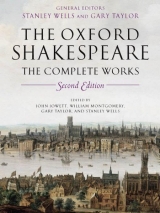

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 71 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

5.6 ⌈Flourish.⌉ Enter King Henry and the Duke of York, ⌈with other lords and attendants⌉

KING HENRY

Kind uncle York, the latest news we hear

Is that the rebels have consumed with fire

Our town of Ci’cester in Gloucestershire;

But whether they be ta’en or slain we hear not.

Enter the Earl of Northumberland

Welcome, my lord. What is the news?

NORTHUMBERLAND

First, to thy sacred state wish I all happiness.

The next news is, I have to London sent

The heads of Salisbury, Spencer, Blunt, and Kent.

The manner of their taking may appear

At large discoursed in this paper here.

He gives the paper to King Henry

KING HENRY

We thank thee, gentle Percy, for thy pains,

And to thy worth will add right worthy gains.

Enter Lord Fitzwalter

FITZWALTER

My lord, I have from Oxford sent to London

The heads of Brocas and Sir Bennet Seely,

Two of the dangerous consorted traitors

That sought at Oxford thy dire overthrow.

KING HENRY

Thy pains, Fitzwalter, shall not be forgot.

Right noble is thy merit, well I wot.

Enter Harry Percy, with the Bishop of Carlisle, guarded

HARRY PERCY

The grand conspirator Abbot of Westminster,

With clog of conscience and sour melancholy,

Hath yielded up his body to the grave.

But here is Carlisle living, to abide

Thy kingly doom and sentence of his pride.

KING HENRY Carlisle, this is your doom.

Choose out some secret place, some reverent room

More than thou hast, and with it joy thy life.

So as thou liv’st in peace, die free from strife.

For though mine enemy thou hast ever been,

High sparks of honour in thee have I seen.

Enter Exton with ⌈his men bearing⌉ the coffin

EXTON

Great King, within this coffin I present

Thy buried fear. Herein all breathless lies

The mightiest of thy greatest enemies,

Richard of Bordeaux, by me hither brought.

KING HENRY

Exton, I thank thee not, for thou hast wrought

A deed of slander with thy fatal hand

Upon my head and all this famous land.

EXTON

From your own mouth, my lord, did I this deed.

KING HENRY

They love not poison that do poison need;

Nor do I thee. Though I did wish him dead,

I hate the murderer, love him murdered.

The guilt of conscience take thou for thy labour,

But neither my good word nor princely favour.

With Cain go wander through the shades of night,

And never show thy head by day nor light.

⌈Exeunt Exton and his men⌉

Lords, I protest my soul is full of woe

That blood should sprinkle me to make me grow.

Come mourn with me for what I do lament,

And put on sullen black incontinent.

I’ll make a voyage to the Holy Land

To wash this blood off from my guilty hand.

March sadly after. Grace my mournings here

In weeping after this untimely bier.

Exeunt ⌈With the coffin⌉

ADDITIONAL PASSAGES

The following passages of four lines or more appear in the 1597 Quarto but not the Folio; Shakespeare probably deleted them as part of his limited revisions to the text.

a. . AFTER 1.3.127

And for we think the eagle-winged pride

Of sky-aspiring and ambitious thoughts

With rival-hating envy set on you

To wake our peace, which in our country’s cradle

Draws the sweet infant breath of gentle sleep,

b. AFTER 1.3.235

O, had’t been a stranger, not my child,

To smooth his fault I should have been more mild.

A partial slander sought I to avoid,

And in the sentence my own life destroyed.

c. AFTER 1.3.256

BOLINGBROKE

Nay, rather every tedious stride I make

Will but remember what a deal of world

I wander from the jewels that I love.

Must I not serve a long apprenticehood

To foreign passages, and in the end,

Having my freedom, boast of nothing else

But that I was a journeyman to grief?

JOHN OF GAUNT

All places that the eye of heaven visits

Are to a wise man ports and happy havens.

Teach thy necessity to reason thus:

There is no virtue like necessity.

Think not the King did banish thee,

But thou the King. Woe doth the heavier sit

Where it perceives it is but faintly borne.

