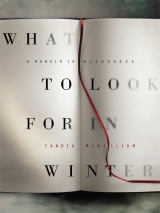

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Enduring town life but not attached to it, Katie was delighted to be asked by her brother Alexander to come and live on Colonsay and work with him. I told her she must keep a diary. Colonsay isn’t like anywhere else at all. There’s an adventure every day. You could write a poem every morning and every night. I would like to live there for a good stretch of my life. I began to worry that Katie would get sad when the days got shorter and darkness came down at three, but she has the great gift of Arachne, and every minute is filled. William has now followed his wife to the island. He works as woodman, binman, soothant, impresario, baker.

The topography of the island offers all terrains in little, as though it were an ideal or invented place. It has its great peak, just under 500 feet, its isolated lochs, its whistling, golden, silver, black and pink sands, its cowrie beach and its fulmars’ crags; it has its deserted blackhouses and its wild flags, its own orchid, Spiranthes romanzoffiana, its fairy rings, its Viking burial ship, its standing stones, its overdressed choughs that look ready for town; it is the only place where herons nest on the ground and it has a pair of nesting golden eagles. Its turf is dense and full of wild flowers, including the smallest rose, the pimpinellifolia.

The islanders peopled my childhood, my growing-up, my middle age; some have left, many more have died, several tragically, needlessly. Some, over the years, have been brave enough to dance with me, or even come south to toast my wedded bliss. From the residents of Colonsay I have received steadiness, grace, jokes, music, irony, continuity in the sort of quantity that I would hope to offer a child, or, for that matter, a dumb animal. I have been privileged in this.

There is no avoiding boats on an island. The miracle of the ferry, for as long as I was at boarding school and then at university, was that there might be periods for as long as three weeks when the island was stormbound and the Columba could not get through. This must have been both worrying and tedious for all the adults concerned, but I was having a honeymoon with infancy and felt it bliss to be stuck safe at home, with its routines and rules and habits.

We did run out of food. We tell people we ate curried dog food. I can’t remember if it’s true. It might as well have been. We did eat any quantity of a magnificently Scots viand, buyable in bulk, named SwelFood. It had a connection with the vegetable kingdom. It lived up to its name should you add water. A little heat improved things. I ate and ate on Colonsay and, though not lean, like the others, I didn’t get fat, because I was living a life beyond books, though not without them.

I have never quite got over a bad tic I taught myself, very likely unnecessarily, under my stepmother Christine’s regime – to leap up as soon as one heard footsteps approach, to hide one’s book, and ‘look busy’. I didn’t do that much on Colonsay, at Colonsay, in Colonsay. The nature of my anxiety changed. I wished to fit in. In this I lost bits of myself. This was all my own fault. I think the Howards wanted me as me, if they thought about it at all.

When people look knowing and talk about the popular music of their childhood, I can honestly refer to both my childhoods, in Edinburgh, and on Colonsay, and look blank. When the electricity worked on Colonsay, the gramophone played classical music. Quite by chance I had lit on another musical household. To reach the drawing room from the front hall, you had to go through a curved room called the corridor-room; there was a smiley bison with a centre parting in his horns over the pianola that had sheets taken from Paderewski’s own playing of Chopin, and a piano that we sang around. Mum or Caroline played. It was from the corridor-room gramophone that I first learned to listen for the style of a conductor, though frequently the tempi must have been affected by the wind or the rain outside. We listened a lot, together, to music. I remember the Brahms Violin Concerto and his Hungarian dances, the Mozart Coronation Mass and Litanie Lauretanae, The Marriage of Figaro and The Magic Flute, and Haydn and Boccherini. Just sometimes, Edith Piaf, whom Mum and Papa had seen in Paris. No Messiaen, no Mahler, no Russians, no Wagner, all of whom I love, but came to later. Papa, as on every ‘cultivated’ topic, knows more than he affects to know. He is a natural teacher, the only man I would allow near my younger son with a fretsaw, or near me with an explanation (all done in salt cellars and napkin rings) of how the universe works or what diatonics are. He is intriguing for many reasons. He has not grown old where old means bitter or incurious. Of course he repeats himself. That is because we force him to. We say, ‘Pop, Pop, do the one about…’

We are in our fifties and forties, he halfway through his eighties. I’m lucky to have been caught in his slipstream (he will correct the term, no doubt).

