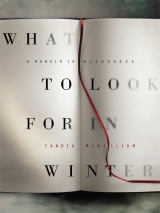

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Chapter 2: Saw/See

I thought that I would take two lenses of time, one from after finishing the first part of this memoir, and one from now, here on Colonsay, this place that combines the present with the far personal past, and try to adjust them so as to see through or even catch some light to partly melt the snowy cover that lay across some of the bleaker branches or wider wastes of the earlier chapters.

There is a newish convention, that goes against any observation or experience of life that I have, that characteristics and narrative must not be ambivalent or ambiguous, or the reader will be confused. Since this is the condition of language itself, we are talking here about books brought to the level of nursery school reports, or of bad film synopses.

Ambiguity is there at all times. Tolstoy and Proust catch it. In triumph lies defeat, in consummation boredom, in despair self-watchfulness and the resurrection of attention. When I was told that I would never see my mother again, I felt not one but many things. As well as the confirmation that I was now unaccompanied, as well as the questions as to the cause of her death, that might not be asked, there was the unpleasant gratification of the event, that could not be admitted, but was nonetheless an attribute of that time. I knew that, for this probably very short time to come, no one would be unpleasant to me for being peculiar or showing off, or being fat, and that I would for a time be at the focus of something. In neither case was I in fact especially rewarded along the lines I had envisaged as parallel to feeling that harsh deep abandonedness. But I certainly knew that there was never going to be the simplicity and clarity I had previously imagined went along with growing up.

And surely it must grow one up remarkably, becoming motherless as quite a small child? Yes and no, of course. I have always tried to think how another person would behave, given my circumstances. I may think I can imagine this, but I cannot. Can I? Can you? I can think how a character taken from a book would behave with more success than I might think how a friend or a member of my family might behave. I can guess, and I may be right, or I might be confounded, I cannot even imagine how I might behave. I just behave.

I may think that I have taken stock, but what will most likely have happened is that curdling mixture of inanition and violence that have characterised my life and that are more usual than either literature or our understanding of life conventionally allow. For if we were fully conscious of this catch all the time, it would be as impossible to live as if we were able continually to look at that glaring fact of mortality against which we have to fold our time away, and from which we must avert healthy eyes.

Our character and our personalities lie in the torsions between ambiguities, no matter how Romanly straight our apparent, enacted, nature. In fiction too it is these electrifyingly unsmoothed characters who most live, as against characters taken from stock. In life we are drawn often to people as unlike ourselves as possible. That compensating attraction means we outsource traits we do not possess but require. I twine like a convolvulus about people who apparently know their own minds. In very few, but how beloved, cases, have I been right.

As for such people as pride themselves on self-knowledge, it is as with those who admit with sheepish self-tenderness that they pride themselves upon their honesty. They are playing to their own gallery.

Some people do act without reflecting. They may be stupid, very brave or extremely well trained. Almost without exception there will be a sadness about them at the weight of those closed chambers and tightly stifled reflective surfaces within. Unless they are beyond privilege naïve, they are made jumpy by the untested and will not allow of the unknown. They curtail their vision with the red denial of a butcher insisting that his bloody crib is not an ox’s carcass.

It is still raining in the Inner Hebrides in early May 2009. Through the water pipes I hear the upstairs toddler and through the window that is opposite the one that steams with garden green, I am aware – the window is at my back – of a conflict of rooftops, one curving over an arm of the house, the others sheltering its kitchen and offices, finished with softly bent pale lead and tiled with slate as deeply purple as pigeons. Everything is wet, the window as well. I am conscious of this sight because I have in my life seen it so often, so often that I am not sure that I need to see it now, such that I am saving my eyes for this screen rather than for the window whose view I am describing as I tap laboriously trying to elicit some scene from the past in order more clearly to stalk the truth like a white hare through the thaw, although I am pledged to the idea that truth about one’s own life melts, or flits, again and again just as you breathe on it.

