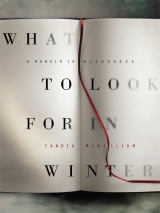

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Chapter 5: Mine Eyes Dazzle

After a first fit of the grand mal type, if that is what it was, a number of precautionary measures can be taken. They do not conventionally include a seaside trip to a newlywed shaman, but of those offered at a time when things had fallen apart, that seemed the most practical and effective. The consultant neurologist with whom an appointment had been made automatically by the hospital cancelled it on the day, even though by the time of this appointment, four months on, I had managed to be once more in that same hospital. But that’s to come, and hospital doctors are horribly stretched.

No one could work out why I had had a fit, so, or and, they stopped trying to. The consoling phrase used to me, as a layperson, by several doctors, was that I had ‘boiled over’ and that this is more common than one might suppose. I don’t doubt that. It’s a safe statement. There are a jolly good number of folk out there and you don’t want to go running away with the idea that you’re any different.

The only serious biochemical theory advanced for my fit was that I had given myself, in that careless way patients will, hyponatraemia. I mentioned this to a handsome wild boy who does much clubbing and who enjoys the attendant refreshments. Hyponatraemia is well known to him. It is the consequence of drinking an enormous quantity of water. Disco biscuits give you a thirst like a gravel pit. As a consequence of hyponatraemia, death is not unusual, the salts in the brain and blood having become drastically diluted.

I do drink a lot of water, but not that much. When I told the doctor who proffered this theory how much water I drink, I translated the imperial measures wrongly into metric, probably a mistake hardly any except the very oldest clubbers make, so I said litres for pints.

Like an alcohol counsellor, he doubled the number of units the client had actually offered as the amount imbibed and arrived at the conclusion that I drank eight litres of water daily. He had been seeing me almost fortnightly for a year and I had shown no symptoms of water damage before. Though I had put on several stones in weight, which might relate to some of the drugs, now that I mentioned it.

I wasn’t able any longer to walk around energetically as I had before I was blind, so I took account of that and ate carefully. I had fluctuated in size all my life but this fat felt doomy. It was solid and already old; it was hard like lamb fat. I could imagine it white and solid over the cold grey stew of my inner life. My limbs were no longer of any shape. They fell like sacks and settled oddly; sometimes I had to pull my legs across one another with my hands. I had been used to sitting with my longish legs crossed twice, at knee and ankle, for comfort.

I couldn’t sit in normal chairs without worrying that I might stand up with the chair stuck to my uncontrolledly voluminous arse. Yet at the start of 2008, when I went to my uncle Clem’s memorial service, before starting on all those high-dose prescription drugs, I had been able that morning to touch my forearms to the floor when I touched my toes, meet my hands behind across my back, and stretch so that my head lay on my calf when I sat on the floor with my legs in a V. I had had long slimmish legs and feet that I could fit into proper shoes. I had had flexible arms, not legs of mutton. I wanted to look nice for my surprisingly dead handsome uncle and his great-nephews and niece, my children.

Something was rebelling, now, only a few months on. I looked out of my body as does Winnie the buried woman from the pile of rubbish in Beckett’s Happy Days. My head came through, but even it was thicker, to look at.

I was not asking for the old ranginess in my fifties. I was just baffled by yet another thing gone quite so quick, another lost identifier. Fram is right to say that it is vain to mind the loss of what was never certainly mine in my appearance.

But the loss of usability, on a sudden, is a blow. I now had mass of a sort I felt unable to control, and was absurdly weak, for a woman who has lifted, carried and walked all her life. I was moving with the slow barging diffidence of a learner lorry driver who can’t yet work his mirrors. I knocked into people.

They did not always like it.

I got called names, or whistled at, ironically. I was twice asked in the street if I wanted a fuck. That makes you jump if you can’t see.

I avoided going out as much as I could.

On sunny days I saw less, after all, and I was ashamed of exposing even my clothed physical self.

I began to treat myself, as I have done periodically throughout my life, as the ugly person I had often felt like. I did it with practised dissociative skill.

I spared friend and stranger the sight of me.