Go, say I sent thee forth to purchase honour,

And not the King exiled thee; or suppose

Devouring pestilence hangs in our air

And thou art flying to a fresher clime.

Look what thy soul holds dear, imagine it

To lie that way thou goest, not whence thou com’st.

Suppose the singing birds musicians,

The grass whereon thou tread’st the presence strewed,

The flowers fair ladies, and thy steps no more

Than a delightful measure or a dance;

For gnarling sorrow hath less power to bite

The man that mocks at it and sets it light.

d. AFTER 3.2.28

The means that heavens yield must be embraced

And not neglected; else heaven would,

And we will not: heaven’s offer we refuse,

The proffered means of succour and redress.

e. AFTER 4.1.50

ANOTHER LORD

I task the earth to the like, forsworn Aumerle, And spur thee on with full as many lies As may be hollowed in thy treacherous ear From sun to sun. There is my honour’s pawn. Engage it to the trial if thou darest.

He throws down his gage

AUMERLE

Who sets me else? By heaven, I’ll throw at all. I have a thousand spirits in one breast To answer twenty thousand such as you.

ROMEO AND JULIET

ON its first appearance in print, in 1597, Romeo and Juliet was described as ‘An excellent conceited tragedy’ that had ‘been often (with great applause) played publicly’; its popularity is witnessed by the fact that this is a pirated version, put together from actors’ memories as a way of cashing in on its success. A second printing, two years later, offered a greatly superior text apparently printed from Shakespeare’s working papers. Probably he wrote it in 1594 or 1595.

The story was already well known, in Italian, French, and English. Shakespeare owes most to Arthur Brooke’s long poem The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562), which had already supplied hints for The Two Gentlemen of Verona; he may also have looked at some of the other versions. In his address ‘To the Reader’, Brooke says that he has seen ‘the same argument lately set forth on stage with more commendation than I can look for’, but no earlier play survives.

Shakespeare’s Prologue neatly sketches the plot of the two star-crossed lovers born of feuding families whose deaths ‘bury their parents’ strife’; and the formal verse structure of the Prologue—a sonnet—is matched by the carefully patterned layout of the action. At the climax of the first scene, Prince Escalus stills a brawl between representatives of the houses of Montague (Romeo’s family) and Capulet (Juliet’s); at the end of Act 3, Scene 1, he passes judgement on another, more serious brawl, banishing Romeo for killing Juliet’s cousin Tybalt after Tybalt had killed Romeo’s friend and the Prince’s kinsman, Mercutio; and at the end of Act 5, the Prince presides over the reconciliation of Montagues and Capulets. Within this framework of public life Romeo and Juliet act out their brief tragedy: in the first act, they meet and declare their love—in another sonnet; in the second, they arrange to marry in secret; in the third, after Romeo’s banishment, they consummate their marriage and part; in the fourth, Juliet drinks a sleeping draught prepared by Friar Laurence so that she may escape marriage to Paris and, after waking in the family tomb, run off with Romeo; in the fifth, after Romeo, believing her to be dead, has taken poison, she stabs herself to death.

The play’s structural formality is offset by an astonishing fertility of linguistic invention, showing itself no less in the comic bawdiness of the servants, the Nurse, and (on a more sophisticated level) Mercutio than in the rapt and impassioned poetry of the lovers. Shakespeare’s mastery over a wide range of verbal styles combines with his psychological perceptiveness to create a richer gallery of memorable characters than in any play written up to this time; and his theatrical imagination compresses Brooke’s leisurely narrative into a dramatic masterpiece.

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

CHORUS

ROMEO

MONTAGUE, his father

MONTAGUE’S WIFE

BENVOLIO, Montague’s nephew

ABRAHAM, Montague’s servingman

BALTHASAR, Romeo’s man

JULIET

CAPULET, her father

CAPULET’S WIFE

TYBALT, her nephew

His page

PETRUCCIO

CAPULET’S COUSIN

Juliet’s NURSE

Other SERVINGMEN

MUSICIANS

Escalus, PRINCE of Verona

FRIAR LAURENCE

FRIAR JOHN

An APOTHECARY

CHIEF WATCHMAN

Other CITIZENS OF THE WATCH

Masquers, guests, gentlewomen, followers of the Montague and Capulet factions

The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet

Prologue Enter Chorus

CHORUS

Two households, both alike in dignity

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life,

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The fearful passage of their death-marked love

And the continuance of their parents’ rage—

Which but their children’s end, naught could remove—

Is now the two-hours’ traffic of our stage;

The which if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

Exit

1.1 Enter Samson and Gregory, of the house of Capulet, with swords and bucklers

SAMSON Gregory, on my word, we’ll not carry coals.