Not long after I spoke the words ‘Let’s see’, just after my birthday, I had the first and so far only grand mal fit of my life. It felt as though I were an old-fashioned camera, into which innumerable heavy lenses were being inserted one after another, each at a different and more acute setting, and then as quickly and clatteringly taken out. The world weighed heavy, shivered, fluctuated, jerked, grew too heavy utterly and fell to the ground in pieces as though my limbs were dud and chopped like fallen empty armour.

It felt not unlike the aftermath of drinking till blackout and indeed Fram, who saw me in hospital, at first wondered if I had been. For me the consequence of taking one drink is that I cannot stop for ever longer and more deeply degrading periods afterwards. If only it had been that simple. I do not know why my brain took this great insult and gave me a fit. I know that I was saved from something worse by my god-daughter, who was with me, and who rang an ambulance because she was afraid for both of us. She told me later, doing an imitation, that I hid from the ambulance men, and questioned their choice of shoes for hospital. I can remember nothing, just as after a blackout.

It was in A & E that I came to. I felt as though I was in the middle of a painting of a deathbed. I lay on a foreshortened bed off which I hung in a curtained space, with, to one side, a slim young man with striped hair in a stream like Beethoven running, and at the foot a group of young people in summery motley, cotton, stripes, lace, shawls, hoods. Two of them were blond and one had the dark hair and eyes of a young knight in a painting from the Renaissance. I remember thinking all that, the Beethoven, the clothes, the similarity to a painting, and I thought at that same moment that if I had had a stroke I was still myself within. I was frightened. I was worried that I had disrupted a number of people’s days. I was embarrassed. I wondered how I could ever make it up to the children. There was also the startling fact that I could see.

I knew that I could not simply be polite and get out of this one. Something had occurred and the event, whatever it was, would not go away. I could not pretend that it had not happened. I was unable to remember that morning save for two detailed things. My first visitor that Sunday morning had been my daughter’s friend Edward Behrens, later to be the Italian Renaissance figure at the foot of the bed in A & E. We had discussed the mushrooming scene in Anna Karenina, the moment when Tolstoy says that you could almost hear the grass growing, and describes a blade of grass that has pierced its way through a grey-green leaf of, I think, aspen. I said that I wanted to learn Russian and we discussed audio systems of teaching oneself a language. I suspected that I would be too passive to compensate for the absence of a teacher. Something was wrong that morning and I sent Behr on his way. It was a sunny day in Chelsea. He was off to lunch with friends. I felt as though the inside of my body were heating up and going to split my skin. I was afraid that I might be sick or worse in front of this clean young man who has been so good to me over these blind years.

The next thing I remember is that my god-daughter Flora appeared in the dark of the hall at that flat. Its lighting was faint, its mood brown. The hall featured several subfusc contemporary oil paintings of Italian street scenes and a large bronze sculpture of a multiple demonic head that cast a horned shadow. When Flora arrived, over six foot two and thin as grasses in wind, she stood in the light of the front door and I saw her in the kind of intense detail that came to me often when I was very drunk and that was one of the reasons why I continued to explain my drinking to myself – that crack of clear high vision before passing out. It felt a bit like some kind of love, or doting.

I saw Flora heightened, as even more porelessly exquisite than her genes and mien have made her. She might have been the last thing I ever saw. For all she knew, she was. I scared her terribly. My last mortal sight before the new, fitting, world was a young woman of disproportionate height and slenderness in the lace and pinny of a Victorian child, complete with bloomers and smock. Below this stretched her long white legs, ending with ballet pumps. Her chiselled pale blonde head is perhaps a ninth of the length of the rest of her. Her hands waved like white cloth under water. She looks at the world through specs. God knows what she saw.

And then, for me, nothing. For poor Flora, panic and telephone calls, chasing to ground diverse family members, keys, messages, toothbrush, the intimate chores of sudden event. We get no rehearsal. She did it all with the kind of competence that can come only naturally.

I knew that something had happened and was possessed by the idea that it was a stroke. McWilliams die young of strokes, especially fat McWilliams. Thin ones die young of heart attack.