His brother Barnaby, who is perhaps eighty-two, was dying last year. He had had three wives, three children, seven stepchildren. Papa went over to St Louis, where Barnaby has made his own version of Colonsay, to say farewell for good to his younger brother. Papa officially hates death. Barnaby’s nurse fell in love with him. Instead of a funeral, there was a wedding. Barnaby shares his brother’s good looks, though without the beard. Height, black hair, now white but still thick, and cruel blue eyes belied by that smile wide as a wolf’s and as perturbingly white. Papa smiles while he is working, biting down on a small piece of his tongue. His children and grandchildren do it too.

They all carry multifunctional knives around their waists on lanyards, though have had to rethink this since airports grew difficult. Each one’s knife is of great sentimental value, having been given as a reward when, one by one, the children learned to sail their respective wooden boats around the tiny island in the loch.

I’ve never been in danger of possessing such a knife.

The Howard children were sent away to school considerably later than many children of their background, as it might conventionally be imagined. All the children owe their general knowledge and handwriting, their sense of lore and their manner of keeping things shipshape to their governess, Val, who had also been governess to their mother and her six siblings. The big house is full of things Val made with the children: tables with glass tops covering labelled shells gathered during afternoon lessons and laid on old green velvet; lists of birds seen and illustrated; children’s books carefully inscribed in the same fluent rounded hand as each child came to learn it. Val never taught me but the others had that kind of skater’s grace to elide this so that I might sink my roots deeper into the family myth.

Yet I was unconsciously deceiving myself on far too many levels. The fact remains that there are six Howard children, whom I love, and that they are not my siblings. Nor are their parents mine, though it is my belief that I love their father very much as people do love their fathers, as far as I can see it. It is far too late to untangle anything that goes so deep, but it is not too late to be clear about who is whose. I speak in this apparently chilly dissecting sort of voice on account only of knowing that it is with the precise naming of things that my sight will, if it will, return; and that the truth matters.

It is with reference to boats that I am able, perhaps, to express the intensity of my affection for this family. I trust my life to each member of it and have been hauled from the possibility of a watery grave, as has my younger son, by their strong arms more often than I can admit. (Minoo and I have spindly, useless arms.) Life on Colonsay is lived, very considerably, on boats. Given the chance I would rather step out of a boat than into one, be this into a harbour, which has happened countless times in Colonsay (and once in Tonga), or at sea, or into a loch (or into the South Pacific, where I hadn’t a Howard with me and which comes later). Perhaps at root there is little higher one may say of another individual with whom one has spent a mort of time than that one feels safe with them. The Howards make me feel physically safe, which is a state I achieve in few other circumstances. What these circumstances are will make itself plain to readers.

It was from Colonsay that Katie was first married at the age of seventeen and a half, in her wedding dress ironed by Val. Rosa and I made bowls of philadelphus and daisies. There was a marquee and the honeymoon was taken on the Isle of Barra.

In the photographs we all, including the grown-ups, look like children.

Marriage was still at the time the suitable terminus of the story of a childhood. Girls were married ‘from the nursery’, like trees taken for grafting.

During the time we were at Cambridge together, Katie and I were, I think, unsure of what narrative to follow. The times were changing, but nothing like as swiftly as retrospect might have you think. Girton was quite as sequestered and well-behaved as Sherborne School for Girls had been. Many of my contemporaries in college arrived engaged and left after their degree to enter into marriage.

The first night in the dining hall at Girton, which is a red Victorian Gothic structure, designed by Waterhouse, three miles outside Cambridge on the Cherry Hinton Road, a sturdy pink blancmange was served; I said I wouldn’t have any, thanks, and a shiver went down the table.

Later I sustained two approaches, one from a quietly spoken American girl who turned out to live just off Washington Square with her grandmother and two giant poodles and who became a friend for life, Miss Sarah Montague, gymkhana star and radio performer; the other from a girl I regret having lost touch with, who said, ‘You went to fucking public school, didn’t you?’

I think the truth is that I only went to fucking public school because my mother was dead, and that is the answer to the question I asked some chapters ago, would it all have happened if I had stayed at home? I wouldn’t have fucking talked like this. I might have talked like fucking that, and that in itself might have been a great big fucking relief. Not that, actually, all Scots do swear all the time, nor pace some English critics, does that brilliant writer James Kelman use such language, save where to do so holds to the truth.