GREGORY No, for then we should be colliers.

SAMSON I mean an we be in choler, we’ll draw.

GREGORY Ay, while you live, draw your neck out of collar.

SAMSON I strike quickly, being moved.

GREGORY But thou art not quickly moved to strike.

SAMSON A dog of the house of Montague moves me.

GREGORY To move is to stir, and to be valiant is to stand, therefore if thou art moved, thou runn’st away.

SAMSON A dog of that house shall move me to stand. I will take the wall of any man or maid of Montague’s.

GREGORY That shows thee a weak slave, for the weakest goes to the wall.

SAMSON ’Tis true, and therefore women, being the weaker vessels, are ever thrust to the wall; therefore I will push Montague’s men from the wall, and thrust his maids to the wall.

GREGORY The quarrel is between our masters and us their men.

SAMSON ’Tis all one. I will show myself a tyrant: when I have fought with the men I will be civil with the maids—I will cut off their heads.

GREGORY The heads of the maids?

SAMSON Ay, the heads of the maids, or their maidenheads, take it in what sense thou wilt.

GREGORY They must take it in sense that feel it.

SAMSON Me they shall feel while I am able to stand, and ’tis known I am a pretty piece of flesh.

GREGORY ’Tis well thou art not fish. If thou hadst, thou hadst been poor-john.

Enter Abraham and another servingman of the Montagues

Draw thy tool. Here comes of the house of Montagues.

SAMSON My naked weapon is out. Quarrel, I will back thee.

GREGORY How—turn thy back and run?

SAMSON Fear me not.

GREGORY No, marry—I fear thee!

SAMSON Let us take the law of our side. Let them begin.

GREGORY I will frown as I pass by, and let them take it as they list.

SAMSON Nay, as they dare. I will bite my thumb at them, which is disgrace to them if they bear it. He bites his thumb

ABRAHAM Do you bite your thumb at us, sir?

SAMSON I do bite my thumb, sir.

ABRAHAM Do you bite your thumb at us, sir?

SAMSON (to Gregory) Is the law of our side if I say ’Ay’ ?

GREGORY No.

SAMSON (to Abraham) No, sir, I do not bite my thumb at you, sir, but I bite my thumb, sir.

GREGORY (to Abraham) Do you quarrel, sir?

ABRAHAM Quarrel, sir? No, sir.

SAMSON But if you do, sir, I am for you. I serve as good a man as you.

ABRAHAM No better.

SAMSON Well, sir.

Enter Benvolio

GREGORY Say ‘better’. Here comes one of my master’s kinsmen.

SAMSON (to Abraham) Yes, better, sir.

ABRAHAM You lie.

SAMSON Draw, if you be men. Gregory, remember thy washing blow.

They draw and fight

BENVOLIO (drawing) Part, fools. Put up your swords. You know not what you do.

Enter Tybalt

TYBALT (drawing) What, art thou drawn among these heartless hinds? Turn thee, Benvolio. Look upon thy death.

BENVOLIO

I do but keep the peace. Put up thy sword,

Or manage it to part these men with me.

TYBALT

What, drawn and talk of peace? I hate the word

As I hate hell, all Montagues, and thee.

Have at thee, coward.

They fight. Enter three or four Citizens ⌈of the watch⌉, with clubs or partisans

⌈CITIZENS OF THE WATCH⌉

Clubs, bills and partisans! Strike! Beat them down!

Down with the Capulets. Down with the Montagues.

Enter Capulet in his gown, and his Wife

CAPULET

What noise is this? Give me my long sword, ho!

CAPULET’S WIFE

A crutch, a crutch—why call you for a sword?