In the hospital Flora said, ‘Fram and Minoo are coming. Fram says everything will be all right.’ Fram is the human whom I always believe. I hand to him inappropriately profound knowledge and sagacity, authority. It is burdensome for any mortal and worse for one as sceptical and intelligent. Nonetheless, all I wanted was Fram’s assurance and he will have known that. The same goes for our son Minoo.

Beethoven said, ‘You are in the best place, Candia. We do not think it is a stroke. As far as we can see, you seem to have had a grand mal fit.’

He knew what to say. He saw the main fear, addressed and dismissed it, and supplied as much fact as he was able. He also, with some generosity, said something sensible and kind about the ever higher doses of antipsychotic drugs I had been prescribed with a view to causing my brain to have some sort of benevolent convulsion that might, as had sometimes been suggested by certain controlled cases and had been written about in a couple of academic papers, alleviate my blepharospasm. What Beethoven said was mild, intelligent and noncommittal.

By now I realised Beethoven was in fact my GP and he knew me well enough to tell me the truth. It was a relief to be understood, to be treated as myself. He spoke sanely and the relief, that of finding myself in a sane, if frightening, world, was great. It is Beethoven, of all the first wave of doctors, who has helped the most. How frustrating then that his skills – common sense, empathy, compassion, practical doctoring – are undervalued in an NHS crippled by bureaucratic failure to communicate from the most basic to the most elevated levels and awash with specialisms that take no account of one another.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ said my GP. ‘You must go to Don Carlos.’

I heard it with gratitude as a sentence from the lost world, from which I had been cut off by a mixture of illness and my own self-isolation. Long before I had become ill, I had become almost incapable of going out. But this was a healthy sentence and I heard it gratefully. I also realised that very few people knew how odd and shy I now was and that the thought of going out at all was nearly impossible, that my automatic response to any invitation or suggestion was ‘No’. I wanted to be connected, but had forgotten the flags to hoist to make the right signals.

I love Don Carlos, the darkness of the bass voices, the problems of conscience and power, the fear that fills it, the intractable love-muddle. All the stuff that my father disliked about it, I love. It makes me feel that nothing cannot be thought through to the sound of it, though actually my father might have said one is feeling rather than thinking. It thickens the air and my father liked his mental air clear although he could do turbid domestic silences and was a retired master of brooding absence. He did these for my mother, not my stepmother, who was certainly a better wife for him. I wonder how often in a day I think, in three contexts, that last phrase? So much so that the ease with which I use it to hurt myself bears reining in. Since my husbands’ wives are not there to hurt me, why do I sink to using the thought of them to do so?

Because, perhaps, it feels familiar.

The days that followed in hospital I still cannot make out. I felt like an animal and I knew that I was dying. I could not explain this to people. I was acutely worried about my daughter, who was already in a bad way as her ex-boyfriend had recently died in his early twenties of anoxia. When I got to a ward, my diagnosis was posted on my bed. It said that I had anoxia. Clem was wobbly and I couldn’t properly help. I was rigged up to tubes and looked unconvincing as a comforter. In American English a comforter is what we in Britain call an eiderdown or quilt or in Scotland it’s a downy. In the Prayer Book, the Comforter is the Holy Ghost. I looked more like an eiderdown.

I kept trying to make things better for people and failing. I had the powerful sense that I was being a nuisance. It seemed that I could not make things clear to anybody.

I am absolutely certain that none of this is unusual when you find yourself in hospital. When it comes to hospital Omne ignotum pro terrore says it all. Why was I so sure I was going to die? Was I attention-seeking? At first I feared I might be. I determined to be as mouselike as I could. It is a thing I do, a McWilliamish habit. We go humble and invisible. It drives Fram mad. I see why. But it’s what fear brings out in me.

I didn’t think precisely that Death would pass me over on his ward calls if I were polite and self-effacing enough. I thought that the nurses wouldn’t resent me. It was as pathetic as that. And why should nurses resent their patients? Why are they nurses if they do that? I don’t know, but these ones, or so I thought, did. I have reason now to think that I wasn’t wrong, but let that come later.

