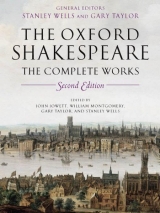

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 196 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

PERICLES

BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND GEORGE WILKINS A RECONSTRUCTED TEXT

ON 20 May 1608 Pericles was entered on the Stationers’ Register to Edward Blount; but he did not publish it. Probably the players allowed him to license it in the hope of preventing its publication by anyone else, for it was one of the most popular plays of the period. Its success was exploited, also in 1608, by the publication of a novel, by George Wilkins, ‘The Painful Adventures of Pericles Prince of Tyre, Being the True History of the Play of Pericles, as it was lately presented by the worthy and ancient poet John Gower’. The play itself appeared in print in the following year, with an ascription to Shakespeare, but in a manifestly corrupt text that gives every sign of having been put together from memory. This quarto was several times reprinted, but the play was not included in the 1623 Folio (perhaps because Heminges and Condell knew that Shakespeare was responsible for only part of it).

In putting together The Painful Adventures, Wilkins drew on an earlier version of the tale, The Pattern of Painful Adventures, by Laurence Twine, written in the mid-1570s and reprinted in 1607. Twine’s book is also a source of the play, which draws too on the story of Apollonius of Tyre as told by John Gower in his Confessio Amantis, and, to a lesser extent, on Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia. Wilkins not only incorporated verbatim passages from Twine’s book, he also drew heavily on Pericles itself. Since the play text is so corrupt, it is quite likely that Wilkins reports parts of it both more accurately and more fully than the quarto. And he may have had special qualifications for doing so. He was a dramatist whose popular play The Miseries of Enforced Marriage had been performed by Shakespeare’s company. Pericles has usually been regarded as either a collaborative play or one in which Shakespeare revised a pre-existing script. Our edition is based on the hypothesis (not new) that Wilkins was its joint author. Our attempt to reconstruct the play draws more heavily than is usual on Wilkins’s novel, especially in the first nine scenes (which he probably wrote); in general, because of its obvious corruption, the original text is more freely emended than usual. So that readers may experience the play as originally printed, an unemended reprint of the 1609 quarto is given in our original-spelling edition. The deficiencies of the text are in part compensated for by the survival of an unusual amount of relevant visual material, reproduced overleaf.

The complex textual background of Pericles should not be allowed to draw attention away from the merits of this dramatic romance, which we hope will be more apparent as the result of our treatment of the text. If the original play had survived, it might well have been as highly valued as The Winter’s Tale or The Tempest; as it is, it contains some hauntingly beautiful episodes, above all that in Scene 21 in which Marina, Pericles’ long-lost daughter, draws him out of the comatose state to which his sufferings have reduced him.

14. From the title-page of The Painful Adventures of Pericles Prince of Tyre (1608), by George Wilkins; artist unknown. Since Gower is not a character in Wilkins’s novel, the choice of woodcut undoubtedly reflects both the play’s popularity and Gower’s own impact in early performances, and it is as likely to reflect the visual detail of performance as any early title-page. The sprig of laurel (or posy) in Gower’s left hand is symbolic of his poetic status.

15. From Greene’s Vision (1592), sig. CIr―CIv; probably by Robert Greene. The description here fits reasonably well the Painful Adventures title-page, though the woodcut does not contain the ‘bag of red’, ‘napkin’, or tight-fitting ‘breech’.

16. Severed heads displayed on the gate of London Bridge, from an etching by Claes Jan Visscher (1616). In the play’s sources, and Painful Adventures, the heads of previous suitors (Sc. 1) are placed on the ’gate’ of Antioch. In performance they could have been thrust out on poles from the upper stage; but the timing and method of their display is not clear.

17.From The Heroical Devices of M. Claudius Paradin, translated by P.S. (1591), sig. V3. This is the source for the impresa of the Third Knight, in Sc. 6.

18. From The Heroical Devices of M. Claudius Paradin, translated by P.S. (1591), sig. Z3. This is the source for the impresa of the Fourth Knight, in Sc. 6.

