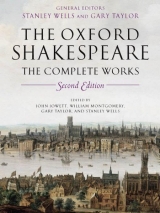

Текст книги "William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition"

Автор книги: William Shakespeare

Жанр:

Литературоведение

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 214 (всего у книги 250 страниц)

THE TRAGEDY OF KING LEAR

THE FOLIO TEXT

THE text of King Lear given here represents the revision made probably three or four years after the first version had been written and performed; it is based on the text printed in the 1623 Folio. This is the more obviously theatrical text. It makes a number of significant cuts, amounting to some 300 lines. The most conspicuous ones are the dialogue in which Lear’s Fool implicitly calls his master a fool (Quarto Sc. 4, 136―51); Kent’s account of the French invasion of England (Quarto Sc. 8, 21―33); Lear’s mock-trial, in his madness, of his daughters (Quarto Sc. 13, 13―52); Edgar’s generalizing couplets at the end of that scene (Quarto Sc. 13, 97―110); the brief, compassionate dialogue of two of Gloucester’s servants after his blinding (Quarto Sc. 14, 97―106); parts of Albany’s protest to Goneril about the sisters’ treatment of Lear (in Quarto Sc. 16); the entire scene (Quarto Sc. 17) in which a Gentleman tells Kent of Cordelia’s grief on hearing of her father’s condition; the presence of the Doctor and the musical accompaniment to the reunion of Lear and Cordelia (Quarto Sc. 21); and Edgar’s account of his meeting with Kent in which Kent’s ’strings of life | Began to crack’ (Quarto Sc. 24, 201―18). The Folio also adds about 100 lines that are not in the Quarto—mostly in short passages, including Kent’s statement that Albany and Cornwall have servants who are in the pay of France (3.1.13―20), Merlin’s prophecy spoken by the Fool at the end of 3.2, and the last lines of both the Fool and Lear. In addition, several speeches are differently assigned, and there are many variations in wording.

The reasons for these variations, and their effect on the play, are to some extent matters of speculation and of individual interpretation. Certainly they streamline the play’s action, removing some reflective passages, particularly at the ends of scenes. They affect the characterization of, especially, Edgar, Albany, and Kent, and there are significant differences in the play’s closing passages. Structurally the principal differences lie in the presentation of the military actions in the later part of the play; in the Folio-based text Cordelia is more clearly in charge of the forces that come to Lear’s assistance, and they are less clearly a French invasion force. The absence from this text of passages that appeared in the 1608 text implies no criticism of them in themselves. The play’s revision may have been dictated in whole or in part by theatrical exigencies, or it may have emerged from Shakespeare’s own dissatisfaction with what he had first written. Each version has its own integrity, which is distorted by the practice, traditional since the early eighteenth century, of conflation.

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

LEAR, King of Britain

GONERIL, Lear’s eldest daughter

Duke of ALBANY, her husband

REGAN, Lear’s second daughter

Duke of CORNWALL, her husband

CORDELIA, Lear’s youngest daughter

Earl of KENT, later disguised as Caius

Earl of GLOUCESTER

EDGAR, elder son of Gloucester, later disguised as Tom o’ Bedlam

EDMOND, bastard son of Gloucester

OLD MAN, Gloucester’s tenant

CURAN, Gloucester’s retainer

Lear’s FOOL

OSWALD, Goneril’s steward

A SERVANT of Cornwall

A KNIGHT

A HERALD

A CAPTAIN

Gentlemen, servants, soldiers, attendants, messengers

The Tragedy of King Lear

1.1 Enter the Earl of Kent, the Duke of Gloucester, and Edmond

KENT I thought the King had more affected the Duke of Albany than Cornwall.

GLOUCESTER) It did always seem so to us, but now in the division of the kingdom it appears not which of the Dukes he values most; for qualities are so weighed that curiosity in neither can make choice of either’s moiety.

KENT Is not this your son, my lord?

GLOUCESTER His breeding, sir, hath been at my charge. I have so often blushed to acknowledge him that now I am brazed to’t.