I worried especially about this for my daughter. A pretty girl may not want a raging corker for a mother; but nor does she want a tired sow with lost eyes, who holds the wall when she feels her way along and appears to have shrunk from six feet down to five and a bit as she bends over her stick.

After the tentative suggestion of internal flooding after my fit, the judicious doctor wrote a prescription, which I took round the corner, paid several pedigree cats for, remembering that blepharospasm is a private matter medically (and drugs for its treatment therefore need a private prescription), and kept on obediently putting them into my mouth twenty-four times a day. I never less than liked this doctor. I never wasn’t interested by his method and levelness. I would say that I had perhaps wasted his time, to the tune of many cats. I have time too, though I have been conspicuously less good at selling it.

That August after the fit, Fram shook away the end of that academic year to tend his garden. Our son and I were at first in Edinburgh, at the Book Festival, fitting as many authors as we could into a day. It’s a pursuit that baffles me and makes me shy until I am in my son’s company when it feels just right. I suggest this is because he is an author born, whatever he chooses to do with it, and certainly he is a born reader, and to see with his ears or hear with his eyes has become one of my most reliable forms of escape from myself and the forms of thought that ambush me when the world’s sap sinks.

After Edinburgh, we went through to Glasgow and on to Oban, with a man named David from a local car firm. He heard our voices, kindly assumed it must be a first visit north and made a special stop to let us pet a Highland bullock, having explained to us that the haggis were all roosting indoors at this time of day.

Hamish the flamboyantly hairy orange bullock lived outside a teashop. He stood at the edge of his paddock, head over the fence, asking for sweeties. He had that look animals do have when every bit of them is fluffy. Just his wet rubbery nose and his pink tongue weren’t; and his strict galosh-like hooves. He was stroppy but inert and wanted something sugary before putting out. Under his long fringe, below his shaggy orange poncho, his forehead was fluffy, his shanks were fluffy. His orange pelt was backed by orange fluff, felted itself in orange fuzz. He glowed in his wet green paddock under the purple hill. How many hotels and provincial galleries hold paintings developed around that Scottish field of colour?

Hamish was apparently silly and actually indulgent, a creature-witness to the daftness of people, a sharer of the joke that it is to be shut up inside a body.

Like Ormiston my cat, who will lie on his back in his cat-suit of creamy fluff and display the centre parting through his foggy fur from chest to prettily lilac but now podded scrotum, and observe one with an expression that defies anyone to assert the dignity of their own embodiment, Hamish had the look of affront that goes with being of cuddly aspect.

Fram knew early in our time together that I was as much an animal familiar as a socialised person. I don’t mean that we related to one another through animal names like the disturbing couple from Look Back In Anger, but he recognised me at once for a companionate moth-eaten lion, with big paws twitching in its sleep, in the corner maybe of St Jerome’s study in a painting, or on a deserted gatepost in Scotland, tiredly rampant as though missing only the drinks tray or trolley from her front paws, or toothless but dancing and shaggily maned at a sooty stone fountain in Italy, moss clothing her where the water has for so long fallen. There are elements of St Jerome to Fram, the care for books, the asceticism, the poring close over text, the burned thinness as breakable as charcoal.

Part of being safe in love is being known and fully seen. The urge not to be known is superficial as well as primitive; facile and destructive compared with the need to be known, that increases as friends die and the world changes, that makes of the loved one an environment in which to root and come into leaf. The urge not fully to be known is the urge to recreate oneself and that is the urge to escape, as dangerous as a rip tide and as hard to harness or control. I lost worlds in their firm orbits when I left him, and now am trying to make on the wheel just a thin bowl to hold myself level within. I see this in the thaw, as I look at the true story of my life, which I thought I could leave resting under the chill light of a protective, eventually weighty, snow.

The mower is moving to and fro along the terraced levels of lawn at the back of the big house here on Colonsay. It has been too wet to mow for more than ten days but today the sun has been bright since six. Last night it was still light at ten and there is more than a month to go of lightening evenings and light nights.

