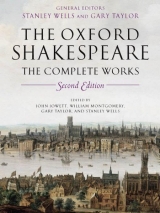

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 52 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

No rightful plea might plead for justice there.

His scarlet lust came evidence to swear

That my poor beauty had purloined his eyes;

And when the judge is robbed, the prisoner dies.

‘O teach me how to make mine own excuse,

Or at the least this refuge let me find:

Though my gross blood be stained with this abuse,

Immaculate and spotless is my mind.

That was not forced, that never was inclined

To accessory yieldings, but still pure

Doth in her poisoned closet yet endure.’

Lo, here the hopeless merchant of this loss,

With head declined and voice dammed up with woe,

With sad set eyes and wreathed arms across,

From lips new waxen pale begins to blow

The grief away that stops his answer so;

But wretched as he is, he strives in vain.

What he breathes out, his breath drinks up again.

As through an arch the violent roaring tide

Outruns the eye that doth behold his haste,

Yet in the eddy boundeth in his pride

Back to the strait that forced him on so fast,

In rage sent out, recalled in rage being past;

Even so his sighs, his sorrows, make a saw,

To push grief on, and back the same grief draw.

Which speechless woe of his poor she attendeth,

And his untimely frenzy thus awaketh:

‘Dear lord, thy sorrow to my sorrow lendeth

Another power; no flood by raining slaketh.

My woe too sensible thy passion maketh,

More feeling-painful. Let it then suffice

To drown on woe one pair of weeping eyes.

‘And for my sake, when I might charm thee so,

For she that was thy Lucrece, now attend me.

Be suddenly revenged on my foe—

Thine, mine, his own. Suppose thou dost defend me

From what is past. The help that thou shalt lend me

Comes all too late, yet let the traitor die,

For sparing justice feeds iniquity.

‘But ere I name him, you fair lords,’ quoth she,

Speaking to those that came with Collatine,

‘Shall plight your honourable faiths to me

With swift pursuit to venge this wrong of mine;

For ’tis a meritorious fair design

To chase injustice with revengeful arms.

Knights, by their oaths, should right poor ladies’

harms.’

At this request with noble disposition

Each present lord began to promise aid,

As bound in knighthood to her imposition,

Longing to hear the hateful foe bewrayed.

But she that yet her sad task hath not said

The protestation stops. ‘O speak,’ quoth she;

‘How may this forced stain be wiped from me?

‘What is the quality of my offence,

Being constrained with dreadful circumstance?

May my pure mind with the foul act dispense,

My low-declined honour to advance?

May any terms acquit me from this chance?

The poisoned fountain clears itself again,

And why not I from this compelled stain?’

With this they all at once began to say

Her body’s stain her mind untainted clears,

While with a joyless smile she turns away

The face, that map which deep impression bears

Of hard misfortune, carved in it with tears.

‘No, no,’ quoth she, ‘no dame hereafter living

By my excuse shall claim excuse’s giving.’

Here with a sigh as if her heart would break

She throws forth Tarquin’s name. ‘He, he,’ she says—

But more than he her poor tongue could not speak,

Till after many accents and delays,

Untimely breathings, sick and short essays,

She utters this: ‘He, he, fair lords, ’tis he

That guides this hand to give this wound to me.’

Even here she sheathed in her harmless breast

A harmful knife, that thence her soul unsheathed.

That blow did bail it from the deep unrest

Of that polluted prison where it breathed.

Her contrite sighs unto the clouds bequeathed

Her winged sprite, and through her wounds doth fly

Life’s lasting date from cancelled destiny.

Stone-still, astonished with this deadly deed

Stood Collatine and all his lordly crew,

Till Lucrece’ father that beholds her bleed

Himself on her self-slaughtered body threw;

And from the purple fountain Brutus drew

The murd’rous knife; and as it left the place

Her blood in poor revenge held it in chase,

And bubbling from her breast it doth divide

In two slow rivers, that the crimson blood

Circles her body in on every side,

Who like a late-sacked island vastly stood,

Bare and unpeopled in this fearful flood.

Some of her blood still pure and red remained,

And some looked black, and that false Tarquinstained.

About the mourning and congealed face

Of that black blood a wat’ry rigol goes,

Which seems to weep upon the tainted place;

And ever since, as pitying Lucrece’ woes,

Corrupted blood some watery token shows;

And blood untainted still doth red abide,

Blushing at that which is so putrefied.

