WORKS

THE LANGUAGE OF SHAKESPEARE

CONTEMPORARY ALLUSIONS TO SHAKESPEARE

COMMENDATORY POEMS AND PREFACES (1599-1640)

THE COMPLETE WORKS

THE TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

THE TAMING OF THE SHREW

The Taming of the Shrew

THE FIRST PART OF THE CONTENTION – (2 HENRY VI)

The First Part of the Contention of the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster

RICHARD DUKE OF YORK – (3 HENRY VI)

The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York and the Good King Henry the Sixth

HENRY VI PART ONE

The First Part of Henry the Sixth

TITUS ANDRONICUS

The Most Lamentable Roman Tragedy of Titus Andronicus

RICHARD III

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third

VENUS AND ADONIS

Venus and Adonis

THE RAPE OF LUCRECE

The Rape of Lucrece

EDWARD III

The Reign of King Edward the Third

THE COMEDY OF ERRORS

The Comedy of Errors

LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST

Love’s Labour’s Lost

LOVE’S LABOUR’S WON – A BRIEF ACCOUNT

RICHARD II

The Tragedy of King Richard the Second

ROMEO AND JULIET

The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

KING JOHN

The Life and Death of King John

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE

The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice, or Otherwise Called the Jew of Venice

1 HENRY IV

The History of Henry the Fourth

THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR

The Merry Wives of Windsor

2 HENRY IV

The Second Part of Henry the Fourth

MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING

Much Ado About Nothing

HENRY V

The Life of Henry the Fifth

JULIUS CAESAR

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

AS YOU LIKE IT

As You Like It

HAMLET

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night, or What You Will

TROILUS AND CRESSIDA

Troilus and Cressida

SONNETS AND ‘A LOVER’S COMPLAINT’

Sonnets

A Lover’s Complaint

VARIOUS POEMS

Various Poems

SIR THOMAS MORE

NOTE ON SPECIAL FEATURES OF PRESENTATION

The Book of Sir Thomas More

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

Measure for Measure

OTHELLO

The Tragedy of Othello the Moor of Venice

THE HISTORY OF KING LEAR – THE QUARTO TEXT

The History of King Lear

TIMON OF ATHENS

The Life of Timon of Athens

MACBETH

The Tragedy of Macbeth

ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA

The Tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra

ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL

All’s Well That Ends Well

PERICLES

A Reconstructed Text of Pericles, Prince of Tyre

CORIOLANUS

The Tragedy of Coriolanus

THE WINTER’S TALE

The Winter’s Tale

THE TRAGEDY OF KING LEAR – THE FOLIO TEXT

The Tragedy of King Lear

CYMBELINE

Cymbeline, King of Britain

THE TEMPEST

The Tempest

CARDENIO – A BRIEF ACCOUNT

ALL IS TRUE – (HENRY VIII)

All Is True

THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN

The Two Noble Kinsmen

FURTHER READING

A SELECT GLOSSARY

INDEX OF FIRST LINES OF SONNETS

Martin Droeshout’s engraving of Shakespeare, first published on the title-page of the First Folio (1623)

To the Reader

This figure that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,

Wherein the graver had a strife

With nature to outdo the life.

O, could he but have drawn his wit

As well in brass as he hath hit

His face, the print would then surpass

All that was ever writ in brass!

But since he cannot, reader, look

Not on his picture, but his book.

