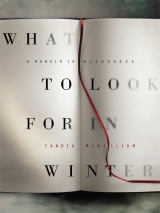

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

It is indeed nothing itself of which we should be frightened.

This book is among his most imaginative work. Apparently conversational, certainly lively, it is nevertheless made of prose so very clean, so deadly serious in intent, that it should hold out longer than bronze, prose that, its author knows, will, naturally, not so last.

These books are under-books, if I may make up a term for the works that form first as clouds then distil then fall during the life of a writer, who is making, or thinks he or she is making, quite other works. They are what else is going on.

The trouble with writing any book at all, though, is that it will produce its under-book, so the process is, by definition, an endless one. During the writing of fiction, this can be a beneficent, even invigorating, force. The shape of the next book consolidates beneath the one you are extracting from the waters. Reasonable enough to object that I can’t have much experience of this, as I’ve not written a novel for so long, but that does not mean they haven’t been circling me, and showing their backs up through the deep.

As a by-product of a memoir already written, the notion of the under-book leads to the sort of puzzle that is by turns a charming and a terrifying idea, one that first took hold in me when I saw in a doll’s house a doll’s house that contained a doll’s house. I think that this realisation of infinite contained diminution comes to every child in one collapsed flash at around the age of three. It then returns, complicating and developing itself, over all the coming years as they pull themselves out of what looked like just the one vessel, but is actually a telescope, diminishing but not terminating – until it does.

My experience of Russian dolls was later, when I was about four, and somehow less interesting, because so well defined, the big capacious hollow doll on the outside, the little solid doll in one piece at the end of the, not actually in detail identical, row. The idea of the infinitude of entities fills the mind much more crammingly than its embodiment in wood and varnish dolls.

I saw the idea animated out at sea off the northernmost point of Colonsay. I mentioned the sight before in my spoken memoir, and round it has come again; it is what lies beneath, coming up each time from further below.

In engravings of sea battles, you may sometimes see in the corner, near the compass rose or churning against a fleet in order of battle, big-mouthed fish swallowing fish swallowing fish swallowing fish right down to sprats, and, it may be imagined, to fish too small to be drawn, smaller than a water drop, a single egg this size.

We were mackerel fishing in a clinker-built boat, adults and children, dipping and shaking darrows with metal and rubber lures at intervals along the simple line. The sea was neatly choppy, then stood still like setting jelly.

A breath was taken, somewhere. There began a sequence too remorseless to have been organised by anything but nature. From the sea dimpled a cloud of million upon million tiny fish the size of escaped swarming semicolons from this page, full-stop eyes and transparent comma tail. Next came the fish the length of little sentences, strips in the air, many more. Behind them and pulling some sea up with them came the flock of good-sized pollock, about a paperback long, soft and floppy and innumerable, followed by the vigorous black-printed hard-backed spines of the mackerel themselves, purposeful, rigid, silvery in flight, determined to avoid whatever it was by leaving their element. Some even fell into the boat they braved in their great print-run of collaborative fright.

In its own time, the basking shark surfaced, voluminous, dark, impossible to read, never seen entire until finished, forming and pressing aside the waters from its back, as slow as the last word, holding time up; as the small fry before it had splintered time into fraught literal quickness.

Our own amateur dipping into that sea for a few fish to clean and split, to dip in oatmeal and place in butter in a pan, was shown up as the interruption we humans are to what is actually always going on.

After that easier time in February of this year staying with Fram and Claudia in Oxford, I understood that habituation was what I must use to drive out habit, and that, were I to be confronted with the reality of their life together, I would not be able to cleave so dearly to some trapping notion of their life’s perfected surface. Not that their life is any less happy than I imagine it, but instead of being as far from it as I can arrange to be and thinking of nothing but it, I can try although I am blind, to see it in truth.

It is not so dreadful not to be loved as it is not to feel able to give love: ‘Let the more loving one be me.’ It was the thing I could do, and somehow I have so scared myself as to feel that even the love I give, that came so easily, to my children, has been chilled by my shutting myself out in the cold.

I’m running out of things to lose and therefore find myself, to my shame, with rather less to give. It happened more suddenly than I had reckoned with. I think that it must be like that for everybody. It’s always too soon.

The weekend after I had spent quite a time in Oxford with them, Claudia invited me to stay again. Toby again cooked a roast with vegetables from his allotment and an aunt of Claudia’s was staying. Claudia has many aunts. There are many parts for women in her family drama.

The oven hadn’t been cleaned for a bit, so there was a smell of cooking. Fram is exigent about smells; they lighten or darken his mood. He was once angry when I made popcorn before Steven Runciman came to lunch at our flat in Oxford. The great student of the patriarchate of Constantinople was then in his late nineties. The air in the flat where we lived was blue with popped kernels and burnt corn oil, a seedy sort of hecatomb. Why did popcorn suggest itself as an appropriate snack?

