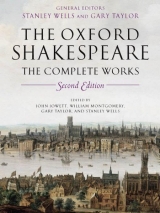

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 80 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

5.2 Enter Robin Goodfellow with a broom

ROBIN

Now the hungry lion roars,

And the wolf behowls the moon,

Whilst the heavy ploughman snores,

All with weary task fordone.

Now the wasted brands do glow

Whilst the screech-owl, screeching loud,

Puts the wretch that lies in woe

In remembrance of a shroud.

Now it is the time of night

That the graves, all gaping wide,

Every one lets forth his sprite

In the churchway paths to glide;

And we fairies that do run

By the triple Hecate’s team

From the presence of the sun,

Following darkness like a dream,

Now are frolic. Not a mouse

Shall disturb this hallowed house.

I am sent with broom before

To sweep the dust behind the door.

Enter Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of Fairies, with all their train

OBERON

Through the house give glimmering light.

By the dead and drowsy fire

Every elf and fairy sprite

Hop as light as bird from brier,

And this ditty after me

Sing, and dance it trippingly.

TITANIA

First rehearse your song by rote,

To each word a warbling note.

Hand in hand with fairy grace

Will we sing and bless this place.

⌈The song. The fairies dance⌉

OBERON

Now until the break of day

Through this house each fairy stray.

To the best bride bed will we,

Which by us shall blessèd be,

And the issue there create

Ever shall be fortunate.

So shall all the couples three

Ever true in loving be,

And the blots of nature’s hand

Shall not in their issue stand.

Never mole, harelip, nor scar,

Nor mark prodigious such as are

Despised in nativity

Shall upon their children be.

With this field-dew consecrate

Every fairy take his gait

And each several chamber bless

Through this palace with sweet peace;

And the owner of it blessed

Ever shall in safety rest.

Trip away, make no stay,

Meet me all by break of day. Exeunt all but Robin

Epilogue

ROBIN

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended:

That you have but slumbered here,

While these visions did appear;

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend.

If you pardon, we will mend.

And as I am an honest puck,

If we have unearned luck

Now to ’scape the serpent’s tongue,

We will make amends ere long,

Else the puck a liar call.

So, good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

ADDITIONAL PASSAGES

An unusual quantity and kind of mislineation in the first edition has persuaded most scholars that the text at the beginning of 5.1 was revised, with new material written in the margins. We here offer a reconstruction of the passage as originally drafted, which can be compared with 5.1.1―86 of the edited text.

5.1 Enter Theseus, Hippolyta, and Philostrate

HIPPOLYTA

’Tis strange, my Theseus, that these lovers speak of.

THESEUS

More strange than true. I never may believe

These antique fables, nor these fairy toys.

Lovers and mad men have such seething brains.

One sees more devils than vast hell can hold: 5

That is the madman. The lover, all as frantic,

Sees Helen’s beauty in a brow of Egypt.

Such tricks hath strong imagination

That if it would but apprehend some joy

It comprehends some bringer of that joy; 10

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear!

HIPPOLYTA

But all the story of the night told over,

And all their minds transfigured so together,

More witnesseth than fancy’s images, 15

And grows to something of great constancy;

But howsoever, strange and admirable.

Enter the lovers: Lysander, Demetrius, Hermia, and Helena

THESEUS

Here come the lovers, full of joy and mirth.

Come now, what masques, what dances shall we

have

To ease the anguish of a torturing hour? 20

Call Philostrate.

PHILOSTRATE Here mighty Theseus.

THESEUS

Say, what abridgement have you for this evening?

What masque, what music? How shall we beguile

The lazy time if not with some delight?

PHILOSTRATE

There is a brief how many sports are ripe. 25

Make choice of which your highness will see first.

THESEUS

‘The battle with the centaurs to be sung

By an Athenian eunuch to the harp.’

We’ll none of that. That have I told my love

In glory of my kinsman Hercules. 30

‘The riot of the tipsy Bacchanals

Tearing the Thracian singer in their rage.’

That is an old device, and it was played

When I from Thebes came last a conquerer.

‘The thrice-three Muses mourning for the death 35

Of learning, late deceased in beggary.’

That is some satire, keen and critical,

Not sorting with a nuptial ceremony.

