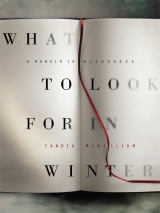

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Mealtime conversation was on the whole abstract or theoretical, whatever age you were. There was little people-talk unless it be of use, attached to a paper written, a law made, a proof offered. Avrion had made butter with Lorna’s breast milk, I seem to remember, and there was talk of self-made blood-pudding.

Two years ago, wandering around the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, I came face to face with Nou. There she was, miraculously at about my height, as never in life, dressed in blue, frowning, chin on hand, looking me straight in the eye. It was her portrait by Wyndham Lewis, which had been on the ping-pong room wall and under whose gaze, dancing this time to records of Scottish dance tunes, I fell in love for the first time with a grown human not resident in the ancient world. It is a love that came to nothing in the conventional sense so that it remains, for me at least, complete. Nor is it untried. The one who generated it absolutely without intent remains today a beloved friend and provided for years as it were an internal moral thermostat that I fell short of, but knew when I was doing so. It is not coincidental to my life as a novelist that he was a child in India and is a musical scientist. Nor is it coincidental to my private life.

Wyndham Lewis was a good choice to paint the young Nou. He got that density, that energy, that intellectual force. In the corner of the painting to the sitter’s right is a curious pair of antagonistic marks, written in paint, like scallops inverted, or fists opposed, conjunct yet fierce. If they encrypt Nou’s character, they do it well. The other attribute caught is her uncompromising seriousness, combined with an irresistibility, like that of some metal.

In the long-playing-record trunk in that library, there were also to be found the speeches of V. I. Lenin and a Russian phrase book from which I copied into my diary at that time ‘A rose is a flower. A man loves a woman. Death is inevitable.’ I also found a book on medieval Latin lyric by Helen Waddell and remember the words:

‘Vel confossus pariter

Morerer feliciter,’

that she translates as:

‘Low in the grave with thee

Happy to lie.’

I’ve used these words as soothers for years. They work as phrases whose meaning either dissolves, leaving you in a state of meditation, or tightens up, giving you plenty to think about.

I had discovered a great pleasure of the painful side of life: its relief, or exacerbation, by literature. Of course I’d been doing it all along but hadn’t realised.

It was typically bifocal of me to have lit upon the object of my distant love since his delightful brother was my first proper boyfriend. Between them, they constitute immortal disproof of the proposition that all Mitchisons are brilliant but not always super-subtle. Terence Mitchison was an undergraduate medieval historian at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, a place that was to recur and grow in my life. We met during the famous summer that Anthony Appiah, the grandson of Sir Stafford Cripps and nephew of the Queen of the Ashanti, said, and we were just thirteen, ‘It depends whether you have an eschatological Weltanschauung.’ The thing about Anthony was that he had some paisley flares and a blue rollneck and he could play the piano. The other thing was that we became best friends and that he’s never shown off in his life. He just was that far in front – like Prospero, but kinder.

Terence courted me with letters that would, if anyone knew where they were, constitute the most colourful archive you could wish for, literally. He breathed jokes, mainly of the verbal kind, and sent them to me colour-coded, brown for medieval jokes, green for rural jokes, pink for jokes to do with the history of Empire and so on. And, of course, puns resulted in multicoloured words. It was not that Terence was, as I am, a synaesthete whose synaesthesia is redundant or at any rate useless; he was an etymologist with a grip on detail. So considerable was this grip that when we took a holiday, later in our friendship, on a barge on the Brecon Beacon canal with schoolfriends, Terence had embroidered his Admiral’s cap with the barge’s name, Samuel Whiskers. Everything about Terence was thorough and good. He had embroidered another cap: HMS Leaky.

Which makes that swivel of disloyalty, or whatever it was, in me towards my idol, his older brother, extra mortifying, and I only hope Terence was well shot of his schoolgirl correspondent. At the start, I suspect that I fell, as through a trapdoor, for the blameless older brother for the simple, no doubt tediously biological, reason that he was, and remains, the single individual who has, since my mother and father, been able to carry me. His areas of specialism included blue-green algae and dreams. I used to read books about finite-dimensional vector space and Riemann surfaces to try to make myself appealing to this distinguished ludic individual. When he remarked, glancingly, that he thought blue more becoming than pink, I did as my mother would have and made a stew of woad, or rather Dylon dye, in Strong Navy and bunged all my clothes in. Nothing could have prepared this poor man for cause and its effect upon his silly child-friend.

