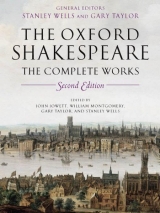

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 49 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

O yes, it may; thou hast no eyes to see,

But hatefully, at random dost thou hit.

Thy mark is feeble age; but thy false dart

Mistakes that aim, and cleaves an infant’s heart.

‘Hadst thou but bid beware, then he had spoke,

And, hearing him, thy power had lost his power.

The destinies will curse thee for this stroke.

They bid thee crop a weed; thou pluck’st a flower.

Love’s golden arrow at him should have fled,

And not death’s ebon dart to strike him dead.

‘Dost thou drink tears, that thou provok’st such weeping?

What may a heavy groan advantage thee?

Why hast thou cast into eternal sleeping

Those eyes that taught all other eyes to see?

Now nature cares not for thy mortal vigour,

Since her best work is ruined with thy rigour.’

Here overcome, as one full of despair,

She vailed her eyelids, who like sluices stopped

The crystal tide that from her two cheeks fair

In the sweet channel of her bosom dropped.

But through the flood-gates breaks the silver rain,

And with his strong course opens them again.

O, how her eyes and tears did lend and borrow!

Her eye seen in the tears, tears in her eye,

Both crystals, where they viewed each other’s sorrow:

Sorrow, that friendly sighs sought still to dry,

But, like a stormy day, now wind, now rain,

Sighs dry her cheeks, tears make them wet again.

Variable passions throng her constant woe,

As striving who should best become her grief.

All entertained, each passion labours so

That every present sorrow seemeth chief,

But none is best. Then join they all together,

Like many clouds consulting for foul weather.

By this, far off she hears some huntsman hollo;

A nurse’s song ne’er pleased her babe so well.

The dire imagination she did follow

This sound of hope doth labour to expel;

For now reviving joy bids her rejoice

And flatters her it is Adonis’ voice.

Whereat her tears began to turn their tide,

Being prisoned in her eye like pearls in glass;

Yet sometimes falls an orient drop beside,

Which her cheek melts, as scorning it should pass

To wash the foul face of the sluttish ground,

Who is but drunken when she seemeth drowned.

O hard-believing love—how strange it seems

Not to believe, and yet too credulous!

Thy weal and woe are both of them extremes.

Despair, and hope, makes thee ridiculous.

The one doth flatter thee in thoughts unlikely;

In likely thoughts the other kills thee quickly.

Now she unweaves the web that she hath wrought.

Adonis lives, and death is not to blame.

It was not she that called him all to naught.

Now she adds honours to his hateful name.

She clepes him king of graves, and grave for kings,

Imperious supreme of all mortal things.

‘No, no,’ quoth she, ‘sweet death, I did but jest.

Yet pardon me, I felt a kind of fear

Whenas I met the boar, that bloody beast,

Which knows no pity, but is still severe.

Then, gentle shadow—truth I must confess—

I railed on thee, fearing my love’s decease.

“Tis not my fault; the boar provoked my tongue.

Be wreaked on him, invisible commander.

’Tis he, foul creature, that hath done thee wrong.

I did but act; he’s author of thy slander.

Grief hath two tongues, and never woman yet

Could rule them both, without ten women’s wit.’

Thus, hoping that Adonis is alive,

Her rash suspect she doth extenuate,

And, that his beauty may the better thrive,

With death she humbly doth insinuate;

Tells him of trophies, statues, tombs; and stories

His victories, his triumphs, and his glories.

‘O Jove,’ quoth she, ‘how much a fool was I

To be of such a weak and silly mind

To wail his death who lives, and must not die

Till mutual overthrow of mortal kind!

For he being dead, with him is beauty slain,

And beauty dead, black chaos comes again.

‘Fie, fie, fond love, thou art as full of fear

As one with treasure laden, hemmed with thieves.

Trifles unwitnessèd with eye or ear

Thy coward heart with false bethinking grieves.’

Even at this word she hears a merry horn,

Whereat she leaps, that was but late forlorn.