After the fit but before the next failure of the body, I received a visit from a friend. Many friends we made when we were very young we would not make now. She and I are close but we leave views aside, or I prefer to. She does not so prefer, which is in itself a view. My own view has calmed, intensified, deepened since I have seen less. I’ve always been chary of views, in the plural. I think of them often as places in which to position yourself, to be seen to be positioned, places in which to stand still and get stiff not seeing very much and not thinking about what may be perfectly visible from the inward eye without so much fuss and noise and sending of highly opinionated postcards from the car park of the view.

My friend’s life has spun her compass in ways I am too sceptical, too off-put by solutions, to embrace. Of course, knowing me, she can read my tired eyeless if not toothless liony head when she lays out her brand-new views, that are working well enough for her.

She voiced an idea that is a common one but whose truth inheres, or so I think that I deeply believe, in its opposite, that she was glad I was doing a memoir as that is where truth lies, not in fiction.

Well, exactly so. It is in a memoir that truth will, if not lie, tell as many versions of itself as there are drops of water in a river. Does anyone who has lived feel that there is one version of their life? There is only the frozen water of story that will melt and retell itself in another shape, there are only the tides and storms, whose drift will be countered, whose wreckage will be rebuilt, in countless ways by the survivor, and the survivors of that survivor.

I was cross because I thought that she was doing two silly things. The first was attacking fiction and the second was losing out on all that fiction by an attachment to biography, as though felt life were confined to a recorded life. This attachment is fashionable. It is based on the idea that ‘life-writing’ is real, where fiction is not. That notion is perilously close to the idea that fiction is interesting only when we find ourselves in it, that identification is more essential than recognition and compassion and the acknowledgement of otherness. Not all biography is gossip, of course, but to assert that you prefer biography to fiction is not, as many now understand it to be, to reveal yourself as a person concerned only with what matters. It is to reveal yourself as a person who enjoys biography. (I’m one, emphatically, by the way.)

My friend will be looking for a trajectory in my memoir, a plot, a lesson learned, a message that can be extracted from the thousands of bottles.

She has as much chance of finding one as I have of returning to their stems the hundreds of cut daisies that lie now among the lines of clippings on the scented close-mown lawn under my window. Some of the clippings have been caught in the bin of the old mower, some have not. It’s over, it was grass, it will be compost, the flowers fall.

I can say nothing more to my friend with her firm view than that it was my life, that it sometimes went too slowly but was over too fast, now that I look back at it. It was all I had. The miracle would be to convey a breath of how it was.

Yesterday…now, yesterday is good and close, perhaps it may be tickled up to life, taken from the stream, and caught before its freckles and the blue shine on it go?

Yesterday was Sunday. It began bright at before six. Yet it did not decline into rain. It grew brighter all day, till by the evening the sea around the island was bright like polished blue metal, and the lochs inshore had the path of the sun across them, blazing.

Katie had promised her mother that we would go to look at the grave of the newly buried man, who had come all those years ago to collect seaweed to fertilise the fields, and who had stayed to live on the island.

The graveyard lies close by a ragged coast to the south-west of the island, away down from the school, where seven children are at present seniors, and two juniors. Katie met the juniors doing a project in the garden at the house, doing a project by the fruit cage. The project was, according to Seumas, who is three, ‘Counting strawberries’.

A skill it seems prudent to master as early as possible in life.

The man in the wilderness said to me,

How many strawberries grow in the sea?

I answered him as I thought good.

As many red herrings as grow in the wood.

The school on the island attains unbroken high standards. It is hard to think of a more concentrated or rich education for small children or of a school more ideally located or staffed to inspire application and initiative or develop native wit. These pupils are as surely made by their teacher, Carol, as are the tutees of an influential don. There has to be nothing she cannot do. This must literally be true, from the more conventional curriculum to the setting of a willow bower, playing the fiddle, telling otter pugs from cat’s paws, and sowing nine bean-rows. Three people from that school have recently graduated from Cambridge.

The closest mainland over that compass point out to sea beyond the rocks beyond the graveyard beyond the school is Canada. The graveyard at Kilchattan is exposed, but very green. The graves are set in two turfy yards, within dry-stone walls. A man came two years ago to repair these walls, and Katie and William and their older daughter, my god-daughter Flora, built a section of the wall under his guidance. He sees the compatibilities in the stones and sets them together so that together they will remain. Katie said that he did it as fast as a man laying out cards, and his stones lay immoveable in the places he had ordained for them, while her wall shoogled. Less, she said, though, than her husband William’s wall.