I drooped around after him for pretty much a decade, during which his circle of friends, to some degree, took me up and conducted the kindest of intellectual experiments upon this peculiar child. So it was that I found myself building sandcastles (one, for example, of the Gesù in Rome) with the right-wing philosopher John Casey, being introduced to green Chartreuse by the composer Robin Holloway who later wrote me properly critical letters about my work, which he did not like; and becoming a friend for life of my idol’s lodger, with whom he would play piano duets, Roger Scruton, who was then a boy of twenty-seven with hair that flamed over a face that also burned white with seriousness. The architectural historian David Watkin taught me to dance the galope and asked me to marry him, which he must have forgotten, or at any rate I notice that we don’t seem to be married. They gave me books to read and were, I suppose, waiting to see what the result would be when I had ground my way through whatever it was: The Anatomy of Melancholy, Hadrian VII, The Quest for Corvo, all of Firbank, Memoirs of a Mathematician. Unknowing, I was a kind of Maisie. Their patience with me and tolerance of my mooncalf presence among them was admirable. I was a bit of a liver-enriched goose, I’m afraid. What kind of egg they expected me to lay I cannot imagine, but not this life that I am laying out now, I’m sure. I still possess the label of the 1955 Veuve Clicquot bottle that we shared, perhaps eight or ten of us, on my fifteenth birthday, over lunch. It is, with all my possessions, not to hand but in store, awaiting a return to a life unpacked.

Before these loves, though, came rupture and detachment from my father’s house in my early teens. He and I never exchanged words about it, but I left his home and did not come properly back to it again, and certainly not to live.

I had become compact of lies, a child of flies, a beelzebubbler, as my stepmother apprehended it, and she did not, quite understandably, want me near her children. I suspect too that I was growing to resemble my mother and that my father could not face another unhappy marriage; since the only thing that was wrong with his marriage to my stepmother was me, might there not be benefit for all concerned were I to be removed from the sum?

I had always fancied boarding school and now its allure was unequivocal. Several prospectuses were sent for. I liked the look of Cranborne Chase and Bedales. It turned out that my mother had left enough money for me to be sent away. I sat scholarships.

It was to Sherborne School for Girls in Dorset that I won a major scholarship. The adjustment from a school whose houses were called Argyll, Buccleuch, Douglas, Moray and Strathmore to an establishment for young ladies of England and the Commonwealth was actually not all that painful. The only sad thing was that I lost all trace of a Scottish accent, though my children tell me my voice changes as we cross the border north.

In the scholarship examination I had scored fewer than ten points out of a hundred for mathematics and these points given merely for the sake of face. A special division below all the others was created for me and for a girl who had been terribly damaged in a car accident. We were patiently taught by a Miss Hayward, who challenged us with such problems as: ‘You have a curtain rail that is four feet long. You have four curtain hooks. At what intervals do you place the curtain hooks?’

My housemistress was a Scot, Jean Stewart, and a place had been found for me under her care because a glamorous-sounding girl named Augusta had of a sudden decided to leave. I was no substitute for this Augusta. Huge, foreign, by now crop-haired, queerly named and in my old school uniform, I was an odd fish.

I learned to love my housemistress, who combined suffering with beauty and reticence. She was a devout Scots Presbyterian, later retiring to the Western Isles and becoming a minister, but I simply could not abide the diamantine, pearly, glorious heroine of a headmistress, the radiant Miss Reader-Harris, later Dame Diana Reader-Harris, who is revered beyond her death to this day. I have no doubt that she was good and that she had star quality of the regal, cinematic sort. She would have made a wonderful-looking wife for a dictator. I am almost certain that she, who wore a large, three-stoned diamond ring, had, poor woman, like so many of our other teachers, lost her fiancé in the war.

