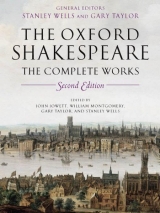

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

5.1 Enter Biondello, Lucentio, and Bianca. Gremio is out before

BIONDELLO Softly and swiftly, sir, for the priest is ready.

LUCENTIO I fly, Biondello; but they may chance to need thee at home, therefore leave us.

BIONDELLO Nay, faith, I’ll see the church a’ your back and then come back to my master’s as soon as I can.

Exeunt Lucentio, Bianca, and Biondello

GREMIO

I marvel Cambio comes not all this while.

Enter Petruccio, Katherine, Vincentio, Grumio, with attendants

PETRUCCIO

Sir, here’s the door. This is Lucentio’s house.

My father’s bears more toward the market-place.

Thither must I, and here I leave you, sir.

VINCENTIO

You shall not choose but drink before you go.

I think I shall command your welcome here,

And by all likelihood some cheer is toward.

He knocks

GREMIO They’re busy within. You were best knock louder.

Vincentio knocks again. The Pedant looks out of the window

PEDANT What’s he that knocks as he would beat down the gate?

VINCENTIO Is Signor Lucentio within, sir?

PEDANT He’s within, sir, but not to be spoken withal.

VINCENTIO What if a man bring him a hundred pound or two to make merry withal?

PEDANT Keep your hundred pounds to yourself. He shall need none so long as I live.

PETRUCCIO (to Vincentio) Nay, I told you your son was well beloved in Padua. (To the Pedant) Do you hear, sir, to leave frivolous circumstances, I pray you tell Signor Lucentio that his father is come from Pisa and is here at the door to speak with him.

PEDANT Thou liest. His father is come from Padua and here looking out at the window.

VINCENTIO Art thou his father?

PEDANT Ay, sir, so his mother says, if I may believe her.

PETRUCCIO (to Vincentio) Why, how now, gentleman?Why, this is flat knavery, to take upon you another man’s name.

PEDANT Lay hands on the villain. I believe a means to cozen somebody in this city under my countenance.

Enter Biondello

BIONDELLO (aside) I have seen them in the church together, God send ’em good shipping. But who is here? Mine old master, Vincentio—now we are undone and brought to nothing.

VINCENTIO (to Biondello) Come hither, crackhemp.

BIONDELLO I hope I may choose, sir.

VINCENTIO Come hither, you rogue. What, have you forgot me?

BIONDELLO Forgot you? No, sir, I could not forget you, for I never saw you before in all my life.

VINCENTIO What, you notorious villain, didst thou never see thy master’s father, Vincentio?

BIONDELLO What, my old worshipful old master? Yes, marry, sir, see where he looks out of the window.

VINCENTIO Is’t so indeed?

He beats Biondello

BIONDELLO Help, help, help! Here’s a madman will murder me.

Exit

PEDANT Help, son! Help, Signor Baptista!

Exit above

PETRUCCIO Prithee, Kate, let’s stand aside and see the end of this controversy.

They stand aside.

Enter Pedant with servants, Baptista, Tranio as Lucentio

TRANIO (to Vincentio) Sir, what are you that offer to beat my servant?

VINCENTIO What am I, sir? Nay, what are you, sir? O immortal gods, O fine villain, a silken doublet, a velvet hose, a scarlet cloak, and a copintank hat—O, I am undone, I am undone! While I play the good husband at home, my son and my servant spend all at the university.

TRANIO How now, what’s the matter?

BAPTISTA What, is the man lunatic?

TRANIO Sir, you seem a sober, ancient gentleman by your habit, but your words show you a madman. Why sir, what ‘cerns it you if I wear pearl and gold? I thank my good father, I am able to maintain it.

VINCENTIO Thy father! O villain, he is a sailmaker in Bergamo.

BAPTISTA You mistake, sir, you mistake, sir. Pray what do you think is his name?

VINCENTIO His name? As if I knew not his name—I have brought him up ever since he was three years old, and his name is Tranio.

PEDANT Away, away, mad ass. His name is Lucentio, and he is mine only son, and heir to the lands of me, Signor Vincentio.