BEN JOHNSON

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0x2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

© Oxford University Press 1986, 2005

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

Hardback first published 1986

Hardback compact edition 1988

Paperback compact edition 1994

Second edition published 2005

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data applied for

ISBN 0-19-926717-O (hbk)

ISBN 0-19-926718-9 (pbk)

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Printed in Italy by Legoprint

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

THE COMPLETE WORKS

with a General Introduction, and Introductions to individual works, by

STANLEY WELLS

The Complete Works has been edited collaboratively under the General Editorship of Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor. Each editor has undertaken prime responsibility for certain works, as follows:

STANLEY WELLS The Two Gentlemen of Verona; The Taming of the Shrew; Titus Andronicus; Venus and Adonis; The Rape of Lucrece; Love’s Labour’s Lost; Much Ado About Nothing; As You Like It; Twelfth Night; The Sonnets and ‘A Lover’s Complaint’; Various Poems (printed); Othello; Macbeth; Antony and Cleopatra; The Winter’s Tale

GARY TAYLOR I Henry VI; Richard III; The Comedy of Errors; A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Henry V; Hamlet; Troilus and Cressida; Various Poems (manuscript); All’s Well That Ends Well; King Lear; Pericles; Cymbeline

JOHN JOWETT Richard II; Romeo and Juliet; King John; I Henry IV; The Merry Wives of Windsor; 2 Henry IV; Julius Caesar; Sir Thomas More; Measure for Measure; Timon of Athens; Coriolanus; The Tempest

WILLIAM MONTGOMERY The First Part of the Contention; Richard Duke of York; Edward III; The Merchant of Venice; All Is True; The Two Noble Kinsmen

American Advisory Editor · S. Schoenbaum

Textual Adviser · G. R. Proudfoot

Music Adviser · F. W. Sternfeld

Editorial Assistant · Christine Avern-Carr

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THE preparation of a volume such as this would be impossible without the generosity that scholars can count on receiving from their colleagues, at home and overseas. Among those to whom we are particularly grateful are: R. E. Alton; John P. Andrews; Peter Beal; Thomas L. Berger; David Bevington; J. W. Binns; Peter W. M. Blayney; Fredson Bowers; A. W. Braunmuller; Alan Brissenden; Susan Brock; J. P. Brockbank; Robert Burchfield; Lou Burnard; Lesley Burnett; John Carey; Janet Clare; Thomas Clayton; T. W. Craik; Norman Davis; Alan Dessen; E. E. Duncan-Jones; K. Duncan-Jones; R. D. Eagleson; Philip Edwards; G. Blakemore Evans; Jean Fuzier; Hans Walter Gabler; Philip Gaskell; A. J. Gurr; Antony Hammond; Richard Hardin; G. R. Hibbard; Myra Hinman; R. V. Holdsworth; E. A. J. Honigmann; T. H. Howard-Hill; MacD. P. Jackson; Harold Jenkins; Charles Johnston; John Kerrigan; Randall McLeod; Nancy Maguire; Giorgio Melchiori; Peter Milward; Kenneth Muir; Stephen Orgel; Kenneth Palmer; John Pitcher; Eleanor Prosser; S. W. Reid; Marvin Spevack; R. K. Turner; E. M. Waith; Michael Warren; R. J. C. Watt; Paul Werstine; G. Walton Williams; Laetitia Yeandle.

We are conscious also of a great debt to the past: to our predecessors R. B. McKerrow and Alice Walker, who did not live to complete an Oxford Shakespeare but whose papers have been of invaluable assistance, and to the long line of editors and other scholars, from Nicholas Rowe onwards, whose work is acknowledged in William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion.

We gratefully acknowledge assistance from the staff of the following libraries and institutions: the Beinecke Library, Yale University; the Birmingham Shakespeare Library; the Bodleian Library, Oxford; the British Library; the English Faculty Library, Oxford; the Folger Shakespeare Library; Lambeth Palace Library; St. John’s College, Cambridge; the Shakespeare Centre, Stratford-upon-Avon; the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham; Trinity College, Cambridge; the Victoria and Albert Museum; Westminster Abbey Library.

Many debts of gratitude have also been incurred to persons employed in a variety of capacities by Oxford University Press. Among those with whom we have worked especially closely are Linda Agerbak, Sue Dommett, Oonagh Ferrier, Paul Luna, Jamie Mackay, Louise Pengelley, Graham Roberts, Maria Tsoutsos, and Patricia Wilkie. John Bell started it all, Kim Scott Walwyn made sure we finished it, and from beginning to end Christine Avern-Carr’s meticulous standards of accuracy have been exemplary.