It was a high-dependency ward, intensive care. The standard of care was considerable given the intensity of demand. Cleanliness was rigorously observed. My older son came in, his beauty like a bonfire. He loved washing his hands with the antibacterial gel at the end of the bed. It made him smile the naughty smile that I had forgotten till my children restarted it: it was my mother’s. His green eyes went slanty and flashed jokes to me. I loved looking at him.

I loved looking at him.

In that ward, after that fit, for some days, I could see. It was as though lightning had struck with the fit and released me from the dark wooden trunk that had grown round me, blinding and stiffening me. I was shocked back to seeing for a bit.

It was lucky that I could see at the start as there is no point being unable to in an intensive care ward; there is such a lot to fall over, much of it affixed to or into people.

It was a mixed ward. It was arranged around death, of course, but more explicitly than usual in wards that are less acute. Beds did come free while I was there, if I can put it like that. Curtains and pulleys were used with seamanlike efficiency and speed. Two of us could not die in spite of efforts in that direction. Each was fighting according, I suppose, to their habit. To my right lay an elderly physician called Michael. He was very ill, handsome still, and over eighty-five. He asked for very little though one time in the night he asked for something for the pain. It did not come for a long time. He had been a consultant. He did not once use swagger or bullying or any of the tricks we saw daily put to good use by the young, fit, consultants on their ward rounds.

Why cannot doctors be kinder to doctors? What is it that makes them forget that to know what is happening to you is not to be relieved of pain or of fear? Michael had a younger wife and a son who was still in the sixth form at his Central London school. Not long ago he must have known the comforts of love, the warmth of talk.

Necessarily, the visiting hours were strict. He saw his wife most evenings for a short while. She was attractive, blonde, cool, American; an academic or even a doctor? They had no privacy. He was dying. She was losing her husband, her son’s father. You do not marry a man far older than yourself without thinking of these things.

Nor do you marry a much older man unless you want the support of his seniority. Even sick to death, he was not reduced. Unlike many strong personalities close to death, he had not become pure will. He declared no faith and spoke little. We had one stilted conversation about schools for boys in London, which was how I learned about his son. We were sleeping not four feet apart.

I spent some of the nights planning a short story set in a ward like this. I was inspected by a serious, gentle Middle-European neurologist from time to time. A charismatic professor swooped sexily through but hardly stopped at me. The comely trainee doctors might have been his due. A hierarchy of desire was evident in the doctoring and nursing staff. After certain visits, the air was left with that sense that a personage has passed, a star shed its starry dust.

We lay in our beds beyond desire.

The other person who was dying was taking it another way, not with Michael’s enduring silentness. She was opposite me and I feared her and feared for her. She was afraid of her own bowels with which she was locked in mortal wrangle. She wanted to catch them before they betrayed her. I had now seen this in two people I loved as they died, my grandmother and my friend Rosa, another uncomforted doctor.

Vi was dying like a little child unjustly shut in a cupboard. She howled to be let out. The cupboard wasn’t her dying, it was her own body. Every few minutes she howled out, ‘It’s me bahls.’ She was as afraid of her shit as of her end.

She called for a nurse at regular intervals all night in the slack light of the dimmed ward. A disdainful call would come over to her from the nursing station. I didn’t realise it yet, but almost every high dependency ward has a lady like Vi, an old-fashioned old woman become a stranded little girl again, howling across to the other shore. It’s the reaction to such women that varies, I was to learn later. But Vi was a nuisance and a bore and because she was reduced to an animal there was no chance for her to change; or that’s how she was dealt with on that ward.

I mentioned her to Fram and he told me just to think about something else, to tune it out. He had misunderstood me. It wasn’t that I was upset by her, I was upset for her. That made him crosser. Why did I have these fantasies of helpfulness when I myself was quite clearly helpless?

I did indeed mismanage that visit to hospital. I don’t know quite how I got it so wrong, but I did. I was full of fear continually. I wasn’t too afraid of dying because I almost thought that I had. From time to time I was put on a trolley or into a chair and taken for tests.

These were various and not uninteresting. Some I had been subject to before during the early days of hunting down my blepharospasm. Electrodes were glued into my long hair as close to the scalp as they could go. My brain answered various questions. My body got heavier and heavier. It became like a stone upon my spirit. I’ve always been prone to treat my body like a stranger into whom I’m surprised to have bumped. During this stay in hospital it became a bit like an uninvited guest.