19. An Inigo Jones sketch of Diana, probably for Ben Jonson’s masque Time Vindicated (1623). The goddess of chastity appeared as a character in court entertainments, masques, and plays, and her representation was governed by iconographic convention. As goddess of hunting, she was most often identified by her ‘silver bow’ (21.234). In Thomas Heywood’s The Golden Age (1611), stage directions refer to ‘Diana’s bow’ (sig. EIv) and her ‘buskins’ (sig. E3v); her ‘nymphs’ explicitly, and by inference she, have ‘garlands on their heads, and javelins in their hands ... bows and quivers’ (sig. D3v). The bow, quiver, and javelin, all visible in Jones’s sketch, were commonplace in emblematic representations. As a huntress, Diana could naturally be envisaged in a chariot: in Aurelian Townshend’s masque Albion’s Triumph (1631), she descends ‘in her chariot’ (pp. 2, 12); in Time Vindicated, ‘Diana descends’ (1. 446). Such descents for deities were used in the public theatres, too, usually in a chair or chariot (21.224.2).

20. A miniature of Diana by Isaac Oliver (1615): the dress is yellow, the scarf a gauzy pink-white, the cloak over her right shoulder blue; the leaf-shaped brooch topped by the crescent moon, gold. In Samuel Daniel’s masque The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses (1604), ‘Diana, in a green mantle embroidered with silver half moons, and a crescent of pearl on her head, presents a bow and quiver’ (sig. A5). The ‘crescent of pearl’—an ornamental crescent moon, also detectable in Jones’s sketch—can be seen in many emblematic representations of the goddess.

21. For the pastoral Florimène (1635), Inigo Jones designed two scenic views of ’The Temple of Diana’ (see 1. 22.17.1). Though such scenes were not used in the public theatres in Shakespeare’s time, the columns supporting the overhanging roof of the public stage (see General Introduction, pp. xxvii-xxix) could have created a scenic effect roughly similar to Jones’s recessed classical temple. Statues were also available as props in the public theatre; in Pericles, as in The Winter’s Tale, the statue could have been impersonated by an actor on a pedestal. Whether or not a statue was visible, the temple could be identified by an altar (as in The Two Noble Kinsmen).

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

John GOWER, the Presenter

ANTIOCHUS, King of Antioch

His DAUGHTER

THALIART, a villain

PERICLES, Prince of Tyre

MARINA, Pericles’ daughter

CLEON, Governor of Tarsus

DIONIZA, his wife

LEONINE, a murderer

KING SIMONIDES, of Pentapolis

THAISA, his daughter

Three FISHERMEN, his subjects

Five PRINCES, suitors of Thaisa

A MARSHAL

LYCHORIDA, Thaisa’s nurse

CERIMON, a physician of Ephesus

PHILEMON, his servant

LYSIMACHUS, Governor of Mytilene

A BAWD

A PANDER

BOULT, a leno

DIANA, goddess of chastity

Lords, ladies, pages, messengers, sailors, gentlemen

A Reconstructed Text of Pericles, Prince of Tyre

Sc. 1 Enter Gower as Prologue

GOWER

To sing a song that old was sung

From ashes ancient Gower is come,

Assuming man’s infirmities

To glad your ear and please your eyes.

It hath been sung at festivals,

On ember-eves and holy-ales,

And lords and ladies in their lives

Have read it for restoratives.

The purchase is to make men glorious,

Et bonum quo antiquius eo melius.

If you, born in these latter times

When wit’s more ripe, accept my rhymes,

And that to hear an old man sing

May to your wishes pleasure bring,

I life would wish, and that I might

Waste it for you like taper-light.

This’ Antioch, then; Antiochus the Great

Built up this city for his chiefest seat,

The fairest in all Syria.

I tell you what mine authors say.

This king unto him took a fere

Who died, and left a female heir

So buxom, blithe, and full of face

As heav’n had lent her all his grace,

With whom the father liking took,

And her to incest did provoke.

Bad child, worse father, to entice his own

To evil should be done by none.

By custom what they did begin

Was with long use account’ no sin.

The beauty of this sinful dame

Made many princes thither frame

To seek her as a bedfellow,

In marriage pleasures playfellow,

Which to prevent he made a law

To keep her still, and men in awe,

That whoso asked her for his wife,

His riddle told not, lost his life.

So for her many a wight did die,

⌈A row of heads is revealed⌉

As yon grim looks do testify.

What now ensues, to th’ judgement of your eye

I give, my cause who best can justify. Exit

⌈Sennet.⌉ Enter King Antiochus, Prince Pericles, and ⌈lords and peers in their richest ornaments⌉

ANTIOCHUS

Young Prince of Tyre, you have at large received

The danger of the task you undertake.

PERICLES

I have, Antiochus, and with a soul

Emboldened with the glory of her praise

Think death no hazard in this enterprise.

ANTIOCHUS Music!

