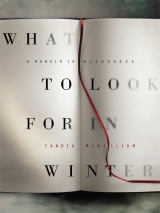

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

There is a particular formal stance of heartlessness that is a certain English way of protecting the heart, the elegant sternness that is one mode and often goes with the throwaway unadvertised, indeed denied, deep sensibility that sees off the vain and fake. It may be found at a peak of comedy and sadness in the work of Evelyn Waugh. It has been a tone congenial to Fram all along and now he inhabits it.

He is an alert reader. He grasped just as well too the empty dove-cote that is the McWilliam tone. Scots say doocot, and so do I, but I thought I should spell it out. It’s only by a feather that I didn’t say columbarium, which is the word that first came to me; but that word is too full and successful and plump, though hardly too classical, for my father, who mentions in one of his books the fine columbarium kept by Drummond of Hawthornden.

I left Hampshire just in time to return there for our customary family Christmas.

I travelled by train from London carrying nothing but the stockings for the younger children. Standing room only on the train.

‘You are joking?’ said the woman who stood bumpily next to me in the vestibule when I told her I couldn’t see very well, which was why I was peering around and craning, ‘I had you down for different, but not blind. You’ve got lipstick on.’

We talked about Christmas plans.

Her son-in-law made sure the family had a tree that wasn’t just thrown away. They had one tree outdoors with lights and real roots in the ground, and an artificial tree indoors with a long string of bud lights that also came in useful at birthdays. This was the first year she wasn’t taking her cat, Graham, to the family over Christmas. The neighbour had a key and was going into her flat on the day itself, with Graham’s stocking.

‘Nothing fancy, though. Toys, biscuits, a card and that. Just what he’d expect.’

Chapter 7: Snowdropped In

On 8 January, my cat Ormiston was run over, the first time ever he had strayed from the girls’ garden, where all summer he chewed grass and flew up to pat the air inaccurately over the spread purple buddleia tassels where a butterfly had been. Killed instantly, no marks. I still don’t think about it. I skirt it in my mind because I am afraid to start, and, if he was only a cat, what do I do with all the other grief? Crying helps the sight after all.

Or it did, before I had the first operation for the Crawford Brow Suspension, on the 21st of January of this year, 2009. My eyes are different since that operation. Crying is hotter and tighter. I’ll come to that.

Leander and Rachel were wretched. They had a haunted sense that if he had stayed with me he would have been alive. If he’d stayed with me, though, he wouldn’t have had such a life, with companions, butterfly-attracting plants put in at his request, and fresh fish. He would not have had his summer of being Warburton and exploring the uncatty group ethic he enjoyed. He was a team player; an unusual characteristic in a cat.

After Ormy was buried, Minoo went round to the house in Oxford. He prefers his cats disdainful, sardonic and free, but he ate an entire lemon drizzle cake in memory of Ormy and reported the handsome location of my people-pleasing cat’s remains.

Something of Ormy’s appeal for me was that slight dogginess. He was in on the joke and played up to it, sometimes allowing himself to retrieve a ball if we were alone and unobserved.

He was funny, and you laugh aloud less often if you live on your own and don’t really read. I didn’t think I would ever say that about myself. It’s always been a sentence that puzzled me: ‘I don’t really read.’ I see it now. It means, ‘I read what I have to, like instructions on dangerous machinery or in lifts.’

My first blind summer, two friends, married to one another, had sat with me at Tite Street. They’d brought a rhubarb tart with crème patissière. He had glancingly said that he had counselled a mutual friend not to buy a puppy as it would be just another thing to grow fond of and eventually to lose. Rita the blue cat had fallen in love with him.

Now, a year and a half on, he, I and Rita remained above the earth. Ormiston had been an inch of air, a pinch of fluff. My friend’s wife had been his response and crown of life. Who can plumb her loss? Nothing took her away. Nothing had her. Nothing had its victory. Nothing endures.

I now missed the foolish flat face of my cat up against my neck, telling me that it was time to get up at five-thirty in the morning. Even though he had been doing it in another house, with other people, I had known he was on earth and cared for. What comic strands have emerged throughout these years of eye-time (well? There is much talk of me-time). Ormy had been a guileless occasion of laughter.