As falcons to the lure, away she flies.

The grass stoops not, she treads on it so light;

And in her haste unfortunately spies

The foul boar’s conquest on her fair delight;

Which seen, her eyes, as murdered with the view,

Like stars ashamed of day, themselves withdrew.

Or as the snail, whose tender horns being hit

Shrinks backward in his shelly cave with pain,

And there, all smothered up, in shade doth sit,

Long after fearing to creep forth again;

So at his bloody view her eyes are fled

Into the deep dark cabins of her head,

Where they resign their office and their light

To the disposing of her troubled brain,

Who bids them still consort with ugly night,

And never wound the heart with looks again,

Who, like a king perplexed in his throne,

By their suggestion gives a deadly groan,

Whereat each tributary subject quakes,

As when the wind, imprisoned in the ground,

Struggling for passage, earth’s foundation shakes,

Which with cold terror doth men’s minds confound.

This mutiny each part doth so surprise

That from their dark beds once more leap her eyes,

And, being opened, threw unwilling light

Upon the wide wound that the boar had trenched

In his soft flank, whose wonted lily-white

With purple tears that his wound wept was drenched.

No flower was nigh, no grass, herb, leaf, or weed,

But stole his blood, and seemed with him to bleed.

This solemn sympathy poor Venus noteth.

Over one shoulder doth she hang her head.

Dumbly she passions, franticly she doteth.

She thinks he could not die, he is not dead.

Her voice is stopped, her joints forget to bow,

Her eyes are mad that they have wept till now.

Upon his hurt she looks so steadfastly

That her sight, dazzling, makes the wound seem three;

And then she reprehends her mangling eye,

That makes more gashes where no breach should be.

His face seems twain; each several limb is doubled;

For oft the eye mistakes, the brain being troubled.

‘My tongue cannot express my grief for one,

And yet,’ quoth she, ‘behold two Adons dead!

My sighs are blown away, my salt tears gone,

Mine eyes are turned to fire, my heart to lead.

Heavy heart’s lead, melt at mine eyes’ red fire!

So shall I die by drops of hot desire.

‘Alas, poor world, what treasure hast thou lost,

What face remains alive that’s worth the viewing?

Whose tongue is music now? What canst thou boast

Of things long since, or anything ensuing?

The flowers are sweet, their colours fresh and trim;

But true sweet beauty lived and died with him.

‘Bonnet nor veil henceforth no creature wear:

Nor sun nor wind will ever strive to kiss you.

Having no fair to lose, you need not fear.

The sun doth scorn you, and the wind doth hiss you.

But when Adonis lived, sun and sharp air

Lurked like two thieves to rob him of his fair;

‘And therefore would he put his bonnet on,

Under whose brim the gaudy sun would peep.

The wind would blow it off, and, being gone,

Play with his locks; then would Adonis weep,

And straight, in pity of his tender years,

They both would strive who first should dry his tears.

‘To see his face the lion walked along

Behind some hedge, because he would not fear him.

To recreate himself when he hath sung,

The tiger would be tame, and gently hear him.

If he had spoke, the wolf would leave his prey,

And never fright the silly lamb that day.

‘When he beheld his shadow in the brook,

The fishes spread on it their golden gills.

When he was by, the birds such pleasure took

That some would sing, some other in their bills

Would bring him mulberries and ripe-red cherries.

He fed them with his sight, they him with berries.

‘But this foul, grim, and urchin-snouted boar,

Whose downward eye still looketh for a grave,

Ne’er saw the beauteous livery that he wore:

Witness the entertainment that he gave:

If he did see his face, why then, I know

He thought to kiss him, and hath killed him so.

“Tis true, ’tis true; thus was Adonis slain;

He ran upon the boar with his sharp spear,

Who did not whet his teeth at him again,

But by a kiss thought to persuade him there,

And, nuzzling in his flank, the loving swine

Sheathed unaware the tusk in his soft groin.

‘Had I been toothed like him, I must confess

With kissing him I should have killed him first;

But he is dead, and never did he bless

My youth with his, the more am I accursed.’