VINCENTIO Lucentio? O, he hath murdered his master! Lay hold on him, I charge you, in the Duke’s name. O my son, my son! Tell me, thou villain, where is my son Lucentio?

TRANIO Call forth an officer.

Enter an Officer

Carry this mad knave to the jail. Father Baptista, I

charge you see that he be forthcoming.

VINCENTIO Carry me to the jail?

GREMIO Stay, officer, he shall not go to prison.

BAPTISTA Talk not, Signor Gremio. I say he shall go to prison.

GREMIO Take heed, Signor Baptista, lest you be cony-catched in this business. I dare swear this is the right Vincentio.

PEDANT Swear if thou dar’st.

GREMIO Nay, I dare not swear it.

TRANIO Then thou wert best say that I am not Lucentio.

GREMIO Yes, I know thee to be Signor Lucentio.

BAPTISTA Away with the dotard. To the jail with him.

Enter Biondello, Lucentio, and Bianca

VINCENTIO Thus strangers may be haled and abused. O monstrous villain!

BIONDELLO O, we are spoiled and—yonder he is. Deny him, forswear him, or else we are all undone.

Exeunt Biondello, Tranio, and Pedant, as fast as may be

LUCENTIO (to Vincentio) Pardon, sweet father.

He kneels

VINCENTIO Lives my sweet son?

BIANCA (to Baptista) Pardon, dear father.

BAPTISTA

How hast thou offended? Where is Lucentio?

LUCENTIO

Here’s Lucentio, right son to the right Vincentio,

That have by marriage made thy daughter mine,

While counterfeit supposes bleared thine eyne.

GREMIO

Here’s packing with a witness, to deceive us all.

VINCENTIO

Where is that damned villain Tranio,

That faced and braved me in this matter so?

BAPTISTA

Why, tell me, is not this my Cambio?

BIANCA

Cambio is changed into Lucentio.

LUCENTIO

Love wrought these miracles. Bianca’s love

Made me exchange my state with Tranio

While he did bear my countenance in the town,

And happily I have arrived at the last

Unto the wished haven of my bliss.

What Tranio did, myself enforced him to.

Then pardon him, sweet father, for my sake.

VINCENTIO I’ll slit the villain’s nose that would have sent me to the jail.

BAPTISTA But do you hear, sir, have you married my daughter without asking my good will? 125

VINCENTIO Fear not, Baptista. We will content you. Go to, but I will in to be revenged for this villainy.

Exit

BAPTISTA And I to sound the depth of this knavery. Exit

LUCENTIO Look not pale, Bianca. Thy father will not frown.

Exeunt Lucentio and Bianca

GREMIO

My cake is dough, but I’ll in among the rest,

Out of hope of all but my share of the feast.

Exit

KATHERINE (coming forward) Husband, let’s follow to see the end of this ado.

PETRUCCIO First kiss me, Kate, and we will.

KATHERINE What, in the midst of the street?

PETRUCCIO What, art thou ashamed of me?

KATHERINE No, sir, God forbid; but ashamed to kiss.

PETRUCCIO

Why then, let’s home again. Come sirrah, let’s away.

KATHERINE

Nay, I will give thee a kiss. Now pray thee love, stay. They kiss

PETRUCCIO

Is not this well? Come, my sweet Kate.

Better once than never, for never too late.

Exeunt

5.2 Enter Baptista, Vincentio, Gremio, the Pedant, Lucentio and Bianca, Petruccio, Katherine, and Hortensio, Tranio, Biondello, Grumio, and the Widow, the servingmen with Tranio bringing in a banquet

LUCENTIO

At last, though long, our jarring notes agree,

And time it is when raging war is done

To smile at scapes and perils overblown.

My fair Bianca, bid my father welcome,

While I with selfsame kindness welcome thine.

Brother Petruccio, sister Katherina,

And thou, Hortensio, with thy loving widow,

Feast with the best, and welcome to my house.

My banquet is to close our stomachs up

After our great good cheer. Pray you, sit down,

For now we sit to chat as well as eat.

They sit

PETRUCCIO

Nothing but sit, and sit, and eat, and eat.

BAPTISTA

Padua affords this kindness, son Petruccio.