Others went some way to providing other forms of diversion. Some have to be buried for discretion, or transmuted.

My favourite fun theme has been the silent wager I make with myself about the literary ambitions of the medically distinguished, and of quacks, too, now that I think about it.

It’s my limited understanding that I have been visiting doctors so regularly for thirty-six months because I am decreasingly able to see. With my eyes, that is. My, admittedly subjective, sense has been that reading, by which I not only made to some extent my living, and by which I live, has become difficult. I’ll put it simply. Very often I can’t see. I’m blind.

You will be aware of this. You are a reader.

However, not invariably, but often enough to give reality a firm shake, a doctor will say to me as I leave his consulting rooms, very possibly having written a cheque (is that where I go wrong? They see that I can write, after all?), ‘Ah, Mrs Dinshaw, Candia, did you say you were a writer? Books, is that?’

A bit. Once. Things a bit challenging at present. My eyes, you see. Cranking the odd thing out for friends. Scottish literary papers. Things like that (thinking, ‘That’ll put him off. Surely he will realise that it’s a polite rebuttal of what he doesn’t know I know he’s going to say?’)

Women practitioners are as liable to do this as men. Let me be fair.

‘Ah yes. I must ask my wife to look you up. I don’t get much time to read. Other than for work. Papers, you know.’

Indeed so.

‘But you meet all sorts doing this job. It’s taken me all over the world. Some pretty amazing places. You wouldn’t believe. And I’ve often thought.’

If you had the time.

‘If I had a moment, that it would make a book. An interesting one.’

Not a novel, then.

‘I often think that real life reaches places, well, you won’t mind my saying this, but truth is, it’s not just a cliché, stranger than fiction. And you don’t make anything up. It’s all true.’

This is getting in deep. Ask it, do.

‘Would you know of who I should talk to about getting it published?’

And then, a little carried away by the different glories attendant upon the idea of being a writer as well as a doctor, ‘Would you mind having a look at it for me? I’ve actually had time to get something down. It’s typed, you know. No doctor’s writing!’

I am really interested by doctors. I wanted to be one. My mother and I, retrospect tells me, both go, or went, for tall men in old-fashioned clothes and good overcoats, which was, in Edinburgh terms in her young womanhood, doctors. We visited a doctor with pinstriped long legs and a watch chain quite a lot. I sat on his knee and he gave me boiled sweets from a jar with no top. His height and expertise and silver hair imprinted me for life with one way of being a glamorous man. I’ve no idea who prescribed her sleepers.

I would happily write about doctors in fiction. Or write fiction about doctors, or help a doctor friend write a paper. I might easily ghost a doctor’s memoir, should he want me to, were he to find my sight. A fair swap, words for seeing?

I except from all this my GP, whose understanding, he has self-deprecatingly said to me, falls short of words. It doesn’t. It goes beneath them and into music. His kind of doctoring has that human affinity that used to be called compassion.

As well as the doctor-autobiographers to whom I felt I couldn’t at that time give the assistance required, there was new and much more interesting comedy in the form of the surgeon who has come to the salvation of blepharospastics with his two-part operation. When people keep saying to you, ‘Of course, he is brilliant’, you know that you are going to be handed a sharp spray of human traits.

His name is Alexander Foss. I heard of him because a fellow sufferer from blepharospasm, Marion Bailey, had written to me after reading a piece that The Times reprinted from The Scottish Review of Books that I wrote about being blind and not blind. She and her husband have become as godparents to my eyes; they are the chief kind strangers in our family’s recent history. Alexander Foss gave Marion back her sight. She understands exactly the trap and paradox of the maddening condition that is blepharospasm. Her courage and generosity have kept me upright. She wrote to me, enclosing photographs, about the operations with which Alexander Foss had given her back her sight.

John and Marion Bailey came to meet Olly and me. Her story was my own, baffling, alarming, frustrating, frightening, intractable. But she had found some kind of redress, and now, if she husbanded it attentively, had a good measure of sight. We decided to follow her generous example. Words, their publication, and their being read, passed sight through the hands of Alexander Foss from Marion Bailey’s eyes to my own. How can I thank them all enough?

