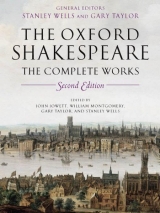

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

GRAMMAR IN DISCOURSE

Grammar is different from vocabulary in the way it appears in connected speech or writing. An individual word may not be present in a particular speech – or even in a whole scene – but core grammatical features are repeatedly used. Each page of this essay will provide many examples of the definite article, forms of the verb to be, plural endings, conjunctions such as and, and other essential features of sentence construction. In the same way, Shakespearian grammar repeatedly uses several Early Modern English features, such as older pronouns (thou, ye), inflectional endings (-est, -eth), and contracted forms (is’t, on’t). It is the frequency of use of such forms which can give a grammatical colouring to a speech – often, out of all proportion to their linguistic significance, as in this extract from Hamlet (5.1.271-5):

HAMLET (to Laertes) Swounds, show me what

thou’lt do.

Woot weep, woot fight, woot fast, woot tear thyself,

Woot drink up eisel, eat a crocodile?

I’ll do’t. Dost thou come here to whine,

To outface me with leaping in her grave?

Woot, often edited as woo’t, is a colloquial form of wilt or wouldst thou. It is a rare literary usage, but here its repetition, along with the other contracted forms and the use of thou, dominates the impression we have of the grammar, and gives an alien appearance to a speech which in all other respects is grammatically identical with Modern English:

Show me what you will do.

Will you weep, will you fight, will you fast, will you

tear yourself,

Will you drink up eisel, eat a crocodile?

I’ll do it. Do you come here to whine,

To outface me with leaping in her grave?

Several other distinctive features of Early Modern English grammar likewise present little difficulty to the modern reader. An example is the way in which a sequence of adjectives can appear both before and after the noun they modify, as in the Nurse’s description of Romeo (Romeo and Juliet, 2.4.55-6): ‘an honest gentleman, and a courteous, and a kind, and a handsome’ [= an honest, courteous, kind, and handsome gentleman]. Other transparent word-order variations include the reversal of adjective and possessive pronoun in good my lord, or the use of the double comparative in such phrases as more mightier and most poorest. Many individual words also have a different grammatical usage, compared with today, such as like (‘likely’) and something (‘somewhat’):

Very like, very like.

(Hamlet, 1.2.325)

I prattle | Something too wildly.

(Tempest, 3.1.57-8)

But here too the meaning is sufficiently close to modern idiom that they do not present a difficulty.

There are just a few types of construction where the usage is so far removed from anything we have in Modern English that, without special study, we are likely to miss the meaning of the sentence altogether. An example is the so-called ‘ethical dative’. Early Modern English allowed a personal pronoun after a verb to express such notions as ‘to’, ‘for’, ‘by’, ‘with’ or ‘from’ (notions which traditional grammars would subsume under the headings of the dative and ablative cases). The usage can be seen in such sentences as:

But hear me this (Twelfth Night, 5.1.118) [= But hear this from me]

John lays you plots (King John, 3.4.146) [= John lays plots for you to fall into]

It is an unfamiliar construction, to modern eyes and ears, and it can confuse – as a Shakespearian character himself evidences. In The Taming of the Shrew, Petruccio and Grumio arrive at Hortensio’s house (1.2.8-10):

PETRUCCIO Villain, I say, knock me here soundly.

GRUMIO Knock you here, sir? Why, sir, what am I, sir, that I should knock you here, sir?

Petruccio means ‘Knock on the door for me’, but Grumio interprets it to mean (as it would in Modern English) ‘hit me’. If we do not recognize the ethical dative in Petruccio’s sentence in the first place, we will miss the point of the joke entirely. But the fact that Grumio is confused suggests that the usage was probably already dying out in Shakespeare’s time.

GRAMMAR AND METRE

Most of the really unfamiliar deviations from Modern English grammatical norms which we encounter in Shakespeare arise in his verse, where he bends the construction to suit the demands of the metre. The approach to blank verse most favoured in Early Modern English took as its norm a line of five metrical units, or feet (a pentameter), with each foot in its most regular version represented by a two-syllable weak + strong (iambic) sequence, and the whole line ending in a natural pause and containing no internal break. Accordingly, the least amount of grammatical ‘bending’ takes place when a line coincides with the major unit of grammar, the sentence. This is a characteristic of much of Shakespeare’s early writing, as in this example from Queen Margaret:

Be woe for me, more wretched than he is.