Etiquette demanded that we say goodnight to our housemistress with a curtsey and a handshake each night, also that we curtsey each time we encountered the headmistress in whatever circumstance we found ourselves. I was in the sanatorium with flu when the headmistress made a visit, and hopped out of bed to curtsey to her. She smouldered bluely. Her crown of white hair, her aura of lavender, her good tailoring, her well-manicured hands, her lovely face, all flinched. She knew satire when she saw it and she didn’t like it. She’d taken me on halfway through a term and I was absolutely not going to prove to be a disappointment after all the Christian kindness she had shown me.

So it was that I discovered institutionalised duplicity. That’s a harsh term for it, but how I got happily by at Sherborne was by succeeding academically and, within that cloak, doing whatever I wanted, so that when there was a putsch against smokers, I could say that I’d been smoking which was an expellable offence, but they didn’t want to get rid of me because, in their terms, I might be a success and go up to university, Somerville or Girton. It was understood that one would not apply to King’s College Cambridge, the only ‘mixed’ college at the time.

At first I didn’t have to work very hard at all because my Scottish school had been so far in advance of its English counterpart. This was bad for me and I hung about idly reading novels. We were permitted five items on our dressing table, including a picture of our parents. I haven’t owned one of those ever. There were dormitories divided into cubicles and a few rooms for sharing. Nothing at all about boarding school struck me as more disciplined, demanding or impinging than had been my recent experience of life at home. I’d have been happy to spend the holidays at school, and in some cases did spend half-holidays and other times with some poor teacher, mainly Mr Hartley who taught Scripture and referred to the Minor Prophets as ‘this Johnny Haggai’, and ‘that fellow Habakkuk’. We all longed for him to say ‘this Johnny Jesus’.

It didn’t strike me at the time that my departure to Sherborne might be the cause of any grief to my father and I have no idea whether or not it was. He sent the occasional elegant postcard with an architectural feature depicted on it, for example the star-pierced dome of the Royal Bank of Scotland in St Andrew Square. He was not a rich man and travel was expensive. He had a new family and I was very little fun for them to be around. On Sundays, we had to write to our parents. Very soon I started writing to other people’s parents instead of my own.

I had big feet with my full name written on the soles of my shoes. We were often at prayer, so when we knelt I could not avoid giggles from behind.

(Liv, who was once a chorister, has just told me, to my outrage on behalf of the bride, that she sang once at a wedding where the groom had taken the precaution before the service of writing on the bottom of his shoes: ‘HELP ME’.)

I’d only the sketchiest idea of how to make friends, as must by now be clear. Throughout my years at Sherborne, I was often ill and spent a disproportionate amount of time in the sanatorium being nursed by Sister Parrott and Nurse Greene, who in winter put goose fat on one’s nose against chapping.

On one such visit, I was in a sickroom with the eldest sister of a family from Scotland. She turned out to be the oldest of six. She was Jane Howard. Then came Katie who was apparently in my year, then Caroline, then Alexander, then Andrew and Emma, the twins. They lived on an island in the Hebrides. Its name was Colonsay.

Jane was a brave talker; during my cosy illness I listened spellbound to her stories of home and family. It was another kind of falling in love, and a kind I was used to. I was falling in love with a family. The parents, whose real names were Jinny and Euan, were known as Mummy and Papa (pronounced Puppa). The parents were young, busy, and alive. The mother wrote weekly letters to her daughters and sons. These letters were spicy with adventure and displayed a dashing tone that made of any material whatsoever an excellent story.

After some sniffing, because we were both used to sitting at the top of the class, Katie and I became the sort of inseparable that maddens adults. We remain so today, though were we to meet now at the age we are we might not care one bit for what we saw. She is practical, carries no fat and mistrusts display of or reference to emotion; she loves Hornblower, Patrick O’Brian, Nevil Shute, Alastair MacLean, The Lord of the Rings and Melville. I’ve read Moby-Dick only since I’ve been blind, and loved it. I am fond of HMS Ulysses and A Town Like Alice for love of Katie. We both dote on James Bond. She is a Bond girl type, too, and can quote pages of the sacred texts. I’m just asked to write forewords to them, that no thriller reader in his right mind would read.