Annabel and I had made an appointment to meet Mr Foss in the Midlands, where he practises, before Christmas. We drove up in December snow, late one Monday. Our treat was a boutique hotel in Nottingham. I had a disabled room with a red cord to tug in case of falling. I was in a pneumatic boot by this time, and as ever used my white stick, not to feel my way, but to tell people not to be upset if I crashed into things, and that I was best avoided. The plumbing and electricity in the hotel were of that unexplained hidden kind that only those born to mobile phones can operate without fiddling and splash. The comfort was practical, the welcome warm.

Mr Foss works within swifter time passages than the rest of the race. His supreme charm as a doctor is that he does no prologue, no soothing, no explanation, no awful chat. I could tell at once that he was a surgeon, tout court, pure brain and action. We arrived, we asked questions from our careful list, then we were out. We tried in the coming weeks to work out what this acute man had said. We had fun thinking of things that he would be least likely to say. These included:

How was your journey?

Are you staying locally?

And the family, how are they taking it?

Christmas plans, at all?

What a relief it was. Does the mutton roast want to be asked about its native pastures by the man with the whetstone and the blade?

We took against him for about two minutes each and then without knowing it we turned him into a hero. I suppose he had been auditioning us too. Luckily Annabel is a doctor’s daughter and managed a direct question.

Would it hurt for a long time afterwards?

I, sitting down, am about up to his chest when he is standing. He is nonetheless a formidable presence. His words come out at the speed of a lizard’s tongue, where the fly is your attention. Only much later do you realise what’s happened or been said. He smiles when he says the worst things, but not unkindly, at all. More like a true wit. I think he may be one. My guess is that he will not linger because what he does is of such intense moment. You can with ease imagine him seeing off death, around which he is often, as he is around the dark of blindness. His specialism is cancer of the eyes. He clicks and pops like an indoor firework.

What he told us was that I had one of the two worst cases of blepharospasm he had seen, and that I was lucky, as twenty years ago I would’ve been sectioned, that if I disliked him now I would hate him after the first operation, after the second it would be curtains for us, it would hurt so much.

Annabel and I returned south through the snow with a new person to develop inside the story. We each kept remembering delightfully, in a slow conventional world, rude, actually terrific, things he had said.

We started inventing them.

That leg’ll have to come off too; no point holding on to a duff limb.

Prepare yourself for complete failure; no operation is more than a good try.

Only one thing’s ever certain.

We imagined him paying compliments:

That hat has got to come off.

Ordering a meal:

Where’s the bill?

Proposing:

It’s shortly our tenth anniversary.

We liked Mr Foss.

For my first operation, it was again Annabel who took me. We tried to imagine, in hospital that January morning before I went down to the theatre, what he might say when he came on his visit to me before I was knocked out and wheeled in for his attention.

Mr Foss came into the clean little hospital room where I was too big for everything, chairs, bed, gown, slippers, paper knickers.

He had a form.

We’d been surmising and practising reassuringly feel-bad things he might be moved, or, admit it, induced, to say.

Annabel was in the lead with, ‘I’m dispensing with time-wasting anaesthesia.’

She had also scored highly with, ‘Look here, I’m busy today.’

He raced through the form. It was the usual. Next of kin, religion, etc.

He filled in the name of the operation: Crawford Brow Suspension.

Then he spluttered boyishly, ‘Benefits of operation?’

We waited. It was, after all, his field.

‘None. No benefits. None at all. Not that I can honestly say,’ he said, and was gone, leaving us in the highest possible spirits. That man could be a general. One would lose a limb for him with his surgical high spirits.

There used to be a phrase, used of certain drinks, ‘A meal in itself’.

Mr Foss is the life force in itself.

This is not in my experience true of most doctors.

Annabel set off for the South; she drives with mettle. She is the sort of ladylike quiet person with quick reactions whom you will find calmly running things when flashier ones have decamped. Accomplished, brave, capable, dutiful, her alphabet might begin. She can name most popular music tracks of the last forty years, and keep a poker face.

It’s odd. I am afraid of blue eyes, yet both Annabel and Claudia have them, markedly so, each in her way. Annabel’s are pale blue, really like aquamarines, and give you a shiver with their bright chill and almost pure colour, no black but for a pierced dot. If she weren’t smiling below them, they would be icy, and can look uninhabited. Claudia’s too can alarm because they inhabit a face that will not play along with anything that discomfits.