KENT I cannot conceive you.

GLOUCESTER Sir, this young fellow’s mother could, whereupon she grew round-wombed and had indeed, sir, a son for her cradle ere she had a husband for her bed. Do you smell a fault?

KENT I cannot wish the fault undone, the issue of it being so proper.

GLOUCESTER But I have a son, sir, by order of law, some year older than this, who yet is no dearer in my account. Though this knave came something saucily to the world before he was sent for, yet was his mother fair, there was good sport at his making, and the whoreson must be acknowledged. (To Edmond) Do you know this noble gentleman, Edmond?

EDMOND No, my lord.

GLOUCESTER (to Edmond) My lord of Kent. Remember him hereafter as my honourable friend.

EDMOND (to Kent) My services to your lordship.

KENT I must love you, and sue to know you better.

EDMOND Sir, I shall study deserving.

GLOUCESTER (to Kent) He hath been out nine years, and away he shall again.

Sennet

The King is coming.

Enter King Lear, the Dukes of Cornwall and Albany, Goneril, Regan, Cordelia, and attendants

LEAR

Attend the lords of France and Burgundy, Gloucester.

GLOUCESTER I shall, my lord. Exit

LEAR

Meantime we shall express our darker purpose.

Give me the map there. Know that we have divided

In three our kingdom, and ’tis our fast intent

To shake all cares and business from our age,

Conferring them on younger strengths while we

Unburdened crawl toward death. Our son of Cornwall,

And you, our no less loving son of Albany,

We have this hour a constant will to publish

Our daughters’ several dowers, that future strife

May be prevented now. The princes France and

Burgundy—

Great rivals in our youngest daughter’s love—

Long in our court have made their amorous sojourn,

And here are to be answered. Tell me, my daughters—

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state—

Which of you shall we say doth love us most,

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge? Goneril,

Our eldest born, speak first.

GONERIL

Sir, I love you more than words can wield the matter;

Dearer than eyesight, space, and liberty;

Beyond what can be valued, rich or rare,

No less than life; with grace, health, beauty, honour;

As much as child e’er loved or father found;

A love that makes breath poor and speech unable.

Beyond all manner of so much I love you.

CORDELIA (aside)

What shall Cordelia speak? Love and be silent.

LEAR (to Goneril)

Of all these bounds even from this line to this,

With shadowy forests and with champaigns riched,

With plenteous rivers and wide-skirted meads,

We make thee lady. To thine and Albany’s issues

Be this perpetual.—What says our second daughter?

Our dearest Regan, wife of Cornwall?

REGAN

I am made of that self mettle as my sister,

And prize me at her worth. In my true heart

I find she names my very deed of love—

Only she comes too short, that I profess

Myself an enemy to all other joys

Which the most precious square of sense possesses,

And find I am alone felicitate

In your dear highness’ love.

CORDELIA (aside) Then poor Cordelia—

And yet not so, since I am sure my love’s

More ponderous than my tongue.

LEAR (to Regan)

To thee and thine hereditary ever

Remain this ample third of our fair kingdom,

No less in space, validity, and pleasure

Than that conferred on Goneril. (To Cordelia) Now our

joy,

Although our last and least, to whose young love

The vines of France and milk of Burgundy

Strive to be interessed: what can you say to draw

A third more opulent than your sisters? Speak.

CORDELIA Nothing, my lord.

LEAR Nothing?

CORDELIA Nothing.

LEAR

Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again.

CORDELIA

Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth. I love your majesty

According to my bond, no more nor less.

LEAR

How, how, Cordelia? Mend your speech a little

Lest you may mar your fortunes.

CORDELIA

Good my lord,

You have begot me, bred me, loved me.

I return those duties back as are right fit-

Obey you, love you, and most honour you.

Why have my sisters husbands if they say

They love you all? Haply when I shall wed

That lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry

Half my love with him, half my care and duty.

Sure, I shall never marry like my sisters.

LEAR But goes thy heart with this?

CORDELIA Ay, my good lord.