Unlike Katie, I am not in practical terms resourceful, and am trying continually to put a name to emotion since I have discovered that apparently to suppress it makes you go blind. Katie is beautiful. Her father, whom soon I too was calling Papa, is partly Native American. His great-grandfather married a Cree. All the children, even blonde Emma, carry the stamp. Caro, who has married a Neapolitan and ‘become’ Italian, looks entirely Mediterranean till you look for what it is that makes her so. It’s the flashing teeth, the gesticulations, the mobility yet grandeur of feature, as though a pagan goddess spoke. She is taller than most Italians. So you see that several generations down, the consequences of this union with the Cree are apparent; perfect white teeth in wider mouths than human, almost lupine, intolerant eyebrows, flashing eyes, long bones, narrow pelvises, weirdly semaphoric flat-handed hand gestures, and a capacity to start bonfires with no materials but moss and flint.

For reasons that I don’t understand, fraternising between the school’s houses was not greatly encouraged; Jane, Katie and Caro were in a different house from me. I was in a house with a name I still only cautiously comprehend, Aldhelmsted East (it’s something to do with the ontological argument), which was over a bridge from the rest of the school. Katie and I were both passionate fans of a substance called junket, made with milk and rennet, an enzyme extracted from the stomach of calves. We made it in jam jars that we carried across the bridge in the pockets of our green tweed cloaks as gifts for one another. This is how our life has gone on to this day, carrying incomprehensible but to us amusing messages over whatever obstacle life has put in our way.

The dark star of the school was our friend Rosa Beddington, who was on her mother’s side a Wingfield-Digby. This family, who live at Sherborne Castle, had founded the school, so Rosa, in spite of her chain-smoking and early and dramatic effect upon men, became Head of School until she was demoted for being seen ‘drinking shorts in male company’. Rosa had grey hair when she was twelve and I was sitting behind her in Latin, which was one of the very few things she could not do, though she would have been able to had she decided that she approved of the subject. Like almost every femme fatale I have known, Rosa made no effort with men. She had a vocation and she fulfilled it. She became one of the very few female fellows of the Royal Society, shortly before she died aged forty-five, of cancer that had eaten every bit of her except her daily-fumigated lungs.

It is hard to know where to start with Rosa since it is a story of extreme compensation for absences. Her beautiful mother had been an Olympic equestrian and killed herself when Rosa was very young. Rosa lived with and was raised by devoted cousins who became mother and father to her. Her father, with whom she felt furious, came of a distinguished Anglo-Jewish family. Ada Leverson, Oscar Wilde’s Sphinx, was a distant relation. Her father was a competent painter and so was Rosa, who was also an observant draughtsman, which was one of the things that made her a unique microbiologist, since she could draw what she saw through the electron microscope and she saw more than had been seen before about the processes of cell development in embryos. Rosa’s father published several books, including a tribute to his Labrador, Pindar: a Dog to Remember.

I was with Rosa when she was told that the cancer that had been in her breast was now in her brain. We were in the old Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. Her husband Robin, who had already lost one wife to cancer, had rung me up and told me to go to Rosa right then. I got to her in time to hear a smartly dressed Australian lady doctor saying to Rosa, a young-looking woman with long silver hair, terrific curves and a moonstone on her hand,

‘You’re bright, so you must know it’s curtains.’

Rosa sent me out for two bottles of red and two packs of Dunhill. She lifted her booted legs on to the narrow hospital bed, crossed them at the elegant ankle, and lit up.

For the rest of her life, Rosa railed against the fact that because she had ‘Doctor’ before her name, other doctors presumed that she had no feelings. Not that she was railing on her own behalf, but on that of patients who weren’t even doctors; how did the doctors treat them?

In her dying months Rosa made a freehand and exact botanical tapestry that would cover a good-sized double bed. Every stitch was an act of will. Its ground is black, the most difficult of all colours in which to sew large areas. Yet not the tapestry but Rosa was being nightly unmade. She did tell me she was well in her dream-life but at the end she fought angrily with some apparition that made itself felt at her deathbed, perhaps her father, turning up at the last.