What, dost thou turn away and hide thy face?

I am no loathsome leper – look on me!

What, art thou, like the adder, waxen deaf?

Be poisonous too and kill thy forlorn queen.

(The First Part of the Contention

(2 Henry VI), 3.2.73)

‘Sentence per line’ is the simplest kind of relationship between metre and grammar – and ‘clause per line’ is not very different. Such grammatically regular lines are often seen in the Sonnets, where they convey a measured rhythmical pace:

Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid

My verse alone had all thy gentle grace,

But now my gracious numbers are decayed,

And my sick muse doth give another place.

(Sonnet 79)

The pace of reading increases when the line-breaks coincide with a major point of grammatical junction within a clause, such as between a subject and verb, verb and object, or noun and relative clause. In this next example (Henry V, 4.3.64-5), because the first line contains only the clause subject, there is a dynamic tension at the end which propels us onwards to reach the verb:

And gentlemen in England now abed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here.

We can feel this tension if we stop our reading at the end of the first line. A subject alone is like an unresolved chord, calling out for the rest of the clause to provide semantic coherence.

Even when a sentence stretches over several lines, the relationship between metre and grammar can be regular, as we can see in this speech from the deposed king in Richard II (5.5.1-5):

I have been studying how I may compare

This prison where I live unto the world;

And for because the world is populous,

And here is not a creature but myself,

I cannot do it.

The line-endings are all major points of grammatical junction, so that each line makes a separate semantic point. By keeping the lines coherent, in this way, the meaning proceeds in a series of smooth, regular steps – very appropriate for a speech whose unique properties have been repeatedly praised: ‘No other speech in Shakespeare much resembles this one’ for its ‘quietly meditative’ tone (Frank Kermode, Shakespeare’s Language, p. 45). The effect would be totally lost if the lines did not coincide with these major units of grammar, as in this rewriting:

Today I have been studying how I may

Compare this prison where I live unto

The world . . .

Such lines no longer have a semantic coherence. Grammatical structures are begun but left unfinished: the auxiliary verb may is split off from its main verb compare; the preposition unto is split off from its noun phrase the world. That is not the metrical syntax of quiet meditation. On the other hand, it is precisely this sort of disruption which is needed when portraying a confused mind – in this case, Cloten’s (Cymbeline, 2.3.64-73):

I know her women are about her; what

If I do line one of their hands? ‘Tis gold

Which buys admittance—oft it doth—yea, and

makes

Diana’s rangers false themselves, yield up

Their deer to th’ stand o’th’ stealer; and ‘tis gold

Which makes the true man killed and saves the thief,

Nay, sometime hangs both thief and true man. What

Can it not do and undo? I will make

One of her women lawyer to me, for

I yet not understand the case myself.

Here several lines break in unexpected places (an effect partly captured by the traditional notion of caesura) – in the middle of a two-part conjunction (what |If), after an interrogative word (what), and between a conjunction and its clause (for | I) – and clauses begin at the end of lines instead of at the beginning. Cloten comments: ‘I yet not understand the case myself.’ The disruption between metre and grammar suggests as much.

The more the metre forces grammatical deviations within a line, the more difficult the line will be to understand. In this next example (Richard II, 1.1.123), three unexpected things happen at once: the direct object is placed at the front, the indirect object comes before the verb, and an adjective is coordinated after the noun. The glossed version is much clearer, but it is unmetrical: ‘Free speech and fearless I to thee allow’ [= I allow to thee free and fearless speech]. Sometimes the change in word order can catch us off-guard, as in this example from Contention (5.3.52-55), spoken by Young Clifford after seeing his dead father, and vowing revenge. Nothing, he says, will escape his wrath:

Tears virginal

Shall be to me even as the dew to fire,

And beauty that the tyrant oft reclaims

Shall to my flaming wrath be oil and flax.

A casual reading of the third line would suggest that ‘a tyrant often reclaims [i.e. tames, subdues] beauty’ – but this makes no sense. Rather, the meaning is ‘beauty, that often tames the tyrant, will act as fuel to my wrath’. Tyrant is not the grammatical subject of reclaims, but its object. Only by paying careful attention to the meaning can we work this out, and for this we need to think of the speech as a whole, and see it in its discourse context. Metre is often thought of simply as a phonetic phenomenon – an aesthetic sound effect, either heard directly or imagined when reading. In fact it is much more. Metrical choices always have grammatical, semantic, or pragmatic – as well as dramatic – consequences.