S.W.W. G.T.

J.J. W.L.M.

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

THIS volume contains all the known plays and poems of William Shakespeare, a writer, actor, and man of the theatre who lived from 1564 to 1616. He was successful and admired in his own time; major literary figures of the subsequent century, such as John Milton, John Dryden, and Alexander Pope, paid tribute to him, and some of his plays continued to be acted during the later seventeenth and earlier eighteenth centuries; but not until the dawn of Romanticism, in the later part of the eighteenth century, did he come to be looked upon as a universal genius who outshone all his fellows and even, some said, partook of the divine. Since then, no other secular imaginative writer has exerted so great an influence over so large a proportion of the world’s population. Yet Shakespeare’s work is firmly rooted in the circumstances of its conception and development. Its initial success depended entirely on its capacity to please the theatre-goers (and, to a far lesser extent, the readers) of its time; and its later, profound impact is due in great part to that in-built need for constant renewal and adaptation that belongs especially to those works of art that reach full realization only in performance. Shakespeare’s power over generations later than his own has been transmitted in part by artists who have drawn on, interpreted, and restructured his texts as others have drawn on the myths of antiquity; but it is the texts as they were originally performed that are the sources of his power, and that we attempt here to present with as much fidelity to his intentions as the circumstances in which they have been preserved will allow.

Shakespeare’s Life: Stratford-upon-Avon and London

Shakespeare’s background was commonplace. His father, John, was a glover and wool-dealer in the small Midlands market-town of Stratford-upon-Avon who had married Mary Arden, daughter of a prosperous farmer, in or about 1557. During Shakespeare’s childhood his father played a prominent part in local affairs, becoming bailiff (mayor) and justice of the peace in 1568; later his fortunes declined. Of his eight children, four sons and one daughter survived childhood. William, his third child and eldest son, was baptized in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, on 26 April 1564; his birthday is traditionally celebrated on 23 April—St. George’s Day. The only other member of his family to take up the theatre as a profession was his youngest brother, Edmund, born sixteen years after William. He became an actor and died at the age of twenty-seven: on the last day of 1607 the sexton of St. Saviour‘s, Southwark, noted ‘Edmund Shakspeare A player Buried in ye Church wth a forenoone knell of ye great bell, xxs.’ The high cost of the funeral suggests that it may have been paid for by his prosperous brother.

John Shakespeare’s position in Stratford-upon-Avon would have brought certain privileges to his family. When young William was four years old he could have had the excitement of seeing his father, dressed in furred scarlet robes and wearing the alderman’s official thumb-ring, regularly accompanied by two mace-bearing sergeants in buff, presiding at fairs and markets. A little later, he would have begun to attend a ‘petty school’ to acquire the rudiments of an education that would be continued at the King’s New School, an established grammar school with a well-qualified master, assisted by an usher to help with the younger pupils. We have no lists of the school’s pupils in Shakespeare’s time, but his father’s position would have qualified him to attend, and the school offered the kind of education that lies behind the plays and poems. Its boy pupils, aged from about eight to fifteen, endured an arduous routine. Classes began early in the morning: at six, normally; hours were long, holidays infrequent. Education was centred on Latin; in the upper forms, the speaking of English was forbidden. A scene (4.1) in The Merry Wives of Windsor showing a schoolmaster taking a boy named William through his Latin grammar draws on the officially approved textbook, William Lily’s Short Introduction of Grammar, and, no doubt, on Shakespeare’s memories of his youth.