In the window of my workroom here on Colonsay, my small travelling radio, which I had turned off earlier because the rain was making its sound crunchy, has burst spontaneously into pure uncompromised sound. It is – I know it at once – the Adagio of Brahms’s Violin Concerto. The tune goes sinuously and excruciatingly lovingly to its quiet end.

It’s the first outing of a new recording by Valery Gergiev, so new, says, the radio, that it’s ‘still quivering’.

The Brahms Violin Concerto is for me a Colonsay piece of music. When we were almost still children, and the youngest children were properly small, we listened to it on Sunday mornings in summer. Electricity was trembly and contingent and the recording was on a long-playing record, played on a gramophone of home-made construction. To me, then, it was music of potential, of how my life would be, and of the present, new, familial, romance, the children, the parents, the smell of cooking meat, Papa sipping Madeira from a silver cup, so the drink smelt of damsons and tarnish, quite often a fire in spite of the bright summer light, the fire deep in the grate, its flames pale pink and blue, and a scent of spicy rose petals, never in this soft air completely crisp, in a thin deep bowl from China, and of rich dampness from unstopping rain that washed and washed the sky so that you could not believe its whiteness when eventually the rain was drawn aside. The books in Colonsay House hold water, sweet water unlike that salt library in the West Indies when I was twenty-one and could see though was blind to so much.

Of course I was perfecting things, turning them into scenes or tableaux or stories from a tale of happy families, and by so doing making them fragile; but the memory is not frangible. Later the parents parted and we have all grown older and too many and too few words have in some cases been spoken, but it is not nothing that, in a week or so, two of the sisters and Alexander and I will be here in the house, Alexander and Katie and Caroline with their marriages intact and their children growing, and all of us no doubt would be struck like damp matches in a different phosphoric way by those long notes on the violin, after one or two or three strikes of the soft tight bow.

What I suppose I should take from this gift in sound and the light it has lent to the story I was telling about this last year’s first unilluminating brush with hospital fear is that all my life I have been far too ready to leave, irreversibly.

I was ready to die during that time in hospital, pushing forward to volunteer for it, to get it over with although we may be fairly sure that nothing comes after that last crazily obliging rush to self-effacement if we succumb to enacting it. I just didn’t want to be in the way. No wonder I exasperated my family.

I was so afraid of small things that I was ready to jettison the great ones. On account of not wanting to be in the way, of not wanting to present a problem that could not be solved by these intelligent doctors, I wanted to tidy myself away.

On account of not understanding what was happening within my father’s mind, I decided to leave his house as though I had never been, because I knew, as I understood it, that things would be better without me and was then resentful that it was as though I had never been.

What does the Brahms Adagio mean now?

It means itself. And after it has passed there comes that formal silence full of promise in which one lies refined and maybe hopeful.

Tomorrow, on the island, there is to be the funeral of a man who died, full of years, on Sunday. There is nowhere to die here but at home.

You are cared for in your house. There is a hospital, but it is a flight away, on the mainland.

Katie has been to say goodnight to me. She has been working in Papa’s old workshop. It is now, on Wednesdays and Fridays, to fit in with boat times and the open days of the big house garden, a cafeteria, offering home-made lunch and tea. Today she made rhubarb and ginger jam before her office day began. Her office days are never alike. Many of them are spent fixing things, making things from other things. She and her siblings are good with orphaned objects. They can darn and weld and splice. They have learned never to waste. You don’t when everything has to come from outside. You adapt. Katie still dances in a red velvet skirt that she made as a schoolgirl from curtains. The boys wear Papa’s kilts that were his father’s. Papa wears his father’s suits.

The drying-up cloths to the right of the stove hang from struts in the shape of goosenecks made by Papa from inboard struts of wooden boats. Katie keeps the kindling William splits in a fish box the sea washed up and grows her tomatoes in others like it. Colonsay gets the afterwash of the world’s wastefulness. One year it was hundreds and hundreds of pastel toothbrushes washed up on the white sand with the gummy wrack. This flat is full of things my not-siblings made as children, displays of collected shells under glass, glued scraps of botanical prints, a wicker stool.