Both Annabel and Claudia have a gaze of pinning intentness. Each is a contact-lens wearer of long standing, and short-sighted. Both shake themselves when their eyes are tired, as though to refocus. Each pushes her fringe up with a hand to catch and ingest light through her pair of blue irises.

My own pair of green eyes woke up in the afternoon that January with bloody blinkers made of gauze strapped over them. My whole face, when I patted it, was strapped, like a mummy in a horror film.

I was ridiculously anxious that no nurse should think that I had had a cosmetic procedure. I knew these were going on around me in that hospital.

When I came round in the post-operative room, a nice young male anaesthetist asked, ‘Are you married?’

I replied that I was but that as I understood it, it was complicated and the terms hadn’t been invented yet and that my husband lived with someone else whom I was fond of.

I thought that this was a good opportunity to start as I meant to go on, naming things as I awoke into this new post-operative world.

Poor young man. He probably wanted only to see if I was sufficiently unwoozy to recall elementary facts, like the name of the Prime Minister. He got an essay. I don’t even know how to fill in forms. I alternate between ‘Married’ and ‘Separated’. I think I want to put what our son wants me to put. I must ask him.

I asked the young man his own marital status. He had a wife, he said, from Edinburgh, actually, away at the moment with his brother’s wife, also from that city, also a nurse. You couldn’t keep those Edinburgh girls away from home, he said. At least he supposed they were going home because they were homesick and it was nothing worse.

He spoke with healthy confidence.

‘I’m getting so I miss the place too, actually,’ he said, and patted me in an encouraging way. ‘You should go there one time when your eyes are better. It’s gorgeous.’

Later in that day with my stitched eyes behind their blinkers, there was another conversation that pushed plausibility to its limits.

As far as I could tell, it was evening. A woman’s voice, South African, almost social in its willingness to interact, reached me, enquiring about various practical matters. I replied.

I had had supper, insofar as I wanted it. I had found the toilet. Yes, I was used to finding my way by feel around the place, it was one of the upsides of not having been able to see that much before. Might I have a sleeping pill?

I might indeed not have a sleeping pill. I had just had a general anaesthetic. Did I know the inadvisability of risking it?

Silly me. I’m sorry.

Do you usually have sleeping pills? Are you aware of the dangers of dependency on prescription drugs?

Yup, I bullyingly said from inside my bandages, I’m a twelve-stepped alcoholic committed to rooting out addiction wherever I encounter it day and night.

How many years’ sobriety?

Oh God, she had the lingo. Medical people on the whole absolutely do not speak AA talk, unless they are ‘in the Fellowship’.

Oh, what had I done? Were we going to swap drunkalogues, as they are chattily known, deep into the hospital night?

But it didn’t go that way.

I said, modestly, or rudely, ‘A few’, which is a sort of signal to be released that only the sensitive take in. It means, ‘I haven’t had a drink for quite a long time. Years, probably nearer ten than five.’

It is a way of not making newly sober people, who may have achieved those first, literally miraculous, few un-drunk days, feel small. It is a way of not bullying.

Her next question quite baffled me. ‘Are you privatised?’ she asked.

I thought I could hear earrings. So, not a nurse, if allowed to wear tinkly jewellery at work.

‘I’m paying for this procedure. Do you mean that?’

‘No’, she replied, ‘I meant, are you married?’

I had never heard the expression.

I told her what I had told the nice young man with the wife from Edinburgh. Life was offering me exactly what was required, an opportunity to be plain and clear about what remained obscure – at any rate in words – to me.

‘Well, if you were a writer, you could write about it,’ she said.

I couldn’t engage with that. I was barely sure any more that I was anything, let alone a writer. I did the interviewee trick, and turned the tables.

‘Are you privatised?’ I asked. I wish now that I’d asked her where this odd term comes from. Can it make the husband feel nice, this microeconomic form of expression?

‘I,’ she announced, ‘am very happily privatised.’

She too has a terrific name. I will call her Theophania Droptangler.