Rosa made a surprising schoolgirl because of her poise, deep voice, and innate aversion to wasting time. It’s pointless to speculate whether she knew she had to cram more into less time. She was a superb drinker. Hard spirits had no perceptible effect upon her; they certainly reinforced her already devastating effect on any man in her vicinity. She was drawn to much older men of powerful intellect. She is the only woman I know to whom a man has sent an entire antique ruby parure after only one meeting. Years later he shot himself, on Valentine’s Day. Rosa was fundamentally, and realistically, sad, which lent her a gunpowdery vivacity. Rosa also became attached to the Howards; large families have this fuzzy magnetic edge that pulls in others. The Howards deeply loved her. Her gap is shaped like that of a sibling in many lives. To and in her profession her gap is incalculable.

Rosa’s personality was in torsion, her character silver threaded with steel. Its quality was recognisable in her person, in her writing, in her work, and in the calibre of the men who loved her. Her widower, Robin Denniston, is more than twenty-five years her senior; it is cruel. Still he writes and still he reads and still he lacks her company.

At her end, it was not Katie or me whom Rosa and her body’s dying animal needed, but our other close schoolfriend, Emma, who has inherited from her own mother the gift of healing hands. She helped Rosa to peace and comfort by her presence and her touch as Rosa neared her death.

Emma’s mother wears a lipstick called Unshy Violet and is named Kiloran after a bay on the island of Colonsay. Emma is called Emma Kiloran. The name of the Laird who gets the girl in the Powell and Pressburger film I Know Where I’m Going is also Kiloran. In the film he is considerably less glamorous than Papa, who is first cousin to Emma’s mother. Emma’s mother remembers children’s parties given by Nancy Astor at Cliveden, where the children had a little parade of shops and went ‘shopping’ with their own paper bags. Over eighty, she can still touch her toes, is a corking dancer, and mother of six. My first term at Girton, Emma’s mother took me out to lunch with her own godmother, who was Kipling’s daughter, Elsie Bainbridge. She was wandering in her mind and I was no help, very likely wandering in my own. Kiloran held things together. It is what she does.

She has never married again since the children’s father shot himself late one summer. Lucy, the youngest child, was still tiny.

That day, we were all, Rosa, Katie and I, going to Emma’s home on the farm in Dorset for lunch, a swim, a glimpse at the news papers and to visit the local steam fair, which had become an annual treat. Emma’s mother was the first person I knew who peeled cooked broad beans so that the little vegetable was bright green and digestible. She served them with thick home-made mayonnaise. On that day, we did still go to the farm for lunch.

Emma’s mother fed us, sat with us, looked after her still young children. A widow for under a day, she gave time to all these things.

Where does pain go?

Emma’s father was a joy to get a laugh out of. His was a languid slim English beauty. He loved jazz and secret jokes. I only once really got a laugh from him and it was when he came down to the disintegrating tennis court on Colonsay and saw something he thought he would never see in his life, which was me playing tennis. His daughter, my friend Emma, who is half my size and vitally bossy, had the same reaction when she saw me driving. We were going along a perfectly ordinary road and over a perfectly ordinary bridge.

‘Claude, darling, can you get out now and let me take over?’ she said, and completed the movement, exactly in the manner of her elegant father relieving me of the implausible tennis racquet when I was thirteen on the tennis court by the lupin field, where the tall pink and lilac flowers grew like a crop. Made into patties with water and cooked on hot stones, the flour made from ground lupin-seeds may have composed part of the diet of ancient man. Just think of the labour in collecting the stripped piplings, like lentils, their silky podlets discarded into frilly heaps.

As the slaps of my own familial tide broke repeatedly upon me, it seemed that the choice was to stay and be damaging or to slip away.

I did not run away from home. I took a boat.

I don’t know whether it was natural buoyant pessimism, self-paining good manners, a slight aversion to his oldest child, or simple exhaustion that led my father to take my disaffection with such quietness. He was a man not without anger, but the complications that came with keeping me at the heart of the home were painful and distasteful. Since his consciousness was of a piece with his tentative but utterly confident draughtsmanship, it is perfectly possible that he decided without even consulting himself to leave the area in his life that was concerned with me with rather more outline than shading. Unlike me, my father was absolutely not a monster of self-control. His life made intolerable demands upon him and he bore them apparently easily as though born to the task. I wish we had spoken more together. At the time, if we chatted, so attuned was our language that it seemed somehow discourteous to my stepmother whose English is perfect, but not highly nuanced. The responsibility for the jagged edge left by my departure was all mine and I only hope it healed as swiftly as it seemed to. Both my father and I had been so trained to be retiring that I have no idea whether he was as I felt myself to be, when I dared to think about it, haemorrhaging in my own nature internally, having somehow betrayed both parents, a stepmother and her children, by the time I was fifteen.