From grammar the boys progressed to studying works of classical and neo-classical literature. They might read anthologies of Latin sayings and Aesop’s Fables, followed by the fairly easy plays of Terence and Plautus (on whose Menaechmi Shakespeare was to base The Comedy of Errors). They might even act scenes from Latin plays. As they progressed, they would improve their command of language by translating from Latin into English and back, by imitating approved models of style, and by studying manuals of composition, the ancient rules of rhetoric, and modern rules of letter-writing. Putting their training into practice, they would compose formal epistles, orations, and declamations. Their efforts at composition would be stimulated, too, by their reading of the most admired authors. Works that Shakespeare wrote throughout his career show the abiding influence of Virgil’s Aeneid and of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (both in the original and in Arthur Golding’s translation of 1567). Certainly he developed a taste for books, both classical and modern: his plays show that he continued to read seriously and imaginatively for the whole of his working life.

After Shakespeare died, Ben Jonson accused him of knowing ‘small Latin and less Greek’; but Jonson took pride in his classical knowledge: a boy educated at an Elizabethan grammar school would be more thoroughly trained in classical rhetoric and Roman (if not Greek) literature than most present-day holders of a university degree in classics. Modern languages would not normally be on the curriculum. Somehow Shakespeare seems to have picked up a working knowledge of French—which he expected audiences of Henry V to understand—and of Italian (the source of Othello, for instance, is an Italian tale that had not been published in translation when he wrote his play). We do not know whether he ever travelled outside England.

Shakespeare must have worked hard at school, but there was a life beyond the classroom. He lived in a beautiful and fertile part of the country, with rivers and fields at hand. He had the company of brothers and sisters. Each Sunday the family would go to Stratford’s splendid parish church, as the law required; his father, by virtue of his dignified status, would sit in the front pew. There Shakespeare’s receptive mind would be impressed by the sonorous phrases of the Bible, in either the Bishops’ or the Geneva version, the Homilies, and the Book of Common Prayer. From time to time travelling players would visit Stratford. Shakespeare’s father would have the duty of licensing them to perform; probably his son first saw plays professionally acted in the Guildhall below his schoolroom.

Shakespeare would have left school when he was about fifteen. What he did then is not known. One of the earliest legends about him, recorded by John Aubrey around 1681, is that ‘he had been in his younger years a schoolmaster in the country’. John Cottom, who was master of the Stratford school between 1579 and 1581 or 1582, and may have taught Shakespeare, was a Lancashire man whose family home was close to that of a landowner, Alexander Houghton. Both Cottom and Houghton were Roman Catholics, and there is some reason to believe that John Shakespeare may have retained loyalties to the old religion. When Houghton died, in 1581, he mentioned in his will one William Shakeshafte, possibly a player. The name is a possible variant of Shakespeare; conceivably Cottom found employment in Lancashire again for his talented pupil as a tutor who also acted. On the other hand, the name ‘Shakeshaft’, common in Lancashire, is not found in Warwickshire. If Shakespeare did leave Stratford, he was soon back home. On 28 November 1582 a bond was issued permitting him to marry Anne Hathaway of Shottery, a village close to Stratford. She was eight years his senior, and pregnant. Their daughter, Susanna, was baptized on 26 May 1583, and twins, Hamnet and Judith, on 2 February 1585. Though Shakespeare’s professional career (described in the next section of this Introduction) was to centre on London, his family remained in Stratford, and he maintained his links with his birthplace till he died and was buried there.

I. The Shakespeare coat of arms, from a draft dated 20 October 1596, prepared by Sir William Dethick, Garter King-of-Arms

One of the unfounded myths about Shakespeare is that all we know about his life could be written on the back of a postage stamp. In fact we know a lot about some of the less exciting aspects of his life, such as his business dealings and his tax debts (as may be seen from the list of Contemporary Allusions, pp. lxv-lxviii). Though we cannot tell how often he visited Stratford after he started to work in London, clearly he felt that he belonged where he was born. His success in his profession may be reflected in his father’s application for a grant of arms in 1596, by which John Shakespeare acquired the official status of gentleman. In August of that year William’s son, Hamnet, died, aged eleven and a half, and was buried in Stratford. Shakespeare was living modestly, and, so far as we know, alone in the Bishopsgate area of London, north of the river, in October of the same year, but in the following year showed that he looked on Stratford as his real home by buying a large house, New Place. It was demolished in 1759.