PETRUCCIO

Padua affords nothing but what is kind.

HORTENSIO

For both our sakes I would that word were true. 15

PETRUCCIO

Now, for my life, Hortensio fears his widow.

WIDOW

Then never trust me if I be afeard.

PETRUCCIO

You are very sensible, and yet you miss my sense.

I mean Hortensio is afeard of you.

WIDOW

He that is giddy thinks the world turns round.

PETRUCCIO Roundly replied.

KATHERINE Mistress, how mean you that?

WIDOW Thus I conceive by him.

PETRUCCIO

Conceives by me! How likes Hortensio that?

HORTENSIO

My widow says thus she conceives her tale.

PETRUCCIO Very well mended. Kiss him for that, good widow.

KATHERINE

‘He that is giddy thinks the world turns round’—

I pray you tell me what you meant by that.

WIDOW

Your husband, being troubled with a shrew,

Measures my husband’s sorrow by his woe.

And now you know my meaning.

KATHERINE

A very mean meaning.

WIDOW

Right, I mean you.

KATHERINE

And I am mean indeed respecting you.

PETRUCCIO To her, Kate!

HORTENSIO To her, widow!

PETRUCCIO

A hundred marks my Kate does put her down.

HORTENSIO That’s my office.

PETRUCCIO

Spoke like an officer! Ha’ to thee, lad.

He drinks to Hortensio

BAPTISTA

How likes Gremio these quick-witted folks?

GREMIO

Believe me, sir, they butt together well.

BIANCA

Head and butt? An hasty-witted body

Would say your head and butt were head and horn.

VINCENTIO

Ay, mistress bride, hath that awakened you?

BIANCA

Ay, but not frighted me, therefore I’ll sleep again.

PETRUCCIO

Nay, that you shall not. Since you have begun,

Have at you for a better jest or two.

BIANCA

Am I your bird? I mean to shift my bush,

And then pursue me as you draw your bow.

You are welcome all.

Exit Bianca with Katherine and the Widow

PETRUCCIO

She hath prevented me here, Signor Tranio.

This bird you aimed at, though you hit her not.

Therefore a health to all that shot and missed.

TRANIO

O sir, Lucentio slipped me like his greyhound,

Which runs himself and catches for his master.

PETRUCCIO

A good swift simile, but something currish.

TRANIO

‘Tis well, sir, that you hunted for yourself.

’Tis thought your deer does hold you at a bay.

BAPTISTA

O, O, Petruccio, Tranio hits you now.

LUCENTIO

I thank thee for that gird, good Tranio.

HORTENSIO

Confess, confess, hath he not hit you here?

PETRUCCIO

A has a little galled me, I confess,

And as the jest did glance away from me,

‘Tis ten to one it maimed you two outright.

BAPTISTA

Now in good sadness, son Petruccio,

I think thou hast the veriest shrew of all.

PETRUCCIO

Well, I say no.—And therefore, Sir Assurance,

Let’s each one send unto his wife,

And he whose wife is most obedient

To come at first when he doth send for her

Shall win the wager which we will propose.

HORTENSIO Content. What’s the wager?

LUCFNTIO Twenty crowns.

PETRUCCIO Twenty crowns!

I’ll venture so much of my hawk or hound,

But twenty times so much upon my wife.

LUCENTIO A hundred, then.

HORTENSIO Content.

PETRUCCIO A match, ‘tis done.

HORTENSIO Who shall begin?

LUCENTIO That will I.

Go, Biondello, bid your mistress come to me.

BIONDELLO I go.

Exit

BAPTISTA

Son, I’ll be your half Bianca comes.

LUCENTIO

I’ll have no halves, I’ll bear it all myself.

Enter Biondello

How now, what news?

BIONDELLO

Sir, my mistress sends you word

That she is busy and she cannot come.

PETRUCCIO

How? She’s busy and she cannot come?

Is that an answer?

GREMlO Ay, and a kind one, too.

Pray God, sir, your wife send you not a worse.

PETRUCCIO

I hope, better.

HORTENSIO

Sirrah Biondello,

Go and entreat my wife to come to me forthwith.

Exit Biondello

PETRUCCIO

O ho, ‘entreat’ her—nay, then she must needs come.