If I had stayed at home, I wouldn’t have talked like this and I might have married a nice Scots boy who really could dance (though in the East Coast fashion) and we might have settled down to the couthie Edinburgh life for which, I think, I hanker so, now that I definitively have not lived it.

Scotland itself is zigzagged with strifes and loyalties, with roads that wind north in listlessness, desolation and ancient war; there are many sects and septs of Presbyterianism and many families who raise a glass to the king over the water. I won’t here go into Rangers and Celtic, for I’m ignorant, but so little is the country, so small its population, so deep its habit of talk and of remembrance, that the past lies over and within everything. While it is a hard fact that Papa’s great-grandfather received the Island of Colonsay in lieu of payment of a lapsed debt by Sir John McNeil, it is also true that if to own a boat, as the vulgarism goes, is to stand in a shower tearing up fifty-pound notes, to inherit an island is to stand in a maelstrom doing much the same, with added responsibilities for its human residents. Papa was born in South Audley Street to parents of improbable wealth, deriving in the main from the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Hudson’s Bay Company. His great-grandfather endowed McGill University and Papa said once that he seemed to remember a lintel over a door in the ‘Old Man’s’ house in Montreal that was made of solid gold. His great-grandfather, Donald Smith, became first High Commisioner of Canada and later Lord Strathcona (Gaelic for Glencoe which he also owned) and Mount Royal (which is just Montreal). Goodness knows if this lintel was a metaphor or what he literally saw, but Papa’s own life has been entirely unembittered, as he saw most things except for Colonsay go. He is a born master craftsman.

The words ‘private island’ come nowhere near Colonsay; it is not a plaything but a society, and most of the boats, houses, cars that pertain to the family that accidentally presides amid it with patience, beneficence and nothing short of love, are held together, bodged in some way. Papa is a genius at bodging. So are his children. It’s my sense that they don’t really like things that do not need fixing.

When we were younger, Katie, Caro and I shared clothes. Jane was careful and neat and very sensibly kept us off. Caro had a red jumper knitted for her by Val, Katie a becoming cream jumper knitted by her grandmother with a repeat motif of the Strathcona crest, a beaver chewing its way through a log. I had two jerseys, one of which I’d received for Christmas from Mum and Papa so it was sacred and came out only for evening wear. My other jumper was grey, knitted on needles the size of rolling pins, edged in grey velvet ribbon, large enough for a shire horse and had been thrown out by Daniel Day-Lewis, the weedy younger brother of our friend Tamasin. No. I don’t know where it is now. It disappeared with my dried-out and reassembled lobster, some old love letters, and the Clarendon Press George Herbert, all of which were by my bed, when I ‘grew up’ and Alex and his wife Jane took over the house.

There is a strong bohemian streak in the Howards. Papa’s mother, confusingly known as Oma, really could paint and her many swift oil sketches of the island catch it just so. Papa was brought up with Peter Ustinov, whose mother, Nadia Benois, used to paint with Oma. There are two ‘reciprocal’ paintings made by the two women on a summer day on the island in the nineteen-thirties that hang in the corridor-room on Colonsay. Tulips in a vase, dropped-waist dresses, a departed Hebridean afternoon seen through differing eyes. Many of the Howards’ close relations are artists; one, Linda Kitson, who briefly married her cousin, Papa’s brother Barnaby, was a Falklands War artist. Papa’s sister Didon was a creator in her every gesture and she leaves girl twins who have the very same trait; one of them, lying in Barcelona, felled in her forties by a stroke, is literally drawing herself out of it with pencil and paper. The Howards are not spoilt. Their affection for things is greatly enhanced when that thing is to some degree damaged or, even better, hopelessly broken.

It is my private belief that Papa rather resents things that work perfectly first time. I don’t mean he sabotages them, but he perceives less of a challenge in the spanking new than in the clapped-out old. He is without doubt an artist in wood and metal. It was a sad day when he moved out of the big house and his entire run of Wooden Boat magazine was on the line. He had first subscribed to it aged thirteen. In the end it went, though he has kept the squared notebooks in which he draws inventions and improvements upon machines that have caught his attention. One of the most happy days of my second childhood was spent not actually on Colonsay but off the old A40 in a disused church with Papa, Katie and Caro; we were there to meet one of Papa’s innumerable correspondents. His family used to say of Papa that he kept a steamboat hidden on most canals as other men keep mistresses, but that day we were privileged to enter the largest steam-driven Wurlitzer in the known world. We climbed inside its entrails, saw the real coconut husks that made clip-clop sounds for the movies, and Caro was allowed to play it while Katie and I stood inside and watched the bellows do their elephantine work. Papa, although he is, as I have said, a man resistant to the soapier sides of faith, is a soul whom it is a pleasure to see transported, whether by a Wurlitzer, the Queen of the Night, the way the bark grows on eucalyptus trees, or when a rope goes clean around a cleat.

