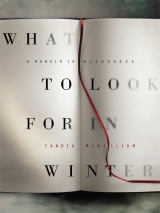

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

This last refusal of distraction is entirely true to the line my father in his life took and the lines he made and the lines he drew.

Looking, now, at the high window and the plain grey of the walls, though I see very little clearly, I do see a composition that is timeless: a young woman of lovely form at work at a table on which rest some vessels and a jar of flowers. If I scowl and make horrible faces, I can see what I already know, that the young woman is Liv, that the vessels are mugs, glasses and bottles of scent and that the flowers are what must be gathered in their season and cut and cut again, sweet peas.

All that is required is a frame, and it is that which I’m attempting to construct with these words. By opening my mouth very wide, as though I’m screaming, but without sound, I can open my eyes in sympathy and read from The Soul of the Eye what it is that Poussin has to say about framing his picture The Israelites Gathering Manna:

I beg of you, if you like it, to provide it with a small frame; it needs one so that, in considering it in all its parts, the eyesight may remain concentrated, and not distracted beyond the limits of the picture by receiving impressions of objects which, seen pell-mell with the painted objects, confuse the light.

It would be very suitable if the said frame were gilded quite simply with dull gold, as it blends very softly with the colours without disturbing them.

It is very difficult indeed to prevent the memory from confusing the light; as for the frame, I am attempting to gild it not at all save where it is of its nature golden.

Fram says that he never reads the childhood part of any biography, since childhoods bore him. He also used to say to me that one of my benefits as a wife was that I had no family, which is, strictly, very nearly true.

But I did have and do have the long, and for the most part by definition insular, since it took place and takes place on an island, family romance with the six Howard children and their parents, their stepmother, their beastly dogs, their fantastically frightful paternal grandmother, who on first sighting me enquired, ‘Who is the common girl in the corner?’ and who ended up by making revolting but much-loved bargello cushions for my first wedding present, embroidered with the coat of arms of my husband, and to whose wheelchair we tied fifty pink and fifty white balloons on the christening of my first son, so that the tiny fierce termagant was lifted up in her chair to the summer sky. She once again became, as she must have been in a hundred ballrooms when she was Di Loder, one of the identical Loder twins Diana and Victoria, who were on nonspeakers for half a century, a red-haired beauty afloat in white and pink, the cynosure of all eyes.

In order to make the crossing to the island of Colonsay it is necessary to end this chapter here.

LENS II: Chapter 4

Liv, who is twenty-two, has just asked me, at the start of our working day together, whether it would be better to be stone-blind than to be in this flickering and changeable state. As it happens, I have been up working for several hours and am therefore very close to stone-blind, but still it is inflected and there are colours within my eyelids. I seem to remember from accounts written by ‘properly’ blind authors like Ved Mehta and Stephen Kuusisto, that ‘real’ blindness can also be continually modifying within its veils and infinite shadings of black, or, more often, white. Of course, it depends on the kind of blind you are.

Liv’s question is an intelligent one. Perhaps it is the question; I’m certainly honoured she asked it, since it demonstrates a levelness of attitude to her employer and the peculiar situation she finds herself in with that employer, who is me. She made the point that her mother is averse to change, but that she, Liv, were she to be visited, heaven forbid, by such an affliction, would attempt to extract from it all the good that could be.

I recognise myself when Liv speaks of someone averse to change, but my life has been so zigzagged in its shape and so full of abrupt change, much of it caused by me, that I am unsure what not-changing – one might call it security – feels like. Perhaps this blindness is just another, negative, attempt by my mind to deal itself some security, by reduplicating the loneliness in which I found myself with that loneliness’s thickening through blindness. This remains to be seen.

I made a short, parodically adult, not totally convincing speech to Liv about acceptance of whatever comes one’s way, and the necessity to make an honest attempt at turning it to the good. I also told her the plain truth, which my friend Julian Barnes regards as tosh, that I feel as though, if I’m hurt, others whom I love will not be. The scapegoat theory, he calls it, and I thought of the dreadful Holman Hunt painting.

Still, dum spiro, spero, otherwise why would I be visiting so many doctors, at least three of whom seem resistant to the concept of my registering as blind, even with the promise of a guide dog, parking concessions, and other benefits that come with such officially recognised status?