Enter Montague ⌈With his sword drawn⌉, and his Wife

CAPULET

My sword, I say. Old Montague is come,

And flourishes his blade in spite of me.

MONTAGUE

Thou villain Capulet!

⌈His Wife holds him back⌉

Hold me not, let me go.

MONTAGUE’S WIFE

Thou shalt not stir one foot to seek a foe.

⌈The Citizens of the watch attempt to part the factions.⌉

Enter Prince Escalus with his train

PRINCE

Rebellious subjects, enemies to peace,

Profaners of this neighbour-stained steet—

Will they not hear? What ho, you men, you beasts,

That quench the fire of your pernicious rage

With purple fountains issuing from your veins:

On pain of torture, from those bloody hands

Throw your mistempered weapons to the ground,

And hear the sentence of your moved Prince.

⌈Montague, Capulet, and their followers throw down their weapons]

Three civil brawls bred of an airy word

By thee, old Capulet, and Montague,

Have thrice disturbed the quiet of our streets

And made Verona’s ancient citizens

Cast by their grave-beseeming ornaments

To wield old partisans in hands as old,

Cankered with peace, to part your cankered hate.

If ever you disturb our streets again

Your lives shall pay the forfeit of the peace.

For this time all the rest depart away.

You, Capulet, shall go along with me;

And Montague, come you this afternoon

To know our farther pleasure in this case

To old Freetown, our common judgement-place.

Once more, on pain of death, all men depart.

Exeunt all but Montague, his Wife, and Benvolio

MONTAGUE

Who set this ancient quarrel new abroach?

Speak, nephew: were you by when it began?

BENVOLIO

Here were the servants of your adversary

And yours, close fighting ere I did approach.

I drew to part them. In the instant came

The fiery Tybalt with his sword prepared,

Which, as he breathed defiance to my ears,

He swung about his head and cut the winds

Who, nothing hurt withal, hissed him in scorn.

While we were interchanging thrusts and blows,

Came more and more, and fought on part and part

Till the Prince came, who parted either part.

MONTAGUE’S WIFE

O where is Romeo—saw you him today?

Right glad I am he was not at this fray.

BENVOLIO

Madam, an hour before the worshipped sun

Peered forth the golden window of the east,

A troubled mind drive me to walk abroad,

Where, underneath the grove of sycamore

That westward rooteth from this city side,

So early walking did I see your son.

Towards him I made, but he was ware of me,

And stole into the covert of the wood.

I, measuring his affections by my own—

Which then most sought where most might not be

found,

Being one too many by my weary self—

Pursued my humour not pursuing his,

And gladly shunned who gladly fled from me.

MONTAGUE

Many a morning hath he there been seen,

With tears augmenting the fresh morning’s dew,

Adding to clouds more clouds with his deep sighs.

But all so soon as the all-cheering sun

Should in the farthest east begin to draw

The shady curtains from Aurora’s bed,

Away from light steals home my heavy son,

And private in his chamber pens himself,

Shuts up his windows, locks fair daylight out,

And makes himself an artificial night.

Black and portentous must this humour prove,

Unless good counsel may the cause remove.

BENVOLIO

My noble uncle, do you know the cause?

MONTAGUE

I neither know it nor can learn of him.

BENVOLIO

Have you importuned him by any means?

MONTAGUE

Both by myself and many other friends,

But he, his own affection’s counsellor,

Is to himself—I will not say how true,

But to himself so secret and so close,

So far from sounding and discovery,

As is the bud bit with an envious worm

Ere he can spread his sweet leaves to the air

Or dedicate his beauty to the sun.

Could we but learn from whence his sorrows grow

We would as willingly give cure as know.

Enter Romeo

BENVOLIO

See where he comes. So please you step aside,

I’ll know his grievance or be much denied.

MONTAGUE

I would thou wert so happy by thy stay

To hear true shrift. Come, madam, let’s away.

Exeunt Montague and his Wife

BENVOLIO

Good morrow, cousin.

ROMEO Is the day so young?

BENVOLIO

But new struck nine.

ROMEO Ay me, sad hours seem long.

Was that my father that went hence so fast?