It is this feeling of docking cleanly that grows more elusive with blindness. I will, if I may, give an account of my mornings at this time of my life. I get up at six, run a bath by ear, turn it off, feel for my electric toothbrush, load it with toothpaste, making sure by smell the toothpaste is not foot cream, do my teeth, get into the cardigan that I know hangs from the bathroom door, go into the room where the cats’ litter trays are kept, find a roll of dustbin bags, somehow discover the mouth of each one and put one inside the other, in case of horrible leaks, fill these with the used litter and any old cat food and the newspaper the cat dishes sit on, give the cats clean litter, wash their dishes and dry them, put clean food into each dish, making sure not to spill any cat food on my hands or I shall smell it all day. I then take the bin bag downstairs, holding the grabs and banisters, to the catacombs of this Victorian house, undo by feel three deadlocks and put the full bin bag in the appropriate dustbin. I re-shut the deadlocks and move slowly towards the kitchen where I know how everything is stowed, though I still fall. I half fill the kettle (I can do this by weight), take the coffee from the upper shelf in the freezer door, shake about as much coffee as a squirrel’s tail would weigh into the cafetière, wait for the water to boil, pour it on to the coffee grounds and commence my daily quarrel with the plunger. By now it will be 7.20 and my bath will be of any temperature at all, so that’s a surprise to look forward to. When first I became blind I was determined to be well groomed, something I have never in my life been before. I’m not sure it’s worked, although I know that I am clean. On my shelves however, await the jumpers of a well-groomed blind woman, each arranged in its own bag with lavender or cinnamon or clove (sovereign historic but useless remedy against moth). My jumpers are arranged from white to black through all the misty colours of grey and pink and blue and lavender and olive that I wear, the naturally occurring dyes of Scotland, where my jumpers were born. In its way my cupboard of jumpers is like Des Esseintes’s organ of perfumes in Huysmans’s Against Nature. In another way it’s just me trying hard to kill two birds with one stone; that is magically to become tidy and, even more magically, to unbecome blind. I did the colour-coding holding open my eyes with my left hand from the top of my forehead, like holding a cracked watermelon together.

About the time of Katie’s first wedding I made a friend who is everything I am not. I met her through my Czech friend Cyril Kinsky. He has twenty-six Christian names, wanted to be a theatre director, and was for many years. Then he fell in love, started a family, and trained for the bar. He is a QC and a virtuoso of marquetry, indeed all forms of DIY. He is also cool, unusual in a DIY-er. Kafka lived to the side of his family’s palace in Prague. His father Alphy smoked more eloquently than any man I’ve seen in my life.

Cyril brought to Cambridge his cousin, Sophie-Caroline Tarnowska. We’ve got an elective affinity. She knows what I think. Her husband Gilles is my son Minoo’s elective affinity. He is a red-headed Protestant left-wing banker of vertiginous musicality. He is so nice you want to take him home. I have loved Sophie-Caroline over thirty years. Recently they took a second honeymoon in Scotland. Gilles reported that the rain was ‘so delicious, so varied, so interesting’.

When Minoo went on his French exchange to the Paris home of this family (all of whom speak better English than I do, so it was pretty silly), he telephoned to say that everything was perfectly all right, actually very homely, for example there was a red-headed grand-mère who lived upstairs with her dog Gavotte and who wore jeans and the oven had fallen out of the wall, ‘just like at home’.

Twice in my life Sophie-Caroline has given me the courage to act as I could not have without her. She has never had to be explicit because she reads my mind.

When I went blind she rang me and I was transfused with a reason to go on. I know that she is devout and she gave me some of it, like a lozenge, or a bit of mint cake on a steep climb, a viaticum, without actually mentioning the name of the Manufacturer, the Almighty, but she was too clever and too kind to be so coarse as to say outright, ‘Do not harm yourself.’