My grey cat Rita has occupied the chair I sit in to Liv’s right. Fram has just rung to say that he is going with Minoo and Claudia to stay with mutual friends in Yorkshire over the bank holiday weekend and that he had a happy birthday yesterday. Sometimes I cannot be sure when I’m going to wake up and realise that it’s all been a dreadful dream and that I am well again and not alone and can sit in my own chair and read a book.

I say to myself, ‘Worse things happen at sea.’ After all, none of what is sad is happening to anyone but me. I must take Fram’s advice and detach, detach, take sannyasa insofar as a middle-aged Episcopalian can. I’m not made of the material that makes a modish new age Hindu or Buddhist. Fram is a Zoroastrian, a faith that accepts no converts, although it is so very practical a religion and way of life. But all that is for later.

If Liv hadn’t asked me her plain courageous question, we would have begun this chapter with a meditation on the place of magazines, especially fashion magazines, in contemporary life. Let’s get it over with and then we can set about the serious business of addressing the ferry that takes you over to the island of Colonsay.

We were not allowed to read magazines at boarding school. This heightened their value dramatically. We had in our house at school at least one accredited beauty and I think it was she who smuggled in a copy of Vogue. Her name is so apposite for a beauty that let me put it in; she is the granddaughter of Daphne du Maurier and her name is Marie-Thérèse de Zulueta. Although we were not allowed to watch on television the funeral of the late King Edward VIII, then Duke of Windsor, because he had been an adulterer, Marie-Thérèse was allowed to watch the film of The Birds, because her grandmother wrote it. She was allowed to sit up with our matron, Mrs Fraser, and watch all that avian horror on the little brown box.

Marie-Thérèse had hair thick as a squaw’s and the colour of corn that reached her waist. She had an olive green velvet hair ribbon, bendy eyelashes, a glamorous stepfather and a glamorous father and was like me addicted to Nestlé condensed milk sucked from the tube; that bears some looking into. Boys fell on sight of her like ninepins. This in the days when we had to cross the road if we saw a group of boys from the Boys’ School approaching. Men fell too for her mother. They both had faces of the ideal proportion, clear brow, low large eyes, perfect mouth, the features disposing themselves in baby-like proportion in the lower two-thirds of the face.

Edward Heath was in power. Electricity was rationed and for several evenings a week we were without it. This copy of Vogue fell into my hands. On page seventy-five, an announcement was made about Vogue’s annual Talent Contest. I’ve always entered competitions, the motive mostly publication or cash. In this case, it is fortunate that my habit was so undiscriminating, or I am sure that I would have been expelled for having entered this one, let alone running away from school for the day without telling anyone to have lunch sitting between Lord Snowdon and Marina Warner (who had on yellow satin hot-pants with a heart-shaped bib).

The competition rules stipulated that all entries be typed, double spaced; I had no typewriter. I wrote and drew my entry after the long school day by candlelight (absolutely forbidden for obvious safety reasons) with fountain pen and (contraband) make-up for colouring in my drawings. There were several parts to the competition, the only compulsory part being to write one’s autobiography. I had no very long life to write about, being fifteen, and caused great offence to my family on all sides by describing my poor stepmother, fatuously, as resembling a ‘beautiful milkmaid’. I also designed a Summer Collection around a moth motif and selected whom, alive or dead, I would ask to dinner. I can remember only Elizabeth I and Evelyn Waugh. I’d never made dinner or held a party.

There were in those days telegrams and I returned to Aldhelmsted East, after that disorientating day at Vogue House in London, to find that I had won by unanimous vote the Vogue Talent Contest for 1970. Thank God, and I mean thank God, the headmistress had also received the news on that very day that I had won a national essay prize sponsored by the Sykes Bequest, the topic to be selected by the entrant, anything at all as long as it was to do with Missionary Work. I had written a long, very boring, wholly invented, essay about smuggling Bibles. It was fictitious but full of detail; never did I feel so grateful for it as when Dame Diana Reader-Harris announced the double news concerning me at prayers the next day; that I had won five pounds in a national essay competition dedicated to Missionary Work and that I had also won a prize given by a magazine called Vogue.