Line variations

Many special effects are achieved by departing from metrical norms – making lines longer or shorter than usual, juxtaposing different kinds of feet, or breaking lines in unexpected places. Short lines provide an important type of example. Whether these are introduced by an editorial or an authorial eye, there is always a semantic or pragmatic effect which needs to be carefully assessed. The short line, for example, is often used to mark a significant moment in a speech, especially a pointed contrast, as in this example from Othello (1.3.391-4):

The Moor is of a free and open nature,

That thinks men honest that but seem to be so,

And will as tenderly be led by th’ nose

As asses are.

Lines of five feet normally express three or four semantically specific points. In this example, the first two lines each contain four lexical items (Moor, free, open, nature; think, man, honest, seem), and the third has three (tenderly, lead, nose). By contrast, the semantic content of the fourth line is a single lexical item (ass), which now has to fill a semantic ‘space’ we normally associate with five feet. Several prosodic means are available to enable an actor to achieve this, such as slowing the tempo and rhythm of the syllables or varying the length of the final pause.

Splitlines – a five-foot line distributed over more than one speaker – must similarly be interpreted in semantic or pragmatic terms. From a semantic point of view, the space of the five-foot line is being filled with more content than is usual. From a prosodic point of view, the more switching between characters, the faster the pace. These factors operate most noticeably in the (rare) cases where a line is split into five interactive units, as in the scene in King John (3.3.64-6) when the King intimates to Hubert that Arthur should be killed:

From a pragmatic point of view, there is an immediate increase in the tempo of the interaction, which in turn conveys an increased sense of dramatic moment. On several occasions, the splitlines identify a critical point in the development of the plot, as in this example from The Winter’s Tale (1.2.412-13):

Sometimes, the switching raises the emotional temperature of the interaction. In this Hamlet example (4.5.126-7) we see the increased tempo conveying one person’s anger, immediately followed by another person’s anxiety:

An increase in tempo is also an ideal mechanism for carrying repartee. There are several examples in The Taming of the Shrew, when Petruccio and Katherine first meet, as here (2.1.234):

In a sequence like the following (The Tragedy of King Lear, 2.2.194-8) there is more than one tempo change:

Here, if we extend the musical analogy, we have a relatively lento two-part exchange, then an allegrissimo four-part exchange, then a two-part allegro, and finally a two-part rallentando, leading into Lear’s next speech. The metrical discipline, in such cases, is doing far more than providing an auditory rhythm: it is motivating the dynamic of the interaction between the characters.

Discourse interaction

The aim of stylistic analysis is ultimately to explain the choices that a person makes, in speaking or writing. If I want to express the thought that ‘I have two loves’ there are many ways in which I can do it, in addition to that particular version. I can alter the sentence structure (It’s two loves that I have), the word structure (I’ve two loves), the word order (Two loves I have), or the vocabulary (I’ve got two loves, I love two people), or opt for a more radical rephrasing (There are two loves in my life). The choice will be motivated by the user’s sense of the different nuances, emphases, rhythms, and sound patterns carried by the words. In casual usage, little thought will be given to the merits of the alternatives: conveying the ‘gist’ is enough. But in an artistic construct, each linguistic decision counts, for it affects the structure and interpretation of the whole. It is rhythm and emphasis that govern the choice made for the opening line of Sonnet 144: ‘Two loves I have, of comfort and despair’. As the aim is to write a sonnet, it is critical that the choice satisfies the demands of the metre; but there is more to the choice than rhythm, for I have two loves would also work. The inverted word order conveys two other effects: it places the theme of the poem in the forefront of our attention, and it gives the line a semantic balance, locating the specific words at the beginning and the end.

Evaluating the literary or dramatic impact of the effects conveyed by the various alternatives can take up many hours of discussion; but the first step in stylistic analysis is to establish what those effects are. The clearest answers emerge when there is a frequent and perceptible contrast between pairs of options, and this is the best way of approaching the analysis of discourse interaction in the plays. Examples include the choice between the pronouns thou and you and the choice between verse and prose.