Music sounds

Bring in our daughter, clothèd like a bride

Fit for th’embracements ev’n of Jove himself,

At whose conception, till Lucina reigned,

Nature this dowry gave to glad her presence:

The senate-house of planets all did sit,

In her their best perfections to knit.

Enter Antiochus’ Daughter

PERICLES

See where she comes, apparelled like the spring,

Graces her subjects, and her thoughts the king

Of ev’ry virtue gives renown to men;

Her face the book of praises, where is read

Nothing but curious pleasures, as from thence

Sorrow were ever razed and testy wrath

Could never be her mild companion.

You gods that made me man, and sway in love,

That have inflamed desire in my breast

To taste the fruit of yon celestial tree

Or die in the adventure, be my helps,

As I am son and servant to your will,

To compass such a boundless happiness.

ANTIOCHUS Prince Pericles—

PERICLES

That would be son to great Antiochus.

ANTIOCHUS

Before thee stands this fair Hesperides,

With golden fruit, but dang’rous to be touched,

⌈He gestures towards the heads⌉

For death-like dragons here affright thee hard.

⌈He gestures towards his daughter⌉

Her heav‘n-like face enticeth thee to view

Her countless glory, which desert must gain;

And which without desert, because thine eye

Presumes to reach, all the whole heap must die.

Yon sometimes famous princes, like thyself

Drawn by report, advent’rous by desire,

Tell thee with speechless tongues and semblants

bloodless

That without covering save yon field of stars

Here they stand, martyrs slain in Cupid’s wars,

And with dead cheeks advise thee to desist

From going on death’s net, whom none resist.

PERICLES

Antiochus, I thank thee, who hath taught

My frail mortality to know itself,

And by those fearful objects to prepare

This body, like to them, to what I must;

For death remembered should be like a mirror

Who tells us life’s but breath, to trust it error.

I’ll make my will then, and, as sick men do,

Who know the world, see heav‘n, but feeling woe

Grip not at earthly joys as erst they did,

So I bequeath a happy peace to you

And all good men, as ev’ry prince should do;

My riches to the earth from whence they came,

(To the Daughter) But my unspotted fire of love to you.

(To Antiochus) Thus ready for the way of life or death,

I wait the sharpest blow, Antiochus.

ANTIOCHUS

Scorning advice, read the conclusion then,

⌈He angrily throws down the riddle⌉

Which read and not expounded, ’tis decreed,

As these before thee, thou thyself shalt bleed.

DAUGHTER (to Pericles)

Of all ‘sayed yet, mayst thou prove prosperous;

Of all ’sayed yet, I wish thee happiness.

PERICLES

Like a bold champion I assume the lists,

Nor ask advice of any other thought

But faithfulness and courage.

⌈He takes up and⌉ reads aloud the riddle

I am no viper, yet I feed

On mother’s flesh which did me breed.

I sought a husband, in which labour

I found that kindness in a father.

He’s father, son, and husband mild;

I mother, wife, and yet his child.

How this may be and yet in two,

As you will live resolve it you.

Sharp physic is the last. ⌈Aside⌉ But O, you powers

That gives heav’n countless eyes to view men’s acts,

Why cloud they not their sights perpetually

If this be true which makes me pale to read it?

⌈He gazes on the Daughter⌉

Fair glass of light, I loved you, and could still,

Were not this glorious casket stored with ill.

But I must tell you now my thoughts revolt,

For he’s no man on whom perfections wait

That, knowing sin within, will touch the gate.

You’re a fair viol, and your sense the strings

Who, fingered to make man his lawful music,

Would draw heav’n down and all the gods to hearken,

But, being played upon before your time,

Hell only danceth at so harsh a chime.

Good sooth, I care not for you.

ANTIOCHUS

Prince Pericles, touch not, upon thy life,

For that’s an article within our law

As dang’rous as the rest. Your time’s expired.

Either expound now, or receive your sentence.

PERICLES Great King,

Few love to hear the sins they love to act.

‘Twould braid yourself too near for me to tell it.

Who has a book of all that monarchs do,

He’s more secure to keep it shut than shown,

For vice repeated, like the wand’ring wind,

Blows dust in others’ eyes to spread itself;

And yet the end of all is bought thus dear,

The breath is gone, and the sore eyes see clear

To stop the air would hurt them. The blind mole casts

Copped hills towards heav’n to tell the earth is thronged

By man’s oppression, and the poor worm doth die for’t.

Kings are earth’s gods; in vice their law’s their will,

And if Jove stray, who dares say Jove doth ill?

It is enough you know, and it is fit,

What being more known grows worse, to smother it.