‘Daughter, dear daughter,’ old Lucretius cries,

‘That life was mine which thou hast here deprived.

If in the child the father’s image lies,

Where shall I live now Lucrece is unlived?

Thou wast not to this end from me derived.

If children predecease progenitors,

We are their offspring, and they none of ours.

‘Poor broken glass, I often did behold

In thy sweet semblance my old age new born;

But now that fair fresh mirror, dim and old,

Shows me a bare-boned death by time outworn.

O, from thy cheeks my image thou hast torn,

And shivered all the beauty of my glass,

That I no more can see what once I was.

‘O time, cease thou thy course and last no longer,

If they surcease to be that should survive!

Shall rotten death make conquest of the stronger,

And leave the falt’ring feeble souls alive?

The old bees die, the young possess their hive.

Then live, sweet Lucrece, live again and see

Thy father die, and not thy father thee.’

By this starts Collatine as from a dream,

And bids Lucretius give his sorrow place;

And then in key-cold Lucrece’ bleeding stream

He falls, and bathes the pale fear in his face,

And counterfeits to die with her a space,

Till manly shame bids him possess his breath,

And live to be revenged on her death.

The deep vexation of his inward soul

Hath served a dumb arrest upon his tongue,

Who, mad that sorrow should his use control,

Or keep him from heart-easing words so long,

Begins to talk; but through his lips do throng

Weak words, so thick come in his poor heart’s aid

That no man could distinguish what he said.

Yet sometime ‘Tarquin’ was pronounced plain,

But through his teeth, as if the name he tore.

This windy tempest, till it blow up rain,

Held back his sorrow’s tide to make it more.

At last it rains, and busy winds give o’er.

Then son and father weep with equal strife

Who should weep most, for daughter or for wife.

The one doth call her his, the other his,

Yet neither may possess the claim they lay.

The father says ‘She’s mine’; ‘O, mine she is,’

Replies her husband, ‘do not take away

My sorrow’s interest; let no mourner say

He weeps for her, for she was only mine,

And only must be wailed by Collatine.’

‘O,’ quoth Lucretius, ‘I did give that life

Which she too early and too late hath spilled.’

‘Woe, woe,’ quoth Collatine, ‘she was my wife.

I owed her, and ’tis mine that she hath killed.’

‘My daughter’ and ‘my wife’ with clamours filled

The dispersed air, who, holding Lucrece’ life,

Answered their cries, ‘my daughter’ and ‘my wife’.

Brutus, who plucked the knife from Lucrece’ side,

Seeing such emulation in their woe

Began to clothe his wit in state and pride,

Burying in Lucrece’ wound his folly’s show.

He with the Romans was esteemed so

As silly jeering idiots are with kings,

For sportive words and utt’ring foolish things.

But now he throws that shallow habit by

Wherein deep policy did him disguise,

And armed his long-hid wits advisedly

To check the tears in Collatinus’ eyes.

‘Thou wronged lord of Rome,’ quoth he, ‘arise.

Let my unsounded self, supposed a fool,

Now set thy long-experienced wit to school.

‘Why, Collatine, is woe the cure for woe?

Do wounds help wounds, or grief help grievous deeds?

Is it revenge to give thyself a blow

For his foul act by whom thy fair wife bleeds?

Such childish humour from weak minds proceeds;

Thy wretched wife mistook the matter so

To slay herself, that should have slain her foe.

‘Courageous Roman, do not steep thy heart

In such relenting dew of lamentations,

But kneel with me, and help to bear thy part

To rouse our Roman gods with invocations

That they will suffer these abominations—

Since Rome herself in them doth stand disgraced—

By our strong arms from forth her fair streets chased.

‘Now by the Capitol that we adore,

And by this chaste blood so unjustly stained,

By heaven’s fair sun that breeds the fat earth’s store,

By all our country rights in Rome maintained,

And by chaste Lucrece’ soul that late complained

Her wrongs to us, and by this bloody knife,

We will revenge the death of this true wife.’

This said, he struck his hand upon his breast,

And kissed the fatal knife to end his vow,

And to his protestation urged the rest,

Who, wond’ring at him, did his words allow.

Then jointly to the ground their knees they bow,

And that deep vow which Brutus made before

He doth again repeat, and that they swore.