The internal valve used to decompress such feelings is commonly some means of escape or oblivion; I took one and was to take the other.

Today, in blind-time, it is the Wednesday of the Chelsea Flower Show. Staying in the flat last night was my landlord’s mother, a gardener by profession. Since she was coming to her own son’s house she need have brought no gift, but she had chosen for me Ted Hughes’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I hadn’t read it since 1997, and was at once excited to see the russet cover. But that was all I could see. Somehow it seemed a perfect present and I remembered how struck I had been by Hughes’s translation of the story of Daphne; in my recall, the bloody words sprang leaved with green.

As if by telepathy, my landlord, who had accompanied his mother, asked, ‘Have you read Christopher Logue’s Homer?’

‘I love it. All Day Permanent Red,’ I replied. The luxury, for even two sentences, of an exchange about reading, after these dry months, was delicious.

It became plain to me only two days ago that we are in the season of sweet peas and peonies. One of my doctors lives within creeping distance and I feel a sense of achievement if I can get there and back without falling over or crashing into someone. Chelsea Week, I thought to myself, with plenty of nice country people up in town, would be a good time to make this stab at normality. It began as a treat. The King’s Road was the usual troubling sequence of negotiations and feints. Then there’s the big island to be gained in Sloane Square. Once in Sloane Street, I was sure I’d start to smell floral displays set out by the shops to attract the pollen-gatherers up for the Flower Show. I passed two neoclassical tubs of sweet flowery spikes, missed a lady who I could tell was very smart from her heels and her smell and from her polite, ‘I’m so sorry’, wobbled on for a bit more and bashed into someone around my height, gender female, coat weatherproof, accent cut-glass, shock utter, who shouted, ‘You fucking bitch.’

Perhaps she had just come from the doctor where she had heard bad news, or maybe the parking had been impossible or the train up from the country running late. Who is to say that none of us might not have said it?

There are some doctors who are in themselves curative. They lower your anxiety and your pulse as they speak; you sense their truth. This doctor is one such and I left his surgery capable even of seeing my way down the front steps. I walked home remade to a degree by this insightful man. It was only in my own street that I noticed my skirt had fallen down and that I was shuffling along inside a puddle of grey jersey that it had made around my shoes. The white stick was handy at pulling it up and re-establishing it. Another benefit of not seeing is that I didn’t see if anyone saw.

I am for the moment perching in this flat like a gull on a cliff. The metaphor isn’t overstretched. I am a bit of a gull, being blind, and gullible at the best of times. The flat might certainly in one way be likened to a cliff, for it is enormously tall. My friend and landlord has tucked me in under his wing in what was once one of the Tite Street studios of John Singer Sargent. Liv and I work in his studio, whose windows face north and south, twenty feet of sheer light, with muslin soothing or baffling the light over the street-side window.

It is not possible to be in this room and not feel better. It is exhilarating and it feels full of the ghosts of work. At present, it is not decorated, save accidentally and provisionally. Dressed or undressed, done-up or bare-boned, it is a room that in itself provides breath. I don’t believe in inspiration of the kind you wait around for, but this room has breathed some life back into me.

Sometimes in the night, between about 4 and 5 a.m., I can see a bit to read. I took down a book by Michael Levey called The Soul of the Eye. It’s an anthology about painters and painting; mostly it consists of painters themselves talking about painting and drawing.

I fell on two things, and now it is the day it is very painful, literally, to read them, but here they are, first Sargent himself in a letter of 1901: ‘The conventionalities of portrait painting are only tolerable in one who is a good painter—if he is only a good portrait painter he is nobody. Try to become a painter first and then apply your knowledge to a special branch – but do not begin by learning what is required for a special branch or you will become a mannerist.’

In the pale gap of reading time that I was granted I came too upon this, from On Modern Art by Paul Klee (1924): ‘Had I wished to present the man “as he is”, then I should have had to use such bewildering confusion of line that pure elementary representation would have been out of the question. The result would have been vagueness beyond recognition.’