For some of the time, they live in the Gers, in a sublime semi-ruin called Mazères, the ancient archiepiscopal palace of the archbishops of Auch. This house is the great romance of Gilles’s parents, their last shared project, all still very much in the doing. The Angelus tolls daily in the tower. The fields around and the earth and the cows and the farm dogs are the colour of pale bread. In the roof of the palace is a library as long as a church. Minoo lives in this room when he visits. Next to it through a glazed rose window is the music room. It is quite possible to go from the music room into the library and miss Minoo, for all that he is tall, petrified with deep contentment into the room. Down four flights of stone stairs red griffins, faded after centuries, are stencilled in rhythm on the pale curve of the chalky walls. The history of the Cathars and of the Albigensians is legible in one layer after another in this fortress. A corner of a fallen room is blocked up with stone of another shade, from a time long before the already far time that seems to be the closest, yet is already centuries away.

There is an enfilade, falling, snowing, with whitewash, of mirrors laughing thinly into one another, the panelling tactfully bracketing itself around each tall looking-glass. The ceiling asks for chan deliers but incompletion is the keynote. How to describe it? Perhaps if Ely Cathedral grew like an opening stone rose and softly half fell down…?

In this house, at the age of fifty, one night in 2005 I listened out for hornets in my bedroom. I knew I had to change my life before I lost it. A wasp will kill me, but hornets carry more poison, so I’d die sooner. I know, because I was stung by an orange hornet the size of a conker at sea just off Tahiti and that was nearly it for me, before even marrying for the first time. My then fiancé whizzed me by rubber boat into hospital and by the time we arrived my arm was a washing-up glove full of jelly.

Decades on, I waited for hornets, standing with a shoe in my right hand in the hortensia-wallpapered room in the hot Gascon night. The small double bed was occupied by the semicircular body of my then companion. Marcel contemplates the sleeping body of Albertine in like pose, reflecting on the infinitude of traits one human soul may possess.

Such was nowhere near my reflection that night. I knew that to be anything like truthful or kind, I had to get away while there was still time for him to locate another comforter, before I turned on him for nothing worse than his own fulsome nature.

It was nothing anybody said save he himself. It would take Proust’s cumulative genius to show how, feeling himself closest to truth, he most lied. To be with him through time was to see through him like a hoop. So, a profession can take the soul. It was politics that he professed.

In fewer than three months’ time, I shall leave this flat for, as its delicate state attests, it is in need of structural and architectural attention. Its ceilings sag a bit, its draughts are tempestuous, and aspects of its layout, although I have come to love them, are certainly dated. Liv and I get our fizzy drinks from a suavely concealed mirrored wall that you press and it magically opens to reveal a cocktail niche. There is a flip-over serving counter for when the studio was in use for private views in the seventies. There is a door into the studio that obviates the necessity of entering the artist’s private apartment, a system put in place for Sargent. The colours, that will of necessity have to go, are kind to pictures, ranging from every kind of dove grey through to lichenous greens and, in my bedroom, a colour that combines pink, blue, brown, grey, white and black and yet is very light; the colour of the gill of the smallest, freshest, field mushroom. The sitting room, that we call Henry James, might be any colour. It is the colour of memory, a tactful background, a recessive, becoming, dark but festive, shade, making everything hung upon it look better.

Five or so years before his death, the owner of this flat sustained a stroke that made movement difficult, although it did not stop him painting. In order to help him remain independent, banisters and grabs were installed exactly as though it had been a ship. They save me from sinking.

I could have done with more of those grabs, on a metaphysical level, when I was at Cambridge. I did not know that there lay within me a thirst nothing could quench that would nearly kill me. There were signs, but they were illegible to me and my friends at the time.

My room at Girton was called F6; it took some ascending to. I was next to a popular girl whose parents visited most weekends bringing lox and bagels. I was very grateful one Sunday when the mother of this family gave me a bagel, stuffed full. Some kind of fear set in. I did not understand how to get out of one’s room except to go to the college library or for meals in hall. I knew that when women were first up at university they joined one another for intense conversation over mugs of hot chocolate. I had two mugs, so that was a start. Further research revealed a row of three baths, each in its cubicle and each the size of a lifeboat, so I spent a good deal of my first year at Girton just sitting in the bath reading and getting wrinkly. I was an unreliable and irresponsible student, having come straight from school where, during the last term that Katie and Rosa were there, I had worked as a housemaid and kitchen maid, because I had got into Cambridge before my A levels, didn’t want to be separated from them and needed to earn money. It was interesting to see the modification of girls’ behaviour towards me as I changed from senior to skivvy. Mrs Rock, the house cook, was kind to this unhelpful pair of hands and gave me jobs she knew I could do like emptying the commercial dishwasher, grating fifteen pounds of cheese, or slicing ox liver and onions for fifty-six people with a knife whose steel was whippy, sharp and thin as a line.