When they had sworn to this advised doom

They did conclude to bear dead Lucrece thence,

To show her bleeding body thorough Rome,

And so to publish Tarquin’s foul offence;

Which being done with speedy diligence,

The Romans plausibly did give consent

To Tarquin’s everlasting banishment.

EDWARD III

BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND OTHERS

FIRST heard of in the Stationers’ Register for I December 1595, The Reign of King Edward the Third was published anonymously in the following year, with the statement that it had been ‘sundry times played about the City of London’. As was usual, there are no act and scene divisions; we divide it only into scenes. It could have been written at any time between the Armada of 1588 and 1595. Like other plays of this period, including Shakespeare’s I Henry VI, Richard II, and King John, it is composed entirely in verse, much of it formal and rhetorical in style. Shakespeare seems at least to have known the play, since a historical error placing King David of Scotland among Edward’s prisoners at Calais (10.40-56, 18.63.1) occurs also in Henry V (1.2.160-2). The play’s omission from the First Folio is good presumptive evidence against Shakespeare’s sole authorship. It was, however, attributed to him in a totally unreliable catalogue of 1656; better worth taking seriously is the attribution to Shakespeare by Edward Capell, expressed in 1760. Since then various scholars have proposed that Shakespeare wrote at least the scenes involving the Countess of Salisbury (Scene 2, Scene 3). When the Oxford edition first appeared, its editors remarked that ‘if we had attempted a thorough reinvestigation of candidates for inclusion in the early dramatic canon, it would have begun with Edward III’ (Textual Companion, p. 137). Since then intensive application of stylometric and other tests of authorship, along with an increased willingness to acknowledge that Shakespeare collaborated with other writers, especially early and late in his career, has strengthened the case for including it among the collected works. We believe, however, that Shakespeare was responsible only for Scene 2 (from the entrance of Edward III) and Scene 3, and for Scene 12 (which includes a Hamlet-like meditation on the inevitability of death), and possibly Scene 13, and that one or more other authors wrote the rest of the play.

The play’s treatment of history, deriving principally from Lord Berners’s translation (1535) of Froissart’s Chronicles, is loose. As with Henry V, the opening episode shows the English king seeking reassurance about his claims to the throne of France. Lorraine’s subsequent demand that Edward swear allegiance to the French king meets with derision. Attention turns to England’s relations with Scotland, where King David, France’s ally, has besieged the castle of Roxburgh, imprisoning the Countess of Salisbury. Edward instructs his son Edward (Ned) the Black Prince to raise troops against France; Edward himself will march against the Scots. At Roxburgh the King rescues and attempts to seduce the Countess, who is also desired by King David and Sir William Douglas. In the principal scenes ascribed to Shakespeare, the enraptured King expresses his passion in attractively lyrical verse recalling that of The Two Gentlemen of Verona. He attempts to persuade the Earl of Warwick, the Countess’s father, to further his suit, but the Countess, virtuous (and married), repudiates his adulterous desires, threatening to kill herself if he persists. Penitent, he reverts to the French conflict. This, presented in episodes of ambitious rhetoric rather than of violent action, reaches its first climax in young Edward’s conquest over the King of Bohemia, for which his father knights him. Edward’s queen, Philippa, who with her followers has overcome the Scots, joins him, and persuades him to show mercy to the burghers of the besieged town of Calais. Young Edward, believed dead, is revealed as the conqueror of the French, and the play ends with a jingoistic English triumph. It has had a few modern productions, including one by the Royal Shakespeare Company in

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

The English

KING EDWARD III

QUEEN PHILIPPA, his wife

Edward, PRINCE OF WALES, their eldest son

The EARL OF SALISBURY

The COUNTESS OF SALISBURY, his wife

The EARL OF WARWICK, the Countess’s father

Sir William de MONTAGUE, Salisbury’s nephew

The EARL OF DERBY

Sir James AUDLEY

Henry, Lord PERCY

John COPLAND, an esquire, later knighted

LODOWICK, King Edward’s secretary

Two SQUIRES

A HERALD to King Edward from the Prince of Wales Four heralds who bear the Prince of Wales’s armour Soldiers