Because the day was bright and there was little wind, the small inland lochs were blue and bright over their brown as we drove to the graveyard, slowly. You must drive slowly. There are cows and their calves sitting across the road, and lambs taking a rest on knuckly legs, to feel the warmth of the asphalt through their fleece. The tar warms through quicker than the turf.

There are people out for a Sunday drive; there are churchgoers, and tourists. There is the shepherd, on her quad bike, and Angus, the special constable, in his crime-fighting vehicle.

Car accidents do happen, and the nearest hospital for a broken bone is either a ferry journey away, for which you may have to wait for two or more days, or a helicopter dash, with all the drama, expense and interruption that involves, calling the emergency people from the mainland and soothing and loading the stricken soul.

The graveyard is not at the church, which stands on the hill opposite the hotel and bar, looking down at the pier.

The graveyard is a pair of fields of marked places where human beings lie in earth. The stones number perhaps two and a half hundred. Katie and I read every one that afternoon unless the salty wind had worn it back to plain thin stone. The new grave was to our surprise covered with neatly placed flowers, none in cellophane or paper. Whether they had been tidied by a loving hand after the wind or whether the wind had spared them, I don’t know. I feel peculiar about reading the letters and notes that go with flowers for a grave as a rule, in case there be something sticky-beaked about the motive, but we did read until Katie found the flowers from her mum.

A proper measure was returned to friendship and familial ties at that grave. You cannot fret away the ties that exist in a place as small as this. Friendships cannot be consumed at whim or jettisoned as things move along. They must adapt to contiguity. This citiless place makes the true demands of civilisation.

We walked the graves, many of them crowned with the family name of the person below, MacNeill, McFadyen, McConnell, Titterton, McPhee, the beautiful strange surnames Buie and Blue. The Archibalds and Ians, the Hesters, Floras and Euphemias, the one Annabella, the many lost children, the two young men perished in accidents in the late nineteenth century, the gardener at the big house who worked here for fifty-eight years, are joined by many people now whom Katie and I remember, three handsome young men with whom we once danced, dead in their twenties and thirties, a heartbroken father, a man with a hole in his heart whom we hero-worshipped for his glamour and whose grave bears the name of his house and its aspect, ‘Seaview’. He was thirty-four when he died.

To one side lie the drowned, torpedoed in war, some from the MV Transylvania, one an Italian from an unknown vessel, ‘Morto Per La Patria’. There are able seamen, a donkeyman, a wife come alongside her husband decades on from his death alone at sea and his eventual rest in a place she may well not have known existed before he washed up drowned on its shore. Two young men were washed up just a day apart. Imagine the shock of those two days in 1946, the dreadful practicalities.

Fresh flowers lay on a couple of other graves than the new one, wooden crosses with a paper poppy on some of the servicemen’s graves, with their name and rank, or the bleak admission, ‘Known Unto God’.

It was sad but it was not false. We were walking among the dead, many of whom we could see in our heads. Some of the words on the graves we were stirred by, even those in the Gaelic we could not understand. The graveyard is not there for us, it is there for those who dwell in it. Or it may be there for us, when our time comes, that we cannot know. And then it will be there for our descendants or for those who miss us. The stones are temporary but longer lived than we are. The lovelier stones are to me those that fall more swiftly into decline, that are friendly to the kiss or clasp of lichen, that bloom into defacement.

Loneliest, it seems, monumental and unmodified, are the stones of Katie’s grandparents, her grandfather who carried those hard sacks to his melting jetty to nowhere, and his estranged wife. They lie together in the lee of a low wall, but as it were in single beds, each under one large stone like a lintel, with another granite stone on top. He died more than two decades before her.