The Vogue prize was a huge sum of money, fifty pounds, but the real prize of that contest remains to this day an astonishing one; every winner of the Vogue Talent Contest is awarded the chance of working on the magazine. What in my case this achieved will be seen; for most people it is an incomparable entry into an impenetrable world and a golden opportunity. I fear that for me it was a reason not to become an academic or a teacher and then it led to many of the things that are worst about, and worst for, me. But that comes later. All I will say for the moment is that magazines are, without a shadow of a doubt, addictive.

‘The Earth is the Lord’s, and all that it contains

Excepting the Western Isles, for they are David MacBrayne’s.’

Anyone who has been to the islands of Scotland will recognise the truth of this. MacBrayne’s run the ferries that are quite literally a lifeline to the islands. Every sheep, every jar of Marmite, every tank of petrol, every cornflake that you consume on an island in the Inner or Outer Hebrides will have been brought there by MacBrayne’s and will consequently have a surcharge that is referred to as ‘the fright’; that is, the freight. There are perhaps only two travellers over the last century of whom I’ve heard, who have travelled between the islands – save of course for those on private transport, yachts or planes and such – under their own steam and these two valiant travellers are a bull who swam from Barra to Vatersay and Hercules the grizzly bear, star of the Sugar Puffs advertisement, who set out on his own after a tiring afternoon’s filming, and made landfall a day or two later with a fine appetite for his next bowl of cereal. It’s probably fortunate they didn’t meet midstream or the food chain might have reasserted its sway.

The first trip I took to Colonsay was on the MV Columba. She was a much smaller vessel than the big drive-on ferries that are now used; vehicles were swung aboard her on davits in a great heavy net and positioned with much swearing and vehemence in the Gaelic by the MacBrayne’s men. The Columba had a writing desk with its own headed writing paper and tea was served, including cake stands, unless the sea got what is called lumpy. That first trip, I was sensibly attired for arrival at a small Scottish island in a voile maxi dress, bare feet and some sunglasses that had snap-in snap-out lenses in a choice of shades: turquoise, peat or rose. For my arrival I selected the rose-tinted spectacles. That crossing was a fair one and I wasn’t sick at all, though I had to visit the Ladies with its astonishingly heavy doors, fit to cope with a bad swell, to reapply my Biba eyeshadow which was also pink and frosted. I have in my life made this journey only twice, I realise, on my own. At the start of this book I thought it was but the once, when I left the island to do my bit for Man Booker, but of course I arrived alone the first time.

Arrival at the pier at Colonsay, or at any other island, is a mixture of a gathering intensely social and ferociously practical. Families reunite, sick people leave for hospital, children depart for school on the mainland, tractors roll off, the dustbin lorry arrives, a wedding cake must be unpacked with utmost care, a new baby may meet its father for the first time, a bull must be unloaded, a funerary wreath disembarked with due dignity, a body, even, must be consigned. So it’s fortunate that I have no recall of my own arrival at Colonsay. Perhaps, if anyone noticed at all, they thought I was a cabaret entertainer who had got on the wrong boat. Oban was not then the sophisticated burgh we now know.

Scalasaig, the port at Colonsay, is, however, inordinately sophisticated. Let no one think that because a community is small, it contains less nuance than a larger one; the reverse is so. There is no end to it; the place never stops. Like all life lived up close, the feeling intensifies with the proximity. The lens is tightened in upon you and your behaviour, your coloration, your profile in flight, your integrity.

There is a big book about the geology, archaeology, botany, ornithology, zoology and highly variegated civilisations of Colonsay and its tidal neighbour Oransay. Its name is Loder on The Islands of Colonsay and Oransay in the County of Argyll. I mention it because once you have a sniff of the place you will want to know more and here I can but represent it with a puff of cloud, a pinch of air, the smell of crushed bog-myrtle, or the call of the corncrake that lives protected within the island’s shores.

Another addiction warning must in fairness be issued at this point: one of the lowest blows about my blindness is that I can no longer really see to read the island’s online newspaper The Corncrake, that once read takes up its place in one’s reading pattern with a good deal more monthly tenacity than many glossy magazines. It is certainly more European-minded than many broadsheets.

As for the island itself, it grows through your circulation like a tree whose pip you have swallowed without knowing it. It is quite possible to make the world of Colonsay. It is an Eden. St Columba drove all snakes from it.

Oransay, which is attached at low tide to Colonsay, is a holy place. If I were told that I might never return alive, I would ask to be placed with the least fuss in a wicker basket and taken to Colonsay for the residence of my soul. Just as long as, mind, it was no bother. The freight on my cadaver might be crippling. Oransay is for other souls, to whom we shall come.

The island of Colonsay is the ancient home of clan McPhee. There is in Canada a town in Saskatchewan called Colonsay, witness to the Clearances. The New Yorker writer John McPhee has written a book of lasting value about Colonsay called The Crofter and the Laird. In my life I have had the luck to have known that crofter a little; the laird is Papa about whom it is impossible for me to be objective. Even John McPhee has trouble, writing in the early nineteen-sixties, resisting him; the same goes for Ian Mitchell in his far angrier book, The Isles of the West. In addition to looking just right for the part, Papa is an astoundingly sweet fella, as he will say of others.

It is 2008 and Papa, thank God, is still alive. Nonetheless, he is known on the island as ‘the old Laird’ because he no longer lives in the big house, so it falls to his older son Alexander to be the young Laird and responsible, not unlike God in an unblasphemous way, for everything that goes wrong.

But that is now. When first I met Alexander, he was portable. I took to having little children around me with passion. The twins were six, I think. Among ourselves we use the terms brother and sister, and I fell into a habit of ambiguity. It is perhaps among our children that the position is best and most tactfully made clear. My children refer to their ‘not-cousins’ and love making jokes about how they have genetically ‘inherited’ aspects of the Howards simply through closeness and osmosis. They cannot imagine how touching this is to me or how grateful I am to them for it.

It pulls together strands that I myself cannot pull without feeling them heavy as sodden hawsers leading to sunken hulks.

Not only is there no drop of blood in common, save in the most primordial sense, but temperamentally and in every other way I am as unlike a Howard as could be, save perhaps for my height. However, I like to think that this otherness makes me of some use to them as a sort of conduit or adaptor, a useless person when many useful ones are around. The autobiography of a person even temporarily blind must skirt sentiment with care and the subject of a childhood that was at once delayed, invented and almost impossibly beautiful spells danger for the glowing, softened, recreating memory.

There were of course rocks under the dream, but they have proven negotiable, which is a benefit, insofar as I can see it, of family love. From a distance of over forty years, it is not possible for those long holidays from school not to blur into one another, though actually I can tell the years each from each in a fashion with which I won’t trouble my reader now. It was a late childhood and with very particular conditions.

When I arrived in the lives of the Howards, there was no electricity save from little coal generators that stopped at midnight and sulked if you had a Hoover on at the same time as, for example, four light bulbs. This in a house with twenty-five bedrooms, albeit eight of these simply comprising a bachelor floor, as though for visiting swains, ready for eight dancing partners. We had candles by our bedsides, stone hot water bottles, coal fires in our bedrooms and, when I first arrived, ate with the grown-ups in the dining room only on special occasions; otherwise it was the nursery. I suppose I regressed appallingly. Certainly I fell with indelicate speed into calling the parents Mum and Papa instead of Jinny and Euan. Mum read to us after tea, which arrived on a trolley: gingerbread, Guinness-and-walnut bread, drop scones, soda scones and blackcurrant jam. We played dressing-up games and every day involved a physical adventure of some sort during which I would come to some safe small harm, be chaffed a bit about it, and be nursed out of it with affection from one or other parent or child. The parents had that dash and carelessness that goes with having a large number of children. It wasn’t actual carelessness. It was confidence of the physical sort.