THE CHOICE BETWEEN thou AND you

In Old English, thou (thee, thine, etc.) was singular and you was plural. But during the thirteenth century, you started to be used as a polite form of the singular – probably because people copied the French way of talking, where vous was used in that way. English then became like French, which has tu and vous both possible for singulars; and that allowed a choice. The norm was for you to be used by inferiors to superiors – such as children to parents, or servants to masters, and thou would be used in return. But thou was also used to express special intimacy, such as when addressing God. It was also used when the lower classes talked to each other. The upper classes used you to each other, as a rule, even when they were closely related.

So, when someone changes from thou to you in a conversation, or the other way round, it conveys a different pragmatic force. It will express a change of attitude, or a new emotion or mood. As an illustration, we can observe the switching of pronouns as an index of Regan’s state of mind when she tries to persuade Oswald to let her see Goneril’s letter (The Tragedy of King Lear, 4.4.119-40). She begins with the expected you, but switches to thee when she tries to use her charm:

REGAN

Why should she write to Edmond? Might not you

Transport her purposes by word? Belike—

Some things—I know not what. I’ll love thee much:

Let me unseal the letter.

OSWALD

Madam, I had rather—

REGAN

I know your lady does not love her husband.

Oswald’s hesitation makes her return to you again, and she soon dismisses him in an abrupt short line with this pronoun; but when he responds enthusiastically to her next request she opts again for thee:

I pray desire her call her wisdom to her.

So, fare you well.

If you do chance to hear of that blind traitor,

Preferment falls on him that cuts him off.

OSWALD

Would I could meet him, madam. I should show

What party I do follow.

REGAN

Fare thee well.

Here we have thee being used as an index of warmth of feeling – quite the reverse of the insulting use of thou between nobles noted earlier. Similarly, thou-forms can be used as an index of intimacy, as when Graziano and Bassanio meet (The Merchant of Venice, 2.2.170-90). They begin with the expected exchange of you:

GRAZIANO

I have a suit to you.

BASSANIO

You have obtained it.

GRAZIANO

You must not deny me. I must go with you to

Belmont.

BASSANIO

Why then, you must.

But Bassanio then takes Graziano on one side and gives him some advice. The more intimate tone immediately motivates a pronoun switch: ‘But hear thee, Graziano, I Thou art too wild, too rude and bold of voice’. And he continues with thou-forms for the rest of his speech. When Graziano swears he will reform, the relationship returns to the normal public mode of address:

BASSANIO Well, we shall see your bearing.

And they you each other for the rest of the scene.

THE CHOICE BETWEEN VERSE AND PROSE

Shakespeare’s practice in using verse or prose varied greatly at different stages in his career. There are plays written almost entirely in verse (e.g. Richard II) and others almost entirely in prose (e.g. The Merry Wives of Windsor), but most plays display a mixture of the two modes, with certain types of situation or character prompting one or the other. Verse – whether rhymed or unrhymed (‘blank’ verse) – is typically associated with a ‘high style’ of language, prose with a ‘low style’. This is partly a matter of class distinction. High-status people, such as nobles and generals, tend to use the former; low-status people, such as clowns and tavern-frequenters, tend to use the latter (though in a ‘verse play’, such as Richard II, even the gardeners talk verse). Upper-class people also have an ability to accommodate to those of lower class, using prose, should occasion arise. ‘I can drink with any tinker in his own language during my life’, says Prince Harry to Poins (I Henry IV, 2.5.18-19). And lower-class people who move in court circles, such as messengers and guards, are able to use a poetic style when talking to their betters. This lower-class ability to accommodate upwards can take listeners by surprise. The riotous citizens at the beginning of Coriolanus all use prose, but when Menenius reasons with them, in elegant verse, the spokesman gradually slips into verse too – much to Menenius’ amazement: ‘Fore me, this fellow speaks!’ (1.1.118).

The distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ style is also associated with subject matter. For example, expressions of romantic love are made in verse, regardless of the speaker’s social class.

If thou rememberest not the slightest folly

That ever love did make thee run into,

Thou hast not loved.

Or if thou hast not sat as I do now,

Wearing thy hearer in thy mistress’ praise,

Thou hast not loved.