I came to love her and she came to tolerate me, perhaps merely because I had graduated from being that ‘awful common girl who is always around’ to marrying the heir to an earldom. She was an indefatigable giver of recycled and mysterious presents with her name crossed out. She once gave Katie the hem of a kilt. She gave Quentin and me a history of the button, that had already been twice around the family tree. She painted and embroidered with a sense of colour that demonstrates her love of the island her spouse latterly forbade her by force of law to set foot upon. She was talented, rude, stylish, beastly and brave. I liked her, though perhaps it should be put on record that Papa, when asked how he could tell his mother and her identical twin apart, said, ‘Oh Aunt Va was the one who loved me.’ His mother covered surfaces all over this house with her painting, the laundry bathroom window with furling seaweed, the shutters with beavers, rhododendrons, shags, black-headed gulls. Her lively decorative spirit lives on in her handsome grandchildren; her dreadful trenchancy has entered my world of dead voices. When I took my firstborn to visit her, she told me that anything can happen if you let a workman near your freezer. They could for example take all your frozen herring roes. In which you will, naturally, have put your good jewels. I own neither freezer nor gems to place therein.

Oma’s grave is sad, and so is that of her husband, by many accounts a gentle interesting man. His bears his title. Hers bears her role, that of his wife, and his title. All else gone.

‘Known unto God’ tells as much as those two graves of any private self, though not to the biographer. The stories told upon the graves at Kilchattan are mostly poems. The sea that can look savage or ravenous beyond those graves was purring under the sun yesterday, creaming in repeatedly with its soothing repetitions close by all the recently undone of this place.

I have since leaving Fram feared that I will not be able to be with him after I die. Now I know that I cannot because it would no longer be right. I used to think it selfish that I wanted to go first, but now it is unselfish, because it tidies me up. Not only is this not his way of thinking, but he thinks it pointless and somewhat manipulative in me that it is mine. At last I will not only cease to be a worry, but I shall have a place to be, and a place where I am snug and quiet and feel nothing. There is something inconsiderate and clamorous in a person bleating unstoppingly for the other to whom all is referred. Get on, he says, stand up. I cannot be the person who is your shepherd, I least of all. You must tie another fleece to yourself and set out on the hill. You will not find a new mother, you may not find a mate, but you will do what innumerable women and men have done before you. You will carry on, as you are bound to do, the expedient fleece bound to you.

That is what truth to life is. The way to be true to life is to remain alive.

Later on Sunday, William took me to have a drink with our friend whose big window looks out over to Jura, whose raised beaches looked close enough to touch in the evening light across the blue sea. She has multiple sclerosis, is badly compromised physically, and frisky and busy mentally, running a bookshop, the community online newsletter, and belonging to many boards and committees. She told us about a recipe for cormorant pie; skart is the word in the Gaelic for cormorant and for shag, that the old harbourmaster, Big Peter, Para Mhor, used to enjoy in a pie. I remembered Peter, with his white sea-boots and his wide beard, his deep chest and his rosy cheeks. I had remembered him at his grave that morning. He held the old ferry in at the bow with a rope around a stanchion, balancing another rope sprung in tension at the stern. He slung sacks beneath the tyres of cars before they were wound out of the ferry by davits, when the ferry was not yet ro-ro (roll-on, roll-off). He wore petrol blue overalls that grew paler throughout the year and were replaced when they had reached a blue as thin as the last shallow sea over sand.

While we were taking a drink with our friend, a small red cruise ship came close to the island, and moored in the flat calm. Almost as soon as its anchor was set, the black ferry, twice its size, hauled through the silky water, with the large declaratory words Caledonian MacBrayne along the hull. For a moment it looked as though man had mastery over land and sea. We might have been looking, through our friend’s picture window, at a poster from the nineteen-sixties about advances in travel by sea. The scene might have been posed by models in a tank of moodless blue water, that same sea though that will ensure that not the drowned of this place alone are in time known only unto God.

On the way back from our drink, we drove into a sun so bright that it wasn’t just me who couldn’t see. William drove slowly by feel into the sun past stretches of water that pulled its white light down in stripes of glitter into themselves, wild flag iris leaves like knives at the lochans’ margins. At each passing-place we pulled in to let another car pass. We stopped for lambs. Why race to the end of a day so full of light?