HORTENSIO

I am afraid, sir, do what you can,

Enter Biondello

Yours will not be entreated. Now, where’s my wife?

BIONDELLO

She says you have some goodly jest in hand.

She will not come. She bids you come to her.

PETRUCCIO

Worse and worse! She will not come—O vile,

Intolerable, not to be endured!

Sirrah Grumio, go to your mistress.

Say I command her come to me.

Exit Grumio

HORTENSIO

I know her answer.

PETRUCCIO

What?

HORTENSIO

She will not.

PETRUCCIO

The fouler fortune mine, and there an end.

Enter Katherine

BAPTISTA

Now by my halidom, here comes Katherina.

KATHERINE (to Petruccio)

What is your will, sir, that you send for me?

PETRUCCIO

Where is your sister and Hortensio’s wife?

KATHERINE

They sit conferring by the parlour fire.

PETRUCCIO

Go, fetch them hither. If they deny to come,

Swinge me them soundly forth unto their husbands.

Away, I say, and bring them hither straight.

Exit Katherine

LUCENTIO

Here is a wonder, if you talk of wonders.

HORTENSIO

And so it is. I wonder what it bodes.

PETRUCCIO

Marry, peace it bodes, and love, and quiet life;

An aweful rule and right supremacy,

And, to be short, what not that’s sweet and happy.

BAPTISTA

Now fair befall thee, good Petruccio,

The wager thou hast won, and I will add

Unto their losses twenty thousand crowns,

Another dowry to another daughter,

For she is changed as she had never been.

PETRUCCIO

Nay, I will win my wager better yet,

And show more sign of her obedience,

Her new-built virtue and obedience.

Enter Katherine, Bianca, and the Widow

See where she comes, and brings your froward wives

As prisoners to her womanly persuasion.

Katherine, that cap of yours becomes you not.

Off with that bauble, throw it underfoot.

Katherine throws down her cap

WIDOW

Lord, let me never have a cause to sigh

Till I be brought to such a silly pass.

BIANCA

Fie, what a foolish duty call you this?

LUCENTIO

I would your duty were as foolish, too.

The wisdom of your duty, fair Bianca,

Hath cost me a hundred crowns since supper-time.

BIANCA

The more fool you for laying on my duty.

PETRUCCIO

Katherine, I charge thee tell these headstrong women

What duty they do owe their lords and husbands.

WIDOW

Come, come, you’re mocking. We will have no telling.

PETRUCCIO

Come on, I say, and first begin with her.

WIDOW She shall not.

PETRUCCIO

I say she shall: and first begin with her.

KATHERINE

Fie, fie, unknit that threat’ning, unkind brow,

And dart not scornful glances from those eyes

To wound thy lord, thy king, thy governor.

It blots thy beauty as frosts do bite the meads,

Confounds thy fame as whirlwinds shake fair buds,

And in no sense is meet or amiable.

A woman moved is like a fountain troubled,

Muddy, ill-seeming, thick, bereft of beauty,

And while it is so, none so dry or thirsty

Will deign to sip or touch one drop of it.

Thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper,

Thy head, thy sovereign, one that cares for thee,

And for thy maintenance commits his body

To painful labour both by sea and land,

To watch the night in storms, the day in cold,

Whilst thou liest warm at home, secure and safe,

And craves no other tribute at thy hands

But love, fair looks, and true obedience,

Too little payment for so great a debt.

Such duty as the subject owes the prince,

Even such a woman oweth to her husband,

And when she is froward, peevish, sullen, sour,

And not obedient to his honest will,

What is she but a foul contending rebel,

And graceless traitor to her loving lord?

I am ashamed that women are so simple

To offer war where they should kneel for peace,

Or seek for rule, supremacy, and sway

When they are bound to serve, love, and obey.

Why are our bodies soft, and weak, and smooth,

Unapt to toil and trouble in the world,

But that our soft conditions and our hearts

Should well agree with our external parts?

Come, come, you froward and unable worms,

My mind hath been as big as one of yours,

My heart as great, my reason haply more,

To bandy word for word and frown for frown;

But now I see our lances are but straws,

Our strength as weak, our weakness past compare,

That seeming to be most which we indeed least are.