LEAR So young and so untender?

CORDELIA So young, my lord, and true.

LEAR

Let it be so. Thy truth then be thy dower;

For by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night,

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist and cease to be,

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity, and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee from this for ever. The barbarous Scythian,

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighboured, pitied, and relieved

As thou, my sometime daughter.

KENT

Good my liege—

LEAR Peace, Kent.

Come not between the dragon and his wrath.

I loved her most, and thought to set my rest

On her kind nursery. ⌈To Cordelia⌉ Hence, and avoid

my sight!—

So be my grave my peace as here I give

Her father’s heart from her. Call France. Who stirs?

Call Burgundy.

⌈Exit one or more⌉

Cornwall and Albany,

With my two daughters’ dowers digest the third.

Let pride, which she calls plainness, marry her.

I do invest you jointly with my power,

Pre-eminence, and all the large effects

That troop with majesty. Ourself by monthly course,

With reservation of an hundred knights

By you to be sustained, shall our abode

Make with you by due turn. Only we shall retain

The name and all th’addition to a king. The sway,

Revenue, execution of the rest,

Beloved sons, be yours; which to confirm,

This crownet part between you.

KENT

Royal Lear,

Whom I have ever honoured as my king,

Loved as my father, as my master followed,

As my great patron thought on in my prayers—

LEAR

The bow is bent and drawn; make from the shaft.

KENT

Let it fall rather, though the fork invade

The region of my heart. Be Kent unmannerly

When Lear is mad. What wouldst thou do, old man?

Think’st thou that duty shall have dread to speak

When power to flattery bows? To plainness honour’s

bound

When majesty falls to folly. Reserve thy state,

And in thy best consideration check

This hideous rashness. Answer my life my judgement,

Thy youngest daughter does not love thee least,

Nor are those empty-hearted whose low sounds

Reverb no hollowness.

LEAR

Kent, on thy life, no more!

KENT

My life I never held but as a pawn

To wage against thine enemies, ne’er feared to lose it,

Thy safety being motive.

LEAR

Out of my sight!

KENT

See better, Lear, and let me still remain

The true blank of thine eye.

LEAR

Now, by Apollo—

KENT

Now, by Apollo, King, thou swear’st thy gods in vain.

LEAR ⌈making to strike him⌉

O vassal! Miscreant!

ALBANY and ⌈CORDELIA⌉ Dear sir, forbear.

KENT (to Lear)

Kill thy physician, and thy fee bestow

Upon the foul disease. Revoke thy gift,

Or whilst I can vent clamour from my throat

I’ll tell thee thou dost evil.

LEAR

Hear me, recreant; on thine allegiance hear me!

That thou hast sought to make us break our vows,

Which we durst never yet, and with strained pride

To come betwixt our sentence and our power,

Which nor our nature nor our place can bear,

Our potency made good take thy reward:

Five days we do allot thee for provision

To shield thee from disasters of the world,

And on the sixth to turn thy hated back

Upon our kingdom. If on the seventh day following

Thy banished trunk be found in our dominions,

The moment is thy death. Away! By Jupiter,

This shall not be revoked.

KENT

Fare thee well, King; sith thus thou wilt appear,

Freedom lives hence, and banishment is here.

(To Cordelia) The gods to their dear shelter take thee,

maid,

That justly think’st, and hast most rightly said.

(To Goneril and Regan) And your large speeches may

your deeds approve,

That good effects may spring from words of love.

Thus Kent, O princes, bids you all adieu;

He’ll shape his old course in a country new. Exit

Flourish. Enter the Duke of Gloucester with the

King of France, the Duke of Burgundy, and attendants

⌈CORDELIA⌉

Here’s France and Burgundy, my noble lord.

LEAR My lord of Burgundy,

We first address toward you, who with this King

Hath rivalled for our daughter: what in the least

Will you require in present dower with her

Or cease your quest of love?

BURGUNDY

Most royal majesty,

I crave no more than hath your highness offered;

Nor will you tender less.