This elegant plaint is from Silvius, a shepherd (As You Like It, 2.4.311-6), but it could have come from any princely lover. Conversely, ‘low’ subject matter, such as ribaldry, tends to motivate prose, even when spoken by upper-class people. When Hamlet meets Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Hamlet, 2.2.226), they exchange a prose greeting, then the two visitors open the conversation at a formal, poetic level. But Hamlet brings them down to earth with a jocular comment, and the ribald follow-up confirms that the conversation is to stay in prose. (It is a widespread editorial practice to print prose lines immediately after the speaker’s name, and verse lines beneath it. However, discrepancies between different editions show that the distinction is not always easy to draw.)

HAMLET My ex’llent good friends. How dost thou, Guildenstern? Ah, Rosencrantz—good lads, how do ye both?

ROSENCRANTZ

As the indifferent children of the earth.

GUILDENSTERN

Happy in that we are not over-happy,

On Fortune’s cap we are not the very button.

HAMLET Nor the soles of her shoe?

ROSENCRANTZ Neither, my lord.

HAMLET Then you live about her waist, or in the middle of her favour?

GUILDENSTERN Faith, her privates we.

In a play where the upper-class protagonists tend to speak prose, it takes moments of special drama to motivate a switch to verse, as in the scene when Claudio accuses Hero of being unfaithful (Much Ado About Nothing, 4.1). Beatrice uses nothing but prose in the first half of this play, but, left alone after overhearing the news that Benedick loves her, she expresses her newly heightened sensibilities in ten lines of rhyming verse (3.1.107-16). In Othello (1.3), the Duke of Venice speaks only verse in debating the question of Othello’s love for Desdemona, but when he has to recount the affairs of state, he resorts to prose (1.3.220-7).

These norms explain only a proportion of the ways that verse and prose are used in the plays. There are many instances where people switch between one and the other, and when they do we must assume it is for a reason. Sane adults do not change their style randomly. For example, in Much Ado About Nothing (2.3.235-41), Benedick is tricked into thinking that Beatrice loves him, so when he next meets her he uses verse as a sign of the new relationship. Beatrice, however, at this point unaware of any such thing, rejects the stylistic overture, and her rebuttal forces Benedick to retreat into prose:

BEATRICE Against my will I am sent to bid you come in to dinner.

BENEDICK

Fair Beatrice, I thank you for your pains.

BEATRICE I took no more pains for those thanks than you would take pains to thank me. If it had been painful I would not have come.

BENEDICK You take pleasure, then, in the message?

This is prose as put-down. And we see it again in the opening scene of Timon of Athens (1.1.179-91), where Timon and his flatterers have been engaged in a genteel conversation in verse about social and artistic matters. The arrival of the cynical Apemantus lowers the tone, and – anticipating trouble – the speakers switch into prose:

TIMON

Look who comes here.

Will you be chid?

JEWELLER We will bear, with your lordship.

MERCHANT He’ll spare none.

Timon tries to maintain the high tone by addressing Apemantus in verse, and Apemantus shows he is capable of the high style by responding in kind; but his acerbic comments introduce a low tone which forces all to retreat into prose:

TIMON

Good morrow to thee, gentle Apemantus.

APEMANTUS

Till I be gentle, stay thou for thy good morrow—

When thou art Timon’s dog, and these knaves

honest.

TIMON

Why dost thou call them knaves? Thou know’st

them not.

APEMANTUS Are they not Athenians?

TIMON Yes.

APEMANTUS Then I repent not.

JEWELLER You know me, Apemantus?

APEMANTUS

Thou know’st I do. I called thee by thy name.

The one-line poetic riposte to the jeweller, under the circumstances, has to be seen as a mocking adoption of the high style.

If verse is a sign of high style, then we will expect aspirants to power to use it to make their case, and disguised nobility to use it when their true character needs to appear. An example of the first is in Contention, where Jack Cade is claiming to be one of Mortimer’s two sons, and thus the heir to the throne. He and his fellow rebels speak to each other in prose. When Stafford and his brother arrive, they show their social distance by addressing the rebels in verse. But Cade is playing his part well, and responds in verse, as would befit someone with breeding. His rhetoric is so impressive, indeed, that it even influences the Butcher, who responds uncharacteristically with a line of verse of his own (4.2.140-5):

The elder of them, being put to nurse,

Was by a beggar-woman stol’n away,

And, ignorant of his birth and parentage,

Became a bricklayer when he came to age.