Then vail your stomachs, for it is no boot,

And place your hands below your husband’s foot,

In token of which duty, if he please,

My hand is ready, may it do him ease.

PETRUCCIO

Why, there’s a wench! Come on, and kiss me, Kate.

They kiss

LUCENTIO

Well, go thy ways, old lad, for thou shalt ha’t.

VINCENTIO

‘Tis a good hearing when children are toward.

LUCENTIO

But a harsh hearing when women are froward.

PETRUCCIO Come, Kate, we’ll to bed.

We three are married, but you two are sped.

’Twas I won the wager, though (to Lucentio) you hit

the white,

And being a winner, God give you good night.

Exit Petruccio with Katherine

HORTENSIO

Now go thy ways, thou hast tamed a curst shrew.

LUCENTIO

’Tis a wonder, by your leave, she will be tamed so.

Exeunt

ADDITIONAL PASSAGES

The Taming of A Shrew, printed in 1594 and believed to derive from Shakespeare’s play as performed, contains episodes continuing and rounding off the Christopher Sly framework which may echo passages written by Shakespeare but not printed in the Folio. They are given below.

A. The following exchange occurs at a point for which there is no exact equivalent in Shakespeare’s play. It could come at the end of 2.1.The ‘fool’ of the first line is Sander, the counterpart of Grumio.

Then Sly speaks

SLY Sim, when will the fool come again?

LORD He’ll come again, my lord, anon.

SLY Gi’s some more drink here. Zounds, where’s the tapster? Here, Sim, eat some of these things.

LORD So I do, my lord.

SLY Here, Sim, I drink to thee.

LORD My lord, here comes the players again.

SLY O brave, here’s two fine gentlewomen.

B. This passage comes between 4.5 and 4.6. If it originates with Shakespeare it implies that Grumio accompanies Petruccio at the beginning of 4.6.

SLY Sim, must they be married now?

LORD Ay, my lord.

Enter Ferando and Kate and Sander

SLY Look, Sim, the fool is come again now.

C. Sly interrupts the action of the play-within-play. This is at 5.1.102 of Shakespeare’s play.

Phylotus and Valeria runs away.

Then Sly speaks

SLY I say we’ll have no sending to prison.

LORD My lord, this is but the play. They’re but in jest.

SLY I tell thee, Sim, we’ll have no sending to prison, that’s flat. Why, Sim, am not I Don Christo Vary? Therefore I say they shall not go to prison.

LORD No more they shall not, my lord. They be run away.

SLY Are they run away, Sim? That’s well. Then gi’s some more drink, and let them play again.

LORD Here, my lord.

Sly drinks and then falls asleep

D. Sly is carried off between 5.1 and 5.2.

Exeunt omnes

Sly sleeps

LORD

Who’s within there? Come hither, sirs, my lord’s

Asleep again. Go take him easily up

And put him in his own apparel again,

And lay him in the place where we did find him

Just underneath the alehouse side below.

But see you wake him not in any case.

BOY

It shall be done, my lord. Come help to bear him hence.

Exit

E. The conclusion.

Then enter two bearing of Sly in his own apparel again and leaves him where they found him and then goes out. Then enter the Tapster

TAPSTER

Now that the darksome night is overpast

And dawning day appears in crystal sky,

Now must I haste abroad. But soft, who’s this?

What, Sly! O wondrous, hath he lain here all night?

I’ll wake him. I think he’s starved by this,

But that his belly was so stuffed with ale.

What ho, Sly, awake, for shame!

SLY Sim, gi’s some more wine. What, ’s all the players gone? Am not I a lord?

TAPSTER

A lord with a murrain! Come, art thou drunken still?

SLY

Who’s this? Tapster? O Lord, sirrah, I have had

The bravest dream tonight that ever thou

Heardest in all thy life.

TAPSTER

Ay, marry, but you had best get you home,

For your wife will course you for dreaming here tonight.

SLY

Will she? I know now how to tame a shrew.

I dreamt upon it all this night till now,

And thou hast waked me out of the best dream

That ever I had in my life. But I’ll to my

Wife presently and tame her too,

An if she anger me.