LEAR

Right noble Burgundy,

When she was dear to us we did hold her so;

But now her price is fallen. Sir, there she stands.

If aught within that little seeming substance,

Or all of it, with our displeasure pieced,

And nothing more, may fitly like your grace,

She’s there, and she is yours.

BURGUNDY

I know no answer.

LEAR

Will you with those infirmities she owes,

Unfriended, new adopted to our hate,

Dowered with our curse and strangered with our oath,

Take her or leave her?

BURGUNDY

Pardon me, royal sir.

Election makes not up in such conditions.

LEAR

Then leave her, sir; for by the power that made me,

I tell you all her wealth. (To France) For you, great King,

I would not from your love make such a stray

To match you where I hate, therefore beseech you

T‘avert your liking a more worthier way

Than on a wretch whom nature is ashamed

Almost t’acknowledge hers.

FRANCE

This is most strange,

That she whom even but now was your best object,

The argument of your praise, balm of your age,

The best, the dear’st, should in this trice of time

Commit a thing so monstrous to dismantle

So many folds of favour. Sure, her offence

Must be of such unnatural degree

That monsters it, or your fore-vouched affection

Fall into taint; which to believe of her

Must be a faith that reason without miracle

Should never plant in me.

CORDELIA (to Lear)

I yet beseech your majesty,

If for I want that glib and oily art

To speak and purpose not—since what I well intend,

I’ll do’t before I speak—that you make known

It is no vicious blot, murder, or foulness,

No unchaste action or dishonoured step

That hath deprived me of your grace and favour,

But even the want of that for which I am richer—

A still-soliciting eye, and such a tongue

That I am glad I have not, though not to have it

Hath lost me in your liking.

LEAR

Better thou

Hadst not been born than not t’have pleased me better.

FRANCE

Is it but this—a tardiness in nature,

Which often leaves the history unspoke

That it intends to do?—My lord of Burgundy,

What say you to the lady? Love’s not love

When it is mingled with regards that stands

Aloof from th’entire point. Will you have her?

She is herself a dowry.

BURGUNDY (to Lear) Royal King,

Give but that portion which yourself proposed,

And here I take Cordelia by the hand,

Duchess of Burgundy.

LEAR Nothing. I have sworn. I am firm.

BURGUNDY (to Cordelia)

I am sorry, then, you have so lost a father

That you must lose a husband.

CORDELIA

Peace be with Burgundy;

Since that respect and fortunes are his love,

I shall not be his wife.

FRANCE

Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich, being poor;

Most choice, forsaken; and most loved, despised:

Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon.

Be it lawful, I take up what’s cast away.

Gods, gods! ‘Tis strange that from their cold’st neglect

My love should kindle to inflamed respect.—

Thy dowerless daughter, King, thrown to my chance,

Is queen of us, of ours, and our fair France.

Not all the dukes of wat’rish Burgundy

Can buy this unprized precious maid of me.—

Bid them farewell, Cordelia, though unkind.

Thou losest here, a better where to find.

LEAR

Thou hast her, France. Let her be thine, for we

Have no such daughter, nor shall ever see

That face of hers again. Therefore be gone,

Without our grace, our love, our benison.—

Come, noble Burgundy. Flourish. Exeunt all but France

and the sisters

FRANCE Bid farewell to your sisters.

CORDELIA

Ye jewels of our father, with washed eyes

Cordelia leaves you. I know you what you are,

And like a sister am most loath to call

Your faults as they are named. Love well our father.

To your professed bosoms I commit him.

But yet, alas, stood I within his grace

I would prefer him to a better place.

So farewell to you both.

REGAN Prescribe not us our duty.

GONERIL Let your study

Be to content your lord, who hath received you

At fortune’s alms. You have obedience scanted,

And well are worth the want that you have wanted.

CORDELIA

Time shall unfold what pleated cunning hides,

Who covert faults at last with shame derides.

Well may you prosper.

FRANCE

Come, my fair Cordelia.