‘A tedious brief scene of young Pyramus

And his love Thisby.’ ’Tedious’ and ‘brief’? 40

PHILOSTRATE

A play there is, my lord, some ten words long,

Which is as ‘brief as I have known a play;

But by ten words, my lord, it is too long,

Which makes it ’tedious’; for in all the play

There is not one word apt, one player fitted. 45

THESEUS What are they that do play it?

PHILOSTRATE

Hard-handed men that work in Athens here,

Which never laboured in their minds till now,

And now have toiled their unbreathed memories

With this same play against your nuptial. 50

THESEUS

Go, bring them in; and take your places, ladies.

Exit Philostrate

HIPPOLYTA

I love not to see wretchedness o’ercharged

And duty in his service perishing.

KING JOHN

A PLAY called The Troublesome Reign of John, King of England, published anonymously in 1591, has sometimes been thought to be a derivative version of Shakespeare’s King John, first published in the 1623 Folio; more probably Shakespeare wrote his play in 1595 or 1596, using The Troublesome Reign—itself based on Holinshed’s Chronicles and John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563)—as his principal source. Like Richard II, King John is written entirely in verse.

King John (c.1167―1216) was famous as the opponent of papal tyranny, and The Troublesome Reign is a violently anti-Catholic play; but Shakespeare is more moderate. He portrays selected events from John’s reign—like The Troublesome Reign, making no mention of Magna Carta—and ends with John’s death, but John is not so dominant a figure in his play as Richard II or Richard III in theirs. Indeed, the longest—and liveliest—role is that of Richard Coeur-de-lion’s illegitimate son, Philip Falconbridge, the Bastard.

King John’s reign was troublesome initially because of his weak claim to his brother Richard Coeur-de-lion’s throne. Prince Arthur, son of John’s elder brother Geoffrey, had no less strong a claim, which is upheld by his mother, Constance, and by King Philip of France. The waste and futility of the consequent war between power-hungry leaders is satirically demonstrated in the dispute over the French town of Angers, which is resolved by a marriage between John’s niece, Lady Blanche of Spain, and Louis, the French Dauphin. The moral is strikingly drawn by the Bastard—the man best fitted to be king, but debarred by accident of birth—in his speech (2.1.562-99) on ’commodity’ (self-interest). King Philip breaks his treaty with England, and in the ensuing battle Prince Arthur is captured. He becomes the play’s touchstone of humanity as he persuades John’s agent, Hubert, to disobey John’s orders to blind him, only to kill himself while trying to escape. John’s noblemen, thinking the King responsible for the boy’s death, defect to the French, but return to their allegiance on learning that the Dauphin intends to kill them after conquering England. John dies, poisoned by a monk; the play ends with the reunited noblemen swearing allegiance to John’s son, the young Henry III, and with the Bastard’s boast that

This England never did, nor never shall,

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror

But when it first did help to wound itself.

Twentieth-century revivals of King John were infrequent, but it was popular in the nineteenth century, when the roles of the King, the Bastard, and Constance all appealed to successful actors; a production of 1823 at Covent Garden inaugurated a trend for historically accurate settings and costumes which led to a number of spectacular revivals.

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

KING JOHN of England

QUEEN ELEANOR, his mother

LADY FALCONBRIDGE

Philip the BASTARD, later knighted as Sir Richard Plantagenet,

her illegitimate son by King Richard I (Coeur-de-lion)

Robert FALCONBRIDGE, her legitimate son

James GURNEY, her attendant

Lady BLANCHE of Spain, niece of King John

PRINCE HENRY, son of King John

HUBERT, a follower of King John

Earl of SALISBURY

Earl of PEMBROKE

Earl of ESSEX

Lord BIGOT

KING PHILIP of France

LOUIS THE DAUPHIN, his son

ARTHUR, Duke of Brittaine, nephew of King John

Lady coNSTANCE, his mother

Duke of AUSTRIA (Limoges)

CHÂTILLON, ambassador from France to England

Count MELUN

A CITIZEN of Angers

Cardinal PANDOLF, a legate from the Pope

PETER OF POMFRET, a prophet

HERALDS

EXECUTIONERS

MESSENGERS

SHERIFF

Lords, soldiers, attendants

The Life and Death of King John

1.1 [Flourish.] Enter King John, Queen Eleanor, and the Earls of Pembroke, Essex, and Salisbury; with them Châtillon of France

KING JOHN

Now say, Châtillon, what would France with us?