In the laundry cupboard rag store are the remains of nursery bath-mats with reversible silhouetted scenes of blue geese, pink bears, from the 1930s. The linen is stitched with laundry-marks from the 1950s. My favourite shirt is made of Aertex and was bought at Eton for Papa’s father to play fives in; it is laundry-marked at the neck ‘1921’. It is made of holes, held together, right enough.

I wasn’t handy, but I was visual. Papa gave me small jobs such as the making of nameplates for Alexander’s model steamship, powered by the purple spirits you used to have to sign the poison-book for. I could choose the name. It was Methalina. For several school holidays, I restored some mustard-coloured pâpier-maché globes, one sidereal, one terrestrial, and did it so badly that the earth stuck in its axis because I had wodged on so much layered papery weight on one side over the split in the tropics. I spoiled its first eggy smoothness with my damaging mending. Still Papa kept on entrusting things to me.

The constructive refusal to accept that anything is ready to be thrown out makes for transmission of what feels like memory because things stay around. How good is consumerism for memory? Part of its point is that it makes you think that the next set of memories will be better if only you buy the things with which to make them. But you cannot arrange for memory like that.

Papa’s father had a routine that breaks the heart. It is surprising that it did not break his back. He carried a sack of cement daily miles over bog and briar down to the sea where there is a very small island close into the shore, the size of, say, a garden shed, called Eilean Olmsa. There he poured his sack into the sea. Was the idea to form an attachment? What was the purpose? Did he feel that days spent thus must add up to something in the face of the assured erosion that awaits us all?

In a romantically pragmatic family, that is in a family whose romance is with pragmatism, is that not a sad thing to do, a quest defeated at its inception? Did he plan it or did it just become a habit? What, beyond his wife, was he wishing not to be with?

Just before the sky grew its evening grey over the last twenty minutes, there was a pallid but clear and warm ten minutes of pure light.

The two big cedars that catch light were wet with the rain of three days and nights, wettest where the trunks cleave inwards, paler on the convexities, their chiffony bark clinging like drapery to legs. The trees seemed – I can see more clearly as the light goes; something stops hurting in my eyes – to be holding tall twisting dancers within themselves.

The lamb William found orphaned on the north of the island has been accepted, dressed in the fleece of her dead offspring, by its foster mother. The ewe whose eyes were taken by a raven has been destroyed.

Just after extreme events, I see as I peer at these alignments of experience, I feel that something may be about to come, at last, under my control. That formal feeling comes. But I couldn’t stick even a paper world together.

It is the next morning. The sky in the north has light until the stars can be seen. The moon was up in a lilac sky pale as day after the rain clouds cleared during the night. I got up twice from excitement at the lightness and could look the pink moon in the face the first clear time. The second time the winds were fighting it out while I waited for the kettle to boil and the sky had thickened to a duskier blue.

My machine for listening to talking books hasn’t yet arrived, so I was reduced to my own company. I tried to practise the emptying of mind – known trickily as ‘mindfulness’—that many doctors and their professional substrates have recommended. It’s easier here than in London. I listened to the water rushing together, the stream below the lawns, the rain, the burns in spate that could only just not be heard at the edge of my consciousness. I like to listen to what isn’t stated. It’s one of the great pleasures of reading.

Katie has just come in to where I am working. She starts in the office at 8.30, does her email and her mail (when there’s been a boat) and does what the day asks of her, from ironing sixty sheets and walking dogs to double-entry bookkeeping and arguing with the state about heating for pensioners or school meals for the island’s nine schoolchildren.

She comes, it seems, sideways on into a room. This is what it looks like because she is narrow and stands with her head on one side. She is still but hardly ever at rest. She carries her knife on its lanyard around her waist. Her plait is silvering. She is going out into the garden to cut white flowers for the funeral, but, she enquires, do I think that colour would be disrespectful? The red and pink rhododendrons are at their best now.