With this she falleth in the place she stood,

And stains her face with his congealed blood.

She looks upon his lips, and they are pale.

She takes him by the hand, and that is cold.

She whispers in his ears a heavy tale,

As if they heard the woeful words she told.

She lifts the coffer-lids that close his eyes,

Where lo, two lamps burnt out in darkness lies;

Two glasses, where herself herself beheld

A thousand times, and now no more reflect,

Their virtue lost, wherein they late excelled,

And every beauty robbed of his effect.

‘Wonder of time,’ quoth she, ‘this is my spite,

That, thou being dead, the day should yet be light.

‘Since thou art dead, lo, here I prophesy

Sorrow on love hereafter shall attend.

It shall be waited on with jealousy,

Find sweet beginning, but unsavoury end;

Ne’er settled equally, but high or low,

That all love’s pleasure shall not match his woe.

‘It shall be fickle, false, and full of fraud,

Bud, and be blasted, in a breathing-while:

The bottom poison, and the top o’erstrawed

With sweets that shall the truest sight beguile.

The strongest body shall it make most weak,

Strike the wise dumb, and teach the fool to speak.

‘It shall be sparing, and too full of riot,

Teaching decrepit age to tread the measures.

The staring ruffian shall it keep in quiet,

Pluck down the rich, enrich the poor with treasures;

It shall be raging-mad, and silly-mild;

Make the young old, the old become a child.

‘It shall suspect where is no cause of fear;

It shall not fear where it should most mistrust.

It shall be merciful, and too severe,

And most deceiving when it seems most just.

Perverse it shall be where it shows most toward,

Put fear to valour, courage to the coward.

‘It shall be cause of war and dire events,

And set dissension ’twixt the son and sire;

Subject and servile to all discontents,

As dry combustious matter is to fire.

Sith in his prime death doth my love destroy,

They that love best their loves shall not enjoy.’

By this, the boy that by her side lay killed

Was melted like a vapour from her sight,

And in his blood that on the ground lay spilled

A purple flower sprung up, chequered with white,

Resembling well his pale cheeks, and the blood

Which in round drops upon their whiteness stood.

She bows her head the new-sprung flower to smell,

Comparing it to her Adonis’ breath,

And says within her bosom it shall dwell,

Since he himself is reft from her by death.

She crops the stalk, and in the breach appears

Green-dropping sap, which she compares to tears.

‘Poor flower,’ quoth she, ‘this was thy father’s guise—

Sweet issue of a more sweet-smelling sire—

For every little grief to wet his eyes.

To grow unto himself was his desire,

And so ’tis thine; but know it is as good

To wither in my breast as in his blood.

‘Here was thy father’s bed, here in my breast.

Thou art the next of blood, and ’tis thy right.

Lo, in this hollow cradle take thy rest;

My throbbing heart shall rock thee day and night.

There shall not be one minute in an hour

Wherein I will not kiss my sweet love’s flower.’

Thus, weary of the world, away she hies,

And yokes her silver doves, by whose swift aid

Their mistress, mounted, through the empty skies

In her light chariot quickly is conveyed,

Holding their course to Paphos, where their queen

Means to immure herself, and not be seen.

THE RAPE OF LUCRECE

DEDICATING Venus and Adonis to the Earl of Southampton in I953, Shakespeare promised, if the poem pleased, to ‘take advantage of all idle hours’ to honour the Earl with ‘some graver labour’. The Rape of Lucrece, also dedicated to Southampton, was entered in the Stationers’ Register on May I594, and printed in the same year. The warmth of the dedication suggests that the Earl was by then a friend as well as a patron.

Like Venus and Adonis, The Rape of Lucrece is an erotic narrative based on Ovid, but this time the subject matter is historical, the tone tragic. The events took place in 509 BC, and were already legendary at the time of the first surviving account, by Livy in his history of Rome published between 27 and 27 5 BC. Shakespeare’s main source was Ovid’s Fasti, but he seems also to have known Livy’s and other accounts.