CHÂTILLON

Thus, after greeting, speaks the King of France,

In my behaviour, to the majesty—

The borrowed majesty—of England here.

QUEEN ELEANOR

A strange beginning: ‘borrowed majesty’?

KING JOHN

Silence, good mother, hear the embassy.

CHÂTILLON

Philip of France, in right and true behalf

Of thy deceased brother Geoffrey’s son,

Arthur Plantagenet, lays most lawful claim

To this fair island and the territories,

To Ireland, Poitou, Anjou, Touraine, Maine;

Desiring thee to lay aside the sword

Which sways usurpingly these several titles,

And put the same into young Arthur’s hand,

Thy nephew and right royal sovereign.

KING JOHN

What follows if we disallow of this?

CHÂTILLON

The proud control of fierce and bloody war,

To enforce these rights so forcibly withheld—

KING JOHN

Here have we war for war, and blood for blood,

Controlment for controlment: so answer France.

CHÂTILLON

Then take my king’s defiance from my mouth,

The farthest limit of my embassy.

KING JOHN

Bear mine to him, and so depart in peace.

Be thou as lightning in the eyes of France,

For ere thou canst report, I will be there; 25

The thunder of my cannon shall be heard.

So hence. Be thou the trumpet of our wrath,

And sullen presage of your own decay.—

An honourable conduct let him have;

Pembroke, look to’t.—Farewell, Châtillon. 30

Exeunt Châtillon and Pembroke

QUEEN ELEANOR

What now, my son? Have I not ever said

How that ambitious Constance would not cease

Till she had kindled France and all the world

Upon the right and party of her son ?

This might have been prevented and made whole 35

With very easy arguments of love,

Which now the manage of two kingdoms must

With fearful-bloody issue arbitrate.

KING JOHN

Our strong possession and our right for us.

QUEEN ELEANOR (aside to King John)

Your strong possession much more than your right,

Or else it must go wrong with you and me: 41

So much my conscience whispers in your ear,

Which none but heaven and you and I shall hear.

Enter a Sheriff, [who whispers to Essex]

ESSEX

My liege, here is the strangest controversy,

Come from the country to be judged by you, 45

That e’er I heard. Shall I produce the men?

KING JOHN Let them approach.—⌈Exit Sheriff⌉

Our abbeys and our priories shall pay

This expeditious charge.

Enter Robert Falconbridge and Philip the Bastard ⌈With the Sheriff⌉

What men are you?

BASTARD

Your faithful subject I, a gentleman 50

Born in Northamptonshire, and eldest son,

As I suppose, to Robert Falconbridge,

A soldier, by the honour-giving hand

Of Cœur-de-lion knighted in the field.

KING JOHN What art thou? 55

FALCONBRIDGE

The son and heir to that same Falconbridge.

KING JOHN

Is that the elder, and art thou the heir?

You came not of one mother then, it seems.

BASTARD

Most certain of one mother, mighty King—

That is well known—and, as I think, one father. 60

But for the certain knowledge of that truth

I put you o’er to heaven, and to my mother.

Of that I doubt as all men’s children may.

QUEEN ELEANOR

Out on thee, rude man ! Thou dost shame thy mother

And wound her honour with this diffidence. 65

BASTARD

I, Madam? No, I have no reason for it.

That is my brother’s plea and none of mine,

The which if he can prove, a pops me out

At least from fair five hundred pound a year.

Heaven guard my mother’s honour, and my land! 70

KING JOHN

A good blunt fellow.—Why, being younger born,

Doth he lay claim to thine inheritance ?

BASTARD

I know not why, except to get the land;

But once he slandered me with bastardy.

But whe’er I be as true begot or no, 75

That still I lay upon my mother’s head;

But that I am as well begot, my liege—

Fair fall the bones that took the pains for me—

Compare our faces and be judge yourself.

If old Sir Robert did beget us both 80

And were our father, and this son like him,

O old Sir Robert, father, on my knee

I give heaven thanks I was not like to thee.

KING JOHN

Why, what a madcap hath heaven lent us here!

QUEEN ELEANOR

He hath a trick of Coeur-de-lion’s face; 85

The accent of his tongue affecteth him.

Do you not read some tokens of my son

In the large composition of this man?

KING JOHN

Mine eye hath well examined his parts,

And finds them perfect Richard.

(To Robert Falconbridge) Sirrah, speak: 90

What doth move you to claim your brother’s land?