The spirit of the woman, whose bright clothes I could hear and whose warmth was toasting me merrily through the anaesthetic and bandages and darkness, suggested there might be something well worth chasing on to the page. The next morning she was the first to come to me, at the sort of time my cat might have begun the day.

She was more than a chatty woman used to talking to zombies. In the intervals of her night watch, she had done a lot of background research.

‘So you weren’t bullshitting,’ she said. ‘You had it right you’re a writer.’

I said, ‘What?’

‘I found you. It was that unusual first name. We’re sitting ducks for stalkers, darling. And I’ve decided you can have seven sleepers to take away because I trust you.’

Useful being called Candia if it procures you sleep medication and binds you to other people with funny names.

I asked the nurses what this earring-loud lady looked like. I wanted to see if it matched my picture. She had told me her age, which was more than sixty. They confirmed all of it, sunshine colours usually reds, pinks, turquoise, lovely dark skin they said, henna through her hair, tiny like a bird, lots of kids, must be around fifty, looks about forty, and earrings like you would not find in a shop. Earrings in the shape of things, parrots on perches, ice creams in soda glasses with two straws, cactuses.

‘She’s exotic. Not like a doctor, more like a writer.’

The next stretch of time was like no other in my life. The closest I have come to it is V.S. Naipaul’s Enigma of Arrival, a book I have loved more on each rereading.

As I recall the book, it is an account of the writer’s time at a small house on an estate that had belonged to the Tennants, part of the set that included Ettie Desborough and the family who had lived at Clouds House, known to me for its architecture, its inhabitants the Souls, and its efficacy at drying me out. The estate was in fact Wilsford, to whose melancholy sale of contents Fram and I had been just after the death of its owner, Stephen Tennant, the lover of Siegfried Sassoon and later recluse, who dwelt alone indoors making bulgy drawings of matelots in many colours of biro, seldom leaving his bed and wearing powder and lipstick, in rooms upon which were drawn white satin curtains full of dust and in which vases of white ostrich plumes fussed up into the heavy air. Those impressions were gained from the sale and the house’s interior, the sad boxes of stuff that were having a harsh time of it in daylight, props as they were for a life of delectable tackiness and gimcrack fun, all, no doubt, in revolt against the stout Lowland virtues of solidity, bleach and no jokes, against which Tennants, beneficiaries of a chemical fortune, have for the last few generations so incandescently, sometimes chemically, rebelled.

The Enigma of Arrival, as I remember it, a recall of reading through blindness and forgetting, which seems in itself the sort of distancing such a monument to passing might rather enjoy having inspired, grows like moss upon the rapt reader, who perfectly enters its mood and is made part of it as he proceeds. Naipaul conveys the oldness of the landscape and the paths worn upon it, the ingrownness of the community and the dreams that make us who we are and what we might have hoped to have been. It is about hope and disappointment, dreams and death, and how worlds meet. It shows the absorptive power of the famously self-defining Naipaul. It is a great book. I can envisage its being read for many years beyond the time of our grandchildren because it is apparently clear yet it takes you into itself and shows you things there in the dimness for which you did not have words. It offers an England that isn’t ‘literary’. It’s geographical and spiritual. With words, it goes beyond words. Just as the artist is rare who can write drunkenness, the artist is rare who can describe our pre-verbal sensations and thoughts.

Not far from the hospital where my eyes were first cut, about forty minutes away maybe, stands an enormous house with a stony name, in woods famed for their many snowdrops.

What follows is not to do with the actual lineaments of anything that happened. My eyes could not see, I could barely walk, I was alone for long periods. The spring of 2009 was held in the grip of the most sudden and extreme snowfall in Britain since 1964.

The prevailing colour of my time up there is a white that fluctuates between being the blurry edges of my stitched-up eyes, with long filaments or tresses of light, the white of the snow-laden sky pressing down on the snow-covered earth, the fallen white of snowdrops beginning over one weekend to make shivery pools under black trees, the white stillness of the frozen lake, and the long white bath which I could not make hot, mainly because I was too passive to mention that the water ran at a heat that met the cold air without steaming. The big house was beyond the garden of the large Georgian vicarage that I had rented in a fantasy of recuperative entertaining and a mistaken certainty that I needed to be near the hospital. I believe that I was in this commodious house for six weeks. It was not unusual in me that I felt like an interloper. This was made worse because I was bed-bound, so couldn’t fall into my usual pattern of cooking and cleaning in order to feel less guilty. I had to lie still. I couldn’t afford this sojourn in any sense.