When I arrived, the house’s harling was weather-washed with pale pink; it is now pale yellow. At the front it holds out accommodating wings around a sweep of pebbles and an oval lawn, each wing terminating with an elegantly arched Regency window. All around the edge of its front façade at the foot are pale green glass fishermen’s floats like heavy bubbles. From the back, the house looks surprisingly French, an impression not dispelled by the palm trees and tender plants that embrace it. The lawn bends twice deeply down to a cedar tree of great size, a stream and a bridge that leads to the many scented acres of subtropical garden that rise beyond and up and over to the pond and the gulches planted by nineteenth-century enthusiasts collecting from China and the Himalayas. In May and June the deep womanly perfumes of rhododendrons and wet earth almost make the air sag. The Polar Bear Rhododendron smells of lemons and tea with cream. You could make a tea tray from one of its leaves. All rhododendrons of the family loderi have leaves whose backs are soft as a newborn baby’s head, with a downy covering called indumentum. Many of the hedges are wild fuchsia or escallonia. The fairy-like white fuchsia is the loveliest and leads to a part of the walled garden where Papa put (with much indentured child labour) the great glass ridged tower of a disused lighthouse lens from Islay. Sit within it and the world splinters into its seven constituent colours. On a bright day, screw up your eyes for a blinding white inside your head. The lens itself is big enough to hold two or three people. I have been into it once since I’ve been going blind. Its gift on that day was to dress the closest tree of pink blossom in long light-ribbons of green and blue.

The oddity of a closely remembered late childhood is that I might not perhaps remember it in such detail had it genuinely been my own. Nonetheless, it did its binding work. Above the house is a loch called Loch Scoltaire. Each child kept his or her wooden boat slung in the boathouse there. In the centre of the loch is a small island, surrounded by other islets on which terns nest and dive-bomb your head as you row or swim to the central island. There is a Victorian pleasure-house, suitable for picnics and sketching, from which, in the nineteen-twenties, Papa’s glamorous mother might have gone swimming naked before setting up her easel. One summer when Andrew was about six, it was mooted that he was brave and old enough to have me in his charge overnight for a camping expedition in the little house on the island. He was an enchanting child, with a head like a broad bean and an enormous mouth. We set out up the hill through the heather and gorse and over two rusty stiles with our equipment. Andrew was in his striped pjs, maroon dressing gown and those old-fashioned slippers that little boys used to have resembling those worn by elderly gentlemen. I can’t remember what I was wearing, but it wouldn’t have been anything like as practical as Andrew’s attire. It had been made very plain that Andrew was the expedition leader, as indeed he was, since I can’t row. We pulled out the littlest dinghy, Duckling, climbed into her, trimmed our weights as far as we could and Andrew rowed lustily to the small island where we made fast the painter.

We settled down in our sleeping bags. We had brought two eggs for the morning and firelighters and matches. I was to be on wood collection duty. The island is maybe the size of four king-sized beds, the wee house the size of one. We told one another a few scary stories and soon Andrew, dear bean, was fast asleep. The next thing I knew was that we were participants in a really creaky Enid Blyton or Swallows and Amazons plot. I heard the muffled sound of oars and saw the fairy fire. I heard the deadly tread. All the other siblings except Jane, who was too grown up, had accoutred themselves as ghouls and skeletons and beasties. Anyone else in the house who could be persuaded to come along had done so. One house guest had had the idea of laying paraffin on the water and lighting it. But Andrew and I slept through that part of the invasion. It was such a comfortable haunting, safely to be teased by people who had gone to the trouble of frightening one just enough and then arriving to reassure, so that there we all were on the tiny island inside the already small island of Colonsay, sitting in the brick house with six little wooden boats pulled up stern to and painters tied with a round turn and two half hitches. In the morning Andrew and I went home to the big house for breakfast even though our disgusting boiled eggs had been so filling and nourishing.

With great patience, Jinny and Euan allowed me to tag along on all adventures and duties, or to absent myself from them. Katie has also been a lifelong task giver. One summer we were in the fruit cage, collecting gooseberries for jam and bottling for the winter. It was a boiling day and we were in swimsuits and shorts. Little Emma was with us and it was on that day that she told me that the feel of damp grass on her bare feet gave her an occasional sense of nausea. I knew she was a pea-princess then. We had several heavy baskets of red, furry goosegogs and a couple of trugs of harder green ones. Suddenly I made a noise. Katie had trained me to sneeze soundlessly and never to cough, even if I felt like it. But this was a loud noise and Katie didn’t approve of it. We went on picking among the prickly bushes under the net in the walled garden. About ten minutes later I tried to talk and found that I’d lost the capability. I made some more noises. Katie was bent over her picking. She is an efficient and excellent gardener, cook and household manager. She very much dislikes being touched suddenly, but I had to get her attention somehow. I tapped her hand with mine and poor Katie turned round to find me not quite doubled in size and gagging. I can’t remember what happened after that. Someone found some old Wasp-Eze in a cupboard and squirted it on to where the sting was still sticking out of my cheek. I love gooseberries and love picking them, like most gardening chores and especially doing them with Katie, but that time was nearly fatal and now I carry the syringe and pills that the terminally allergic wasp-stung need.