BENVOLIO

It was. What sadness lengthens Romeo’s hours?

ROMEO

Not having that which, having, makes them short.

BENVOLIO In love.

ROMEO Out.

BENVOLIO Of love?

ROMEO

Out of her favour where I am in love.

BENVOLIO

Alas that love, so gentle in his view,

Should be so tyrannous and rough in proof.

ROMEO

Alas that love, whose view is muffled still,

Should without eyes see pathways to his will.

Where shall we dine? ⌈Seeing blood⌉ O me! What fray

was here?

Yet tell me not, for I have heard it all.

Here’s much to do with hate, but more with love.

Why then, O brawling love, O loving hate,

O anything of nothing first create;

O heavy lightness, serious vanity,

Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms,

Feather of lead, bright smoke, cold fire, sick health,

Still-waking sleep, that is not what it is I

This love feel I, that feel no love in this.

Dost thou not laugh?

BENVOLIO No, coz, I rather weep.

ROMEO

Good heart, at what?

BENVOLIO At thy good heart’s oppression.

ROMEO Why, such is love’s transgression.

Griefs of mine own lie heavy in my breast,

Which thou wilt propagate to have it pressed

With more of thine. This love that thou hast shown

Doth add more grief to too much of mine own.

Love is a smoke made with the fume of sighs,

Being purged, a fire sparkling in lovers’ eyes,

Being vexed, a sea nourished with lovers’ tears.

What is it else? A madness most discreet,

A choking gall and a preserving sweet.

Farewell, my coz.

BENVOLIO Soft, I will go along;

An if you leave me’so, you do me wrong.

ROMEO

Tut, I have lost myself. I am not here.

This is not Romeo; he’s some other where.

BENVOLIO

Tell me in sadness, who is that you love?

ROMEO What, shall I groan and tell thee?

BENVOLIO

Groan? Why no; but sadly tell me who.

ROMEO

Bid a sick man in sadness make his will,

A word ill urged to one that is so ill.

In sadness, cousin, I do love a woman.

BENVOLIO

I aimed so near when I supposed you loved.

ROMEO

A right good markman; and she’s fair I love.

BENVOLIO

A right fair mark, fair coz, is soonest hit.

ROMEO

Well, in that hit you miss. She’ll not be hit

With Cupid’s arrow; she hath Dian’s wit,

And, in strong proof of chastity well armed,

From love’s weak childish bow she lives unharmed.

She will not stay the siege of loving terms,

Nor bide th’encounter of assailing eyes,

Nor ope her lap to saint-seducing gold.

O, she is rich in beauty, only poor

That when she dies, with beauty dies her store.

BENVOLIO

Then she hath sworn that she will still live chaste?

ROMEO

She hath, and in that sparing makes huge waste;

For beauty starved with her severity

Cuts beauty off from all posterity.

She is too fair, too wise, wisely too fair,

To merit bliss by making me despair.

She hath forsworn to love, and in that vow

Do I live dead, that live to tell it now.

BENVOLIO

Be ruled by me; forget to think of her.

ROMEO

O, teach me how I should forget to think!

BENVOLIO

By giving liberty unto thine eyes.

Examine other beauties.

ROMEO ’Tis the way

To call hers, exquisite, in question more.

These happy masks that kiss fair ladies’ brows,

Being black, puts us in mind they hide the fair.

He that is strucken blind cannot forget

The precious treasure of his eyesight lost.

Show me a mistress that is passing fair,

What doth her beauty serve but as a note

Where I may read who passed that passing fair?

Farewell, thou canst not teach me to forget.

BENVOLIO

I’ll pay that doctrine, or else die in debt. Exeunt

1.2 Enter Capulet, Paris, and ⌈Peter,⌉ a servingman

CAPULET

But Montague is bound as well as I,

In penalty alike, and ’tis not hard, I think,

For men so old as we to keep the peace.

PARIS

Of honourable reckoning are you both,

And pity ’tis you lived at odds so long.

But now, my lord: what say you to my suit?

CAPULET

But saying o’er what I have said before.

My child is yet a stranger in the world;

She hath not seen the change of fourteen years.

Let two more summers wither in their pride

Ere we may think her ripe to be a bride.