The school train started at Waterloo and ended at Sherborne. For some happy reason, one summer day when we were in our A-level year, it dawdled at Basingstoke. We were told that we might go and purchase refreshments at the station buffet. We were not yet changed into our school uniform, and no one in their right mind would want to challenge Katie’s raised eyebrow. We purchased two pork pies and two miniatures of brandy. Brandy is rage and turmoil to me, gin the taste of isolation.

Otherwise strong drink hardly made its appearance at Sherborne, though there was a rebarbative cocktail offered by the headmistress to those girls considered made of the right stuff to meet visiting preachers such as Sir Robert Birley, formerly headmaster of Charterhouse and Eton. Katie and I were chosen for this privilege and liked him a lot. Neither of us felt the same about Dame Diana’s refreshing sherry, tomato and orange juice cocktail that was the speciality at White Lodge, the headmistress’s house.

In the first weeks at Girton, should someone have asked me what was wrong, I would have replied that I was simultaneously anxious and bored. I seemed frozen to the spot. I couldn’t leave my room. In my room was a bottle of sherry. Everyone knew that undergraduates offered one another small glasses of sherry. I drank the bottle on my own and went to sleep. I imagine that this sleep will have been the first blackout of my life, and that having glimpsed this option, my brain’s biochemistry was on the very tentative lookout for more.

There was a bus that took Girtonians into town for lectures and seminars. I ended up sleeping on the floors of my patient friends, Anthony Appiah the most patient of all, playing me his records of Marlene and Mahler and Noël Coward and allowing me to cramp his love life.

Of course there were some friends from school. Edward Stigant, descendant of the Archbishop Stigand on the Bayeux Tapestry, was reading History at Christ’s under Professor Jack Plumb. Edward looked like a very naughty Russian girl. He had the profile and eyelashes of a Borzoi and was short, lissom and bendy. His gift with languages was prodigious. When we did our examinations for Oxford and/or Cambridge, which were in those days separate from A levels, there was a translation paper from which you had to choose two longish passages from among a dozen or so languages to translate into English. Edward had done them all, with time to spare, and waltzed off with a scholarship. This took courage. His older brother had earlier achieved distinction at the same college and taken his own life while still at university.

Edward did not live very much longer than that brother, but oh the delightful nuisance he caused in his life. He was completely kind and, of course, when we first met at the school classics club, ‘The Interpretes’, which was a decorous means of meeting boys, I lapped him up. He was having an affair with a Turkish air stewardess at the time. This strange reversion to what might be thought of as deviancy in the context of someone quite so camp, also struck him during the week of our Finals, when he fell head over heels in love with a magnificent girl, and sent her a dozen red roses every single day. They both emerged with congratulatory firsts.

I’m astonished that I have any friends from Cambridge. I was a dilatory worker, a shocking shirker of essays and supervisions, and I did not understand that it was perfectly possible to say no at any stage of the transaction should you be invited out by a member of the opposite sex. I had a powerfully developed sense of my own repulsive ness that cannot have been helped by the fashion for platform shoes that coincided with these years. Thus, when I did leave F6, I was six and a half feet high and, in some senses, quite unstable. There were three dons at Girton whom I feared and respected, though they might not have guessed it: Jill Mann for Chaucer, who spotted me at once for a coaster; Gillian Beer, who has, despite it all, become a friend; and Lady Radzinowicz, who, with her dachsund Pretzel, taught me Milton and Spenser. I was so nervous about leaving F6 and actually getting on to the missile-launcher bus for central Cambridge, that I attended relatively few lectures, though I developed a fondness for Professor J.A.W. Bennett who must have been about twelve hundred years old by then. It was also compulsory, for reasons of cool as well as literary curiosity, to attend the lectures of the poet J.H. Prynne. I adored watching him take words to bits.