Historically, Lucretia’s rape had political consequences. Her ravisher, Tarquin, was a member of the tyrannical ruling family of Rome. During the siege of Ardea, a group of noblemen boasted of their wives’ virtue, and rode home to test them; only Collatine’s wife, Lucretia, lived up to her husband’s claims, and Sextus Tarquinius was attracted to her. Failing to seduce her, he raped her and returned to Rome. Lucretia committed suicide, and her husband’s friend, Lucius Junius Brutus, used the occasion as an opportunity to rouse the Roman people against Tarquinius’ rule and to constitute themselves a republic.

Shakespeare concentrates on the private side of the story; Tarquin is lusting after Lucrece in the poem’s opening lines, and the ending devotes only a few lines to the consequence of her suicide. As in Venus and Adonis, Shakespeare makes a little narrative material go a long way. At first, the focus is on Tarquin; after he has threatened Lucrece, it swings over to her. The opening sequence, with its marvellously dramatic account of Tarquin’s tormented state of mind as he approaches Lucrece’s chamber, is the more intense. Tarquin disappears from the action soon after the rape, when Lucrece delivers herself of a long complaint, apostrophizing night, opportunity, and time and cursing Tarquin with rhetorical fervour, before deciding to kill herself. After summoning her husband, she seeks consolation in a painting of Troy which is described (I373-I442) in lines indebted to the first and second books of Virgil’s Aeneid and to Book I3 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. After she dies, her husband and father mourn, but Brutus calls for deeds not words, and determines on revenge. The last lines of the poem look forward to the banishment of the Tarquins, but nothing is said of the establishment of a republic.

Like Venus and Adonis, Lucrece, initially popular (with six editions in Shakespeare’s lifetime and another three by I655), was later neglected. Coleridge admired it, and more recent criticism has recognized in it a profoundly dramatic quality combined with, if sometimes dissipated by, a remarkable force of rhetoric. The writing of the poem seems to have been a formative experience for Shakespeare. In it he not only laid the basis for his later plays on Roman history, but also explored themes that were to figure prominently in his later work. This is especially apparent in the portrayal of a man who ‘still pursues his fear’ (308), the relentless power of self-destructive evil that Shakespeare remembered when he made Macbeth, on his way to murder Duncan, speak of ‘withered murder’ which, ‘With Tarquin’s ravishing strides, towards his design ǀ Moves like a ghost’.

TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENRY WRIOTHESLEY, EARL OF SOUTHAMPTON AND BARON OF TITCHFIELD

The love I dedicate to your lordship is without end, whereof this pamphlet without beginning is but a superfluous moiety. The warrant I have of your honourable disposition, not the worth of my untutored lines, makes it assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours. Were my worth greater my duty would show greater, meantime, as it is, it is bound to your lordship, to whom I wish long life still lengthened with all happiness.

Your lordship’s in all duty,

William Shakespeare

THE ARGUMENT

Lucius Tarquinius (for his excessive pride surnamed Superbus), after he had caused his own father-in-law Servius Tullius to be cruelly murdered, and, contrary to the Roman laws and customs, not requiring or staying for the people’s suffrages had possessed himself of the kingdom, went accompanied with his sons and other noblemen of Rome to besiege Ardea, during which siege the principal men of the army meeting one evening at the tent of Sextus Tarquinius, the King’s son, in their discourses after supper everyone commended the virtues of his own wife, among whom Collatinus extolled the incomparable chastity of his wife, Lucretia. In that pleasant humour they all posted to Rome, and, intending by their secret and sudden arrival to make trial of that which everyone had before avouched, only Collatinus finds his wife (though it were late in the night) spinning amongst her maids. The other ladies were all found dancing, and revelling, or in several disports. Whereupon the noblemen yielded Collatinus the victory and his wife the fame. At that time Sextus Tarquinius, being enflamed with Lucrece’ beauty, yet smothering his passions for the present, departed with the rest back to the camp, from whence he shortly after privily withdrew himself and was, according to his estate, royally entertained and lodged by Lucrece at Collatium. The same night he treacherously stealeth into her chamber, violently ravished her, and early in the morning speedeth away. Lucrece, in this lamentable plight, hastily dispatcheth messengers—one to Rome for her father, another to the camp for Collatine. They came, the one accompanied with Junius Brutus, the other with Publius Valerius, and, finding Lucrece attired in mourning habit, demanded the cause of her sorrow. She, first taking an oath of them for her revenge, revealed the actor and whole manner of his dealing, and withal suddenly stabbed herself. Which done, with one consent they all vowed to root out the whole hated family of the Tarquins, and, bearing the dead body to Rome, Brutus acquainted the people with the doer and manner of the vile deed, with a bitter invective against the tyranny of the King; wherewith the people were so moved that with one consent and a general acclamation the Tarquins were all exiled and the state government changed from kings to consuls.