All love the womb that their first being bred;

Then give my tongue like leave to love my head.

ANTIOCHUS (aside)

Heav’n, that I had thy head! He’s found the meaning.

But I will gloze with him.—Young Prince of Tyre,

Though by the tenor of our strict edict,

Your exposition misinterpreting,

We might proceed to cancel of your days,

Yet hope, succeeding from so fair a tree

As your fair self, doth tune us otherwise.

Forty days longer we do respite you,

If by which time our secret be undone,

This mercy shows we’ll joy in such a son.

And until then your entertain shall be

As doth befit your worth and our degree.

⌈Flourish.⌉Exeunt all but Pericles

PERICLES

How courtesy would seem to cover sin

When what is done is like an hypocrite,

The which is good in nothing but in sight.

If it be true that I interpret false,

Then were it certain you were not so bad

As with foul incest to abuse your soul,

Where now you’re both a father and a son

By your uncomely claspings with your child—

Which pleasures fits a husband, not a father—

And she, an eater of her mother’s flesh,

By the defiling of her parents’ bed,

And both like serpents are, who though they feed

On sweetest flowers, yet they poison breed.

Antioch, farewell, for wisdom sees those men

Blush not in actions blacker than the night

Will ’schew no course to keep them from the light.

One sin, I know, another doth provoke.

Murder’s as near to lust as flame to smoke.

Poison and treason are the hands of sin,

Ay, and the targets to put off the shame.

Then, lest my life be cropped to keep you clear,

By flight I’ll shun the danger which I fear. Exit

Enter Antiochus

ANTIOCHUS

He hath found the meaning, for the which we mean

To have his head. He must not live

To trumpet forth my infamy, nor tell the world

Antiochus doth sin in such a loathèd manner,

And therefore instantly this prince must die,

For by his fall my honour must keep high.

Who attends us there?

Enter Thaliart

THALIART

Doth your highness call?

ANTIOCHUS

Thaliart, you are of our chamber, Thaliart,

And to your secrecy our mind partakes

Her private actions. For your faithfulness

We will advance you, Thaliart. Behold,

Here’s poison, and here’s gold.

We hate the Prince of Tyre, and thou must kill him.

It fits thee not to ask the reason. Why?

Because we bid it. Say, is it done?

THALIART My lord, ’tis done.

ANTIOCHUS Enough.

Enter a Messenger hastily

Let your breath cool yourself, telling your haste.

MESSENGER

Your majesty, Prince Pericles is fled. ⌈Exit⌉

ANTIOCHUS (to Thaliart)

As thou wilt live, fly after; like an arrow

Shot from a well-experienced archer hits

The mark his eye doth level at, so thou

Never return unless it be to say

‘Your majesty, Prince Pericles is dead.’

THALIART

If I can get him in my pistol’s length

I’ll make him sure enough. Farewell, your highness.

ANTIOCHUS

Thaliart, adieu.

⌈Exit Thaliart⌉

Till Pericles be dead

My heart can lend no succour to my head.

Exit. ⌈The heads are concealed⌉

Sc. 2 Enter Pericles, distempered, with his lords

PERICLES

Let none disturb us.

Exeunt lords

Why should this change of thoughts,

The sad companion, dull-eyed melancholy,

Be my so used a guest as not an hour

In the day’s glorious walk or peaceful night,

The tomb where grief should sleep, can breed me

quiet? 5

Here pleasures court mine eyes, and mine eyes shun

them,

And danger, which I feared, ’s at Antioch,

Whose arm seems far too short to hit me here.

Yet neither pleasure’s art can joy my spirits,

Nor yet care’s author’s distance comfort me.

Then it is thus: the passions of the mind,

That have their first conception by misdread,

Have after-nourishment and life by care,

And what was first but fear what might be done

Grows elder now, and cares it be not done.

And so with me. The great Antiochus,

‘Gainst whom I am too little to contend,

Since he’s so great can make his will his act,

Will think me speaking though I swear to silence,

Nor boots it me to say I honour him

If he suspect I may dishonour him.

And what may make him blush in being known,

He’ll stop the course by which it might be known.

With hostile forces he’ll o’erspread the land,

And with th‘ostent of war will look so huge

Amazement shall drive courage from the state,

Our men be vanquished ere they do resist,

And subjects punished that ne’er thought offence,

Which care of them, not pity of myself,

Who am no more but as the tops of trees

Which fence the roots they grow by and defend them,

Makes both my body pine and soul to languish,

And punish that before that he would punish.