His son am I—deny it an you can.

BUTCHER

Nay ‘tis too true—therefore he shall be king.

An example of disguised nobility is in Pericles (19.25 ff.), when governor Lysimachus arrives at a brothel with the intent of seducing Marina, whom he thinks to be a prostitute. The conversation between him, Marina, and the brothel-keepers is entirely in prose. Left alone with her, however, Lysimachus begins courteously in verse, and is taken aback when Marina shows she can respond in the same way, and moreover use the mode to powerful rhetorical effect. ‘I did not think | Thou couldst have spoke so well’, he says, as he repents of his intention. Marina knows the power of poetry, and uses it again later in the scene to persuade Boult to take her side.

The switch from verse to prose, or vice versa, can also give us insight into the state of mind of a speaker. In the case of Pandarus (Troilus and Cressida, 4.2.51-6), the switch to prose signals confusion. Aeneas calls on Pandarus early one morning, urgently needing to talk to Troilus, who has secretly spent the night with Cressida. The formal encounter and serious subject matter motivate verse. But Aeneas’ directness catches Pandarus off-guard, who confusedly lapses into prose:

AENEAS

Is not Prince Troilus here?

PANDARUS

Here? What should he do here?

AENEAS

Come, he is here, my lord. Do not deny him.

It doth import him much to speak with me.

PANDARUS Is he here, say you? It’s more than I know,

I’ll be sworn. For my part, I came in late. What

should he do here?

Something similar happens to Polonius, when he gets confused (Hamlet, 2.1.49-51). He has been giving Reynaldo a series of instructions in verse, but then he loses the track of what he is saying:

And then, sir, does a this—a does—

what was I about to say? By the mass, I was about to

say something. Where did I leave?

And Reynaldo reminds him, in verse.

In the case of Benvolio and Mercutio, meeting in Romeo and Juliet (3.1.1-10), we have two very different states of mind signalled by the two modes. The temperate Benvolio begins in verse, but he cannot withstand the onslaught of Mercutio’s prose:

BENVOLIO

I pray thee, good Mercutio, let’s retire.

The day is hot, the Capels are abroad,

And if we meet we shall not scape a brawl,

For now, these hot days, is the mad blood stirring.

MERCUTIO Thou art like one of these fellows that, when he enters the confines of a tavern, claps me his sword upon the table and says ‘God send me no need of thee’, and by the operation of the second cup, draws him on the drawer when indeed there is no need.

BENVOLIO Am I like such a fellow?

And they continue in prose.

In another meeting, between Cassius and Brutus in Julius Caesar (4.2.80-8), the switching between verse and prose acts as a guide to the temperature of the interaction. They are accusing each other of various wrongs. For the most part they speak verse to each other; but when they are on the verge of losing their temper, they switch into prose:

CASSIUS Brutus, bay not me.

I’ll not endure it. You forget yourself

To hedge me in. I am a soldier, I,

Older in practice, abler than yourself

To make conditions.

BRUTUS Go to, you are not, Cassius.

CASSIUS I am.

BRUTUS I say you are not.

CASSIUS

Urge me no more, I shall forget myself.

And Cassius resumes in verse, until once again, Brutus drives him to explode into prose (4.2.112-118):

CASSIUS

When Caesar lived he durst not thus have moved me.

BRUTUS

Peace, peace; you durst not so have tempted him.

CASSIUS I durst not?

BRUTUS No.

CASSIUS What, durst not tempt him?

BRUTUS For your life you durst not.

CASSIUS

Do not presume too much upon my love.

People were evidently very sensitive to these modality changes, and sometimes the text explicitly recognizes the contrasts involved. In Antony and Cleopatra, the summit meeting between Caesar, Antony, and their advisors is carried on in formal verse. But when Enobarbus intervenes with a down-to-earth comment in prose, he receives a sharp rebuke from Antony: ‘Thou art a soldier only. Speak no more’ (2.2.112). And in As You Like It, Orlando arrives in the middle of a prose conversation in which Jaques is happily expounding his melancholy to Ganymede (aka Rosalind). Orlando addresses Ganymede with a line of verse, which immediately upsets Jaques: ‘Nay then, God b‘wi’you an you talk in blank verse’ (4.1.29-30). And Jaques promptly leaves.