The Rape of Lucrece

From the besieged Ardea all in post,

Borne by the trustless wings of false desire,

Lust-breathèd Tarquin leaves the Roman host

And to Collatium bears the lightless fire

Which, in pale embers hid, lurks to aspire

And girdle with embracing flames the waist

Of Collatine’s fair love, Lucrece the chaste.

Haply that name of chaste unhapp’ly set

This bateless edge on his keen appetite,

When Collatine unwisely did not let

To praise the clear unmatched red and white

Which triumphed in that sky of his delight,

Where mortal stars as bright as heaven’s beauties

With pure aspects did him peculiar duties.

For he the night before in Tarquin’s tent

Unlocked the treasure of his happy state,

What priceless wealth the heavens had him lent

In the possession of his beauteous mate,

Reck’ning his fortune at such high-proud rate

That kings might be espoused to more fame,

But king nor peer to such a peerless dame.

O happiness enjoyed but of a few,

And, if possessed, as soon decayed and done

As is the morning’s silver melting dew

Against the golden splendour of the sun,

An expired date cancelled ere well begun!

Honour and beauty in the owner’s arms

Are weakly fortressed from a world of harms.

Beauty itself doth of itself persuade

The eyes of men without an orator.

What needeth then apology be made

To set forth that which is so singular?

Or why is Collatine the publisher

Of that rich jewel he should keep unknown

From thievish ears, because it is his own?

Perchance his boast of Lucrece’ sov’reignty

Suggested this proud issue of a king,

For by our ears our hearts oft tainted be.

Perchance that envy of so rich a thing,

Braving compare, disdainfully did sting

His high-pitched thoughts, that meaner men should vaunt

That golden hap which their superiors want.

But some untimely thought did instigate

His all-too-timeless speed, if none of those.

His honour, his affairs, his friends, his state

Neglected all, with swift intent he goes

To quench the coal which in his liver glows.

O rash false heat, wrapped in repentant cold,

Thy hasty spring still blasts and ne’er grows old!

When at Collatium this false lord arrived,

Well was he welcomed by the Roman dame,

Within whose face beauty and virtue strived

Which of them both should underprop her fame.

When virtue bragged, beauty would blush for shame;

When beauty boasted blushes, in despite

Virtue would stain that or with silver white.

But beauty, in that white entitulèd

From Venus’ doves, doth challenge that fair field.

Then virtue claims from beauty beauty’s red,

Which virtue gave the golden age to gild

Their silver cheeks, and called it then their shield,

Teaching them thus to use it in the fight:

When shame assailed, the red should fence the

white.

This heraldry in Lucrece’ face was seen,

Argued by beauty’s red and virtue’s white.

Of either’s colour was the other queen,

Proving from world’s minority their right.

Yet their ambition makes them still to fight,

The sovereignty of either being so great

That oft they interchange each other’s seat.

This silent war of lilies and of roses

Which Tarquin viewed in her fair face’s field

In their pure ranks his traitor eye encloses,

Where, lest between them both it should be killed,

The coward captive vanquished doth yield

To those two armies that would let him go

Rather than triumph in so false a foe.

Now thinks he that her husband’s shallow tongue,

The niggard prodigal that praised her so,

In that high task hath done her beauty wrong,

Which far exceeds his barren skill to show.