TAPSTER

Nay, tarry, Sly, for I’ll go home with thee

And hear the rest that thou hast dreamt tonight.

Exeunt omnes

THE FIRST PART OF THE CONTENTION

(2 HENRY VI)

WHEN Shakespeare’s history plays were gathered together in the 1623 Folio, seven years after he died, they were printed in the order of their historical events, each with a title naming the king in whose reign those events occurred. No one supposes that this is the order in which Shakespeare wrote them; and the Folio titles are demonstrably not, in all cases, those by which the plays were originally known. The three concerned with the reign of Henry VI are listed in the Folio, simply and unappealingly, as the First, Second, and Third Parts of King Henry the Sixth, and these are the names by which they have continued to be known. Versions of the Second and Third had appeared long before the Folio, in 1594 and 1595; their head titles read The First Part of the Contention of the two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster with the Death of the Good Duke Humphrey and The True Tragedy of Richard, Duke of York, and the Good King Henry the Sixth. These are, presumably, full versions of the plays’ original titles, and we revert to them in preference to the Folio’s historical listing.

A variety of internal evidence suggests that the Folio’s Part One was composed after The First Part of the Contention and Richard, Duke of York, so we depart from the Folio order, though a reader wishing to read the plays in their narrative sequence will read Henry VI, Part One before the other two plays. The dates of all three are uncertain, but Part One is alluded to in 1592, when it was probably new. The First Part of the Contention probably belongs to 1590-1.

The play draws extensively on English chronicle history for its portrayal of the troubled state of England under Henry VI (1421-71). It dramatizes the touchingly weak King’s powerlessness against the machinations of his nobles, especially Richard, Duke of York, himself ambitious for the throne. Richard engineers the Kentish rebellion, led by Jack Cade, which provides some of the play’s liveliest episodes; and at the play’s end Richard seems poised to take the throne.

Historical events of ten years (11445-55) are dramatized with comparative fidelity within a coherent structure that offers a wide variety of theatrical entertainment. Though the play employs old-fashioned conventions of language (particularly the recurrent classical references) and of dramaturgy (such as the horrors of severed heads), its bold characterization, its fundamentally serious but often ironically comic presentation of moral and political issues, the powerful rhetoric of its verse, and the vivid immediacy of its prose have proved highly effective in its rare modern revivals.

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

Of the King’s Party

KING HENRY VI

QUEEN MARGARET

William de la Pole, Marquis, later Duke, of SUFFOLK, the Queen’s lover

Duke Humphrey of GLOUCESTER, the Lord Protector, the King’s uncle

Dame Eleanor Cobham, the DUCHESS of Gloucester

CARDINAL BEAUFORT, Bishop of Winchester, Gloucester’s uncle and the King’s great-uncle

Duke of BUCKINGHAM

Duke of SOMERSET

Old Lord CLIFFORD

YOUNG CLIFFORD, his son

Of the Duke of York’s Party

Earl of SALISBURY

Earl of WARWICK, his son

The petitions and the combat

Two or three PETITIONERS

Thomas HORNER, an armourer

PETER Thump, his man

Three NEIGHBOURS, who drink to Horner

Three PRENTICES, who drink to Peter

The conjuration

Margery Jordan, a WITCH

Roger BOLINGBROKE, a conjurer

ASNATH, a spirit

The false miracle

Simon SIMPCOX

SIMPCOX’S WIFE

The MAYOR of Saint Albans

Aldermen of Saint Albans

A BEADLE of Saint Albans

Townsmen of Saint Albans

Eleanor’s penance

Gloucester’s SERVANTS

Two SHERIFFS of London

Sir John STANLEY

HERALD

The murder of Gloucester

Two MURDERERS

COMMONS

The murder of Suffolk

CAPTAIN of a ship

MASTER of that ship

The Master’s MATE

Walter WHITMORE

Two GENTLEMEN

The Cade Rebellion

Jack CADE, a Kentishman suborned by the Duke of York

Three or four CITIZENS of London

Alexander IDEN, an esquire of Kent, who kills Cade

Others

VAUX, a messenger

APOST

MESSENGERS

A SOLDIER

Attendants, guards, servants, soldiers, falconers