Allied with the English

Robert, COMTE D’ARTOIS and Earl of Richmond

Jean, COMTE DE MONTFORT, later Duc de Bretagne

GOBIN de Grace, a French Prisoner

The French

Jean II de Valois, KING OF FRANCE

Prince Charles, Jean’s eldest son, Duc de Normandie, the DAUPHIN

PRINCE PHILIPPE, Jean’s younger son

The DUC DE LORRAINE

VILLIERS, a prisoner sent as an envoy by the Earl of Salisbury to the Dauphin

The CAPTAIN OF CALAIS

Another FRENCH CAPTAIN

A MARINER

Three HERALDS to the Prince of Wales from the King of France, the Dauphin and Prince Philippe

Six POOR MEN, residents of Calais

Six SUPPLICANTS, wealthy merchants and citizens of Calais

Five other FRENCHMEN

A FRENCIIWOMAN with two children

Soldiers

Allied with the French

The KING OF BOHEMIA

A POLISH CAPTAIN

Polish and Muscovite soldiers

David II, KING OF SCOTLAND

Sir William DOUGLAS

Two Scottish MESSENGERS

The Reign of King Edward the Third

Sc. 1 Enter King Edward, the Earl of Derby, the Earl of Warwick,⌉ Edward Prince of Wales, Lord Audley and the Comte d’Artois

KING EDWARD

Robert of Artois, banished though thou be

From France thy native country, yet with us

Thou shalt retain as great a seigniory:

For we create thee Earl of Richmond here.

And now go forwards with our pedigree:

Who next succeeded King Philippe of Beau?

COMTE D’ARTOIS

Three sons of his, which all successively

Did sit upon their father’s regal throne,

Yet died and left no issue of their loins.

KING EDWARD

But was my mother sister unto those?

COMTE D’ARTOIS

She was, my lord, and only Isabel

Was all the daughters that this Philippe had,

Whom afterward your father took to wife.

And from the fragrant garden of her womb

Your gracious self, the flower of Europe’s hope,

Derived is inheritor to France.

But note the rancour of rebellious minds:

When thus the lineage of Beau was out

The French obscured your mother’s privilege

And, though she were the next of blood, proclaimed

Jean of the house of Valois now their king.

The reason was, they say, the realm of France

Replete with princes of great parentage

Ought not admit a governor to rule

Except he be descended of the male.

And that’s the special ground of their contempt

Wherewith they study to exclude your grace.

KING EDWARD

But they shall find that forged ground of theirs

To be but dusty heaps of brittle sand.

COMTE D’ARTOIS

Perhaps it will be thought a heinous thing

That I, a Frenchman, should discover this.

But heaven I call to record of my vows:

It is not hate nor any private wrong,

But love unto my country and the right

Provokes my tongue thus lavish in report.

You are the lineal watchman of our peace,

And Jean of Valois indirectly climbs.

What then should subjects but embrace their king?

Ah, wherein may our duty more be seen

Than striving to rebate a tyrant’s pride

And place thee, the true shepherd of our commonwealth?

KING EDWARD

This counsel, Artois, like to fruitful showers,

Hath added growth unto my dignity,

And by the fiery vigour of thy words

Hot courage is engendered in my breast,

Which heretofore was raked in ignorance

But now doth mount with golden wings of fame

And will approve fair Isabel’s descent,

Able to yoke their stubborn necks with steel

That spurn against my sovereignty in France.

Sound a horn

A messenger. Lord Audley, know from whence.

⌈Enter a messenger, the Duc de Lorraine⌉

AUDLEY

The Duke of Lorraine, having crossed the seas,

Entreats he may have conference with your highness.

KING EDWARD

Admit him, lords, that we may hear the news.

(To Lorraine) Say, Duke of Lorraine, wherefore art thou come? 55

DUC DE LORRAINE

The most renowned prince, King Jean of France,

Doth greet thee, Edward, and by me commands

That, forsomuch as by his liberal gift

The Guienne dukedom is entailed to thee,

Thou do him lowly homage for the same.

And for that purpose, here I summon thee

Repair to France within these forty days

That there, according as the custom is,

Thou mayst be sworn true liegeman to our king;

Or else thy title in that province dies

And he himself will repossess the place.

KING EDWARD

See how occasion laughs me in the face!

No sooner minded to prepare for France

But straight I am invited—nay, with threats,

Upon a penalty, enjoined to come!

‘Twere but a childish part to say him nay.

Lorraine, return this answer to thy lord:

I mean to visit him as he requests.

But how? Not servilely disposed to bend,

But like a conqueror to make him bow.