Exeunt France and Cordelia

GONERIL Sister, it is not little I have to say of what most nearly appertains to us both. I think our father will hence tonight.

REGAN That’s most certain, and with you. Next month with us.

GONERIL You see how full of changes his age is. The observation we have made of it hath been little. He always loved our sister most, and with what poor judgement he hath now cast her off appears too grossly.

REGAN ’Tis the infirmity of his age; yet he hath ever but slenderly known himself.

GONERIL The best and soundest of his time hath been but rash; then must we look from his age to receive not alone the imperfections of long-engrafted condition, but therewithal the unruly waywardness that infirm and choleric years bring with them.

REGAN Such unconstant starts are we like to have from him as this of Kent’s banishment.

GONERIL There is further compliment of leave-taking between France and him. Pray you, let us sit together. If our father carry authority with such disposition as he bears, this last surrender of his will but offend us.

REGAN We shall further think of it. GONERIL We must do something, and i’th’ heat.

Exeunt

1.2 Enter Edmond the bastard

EDMOND

Thou, nature, art my goddess. To thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why ‘bastard’? Wherefore ‘base’,

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape as true

As honest madam’s issue? Why brand they us

With ‘base’, with ‘baseness, bastardy—base, base’—

Who in the lusty stealth of nature take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth within a dull, stale, tirèd bed

Go to th’ creating a whole tribe of fops

Got ‘tween a sleep and wake? Well then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land.

Our father’s love is to the bastard Edmond

As to th’ legitimate. Fine word, ‘legitimate’.

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed

And my invention thrive, Edmond the base

Shall to th’ legitimate. I grow, I prosper.

Now gods, stand up for bastards!

Enter the Duke of Gloucester. Edmond reads a letter

GLOUCESTER

Kent banished thus, and France in choler parted,

And the King gone tonight, prescribed his power,

Confined to exhibition—all this done

Upon the gad?—Edmond, how now? What news?

EDMOND So please your lordship, none.

GLOUCESTER Why so earnestly seek you to put up that letter?

EDMOND I know no news, my lord. GLOUCESTER What paper were you reading?

EDMOND Nothing, my lord.

GLOUCESTER No? What needed then that terrible dispatch of it into your pocket? The quality of nothing hath not such need to hide itself. Let’s see. Come, if it be nothing I shall not need spectacles.

EDMOND I beseech you, sir, pardon me. It is a letter from my brother that I have not all o‘er-read; and for so much as I have perused, I find it not fit for your o’erlooking. GLOUCESTER Give me the letter, sir.

EDMOND I shall offend either to detain or give it. The contents, as in part I understand them, are to blame. GLOUCESTER Let’s see, let’s see.

EDMOND I hope for my brother’s justification he wrote this but as an assay or taste of my virtue.

He gives Gloucester a letter

GLOUCESTER (reads) ‘This policy and reverence of age makes the world bitter to the best of our times, keeps our fortunes from us till our oldness cannot relish them. I begin to find an idle and fond bondage in the oppression of aged tyranny, who sways not as it hath power but as it is suffered. Come to me, that of this I may speak more. If our father would sleep till I waked him, you should enjoy half his revenue for ever and live the beloved of your brother,

Edgar.’

Hum, conspiracy! ‘Sleep till I wake him, you should enjoy half his revenue’—my son Edgar! Had he a hand to write this, a heart and brain to breed it in? When came you to this? Who brought it?

EDMOND It was not brought me, my lord, there’s the cunning of it. I found it thrown in at the casement of my closet.

GLOUCESTER You know the character to be your brother’s?

EDMOND If the matter were good, my lord, I durst swear it were his; but in respect of that, I would fain think it were not. GLOUCESTER) It is his.

EDMOND It is his hand, my lord, but I hope his heart is not in the contents.

GLOUCESTER Has he never before sounded you in this business?

EDMOND Never, my lord; but I have heard him oft maintain it to be fit that, sons at perfect age and fathers declined, the father should be as ward to the son, and the son manage his revenue.