In October 1598 Richard Quiney, whose son was to marry Shakespeare’s daughter Judith, travelled to London to plead with the Privy Council on behalf of Stratford Corporation, which was in financial trouble because of fires and bad weather. He wrote the only surviving letter addressed to Shakespeare; as it was found among Quiney’s papers, it was presumably never delivered. It requested a loan, possibly on behalf of the town, of £30—a large sum, suggesting confidence in his friend’s prosperity. In 1601 Shakespeare’s father died, and was buried in Stratford. In May of the following year Shakespeare was able to invest £320 in 107 acres of arable land in Old Stratford. In the same year John Manningham, a London law student, recorded a piece of gossip that gives us a rare contemporary anecdote about the private life of Shakespeare and of Richard Burbage, the leading tragedian of his company:

Upon a time when Burbage played Richard III there was a citizen grew so far in liking with him that before she went from the play she appointed him to come that night unto her by the name of Richard the Third. Shakespeare, overhearing their conclusion, went before, was entertained, and at his game ere Burbage came. Then, message being brought that Richard the Third was at the door, Shakespeare caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third.

In 1604 Shakespeare was lodging in north London with a Huguenot family called Mountjoy; in 1612 he was to testify in a court case relating to a marriage settlement on the daughter of the house. The records of the case provide our only transcript of words actually spoken by Shakespeare; they are not characterful. In 1605 Shakespeare invested £440 in the Stratford tithes, which brought him in £60 a year; in June 1607 his elder daughter, Susanna, married a distinguished physician, John Hall, in Stratford, and there his only grandchild, their daughter Elizabeth, was baptized the following February. In 1609 his mother died there, and from about 1610 his increasing involvement with Stratford along with the reduction in his dramatic output suggests that he was withdrawing from his London responsibilities and spending more time at New Place. Perhaps he was deliberately devoting himself to his family’s business interests; he was only forty-six years old: an age at which a healthy man was no more likely to retire then than now. If he was ill, he was not totally disabled, as he was in London in 1612 for the Mountjoy lawsuit. In March 1613 he bought a house in the Blackfriars area of London for £140: he is not known to have lived in it. Also in 1613 the last of his three brothers died. In late 1614 and 1615 he was involved in disputes about the enclosure of the land whose tithes he owned. In February 1616 his second daughter, Judith, married Thomas Quiney, causing William to make alterations to the draft of his will, which he signed on 25 March. His widow was entitled by law and local custom to part of his estate; he left most of the remainder to his elder daughter, Susanna, and her husband. He died on 23 April, and was buried two days later in a prominent position in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church. A monument was commissioned, presumably by members of his family, and was in position by 1623. The work of Gheerart Janssen, a stonemason whose shop was not far from the Globe Theatre, it incorporates a half-length effigy which is one of the only two surviving likenesses of Shakespeare with any strong claim to authenticity.

As this selective survey of the historical records shows, Shakespeare’s life is at least as well documented as those of most of his contemporaries who did not belong to great families; we know more about him than about any other dramatist of his time except Ben Jonson. The inscription on the Stratford landowner’s memorial links him with Socrates and Virgil; and in the far greater memorial of 1623, the First Folio edition of his plays, Jonson links this ‘Star of poets’ with his home town as the ‘Sweet swan of Avon’. The Folio includes the second reliable likeness of Shakespeare, an engraving by Martin Droeshout which, we must assume, had been commissioned and approved by his friends and colleagues who put the volume together. In the Folio it faces the lines signed ‘B.1.’ (Ben Jonson) which we print beneath it. Shakespeare’s widow died in 1623, and his last surviving descendant, Elizabeth Hall (who inherited New Place and married first a neighbour, Thomas Nash, and secondly John Bernard, knighted in 1661), in 1670.

2. Shakespeare’s monument, designed by Gheerart Janssen, in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon