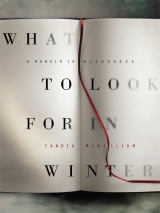

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

We agree that green and white, and blue and purple, if she can find any, should form the mass of flowers that she will leave at the church for the ladies of the family bereaved to set about it as they wish. Bluebells are the right colour, we decide, but they are not sufficiently respectful. They are the juicy flowers of childhood, abundant, scented, profligate and wild. They do not look like trouble taken when they are massed, and they are at their massed best when left alone to smoke up a wood with their heavy blue.

There is a jar of bluebells on my dressing table, put there by Katie’s son and his Iranian fiancée. He is a boy and doesn’t read the language of flowers. She, being Persian, like my younger son and his father, well understands some languages beyond the spoken, of which she has English, Arabic and a little Farsi. She knows the good luck in a mango, the transportable nourishment in a coconut, the relation of sugar to good words.

The men on Colonsay leave a funeral halfway through for the committal of the body to the earth. A dram of whisky for each man is passed around, and a bit of cheese.

The women remain in the kirk and weep.

Chapter 3: Milk Money

A book containing some of Chekhov’s plays arrived here on the boat last night. It came from a dealer in New South Wales. I hadn’t seen when I was buying it online that it was on the other side of the world. I was interested by the translation and the edition. Reassuringly, the edition at least is a properly Chekhovian disappointment. How can I have missed that the reason for the rock-bottom price was that the publisher is something called The Franklin Library, at the Franklin Center, Pennsylvania? The translation is by Elisaveta Fen, and copyrighted to her in 1951 and 1954. The edition is copyrighted to the Franklin Mint Corporation.

Do you remember the Franklin Mint? Do they still exist? I think that I once actually did write advertising copy for them, or have I invented that? Certainly I have not invented that they specialised in ‘Collectables’, ranging from themed thimbles with an ornamental display unit to show them off to best advantage, and poseable figurines of the late Diana Spencer in occasionwear with fully styleable ‘natural’ hair. In the early days of Sunday colour supplements, I enjoyed playing with the sorts of advertisement the slippy magazines carried on their back page. It was only in these ads that I ever did read the actual word ‘Skivertex’.

My father and I would ask one another, in a special advertising voice, ‘Have you ever longed to caress a book?’ This was the headline of a certain ad that offered classics of world literature for now and for all time in luxurious gold-tooled Skiblon, duchess green or cardinal red. I was absorbed by parallel idioms and by what you could do with words, and how words caught you out and showed you up, tickled you and took you in or left you out.

This not merely indoor but interior habit was not interpretable as much other than showing-off and time-wasting by my poor stepmother, who preferred her jokes less silly and whose ratio of meaning to word is a clear one-to-one. She was right to be suspicious of me. She thought I was a liar but actually I was something less direct: an ambiguity obsessive.

She was right that I was having a stab at making a shared world with my father, in the language we both spoke, but, to his matrimonial credit, he soon ceased to meet me on those borders and one sort of atmosphere lifted. While I love Greek and Latin, he never thought me much good at them and couldn’t understand why I had not a grip on Greek accents. In the ‘girls’ Greek’ taught at that time, accents were not included.

My stepmother to this day speaks a pure English that delighted him. English is a corrupt old tongue but in her words, spoken and written, it says what it means like a tread of precise hemming settling a margin of cloth. I listen to her talk with pleasure, and, freed from hot adolescence and respectful of her long widowhood, I realise that her speech must have been to him both a relief from his own subtlety and a line to clarity at an obscure time.

There is a line of thought that maintains that all writers of fiction are liars because they make things up. This coincides frequently with the other line of thought, which also thinks itself interestingly robust, that it is women who read fiction. And, moreover, that they do so to escape.

Proper fiction tells the truth by a means that, far from producing pain as untruth does, gives pleasure; this doesn’t mean that it fails to reproduce or convey pain. The transformative element is not lies but art. Human truth is caught in translation, such that we may briefly be as close to not being ourselves while we read as we shall ever be. It’s not a promise, but there is always the promise of a promise.

As for women reading escapist fiction, why would women wish to escape, if not from a nonsense world of material fact and of drudgery that is there, often, to free men?

And here I am in the autumn of my days, privileged at last to caress a book, gold-tooled for my handling pleasure, though the hide-type spine is not duchess green nor cardinal red but buckram brown.

Still, the book, whatever the cover, held its transmissible voltage. I am, of course, in a flat that has been made from the nursery bedrooms of a beloved old house in which a number of generations have lived. I’ve never known a time when things were at all fat on the estate. Twice at least in my time of being almost in the family it has been put on the market. Most of the children’s lives are formed by the place. William, who was an art dealer, makes his living from chopping down trees, carrying coal and emptying dustbins. The sound of an axe is rarely far off from the house. He walks around with an axe as easily as with a book.

It is May. In the walled garden lies a cold dew between the fruit trees.

I held open my eyes on this chilly early morning in May where outside the many greens under the cold wind are shivery with blossom and read the opening of The Cherry Orchard:

ACT ONE

A room, which used to be the children’s bedroom and is still referred to as the nursery. There are several doors: one of them leads into Anya’s room. It is early morning: the sun is just coming up. The windows of the room are shut, but through them the cherry trees can be seen in blossom. It is May, but in the orchard there is morning frost.

The last play I saw in the company of my mother was The Cherry Orchard. I had forgotten this till now, or so I think. I must I suppose have remembered it every time I’ve read the play since then, or when it’s been mentioned. I’ve not seen it again, which is a bit peculiar. At that first, that only, visit, I was painfully bored until the end, when I couldn’t bear it to stop in the way it did. Perhaps that’s what they mean when they say Chekhov is like life? Unbearably boring, then you don’t want it over with. Or, please, not like that. Boring isn’t the word, is it? The word is…like life.

Not ‘lifelike’. Which is for inanimate things that imitate life. The plays of Chekhov breathe. They summon life. They are…like life.

After she died the first play I was taken to was the Alcestis of Euripides. It was in English. Alcestis, Queen of Thessaly, vows to die in the place of her king, Admetus. Admetus, aghast with grief, nevertheless proves a noble and generous host to the man-god Heracles when he visits. In acknowledgement of this, Heracles descends to Hades, wrestles Death, and returns with a veiled woman whom the King will entertain in his halls only as a courtesy to his guest. Heracles persuades Admetus entirely against his will and protesting to lead the woman to his own chambers – and the woman turns out to be his dead queen, whose absence had made the palace a grave, restored to him.

Perhaps it was a consolation. Given my parents’ milieu it may even have been a consolation that had been dreamed up. For which I thank any of them who survive, who may read this. I know I enjoyed it though Queen Alcestis herself was too short to convince in her part as my mother.

Art did some of its work then. I thought of this theatre outing with shame when my younger son and I went to Britten’s Rape of Lucretia together. Better at seeing into life at twelve than I at any age, he sat holding my hand in the airy Maltings at Snape in Suffolk. We were there in the company of Mark Fisher. It does not do to think that we will not pass on to those we love pain that we have ourselves sustained. So many kinds of blindness are involved in love that can in its turn bedizen us with sugared illusions.

We watched Tarquin sucking up to Lucretia, making his case in frontal fashion, warrior without and weasel not far within, and we watched her piteous shame. My father’s deep attachment to the work of Britten and his taste for the composer’s summoning of pity and fear without grandiosity has come straight down to me and Minoo.

It was as much the fault of the woman’s vanity, the music made it plain. Yet Minoo never let my hand go. He is a realist and a natural writer who saw it all before I did, and waited, a seasoned reader of Greek, accents and all, for the consequences of the actions and inactions that might have made his life unrecognisable to him, had he not decided that, being life, it was to be royally respected and stuffed with jokes. And taken at an angle when it was sore.

It is my lunch hour in my nursery-study on the Isle of Colonsay. The reason why I cannot hear an axe is that William is in church for the funeral. I decided that I should not go because although I knew the dead man I look so odd at the moment that I might be a distraction. Then I wondered if that was not vain. Where is the proper place to be? In church, I suspect, now the funeral is under way. What does it matter that I bore myself explaining why my face is screwed up and I am twice the size I was as a girl? No one is looking and probably the ideal place to be to avoid explanation is here, where all is known anyway. You don’t keep a secret long on an island with 120 souls.

I allow myself to listen to the radio during my lunch hour. I switched it on and there came the sigh and rush sound of an amplified seashell. ‘Ah,’ I thought, ‘that’s interference. The reception is bad here.’

It wasn’t. It was applause. A different kind of reception. It can be hard to tell what’s what in the world of sounds as well as in the world of seeing.

I had a short blast of sight earlier and looked out on the pair of tall cedars I seem always to have known. There are in fact three of them.

After my time in hospital that was in order to observe and catch me should I have another fit, I was allowed home. None of us knew what had happened. During the preceding two years, several highly qualified neurologists and neurosurgeons had taken a squint at my brain and its nervous system. A neuropsychiatrist of penetrating if iterative intelligence had reminded me weekly in a slow crisp intelligent manner of the inception and progress of my complaint, at the price of a…I can’t actually think of anything that costs as much as private medicine at those reaches of obscurity. And there was no one in the National Health, apparently, who could address my brain’s particular problem of function after the failure of botulinum toxin injections.

I have thought of a measure of cost. During my years of reclusion and then of blindness, I reverted to stereotype. Female novelists are caricatured as troubled, often overweight beings accompanied by at least one cat. As readers may remember, I had two, by the time of the fit, a Blue Russian cat called Rita and a creamy soft British cat with lilac edges and a butch glare, whose name was Ormiston, a name given to male McWilliams for hundreds of years.

If you don’t like cats, skip this paragraph. Rita came to us when our first Russian cat Sigismond was run over. She is his sister. Her first owners had not been able to care for her and her second owners became allergic. She is nervy, possessive, controlling, man-mad and clever, a bossy animal devoted to Parmesan and small warm places. Her eyes are green with a turquoise depth and she has the incomparable limbs and head of a Russian. Her middle is soft. Ormiston’s breed is meant neither to be fluffy nor intelligent. In both regards he failed, if it is a failure to be fluffy and clever. He showed from a kitten, when he was the size of a meringue with whipped cream, preposterous bravery, devotion, ball skills and single-mindedness. Prawns and human love have been his areas of study. Between the cats lay the vexed questions of all shared private lives, power and influence. Our family divided just about fairly around the cats, my older son keeping a good balance by liking neither. These animals, who comforted my nights and conversed with me through the days, who knew my goings out and my comings in, who petted me and fed my need for contact, who were the differences between the often sluggish days, cost £350 each. It is a great deal of money, but one visit to the doctor who recapitulated to me each week my illness’s symptoms and progress was two cats per hour or every part thereof.

Not one cat, or part of a cat for a part of an hour, two full cats.

Not that sight isn’t priceless, but I was being prescribed drugs. These drugs came to about two cats a month. I saw, or attended, in addition, during that time, at least two other doctors per week, at a combined cost of two cats. The cats added up.

By the time of my fit, I was ingesting multiple high doses of venlafaxine, mirtazapine, levetiracetam, and had been through exceedingly high doses of citalopram and lamotrigine. Zopiclone had wended its powerfully stupefying way among them like a thug whom you fancy. I’d abandoned beta-blockers because they scared me. I preferred the panic they were meant to stop to the nasty medicinal panic they created.

The drugs bothered the children. A number of these drugs are powerful antidepressants. When first I was blind, no one suggested that I was depressed. I was not happy, but my circumstances had been peculiar for years, and now I seemed to have gone blind. Happi ness of any marked sort at such a time might have been surprising. After I was first put on these drugs, with the primary purpose always being that they might in sufficient doses cause my brain to release my closed eyes, it was opined that I was indeed by now depressed. I was still sad, maybe sadder, but all my own observation of depressed people, and I have had a good deal of it, told me that I wasn’t depressed as they had been. I was, since becoming sober, never unable to create a pretext to enter the day. I could spur myself yet.

However, the insistence was by then that, having taken so many antidepressants, I was depressed. I was taking sufficient antidepressants to cheer up a cow by the time I fell down thwack in a grand mal fit in that shaded summer last year, just after speaking my first book for more than ten years.

After the fit, the children arranged a rota. They, or their friends, babysat me for a time, day and night. The cats and I loved it, when we were conscious. I couldn’t any longer recognise myself, even from within.

I’d grown used to my swollen and unfamiliar body, but now my mind was loosening and, it seemed, hardening too. I was returned to the same thoughts with a repetitiveness that grew tighter and tighter. I couldn’t challenge my own poisonous logic as ably as I once had. I had aged suddenly, become a dead weight on those I cared for, a bore, ugly, terrified and alone; and I deserved it.

Perhaps the antidepressants had at last, as one doctor hazarded, summoned their customary foe. During these sweaty nights I longed for the unabridged In Search of Lost Time but listened over twenty-five times to the Naxos abridged version, read by Neville Jason. I have now, by May 2009, heard it thirty-seven times. At the end of the last uninterrupted run, I turned to War and Peace, unabridged this time. It too is read by Neville Jason. Not one of the voices he does for each character in either book is the same as any other. I cannot sufficiently thank this stupendous actor and enthusiast. I hope he already has the Légion d’honneur. By abandoning myself one at a time to the sentences of Proust, albeit translated, I saw off zopiclone, even if I did not see off nightmares. The cats came and went happily in the garden of the borrowed flat. Rita lay on the hot terrace under the olive tree and Ormy fuzzed around under the spilling hostas and catmint playing ping-pong with bumblebees. From time to time he tried to kiss Rita, holding her precise head in his feathery paws, but she cuffed him. Early in the mornings, between five and five-thirty, he would come to me. The drugs made me sweat heavily. Sometimes it was tears, sometimes it was sweat, but my cat Ormiston made as though to pat my face dry with his front paws. He held his claws quite in, and laid his pads on my eyes.

In July the builders were to arrive. They wanted to work over the whole place. They started the day prompt at six-thirty. They were drilling out a whole new basement room. Every bit of rubbish, masonry or earth or mortar, plaster or lath, had to be carried back through the building in sacks and into a lorry for deposit at a yard. Hundreds of designated sacks were filled and hoisted daily. One can only hope that the fate of these sacks of building materials was something less sad than to be tipped into the sea between islands as a metaphor for loss, like those daily sackfuls of cement on Colonsay.

I moved into the flat on the floor above; it was less dramatic and atmospheric than Sargent’s former studio, but more practical too for a blind woman prone to fits. I was very confused. My friend Nicky found me weeping outside Tesco because I couldn’t find the hospital where I was due for an MRI scan. She cancelled her whole day and took me, holding on to me and steering me and taking me for the scan, then taking me home. I could have done nothing without her. I could not put one thought in front of the other. Not. One. Thought.

In May, in Colonsay, the weather is prevailing. Rain is pouring through and down all the guttering and downpipes, what in Scotland are called the rones, and hail is tittering down the chimneys and on to the sills. The air is full of long brushes of rain, the wind whisking them. My radio, responsive to something electric in the weather, perhaps a storm to come, has become impossible to turn off. It’s desperate to tell me something. I’ve taken out its batteries: that’ll settle its hash.

There must have been times when my family, most particularly Fram, must have wanted to do something like that to me, just shut me up, turning me over, sliding open the panel and slotting out whatever it is that keeps me transmitting. At the worst times I have only one frequency, that of guilt and shame. Self-pity is the one I fear. It’s what I’m worried would be on default, on my pilot light.

This silence after the rain’s battering is delicious. Though it isn’t complete. Don’t say the radio can broadcast without power. Don’t say the radio is in my head.

I moved to the upstairs flat in London, and settled there but for one thing. Two things. Rita and Ormiston. I realised that it had to be done. It was a smaller flat, with no outdoors. I was blind and might fall down unconscious in a fit, and then who would care for them? Rita went to be with an artist’s widow. Ormy went to be where he was always ecstatic, with our friends Leander and Rachel in Oxford. They reported on him constantly and in short order he had become Rachel’s slave, which in cat terms is master. Leander said that he chased butterflies but released them. I suppose he never caught them. He was the indulged new boy in a house with four other cats. At first uppish, he became the lieutenant of their top cat Elvis. He gardened and grew fat on tuna and prawns. To the children in their street, he was known as Warburton, a name as pleasingly Britishly pompous as his own. He got a bad scratch on one bulbous blue eyeball and had to wear a bonnet and have twice daily antibiotic shots over the summer. Rachel made their sitting room his sickroom and gave him love all day. She was looking for work at the time and awaiting the results of interviews. The artist’s widow has not said anything about Rita, herself a companionate but discreet cat never much given to getting in touch.

July dwindled into August, which has all his life been the time when Minoo and I go to the Edinburgh International Book Festival, and then, most likely, over to Colonsay.

I had a plan too for our stay in Edinburgh. I was hoping to visit the shaman who had helped the friend of a friend, as she understood, to see off grave illness from the very heart of her family.

A shaman?

Why not? I had by this point seen seven professors of neurology, one neuropsychiatrist, two consultant neurologists, two cognitive therapists, four ophthalmologists, one psychoanalyst, one counsellor, two general practitioners, a cranial osteopath and a beautiful octogenarian acupuncture-practising ex-nun named Oonagh Shanley Toffolo, who had modelled for Issey Miyake and to whom I was recommended by the owner of a clothes shop who saw me blindly patting her lurchers under the counter. Oonagh was very good. She was a great reader of Thomas Merton and was as certain of heaven as of the ground beneath her slender feet.

I am not on the attack against conventional medicine. I just think that no one knows much about the relation of mind to body, while, it is to be hoped, learning more constantly about the relation of brain to body, though even that science is in its infancy. I have wondered, for example, whether my compromised dopamine system (which is what alcoholics have; we retrain our poor pleasure centres into thinking that a drink is what they want because once, just once, and once upon a time, it felt good) has not some relation to the closure of my sight. I do not know, and I am, or thought I was, resistant to barmy science.

I am aware that the dopamine theory could just as well be the punishment theory in modern dress. I cannot bear to think that maybe the enormous pleasure that has for me been in looking has to be taken from me precisely because it was a pleasure and that for me all pleasure is bad, being analogous to alcohol. Can that be so? Or has some Calvinism crept in there?

I am pretty sure that if I had ever understood – and practised – relaxation, and in that I would include dancing and some kinds of exercise as well as I understand willpower and self-punishment, I wouldn’t be in this tight spot.

I am fairly certain too that an operation is a crude and mechanistic approach to something that maybe I should have tried to charm down out of the tree of my nerves and brain, a bad black snake I might really have induced to let go its grip, with talk and ease and music. Instead, full of fear, and keen to show those I love I have the will to fight, I have done the thing that Fram was the second person to tell me that I will insist on doing, which is to go out into the dark alone with a knife, and cast about me till I am bloody and on my own. Fram is far from the only person I love who is resistant to the idea of this operation.

The first person who told me that I do this blind casting about was me. But I don’t listen to her. Or not when she talks sense.

Or I hadn’t till recently, and am attempting to now.

We set off for Edinburgh, where Minoo and I have been the consistently happiest over the years of internal exile, but not before I had had a terrible unseemly fight with Fram and Claudia.

It started with two pints of semi-skimmed milk and two one-pound coins. I cannot write about it while the rain outside is falling. If I feel tearful when there is rain, the rain allows me to cry with its tears. I have learned this through a lifetime of living in a rainy country and seldom actually crying, though sometimes feeling that I will burst if I do not, by the use of one of my bluntest tools from the kit of self-damage, unnecessary control. I boil my tears dry on the nasty internal burner of my sense of injustice, and my hot stone of loneliness.

Jealousy pains more than bare bones through skin. That’s not a figure of speech. I’ve had both in this last year and there isn’t a comparison. Jealousy is greener than those old sharp white bones I saw, though they were my own and sticking out sharp and splintered through my own flesh and skin.

But that’s to come.

I am daily working on its cure, the slaking of that thirsty rootless jealousy. If love is blind, jealousy is sharp of sight, even in the blind. Maybe it seethes more in the blind, who create evidence where it cannot be seen?

I will save any account of that row till the sky is empty. It was my fault. By the pitchy light of my jealous nature I will perhaps see the sequence of my, always congruent, mistakes. I always slope off and never ask for help. I think I can mend myself on my own by thinking and instead I make the same mistake. I do not see it as being the same mistake in my own life because I treat myself with less care than I would treat a character in a book I was either reading or writing. I always think, however extreme the circumstances, ‘This doesn’t matter. The only person who is being hurt is me.’

This idiotic yet evidently lifelong feeling for some reason does not allow itself to be supplanted by my expressed and fully conscious certainty that, however secret we are to one another, we are also connected in more ways than we can know.

I think the word for it is dissociation, and I wouldn’t recommend it to an atom. Especially not to an atom, since the consequence might be annihilation.

Minoo and I set off for Edinburgh. My Edinburgh friend Amanda had made an appointment with the shaman, in a suburb of the city called Portobello, a suburb that is something of a hydro, which is the Scotticism for spa, that is a fancy place you go for sea-bathing and the taking of the waters.

Plural water! And I’m that big a drinker!

(I recall participating in a blind water-tasting with the son of Hugh MacDiarmid, Michael Grieve, and his wife, for the Glasgow Herald, in the house of two Highland friends. Apollinaris and Perrier were too strong. Later, we watered the water down.)

Amanda, who, like all my friends who properly like me, likes Claudia, said, ‘You’ve to guess the shaman’s name. It’s auspicious. It’s what everyone’s called, Claude.’

The shaman’s name was Claudia.

During that time when the fit held the summer thick and dim to me and I felt ever more cut off and adrift, I didn’t say so until things became so desperate that I burned with disgust and anger at myself. The only person to whom I dared show it is the person for whom, with the children, I want to be best, as though I hadn’t yet understood that he knows me at my worst.

All the things I miss doing for someone, the things that I thought were the accumulating point of me, cooking, cleaning, tidying, arranging, thinking together, sharing silence and words as Pierre and Natasha do at the end of War and Peace, all the setting forth in the vessel of home, I blew into the air with one neglected cinder of resentment allowed to smoulder over years because I accepted to be tidied away. Was that the pilot light? Resentment?

I didn’t accept it, only, to be tidied away. I folded myself up like an unwanted sail and locked the sail-bin door from the inside, not having forgotten to make sure I was dry with exhaustion yet drenched with alcohol to the point of double flammability.

The rain has gone and I shall rush at the story of the row and the milk and the money, which is about jealousy and left-outness.

So Fram and Claudia visited me one evening in the upstairs flat in London. They were going on, out to dinner, or the theatre. I was overexcited and had saved up a selection of thoughts, of notes and queries. Thus the lonely blight the contact they do have. Punctuality exercises me. It is part of my tense need to be prepared and hospitable. It has always been my failing and it is made worse by not seeing because I have to try to make things, and myself, look OK. Or I think I do. After the time that was due to be crowned by company has passed away, a dismantling takes place as though an actor has been taken ill before the performance can be begun.

Claudia rang from a supermarket. I am afraid that I can remember that it was Waitrose and not Tesco. Waitrose is more lavish and metropolitan than Tesco. Such is the ugly smallness of jealousy.

She was ringing to say, ‘We’re in Waitrose. Can we get you anything?’ I replied, ‘I’d like two pints of semi-skimmed milk please, and don’t worry, I will pay you back.’

As cheap as that. A world of love, flung aside from jealousy because it is one who has fallen short of it. I knew I was old and past it all then and that Fram and Claudia were like my social workers, fitting in a cup of tea with the old bitch who can’t get out before they returned to their real world of intimacy, the first-person plural, litres not smaller units, love, the theatre, seeing things…and Waitrose.

Actually I can’t, yet, bear to go on. Jealousy is hard to abide in the feeling, the telling, the reading. It is witness to our worst selves. It is mad and hungry and it tells us lies. Which to our shame, we half want to hear.

I have for the moment to hold the frame there. I typed ‘Fram’ in the middle of that word ‘frame’. There is nowhere jealousy doesn’t reach, nothing it doesn’t sour. It tears the kindly milk.

This is the frame, held. They entered the flat. Claudia had on a new coat. I couldn’t see it properly of course, but it was embroidered with pink and green flowers. She is of normal size. I have always been tall for a woman and am now fat. She held the milk out to me. I held out two pounds in return for the milk.

I could feel Fram’s anger as close as my own bile.