My eyes were prickly with big stitches of black thread holding them together. I was told the thread would melt and it did. My face was all bruise which became it rather if you forgot that it had been a face. It looked like those potatoes that are blue all through with a thin skin.

I had brought with me a Dictaphone, with an idea of dictating a novel into twenty-four one-hour-long tapes as small as eyeshadow pans. At first, I ignored it and then I realised that I must make a routine or I would…I don’t know what.

And that’s it. I don’t know why it was as it was. I felt as though I had fallen through time and into the lives of other people who did not know me. I felt as though I were being kept on ice to be unfrozen and eaten later.

I was melting through the money my house had fetched.

The vicarage had seen unhappiness, perhaps, but what house has not? I had no telephone reception, but that is not unusual in my life. I have quite little here on Colonsay.

I was clean, warm, and cared for with more than kindness by a man of unimpeachable cooking and organisational skills, with elegant grooming and a perfect memory for tractor models and railway time-tables. These last composed much of our conversation as he took me through the snowbound village, re-teaching me how to walk with the patience of a mother. He had worked on the railways and then his smouldering good looks had brought him to the attention of the local squire, and a golden age of triangular emotional tolerance had commenced in the stone pile by the lake, a golden age that had come to a close only with the passing of the squire, lamented, celebrated and beloved right through from Eton, where he had Wilfred Thesiger as his fagmaster, the Army, the war, and the long reign as squire, with his fond family and attachments around him up to his fairly recent death, which was crowned with posthumous literary plaudits and rich memory.

I was twice as cut off by the snow re-bandaging the world as I was by my not-seeing eyes. The world seemed to be slipping, as though I were carrying sheets of sharp but melting ice and trying to slot them into sash windows. Nothing was solid, nothing stayed in its place, only the white felt firm. The safest place to be was in the bath under water or in bed under sheets.

I will not forget the silent arrival of my hot-water bottles, each covered like a piglet in a coat, carried by my handsome carer as he padded in three times a day with them. Their heat was my emotional life.

For the last ten days, I kept up a sort of routine, which involved spending the day in the part of the house that had once been its nursery, and spoke words into my Dictaphone. I did twenty hours. It wasn’t as shapely as a novel, it was far too deep in snow, and I was able to see, when my last stitch had melted and my swollen drifts of cheek settled back down, that not one of the tiny cassettes had failed to snarl up on itself with the discretion of a wormcast in sand. So much for my novel written in snow.

I learned later that friends of mine had decorated the house, friends who had decorated the house in which Quentin and I had lived when our daughter was born. Perhaps that simple graphic explanation was a key to the locked sense of being doubly not present, of being a ghost in whiteness in a place that had been happy but was – at any rate not so that it coincided with my flickering passage through it – not so happy now? I had the sense throughout my visit that I had been cut back so that I might regrow, and that the cut was speculative.

Like many things that are over though it seems at the time that they will never be, that period has struck deep roots in memory. It is on the turn inside my head. For all its white silence, that month and a half almost wholly under snow in the North-East, just up to the time of snowdrops, is expanding still and turning itself over under its quiet, like a sleeper, becoming something, perhaps.

I suppose that the person whom I met again and again day over day who wasn’t there upon the stair was myself, and that I did not like being snowed in with her. By the end, I was talking to the hot-water bottles and giving names to the taps. My bar of translucent pink soap had become the emblem of my time there and I washed with it angrily so as to wear away the hours of day to a sliver over the white cloudy lukewarm bathwater, in the house in the white silencing snow.

The snow did bear light within its reign though not the light that I had projected when I thought in advance of that sequestration in the North-East. I had thought that the post-operative period alone in the unknown countryside would cause things to settle and to calm, showing me thereby what I should do next in my life.

The phosphorescent snow bore some kind of reveal in its soft train when it melted, showing me that yet again what I had done was take an artificial position, in some pain, attempted to deal with it alone, got frozen in, waited for a rainy day and then – seen no option but flight.