The best of the wasp incident was that every day Papa would say, ‘Claude darling, are you sure you’re all right, you seem to have got bigger.’ So, yet again, he made a comforting repetitiveness that when I started to deflate meant that the other children could tease me painlessly by pretending to be Papa. Later, we discovered that I was also allergic to Wasp-Eze, allergic both to the attack and to its prescribed redress.

The length of the summer days in the North, and the delicious light that lingers, retreats and is reborn, fills my memory with summer evenings when we smoked the mackerel we caught or made moules marinière in a bucket. The sea in summer can be purple or it can be aquamarine and so it is with the sky. Coming back from long days on a beach with one’s young children in a flotilla of boats, watching the kittiwakes and chugging into harbour with the remains of a picnic and piles of sandy tired children has become part of my deep life. One day, we were at sea in a small chunky boat, about eighty years old, like all Papa’s boats an orphan. We were just off a bay named Balnahard where the mackerel crowd. We had our darrows down and were waiting for fish. As a child I loved the gutting and it used to be my job to gut at sea, but since having children I can’t do it. Suddenly everyone’s darrows were leaping and on each hook were not one but three or sometimes five mackerel and then we found ourselves witness to what might have been an illustration of the food chain. From the sea leapt a sparkling cloud of colourless, minute fishlets, followed by a jacquard silver-and-blue arrow of mackerel followed by three perfect, classical dolphins as though posed upon a vase and then, enormously, slowly, holding back time with its size, the huge bridge of an emerging basking shark, three times the size of our boat.

Sometimes Papa might be persuaded, if the evening was flat calm, to take us, as children, and later with our own children, through the strand between Colonsay and Oransay, but at low tide so there was a danger of going aground. The benefit, however, was that when he turned the engine right down and steered as he can by feel, we were among seal families, for it is just off Oransay on Seal Island that the seals go to pup and we could watch them suckle and kiss and roar and chat and sing, the mothers so confident (so long as we kept quiet or did nothing but sing rather than talk) that they did not flop into the water leaving their babies but stayed with them on the kelpy rocks. We have been no more than six inches from those white baby seals with their awful cat-food breath and their black marble eyes. The sea on nights like that was like milk and, going home, there might be phosphorescence in our wake. We would tie up the boat in the harbour and unpack the box full of gutted fish, the exhausted picnic, Papa’s bottle of pink wine and our beach bags, a different colour for each child, with our names embroidered on. I was proud when Jinny said I could sew mine.

I cannot calibrate what the value of this family, and of its home, is to me; perhaps that is what having real siblings is like, but I think not, because I am conscious that it surprises me and delights me constantly, therefore I cannot be expecting it, therefore I surely don’t take it for granted, as one perhaps does the love of a sibling. I also feel that I am more use to them semi-detached than attached and homogenised.

Katie and her second husband William, who have been married for almost thirty years, grew tired of London. Katie is a country girl and needs to hack and dig to make a day feel lived through. William is extremely adaptable. They and their three children moved to a house on the Firle Estate near Charleston. They rented Bushey Lodge, a house that Cyril Connolly and his wife Deirdre had lived in. With driven application they commenced to become organic market gardeners just before the idea had caught on. Katie and William’s market gardening produced aesthetically pleasing vegetables in magnificent abundance. Katie loved the names; she was especially fond of a floppy lettuce called Grande Blonde Paresseuse. They grew purple potatoes and Japanese artichokes and cardoons, tigerella tomatoes, yellow beetroots, rainbow chard and a host of products that the supermarkets have now made familiar. Their project foundered on an unready market and perhaps too much generosity when it came to the accounting. There had also been an element of using hard physical labour as an anaesthetic, for at this point there was a shadow of unhappiness over each of their lives.