Enter all the Lords, among them old Helicanus, to Pericles

FIRST LORD

Joy and all comfort in your sacred breast!

SECOND LORD

And keep your mind peaceful and comfortable.

HELICANUS

Peace, peace, and give experience tongue.

(To Pericles) You do not well so to abuse yourself,

To waste your body here with pining sorrow,

Upon whose safety doth depend the lives

And the prosperity of a whole kingdom.

‘Tis ill in you to do it, and no less

ll in your council not to contradict it.

They do abuse the King that flatter him,

For flatt’ry is the bellows blows up sin;

The thing the which is flattered, but a spark,

To which that wind gives heat and stronger glowing;

Whereas reproof, obedient and in order,

Fits kings as they are men, for they may err.

When Signor Sooth here does proclaim a peace

He flatters you, makes war upon your life.

⌈He kneels⌉

Prince, pardon me, or strike me if you please.

I cannot be much lower than my knees.

PERICLES

All leave us else; but let your cares o’erlook

What shipping and what lading’s in our haven,

And then return to us. Exeunt Lords

Helicane, thou

Hast moved us. What seest thou in our looks?

HELICANUS An angry brow, dread lord.

PERICLES

If there be such a dart in princes’ frowns,

How durst thy tongue move anger to our brows?

HELICANUS

How dares the plants look up to heav’n from whence

They have their nourishment?

PERICLES

Thou knowest I have pow’r to take thy life from thee.

HELICANUS

I have ground the axe myself; do you but strike the blow.

PERICLES ⌈lifting him up⌉

Rise, prithee, rise. Sit down. Thou art no flatterer,

I thank thee for it, and the heav‘ns forbid

That kings should let their ears hear their faults hid.

Fit counsellor and servant for a prince,

Who by thy wisdom mak’st a prince thy servant,

What wouldst thou have me do?

HELICANUS

To bear with patience

Such griefs as you do lay upon yourself.

PERICLES

Thou speak‘st like a physician, Helicanus,

That ministers a potion unto me

That thou wouldst tremble to receive thyself.

Attend me, then. I went to Antioch,

Where, as thou know’st, against the face of death

I sought the purchase of a glorious beauty

From whence an issue I might propagate,

As children are heav‘n’s blessings: to parents,

objects;

Are arms to princes, and bring joys to subjects.

Her face was to mine eye beyond all wonder,

The rest—hark in thine ear—as black as incest,

Which by my knowledge found, the sinful father

Seemed not to strike, but smooth. But thou know’st

this,

‘Tis time to fear when tyrants seems to kiss;

Which fear so grew in me I hither fled

Under the covering of careful night,

Who seemed my good protector, and being here

Bethought me what was past, what might succeed.

I knew him tyrannous, and tyrants’ fears

Decrease not, but grow faster than the years.

And should he doubt—as doubt no doubt he doth—

That I should open to the list’ning air

How many worthy princes’ bloods were shed

To keep his bed of blackness unlaid ope,

To lop that doubt he’ll fill this land with arms,

And make pretence of wrong that I have done him,

When all for mine—if I may call—offence

Must feel war’s blow, who spares not innocence;

Which love to all, of which thyself art one,

Who now reproved’st me for’t—

HELICANUS

Alas, sir.

PERICLES

Drew sleep out of mine eyes, blood from my cheeks,

Musings into my mind, with thousand doubts,

How I might stop this tempest ere it came,

And, finding little comfort to relieve them,

I thought it princely charity to grieve them.

HELICANUS

Well, my lord, since you have giv’n me leave to speak,

Freely will I speak. Antiochus you fear,

And justly too, I think, you fear the tyrant,

Who either by public war or private treason

Will take away your life.

Therefore, my lord, go travel for a while,

Till that his rage and anger be forgot,

Or destinies do cut his thread of life.

Your rule direct to any; if to me,

Day serves not light more faithful than I’ll be.

PERICLES I do not doubt thy faith,

But should he in my absence wrong thy liberties?

HELICANUS

We’ll mingle our bloods together in the earth

From whence we had our being and our birth.

PERICLES

Tyre, I now look from thee then, and to Tarsus

Intend my travel, where I’ll hear from thee,

And by whose letters I’ll dispose myself.

The care I had and have of subjects’ good

On thee I lay, whose wisdom’s strength can bear it.

I’ll take thy word for faith, not ask thine oath;

Who shuns not to break one will sure crack both.

But in our orbs we’ll live so round and safe

That time of both this truth shall ne’er convince:

Thou showed’st a subject’s shine, I a true prince.

Exeunt