PARIS

Younger than she are happy mothers made.

CAPULET

And too soon marred are those so early made.

But woo her, gentle Paris, get her heart;

My will to her consent is but a part,

And, she agreed, within her scope of choice

Lies my consent and fair-according voice.

This night I hold an old-accustomed feast

Whereto I have invited many a guest

Such as I love, and you among the store,

One more most welcome, makes my number more.

At my poor house look to behold this night

Earth-treading stars that make dark heaven light.

Such comfort as do lusty young men feel

When well-apparelled April on the heel

Of limping winter treads—even such delight

Among fresh female buds shall you this night

Inherit at my house; hear all, all see,

And like her most whose merit most shall be,

Which on more view of many, mine, being one,

May stand in number, though in reck’ning none.

Come, go with me. (Giving ⌈Peter⌉ a paper) Go, sirrah,

trudge about;

Through fair Verona find those persons out

Whose names are written there, and to them say

My house and welcome on their pleasure stay.

Exeunt Capulet and Paris

⌈PETER⌉ Find them out whose names are written here? It

is written that the shoemaker should meddle with his

yard and the tailor with his last, the fisher with his

pencil and the painter with his nets; but I am sent to

find those persons whose names are here writ, and can

never find what names the writing person hath here

writ. I must to the learned.

Enter Benvolio and Romeo

In good time.

BENVOLIO (to Romeo)

Tut, man, one fire burns out another’s burning,

One pain is lessened by another’s anguish.

Turn giddy, and be holp by backward turning.

One desperate grief cures with another’s languish.

Take thou some new infection to thy eye,

And the rank poison of the old will die.

ROMEO

Your plantain leaf is excellent for that.

BENVOLIO For what, I pray thee?

ROMEO For your broken shin.

BENVOLIO Why, Romeo, art thou mad?

ROMEO

Not mad, but bound more than a madman is;

Shut up in prison, kept without my food,

Whipped and tormented and—(to ⌈Peter⌉ Good e’en,

good fellow.

⌈PETER⌉

God gi‘good e’en. I pray, sir, can you read?

ROMEO

Ay, mine own fortune in my misery.

⌈PETER⌉ erhaps you have learned it without book. But I pray, can you read anything you see?

ROMEO

Ay, if I know the letters and the language.

⌈PETER⌉ Ye say honestly. Rest you merry.

ROMEO Stay, fellow, I can read.

He reads the letter

‘Signor Martino and his wife and daughters,

County Anselme and his beauteous sisters,

The lady widow of Vitruvio,

Signor Placentio and his lovely nieces,

Mercutio and his brother Valentine,

Mine uncle Capulet, his wife and daughters,

My fair niece Rosaline and Livia,

Signor Valentio and his cousin Tybalt,

Lucio and the lively Helena.’

A fair assembly. Whither should they come?

⌈PETER⌉ Up.

ROMEO Whither?

⌈PETER⌉ To supper to our house.

ROMEO Whose house?

⌈PETER⌉ My master’s.

ROMEO

Indeed, I should have asked thee that before.

⌈PETER⌉ Now I’ll tell you without asking. My master is

the great rich Capulet, and if you be not of the house

of Montagues, I pray come and crush a cup of wine.

Rest you merry. Exit

BENVOLIO

At this same ancient feast of Capulet’s

Sups the fair Rosaline, whom thou so loves,

With all the admirèd beauties of Verona.

Go thither, and with unattainted eye

Compare her face with some that I shall show,

And I will make thee think thy swan a crow.

ROMEO

When the devout religion of mine eye

Maintains such falsehood, then turn tears to fires;

And these who, often drowned, could never die,

Transparent heretics, be burnt for liars.

One fairer than my love !—the all-seeing sun

Ne’er saw her match since first the world begun.

BENVOLIO

Tut, you saw her fair, none else being by,

Herself poised with herself in either eye;

But in that crystal scales let there be weighed

Your lady’s love against some other maid

That I will show you shining at this feast,

And she shall scant show well that now seems best.

ROMEO

I’ll go along, no such sight to be shown,

But to rejoice in splendour of mine own. Exeunt