That Friday evening in Oxford decades later by now in our own lives, Fram was scratchy, though the supper was delicious. I wondered whether it was all a put-up job, Claudia being so considerate of my feelings that she arranged to rile Fram to show me that their relationship isn’t perfect. Or the two of them setting it up, with Toby, spreading carbonised fat on the innards of the stove. Or…these are the tergiversations of my obsession in all its banality.

The evening passed happily, robustly, confidentially. I didn’t cry that much in bed after we had said goodnight and I managed to do what I do so that I will not howl like a dog, which is to have Proust ready in CD form on the turntable of the CD machine I take with me and put on the pillow next to me if I’m in a double bed. I hold another pillow and lie and listen.

Sometimes I wake up in the night and remember that I am I and what has gone before and I burn. My eyes stare open at these times, but what’s the point? They aren’t open, like water to light, for reading. They look at the carnage and they sting from the carbon of the burnt-up days and hopes. I burn with remorse. Its name, Remorse, suggests it is a practice form of death, ‘mors’, though its root is not death but the bite that it holds on the spirit.

No professional associated with the so-called ‘psychological approach’ to my blepharospasm had taken seriously the idea of remorse by this point. Every one of them flinched from any term that implied moral judgement or any system beyond the pragmatic, what you might call, even, the self-centred. How swiftly self has replaced even the sense of social responsibility. There is a free-market psychiatric bias in the establishment.

Perhaps the most rapacious free marketeer so far has been the hypnotist, famous and by all accounts highly effective, whom I visited just once in the New Year of this year. Her secretary took my credit card number. The waiting room offered the usual macabre trailer for what is to come. As has become familiar to me, magazines are laid out with exaggerated care as though they were learned journals, and loose-leaf files of before-and-after shots of plastic surgery procedures are helpfully disposed on a side table near the artificial flowers, that are periodically refreshed with scented spray by outside contractors. In the winter months, there may be a replacement flower arrangement in carmine and spruce. At Christmas the tree will be equipped with shiny empty presents hanging from the plastic-needled boughs.

I entered the studio (too creative in arrangement to be called a consulting room) of the renowned hypnotist, and she addressed me, looking at my woven leather handbag that I’d bought from a hippie outlet online. She spoke one word, which will be familiar to fancy shoppers.

‘Bottega?’ (Bottega Veneta is a, very expensive, Italian fashion house.)

No, I said, my bag wasn’t from there.

She interrogated any of my clothes that were susceptible of such a nakedly undeserved upgrade, and, when I wouldn’t play, she laid me low on a long leather lounger with a sticky bolster for my head. There was an almost fresh towel over it.

She encouraged me to think of a beach, on which I was lying, maybe in company, ‘feeling great about myself’. I took a beach from my extensive collection, a good cold beach, with pebbles and reeking seaweed. I added litter. I am made itchy by the idea of the hot palm-fringed beaches of the brochures, so in a way I was selecting a more relaxing setting in which to become porous to her trickling syrup.

She told me that I was right under now and that men preferred blonde to grey hair, so I might think of getting my hair highlighted. I was there because I couldn’t see, not because I was looking for Mr Anyone at All. Her own hair, I could not help having noticed, was what advertisers believe all men adore to run their craggy yet strangely sensitive fingers through, teased, red, and full of product. She encouraged me, in a special swooping, supercaring voice that sometimes left her grammar in trouble, to find a secret place within myself where I was ‘very very calm’.

I’d rather have been reading a book.

When she started talking in a normal, coarse, ‘real life’ voice again, I sat up and hoped that I could disappear for good.

‘It says on your paperwork you are a writer,’ she began. ‘I’ve written a book. Would you mind casting an eye over it? It’s going to be called I’m Alright, so Fuck You.’

The extraordinary thing is that I didn’t say, ‘I came to you because I cannot see and it is driving me mad.’ I said, ‘Oh, how very interesting. Is it about self-esteem issues?’

‘You are very sympathetic, Candida,’ she said. ‘You could be in my line of work.’

So now I know. I could talk rubbish to desperate people and be paid for it.

I cancelled the next two sessions (you had to book in batches, such was the demand). The secretary explained in a soothing voice that they would have to keep my deposit for the missed sessions. A hundred per cent. It may indeed be my path on life’s winding yet rewarding journey to utilise my prodigious empathic powers to print money with the sad press of others’ credulity. The book, over which no eye of mine had been cast, emerged, and is a big seller. That’s most likely because I went nowhere near it. Unsympathetic magic.

The worst of the remorseful nights have been in hospital, where you are more alone for not being alone. You cannot weep. It would be cruel and selfish, among the sick and dying. And if you start to weep, you may start to howl, and call down the shape that is lying in wait for us all in the dark, coming back at the gallop (or jig, or silent tread) again. Always coming back for more.