BASTARD

Because he hath a half-face like my father!

With half that face would he have all my land,

A half-faced groat five hundred pound a year.

FALCONBRIDGE

My gracious liege, when that my father lived, 95

Your brother did employ my father much—

BASTARD

Well, sir, by this you cannot get my land.

Your tale must be how he employed my mother.

FALCONBRIDGE

And once dispatched him in an embassy

To Germany, there with the Emperor

To treat of high affairs touching that time.

Th‘advantage of his absence took the King,

And in the meantime sojourned at my father’s,

Where how he did prevail I shame to speak.

But truth is truth:large lengths of seas and shores

Between my father and my mother lay, 106

As I have heard my father speak himself,

When this same lusty gentleman was got.

Upon his deathbed he by will bequeathed

His lands to me, and took it on his death 110

That this my mother’s son was none of his;

And if he were, he came into the world

Full fourteen weeks before the course of time.

Then, good my liege, let me have what is mine,

My father’s land, as was my father’s will. 115

KING JOHN

Sirrah, your brother is legitimate.

Your father’s wife did after wedlock bear him,

And if she did play false, the fault was hers,

Which fault lies on the hazards of all husbands

That marry wives. Tell me, how if my brother,

Who, as you say, took pains to get this son,

Had of your father claimed this son for his ?

In sooth, good friend, your father might have kept

This calf, bred from his cow, from all the world;

In sooth he might. Then if he were my brother’s, 125

My brother might not claim him, nor your father,

Being none of his, refuse him. This concludes:

My mother’s son did get your father’s heir;

Your father’s heir must have your father’s land.

FALCONBRIDGE

Shall then my father’s will be of no force 130

To dispossess that child which is not his?

BASTARD

Of no more force to dispossess me, sir,

Than was his will to get me, as I think.

QUEEN ELEANOR

Whether hadst thou rather be: a Falconbridge,

And like thy brother to enjoy thy land, 135

Or the reputed son of Cœur-de-lion,

Lord of thy presence, and no land beside?

BASTARD

Madam, an if my brother had my shape,

And I had his, Sir Robert’s his like him,

And if my legs were two such riding-rods, 140

My arms such eel-skins stuffed, my face so thin

That in mine ear I durst not stick a rose

Lest men should say ‘Look where three-farthings

goes!’,

And, to his shape, were heir to all this land,

Would I might never stir from off this place.

I would give it every foot to have this face;

It would not be Sir Nob in any case.

QUEEN ELEANOR

I like thee well. Wilt thou forsake thy fortune,

Bequeath thy land to him, and follow me?

I am a soldier and now bound to France. 150

BASTARD

Brother, take you my land; I’ll take my chance.

Your face hath got five hundred pound a year,

Yet sell your face for fivepence and ’tis dear.—

Madam, I’ll follow you unto the death.

QUEEN ELEANOR

Nay, I would have you go before me thither. 155

BASTARD

Our country manners give our betters way.

KING JOHN What is thy name?

BASTARD

Philip, my liege, so is my name begun:

Philip, good old Sir Robert’s wife’s eldest son,

KING JOHN

From henceforth bear his name whose form thou

bear’st. 160

Kneel thou down Philip, but arise more great:

He knights the Bastard

Arise Sir Richard and Plantagenet.

BASTARD

Brother by th’ mother’s side, give me your hand.

My father gave me honour, yours gave land.

Now blessèd be the hour, by night or day, 165

When I was got, Sir Robert was away.

QUEEN ELEANOR

The very spirit of Plantagenet I

I am thy grandam, Richard; call me so.

BASTARD

Madam, by chance, but not by truth; what though?

Something about, a little from the right,

In at the window, or else o‘er the hatch;

Who dares not stir by day must walk by night,

And have is have, however men do catch.

Near or far off, well won is still well shot,

And I am I, howe’er I was begot.

KING JOHN

Go, Falconbridge, now hast thou thy desire:

A landless knight makes thee a landed squire.—

Come, madam, and come, Richard; we must speed

For France; for France, for it is more than need.

BASTARD

Brother, adieu. Good fortune come to thee, 180

For thou wast got i’th’ way of honesty.

Exeunt all but the Bastard

A foot of honour better than I was,

But many a many foot of land the worse.

Well, now can I make any Joan a lady.