GLOUCESTER O villain, villain—his very opinion in the letter! Abhorred villain, unnatural, detested, brutish villain—worse than brutish! Go, sirrah, seek him. I’ll apprehend him. Abominable villain! Where is he?

EDMOND I do not well know, my lord. If it shall please you to suspend your indignation against my brother till you can derive from him better testimony of his intent, you should run a certain course; where if you violently proceed against him, mistaking his purpose, it would make a great gap in your own honour and shake in pieces the heart of his obedience. I dare pawn down my life for him that he hath writ this to feel my affection to your honour, and to no other pretence of danger.

GLOUCESTER Think you so?

EDMOND If your honour judge it meet, I will place you where you shall hear us confer of this, and by an auricular assurance have your satisfaction, and that without any further delay than this very evening.

GLOUCESTER He cannot be such a monster. Edmond, seek him out, wind me into him, I pray you. Frame the business after your own wisdom. I would unstate myself to be in a due resolution.

EDMOND I will seek him, sir, presently, convey the business as I shall find means, and acquaint you withal.

GLOUCESTER These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us. Though the wisdom of nature can reason it thus and thus, yet nature finds itself scourged by the sequent effects. Love cools, friendship falls off, brothers divide; in cities, mutinies; in countries, discord; in palaces, treason; and the bond cracked ‘twixt son and father. This villain of mine comes under the prediction: there’s son against father. The King falls from bias of nature: there’s father against child. We have seen the best of our time. Machinations, hollowness, treachery, and all ruinous disorders follow us disquietly to our graves. Find out this villain, Edmond; it shall lose thee nothing. Do it carefully. And the noble and true-hearted Kent banished, his offence honesty! ’Tis strange.

Exit

EDMOND This is the excellent foppery of the world: that when we are sick in fortune—often the surfeits of our own behaviour—we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and stars, as if we were villains on necessity, fools by heavenly compulsion, knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance, drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of planetary influence, and all that we are evil in by a divine thrusting on. An admirable evasion of whore-master man, to lay his goatish disposition on the charge of a star! My father compounded with my mother under the Dragon’s tail and my nativity was under Ursa Major, so that it follows I am rough and lecherous. Fut! I should have been that I am had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing.

Enter Edgar

Pat he comes, like the catastrophe of the old comedy. My cue is villainous melancholy, with a sigh like Tom o’ Bedlam.

⌈He reads a book⌉

–O, these eclipses do portend these divisions. Fa, so, la, mi.

EDGAR How now, brother Edmond, what serious contemplation are you in?

EDMOND I am thinking, brother, of a prediction I read this other day, what should follow these eclipses.

EDGAR Do you busy yourself with that?

EDMOND I promise you, the effects he writes of succeed unhappily. When saw you my father last?

EDGAR The night gone by.

EDMOND Spake you with him?

EDGAR Ay, two hours together.

EDMOND Parted you in good terms? Found you no displeasure in him by word nor countenance?

EDGAR None at all.

EDMOND Bethink yourself wherein you may have offended him, and at my entreaty forbear his presence until some little time hath qualified the heat of his displeasure, which at this instant so rageth in him that with the mischief of your person it would scarcely allay.

EDGAR Some villain hath done me wrong.

EDMOND That’s my fear. I pray you have a continent forbearance till the speed of his rage goes slower; and, as I say, retire with me to my lodging, from whence I will fitly bring you to hear my lord speak. Pray ye, go. There’s my key. If you do stir abroad, go armed.

EDGAR Armed, brother?

EDMOND Brother, I advise you to the best. I am no honest man if there be any good meaning toward you. I have told you what I have seen and heard but faintly, nothing like the image and horror of it. Pray you, away.

EDGAR Shall I hear from you anon?

EDMOND I do serve you in this business.

Exit Edgar

A credulous father, and a brother noble,

Whose nature is so far from doing harms

That he suspects none; on whose foolish honesty

My practices ride easy. I see the business.

Let me, if not by birth, have lands by wit.

All with me’s meet that I can fashion fit.

Exit