His lame unpolished shifts are come to light,

And truth hath pulled the vizard from his face

That set a gloss upon his arrogance.

Dare he command a fealty in me?

Tell him the crown that he usurps is mine,

And where he sets his foot he ought to kneel.

’Tis not a petty dukedom that I claim

But all the whole dominions of the realm

Which if, with grudging, he refuse to yield

I’ll take away those borrowed plumes of his,

And send him naked to the wilderness.

DUC DE LORRAINE

Then, Edward, here, in spite of all thy lords,

I do pronounce defiance to thy face.

PRINCE OF WALES

Defiance, Frenchman? We rebound it back

Even to the bottom of thy master’s throat!

And, be it spoke with reverence of the King,

My gracious father, and these other lords,

I hold thy message but as scurrilous,

And him that sent thee like the lazy drone

Crept up by stealth unto the eagle’s nest,

From whence we’ll shake him with so rough a storm

As others shall be warned by his harm.

EARL OF WARWICK (to Lorraine)

Bid him leave off the lion’s case he wears

Lest, meeting with the lion in the field,

He chance to tear him piecemeal for his pride.

COMTE D’ARTOIS (to Lorraine)

The soundest counsel I can give his grace

Is to surrender ere he be constrained.

A voluntary mischief hath less scorn

Than when reproach with violence is borne.

DUC DE LORRAINE

Regenerate traitor, viper to the place

Where thou wast fostered in thine infancy!

Bear’st thou a part in this conspiracy?

⌈Lorraine⌉ draws his sword

KING EDWARD ⌈drawing his sword⌉

Lorraine, behold the sharpness of this steel:

Fervent desire that sits against my heart

Is far more thorny-pricking than this blade

That, with the nightingale, I shall be scarred

As oft as I dispose myself to rest

Until my colours be displayed in France.

This is thy final answer. So be gone.

DUC DE LORRAINE

It is not that, nor any English brave,

Afflicts me so, as doth his poisoned view:

That is most false, should most of all be true. Exit

KING EDWARD

Now, lords, our fleeting barque is under sail,

Our gage is thrown, and war is soon begun,

But not so quickly brought unto an end.

Enter Sir William Montague

But wherefore comes Sir William Montague?

(To Montague) How stands the league between the Scot and us?

MONTAGUE

Cracked and dissevered, my renowned lord.

The treacherous King no sooner was informed

Of your withdrawing of your army back

But straight, forgetting of his former oath,

He made invasion on the bordering towns.

Berwick is won, Newcastle spoiled and lost,

And now the tyrant hath begirt with siege

The Castle of Roxburgh, where, enclosed,

The Countess Salisbury is like to perish.

KING EDWARD (to Warwick)

That is thy daughter, Warwick, is it not?

Whose husband hath in Bretagne served so long

About the planting of Lord Montfort there?

EARL OF WARWICK It is, my lord.

KING EDWARD

Ignoble David, hast thou none to grieve

But seely ladies with thy threat’ning arms?

But I will make you shrink your snaily horns.

(To Audley) First, therefore, Audley, this shall be thy charge:

Go levy footmen for our wars in France.

(To the Prince of Wales) And, Ned, take muster of our men-at-arms.

In every shire elect a several band.

Let them be soldiers of a lusty spirit,

Such as dread nothing but dishonour’s blot.

Be wary therefore, since we do commence

A famous war, and with so mighty a nation.

(To Derby) Derby, be thou ambassador for us

Unto our father-in-law, the Earl of Hainault.

Make him acquainted with our enterprise,

And likewise will him, with our own allies

That are in Flanders, to solicit, too,

The Emperor of Almagne in our name.

Myself, whilst you are jointly thus employed,

Will, with these forces that I have at hand,

March and once more repulse the traitorous Scot.

But sirs, be resolute. We shall have wars

On every side. (To the Prince of Wales) And, Ned, thou must begin

Now to forget thy study and thy books,

And ure thy shoulders to an armour’s weight.

PRINCE OF WALES

As cheerful sounding to my youthful spleen

This tumult is of war’s increasing broils,

As at the coronation of a king

The joyful clamours of the people are

When ‘Ave Caesar’ they pronounce aloud.

Within this school of honour I shall learn

Either to sacrifice my foes to death,

Or, in a rightful quarrel, spend my breath.

Then cheerfully forward, each a several way.

In great affairs ’tis naught to use delay. Exeunt