‘Good e’en, Sir Richard‘—’God-a-mercy fellow’;

And if his name be George I’ll call him Peter,

For new-made honour doth forget men’s names;

’Tis too respective and too sociable

For your conversion. Now your traveller,

He and his toothpick at my worship’s mess; 190

And when my knightly stomach is sufficed,

Why then I suck my teeth and catechize

My picked man of countries. ‘My dear sir,’

Thus leaning on mine elbow I begin,

‘I shall beseech you—’. That is Question now; 195

And then comes Answer like an Absey book.

‘O sir,’ says Answer, ‘at your best command,

At your employment, at your service, sir.’

‘No sir,’ says Question, ‘I, sweet sir, at yours.’

And so, ere Answer knows what Question would,

Saving in dialogue of compliment,

And talking of the Alps and Apennines,

The Pyrenean and the River Po,

It draws toward supper in conclusion so.

But this is worshipful society, 205

And fits the mounting spirit like myself;

For he is but a bastard to the time

That doth not smack of observation;

And so am I—whether I smack or no,

And not alone in habit and device, 210

Exterior form, outward accoutrement,

But from the inward motion—to deliver

Sweet, sweet, sweet poison for the age’s tooth;

Which, though I will not practise to deceive,

Yet to avoid deceit I mean to learn; 215

For it shall strew the footsteps of my rising.

Enter Lady Falconbridge and James Gurney

But who comes in such haste in riding-robes?

What woman-post is this? Hath she no husband

That will take pains to blow a horn before her?

O me, ’tis my mother! How now, good lady? 220

What brings you here to court so hastily?

LADY FALCONBRIDGE

Where is that slave thy brother? Where is he

That holds in chase mine honour up and down?

BASTARD

My brother Robert, old Sir Robert’s son?

Colbrand the Giant, that same mighty man? 225

Is it Sir Robert’s son that you seek so?

LADY FALCONBRIDGE

Sir Robert’s son, ay, thou unreverent boy,

Sir Robert’s son. Why scorn’st thou at Sir Robert?

He is Sir Robert’s son, and so art thou.

BASTARD

James Gurney, wilt thou give us leave awhile? 230

GURNEY

Good leave, good Philip.

BASTARD Philip Sparrow, James!

There’s toys abroad; anon I’ll tell thee more.

Exit James Gurney

Madam, I was not old Sir Robert’s son.

Sir Robert might have eat his part in me

Upon Good Friday, and ne’er broke his fast. 235

Sir Robert could do well, marry to confess,

Could a get me! Sir Robert could not do it:

We know his handiwork. Therefore, good mother,

To whom am I beholden for these limbs?

Sir Robert never holp to make this leg. 240

LADY FALCONBRIDGE

Hast thou conspired with thy brother too,

That for thine own gain shouldst defend mine honour?

What means this scorn, thou most untoward knave?

BASTARD

Knight, knight, good mother, Basilisco-like!

What! I am dubbed; I have it on my shoulder. 245

But, mother, I am not Sir Robert’s son.

I have disclaimed Sir Robert; and my land,

Legitimation, name, and all is gone.

Then, good my mother, let me know my father;

Some proper man, I hope; who was it, mother? 250

LADY FALCONBRIDGE

Hast thou denied thyself a Falconbridge ?

BASTARD

As faithfully as I deny the devil.

LADY FALCONBRIDGE

King Richard Cœur-de-lion was thy father.

By long and vehement suit I was seduced

To make room for him in my husband’s bed. 255

Heaven lay not my transgression to my charge!

Thou art the issue of my dear offence,

Which was so strongly urged past my defence.

BASTARD

Now by this light, were I to get again,

Madam, I would not wish a better father. 260

Some sins do bear their privilege on earth,

And so doth yours; your fault was not your folly.

Needs must you lay your heart at his dispose,

Subjected tribute to commanding love,

Against whose fury and unmatched force 265

The aweless lion could not wage the fight,

Nor keep his princely heart from Richard’s hand.

He that perforce robs lions of their hearts

May easily win a woman’s. Ay, my mother,

With all my heart I thank thee for my father. 270

Who lives and dares but say thou didst not well

When I was got, I’ll send his soul to hell.

Come, lady, I will show thee to my kin,

And they shall say, when Richard me begot,

If thou hadst said him nay, it had been sin. 275

Who says it was, he lies: I say ’twas not. Exeunt