Therefore that praise which Collatine doth owe

Enchanted Tarquin answers with surmise

In silent wonder of still-gazing eyes.

This earthly saint adored by this devil

Little suspecteth the false worshipper,

For unstained thoughts do seldom dream on evil.

Birds never limed no secret bushes fear,

So guiltless she securely gives good cheer

And reverent welcome to her princely guest,

Whose inward ill no outward harm expressed,

For that he coloured with his high estate,

Hiding base sin in pleats of majesty,

That nothing in him seemed inordinate

Save sometime too much wonder of his eye,

Which, having all, all could not satisfy,

But poorly rich so wanteth in his store

That, cloyed with much, he pineth still for more.

But she that never coped with stranger eyes

Could pick no meaning from their parling looks,

Nor read the subtle shining secrecies

Writ in the glassy margins of such books.

She touched no unknown baits nor feared no hooks,

Nor could she moralize his wanton sight

More than his eyes were opened to the light.

He stories to her ears her husband’s fame

Won in the fields of fruitful Italy,

And decks with praises Collatine’s high name

Made glorious by his manly chivalry

With bruised arms and wreaths of victory.

Her joy with heaved-up hand she doth express,

And wordless so greets heaven for his success.

Far from the purpose of his coming thither

He makes excuses for his being there.

No cloudy show of stormy blust’ring weather

Doth yet in his fair welkin once appear

Till sable night, mother of dread and fear,

Upon the world dim darkness doth display

And in her vaulty prison stows the day.

For then is Tarquin brought unto his bed,

Intending weariness with heavy sprite;

For after supper long he questioned

With modest Lucrece, and wore out the night.

Now leaden slumber with life’s strength doth fight,

And everyone to rest himself betakes

Save thieves, and cares, and troubled minds that

wakes.

As one of which doth Tarquin lie revolving

The sundry dangers of his will’s obtaining,

Yet ever to obtain his will resolving,

Though weak-built hopes persuade him to abstaining.

Despair to gain doth traffic oft for gaining,

And when great treasure is the meed proposed,

Though death be adjunct, there’s no death supposed.

Those that much covet are with gain so fond

That what they have not, that which they possess,

They scatter and unloose it from their bond,

And so by hoping more they have but less,

Or, gaining more, the profit of excess

Is but to surfeit and such griefs sustain

That they prove bankrupt in this poor-rich gain.

The aim of all is but to nurse the life

With honour, wealth, and ease in waning age,

And in this aim there is such thwarting strife

That one for all, or all for one, we gage,

As life for honour in fell battle’s rage,

Honour for wealth; and oft that wealth doth cost

The death of all, and all together lost.

So that, in vent’ring ill, we leave to be

The things we are for that which we expect,

And this ambitious foul infirmity

In having much, torments us with defect

Of that we have; so then we do neglect

The thing we have, and all for want of wit

Make something nothing by augmenting it.

Such hazard now must doting Tarquin make,

Pawning his honour to obtain his lust,

And for himself himself he must forsake.

Then where is truth if there be no self-trust?

When shall he think to find a stranger just

When he himself himself confounds, betrays

To sland’rous tongues and wretched hateful days?

Now stole upon the time the dead of night

When heavy sleep had closed up mortal eyes.

No comfortable star did lend his light,

No noise but owls’ and wolves’ death-boding cries

Now serves the season, that they may surprise

The silly lambs. Pure thoughts are dead and still,

While lust and murder wakes to stain and kill.

And now this lustful lord leapt from his bed,

Throwing his mantle rudely o‘er his arm,

Is madly tossed between desire and dread.

Th’one sweetly flatters, th’other feareth harm,

But honest fear, bewitched with lust’s foul charm,

Doth too-too oft betake him to retire,

Beaten away by brainsick rude desire.

His falchion on a flint he softly smiteth,

That from the cold stone sparks of fire do fly,

Whereat a waxen torch forthwith he lighteth,

Which must be lodestar to his lustful eye,

And to the flame thus speaks advisedly:

‘As from this cold flint I enforced this fire,

So Lucrece must I force to my desire.’

Here pale with fear he doth premeditate

The dangers of his loathsome enterprise,

And in his inward mind he doth debate

What following sorrow may on this arise.

Then, looking scornfully, he doth despise

His naked armour of still-slaughtered lust,

And justly thus controls his thoughts unjust:

‘Fair torch, burn out thy light, and lend it not

To darken her whose light excelleth thine;

And die, unhallowed thoughts, before you blot

With your uncleanness that which is divine.

Offer pure incense to so pure a shrine.

Let fair humanity abhor the deed

That spots and stains love’s modest snow-white weed.

‘O shame to knighthood and to shining arms!

O foul dishonour to my household’s grave!

O impious act including all foul harms!

A martial man to be soft fancy’s slave!

True valour still a true respect should have;

Then my digression is so vile, so base,

That it will live engraven in my face.

‘Yea, though I die the scandal will survive

And be an eyesore in my golden coat.

Some loathsome dash the herald will contrive

To cipher me how fondly I did dote,

That my posterity, shamed with the note,

Shall curse my bones and hold it for no sin

To wish that I their father had not been.

‘What win I if I gain the thing I seek?

A dream, a breath, a froth of fleeting joy.

Who buys a minute’s mirth to wail a week,

Or sells eternity to get a toy?

For one sweet grape who will the vine destroy?

Or what fond beggar, but to touch the crown,

Would with the sceptre straight be strucken down?

‘If Collatinus dream of my intent

Will he not wake, and in a desp’rate rage

Post hither this vile purpose to prevent?—

This siege that hath engirt his marriage,

This blur to youth, this sorrow to the sage,

This dying virtue, this surviving shame,

Whose crime will bear an ever-during blame.

‘O what excuse can my invention make

When thou shalt charge me with so black a deed?

Will not my tongue be mute, my frail joints shake,

Mine eyes forgo their light, my false heart bleed?

The guilt being great, the fear doth still exceed,

And extreme fear can neither fight nor fly,

But coward-like with trembling terror die.

‘Had Collatinus killed my son or sire,

Or lain in ambush to betray my life,

Or were he not my dear friend, this desire

Might have excuse to work upon his wife

As in revenge or quittal of such strife.

But as he is my kinsman, my dear friend,

The shame and fault finds no excuse nor end.

‘Shameful it is—ay, if the fact be known.

Hateful it is—there is no hate in loving.

I’ll beg her love—but she is not her own.

The worst is but denial and reproving;

My will is strong past reason’s weak removing.

Who fears a sentence or an old man’s saw

Shall by a painted cloth be kept in awe.’

Thus graceless holds he disputation

‘Tween frozen conscience and hot-burning will,

And with good thoughts makes dispensation,

Urging the worser sense for vantage still;

Which in a moment doth confound and kill

All pure effects, and doth so far proceed

That what is vile shows like a virtuous. deed.

Quoth he, ‘She took me kindly by the hand,

And gazed for tidings in my eager eyes,

Fearing some hard news from the warlike band

Where her beloved Collatinus lies.

O how her fear did make her colour rise!

First red as roses that on lawn we lay,

Then white as lawn, the roses took away.

‘And how her hand, in my hand being locked,

Forced it to tremble with her loyal fear,

Which struck her sad, and then it faster rocked

Until her husband’s welfare she did hear,

Whereat she smiled with so sweet a cheer

That had Narcissus seen her as she stood

Self-love had never drowned him in the flood.

‘Why hunt I then for colour or excuses?

All orators are dumb when beauty pleadeth.

Poor wretches have remorse in poor abuses;

Love thrives not in the heart that shadows dreadeth;

Affection is my captain, and he leadeth,

And when his gaudy banner is displayed,

The coward fights, and will not be dismayed.

‘Then childish fear avaunt, debating die,

Respect and reason wait on wrinkled age!

My heart shall never countermand mine eye,

Sad pause and deep regard beseems the sage.

My part is youth, and beats these from the stage.