The next day, in Oxford after the smoky roast, Fram asked me how to clean an oven. I told him and he bought the materials. Because no one else in the household bothers, he did it, and took pleasure in it. I offered to do it, and with some patience he resisted the temptation to say, ‘You silly bitch, your willingness to clean the ovens of others blind while they pick flowers has got you where you are today.’

While he cleaned the oven, wearing gloves, with bicarbonate of soda, I cleaned the silver, much of it his parents’, that had lived so tidy – though not tidy enough – a life with us, but a tidy life that had let it down. It was now rubbing along with all kinds of impurities and no one was bleeding.

I reunited forks with forks, knives with knives, rubbed with silver-polish-impregnated wool, and realised that I was achieving nothing but the temporary cleaning of some silver, and that it was not a metaphor for anything at all.

If I was cleaning silver, it was just so that the silver might be clean. I had lived my life trying to implement the beautiful ideal of Fram’s subject of study, George Herbert, ‘Who sweeps a room, as for Thy laws, Makes that, and the action, fine’, but I had confused the terms of life and art. I was cleaning a lot of forks that would get dirty again as they should in the ordinary process of life.

I must not place myself in the category of one whose life is not real, since it is the life that I have.

I cleaned the bath, here on Colonsay, doing it by feel, with gloves, and a pungent wholesale chemical scouring ointment that suited just fine. It is dangerous to live wholly through others if there is anything at all impure in your nature. I must put myself out into the warm and light, that I am convinced I do not deserve. I lie cold and burning in the drawer where I have stowed myself away like an old knife, blackening and growing self-sharpening as remorse grinds at me, burning away like this in the cold.

This pain is not even useful.

I think that I’ve seen it off every time, this shameful pain.

But it returns.

It is the sense that I earned my blindness by every lovely thing I saw and my unhappiness by every moment in my life that was good that galls and imprisons me. It is so trite, so dull, so inutile.

It is cold and the doves are roosting in the garden on this island. Soon it will be dark, or the light that passes for the dark in the North in spring.

Chapter 11: Pollen and Soot and the Family in the Cupboard

It is a perfect drying day, blowy, bright. The deep trees and giant rhododendrons over the terraced lawn at the back of the house make coloured walls that swim and fill up all the windows, which are wide open. Although it is Saturday, not a washday, I have washed the sheets and shirts and hung them out.

Many visitors to Colonsay are keen birdwatchers. The chough with its red beak and legs can be seen up close as a soldier in a sentry box, with just that gap for interspecies respect. The probe-beaked oyster-catcher investigates the strand between Colonsay and Oransay with its prying disdainful notation of the polished tidal sand.

Last night, sitting in the sun that brought out the Mediterranean smell of the fennel foaming in Katie’s raised herb bed, we heard the scrawp of the corncrake, Crex crex, its Latin name remaking its call, from the field beyond the white rose hedge, ‘Blanc Double de Coubert’, that smells of vanilla, which she made with cuttings from a hedge at a farm in the north of the island.

On my desk is a withering newspaper cutting. In last week’s Oban Times the regular SermonAudio.com display advertisement carries as its text, ‘Like a bird that strays from its nest is a man who strays from his home.’ As if this were not striking enough to a sinner, or to anyone feeling faintly sad or guilty, the last words of this boxed item are, as they are every week, ‘YOU ARE KNOWN UNTO GOD!’

God, whose search engine is ineluctable. Can I have been the only consumer (I can hardly say proper reader) of the Oban Times who felt discovered, found out, by these words? Is that the point of these texts in newspapers? Their applicability to everyone vulnerable, much like horoscopes, which are designed to touch all who breathe or love or doubt.

As soon as sun is reliable, and the wind is low, there is the chance that midges will arrive. So they came. You can hardly see them, even if you can see. The first sign is that you start to twitch like a dog, and flip your paws at your ears and ankles. Midges are nanotechnologists. They reach places that you could not devise for pertinacity, the base of an eyelash, the shadow of a hair, the inner circle of a bra, the far spiral in the secret ear, the tender meat that would be an oyster or the Pope’s nose if you were a cooked chicken.

Inside the farmhouse, itself still used to being cold after many winter months, Katie lit the stove with kindling, put in logs cut by William from the dark windbreak pines he is steadily thinning, and closed its small iron doors over the flames in the bright daylit room. You grow used to many kinds of weather in one day, in one house. Sometimes there are several weathers at the one time, a different squall or new sunbeam for each face of a house. Weather claps soon against itself, so that an unmixed day of sun or unvarying rain seems to last longer than other days.

At nine o’clock yesterday evening, I was back at my desk in the big house, which is also table-of-all-work and dining surface, in the old nursery that is now a sitting room. Two hours of light to go, at least. Two arms of yellow dwarf azalea were dying in a dull brass vase with a smell like leaf mast and honey, too good to get rid of, though the flowers are falling in little yellow dabs and flecks down on to the table, where they stick because they are so full of nectar.

Two of the petals of Meconopsis, the blue Himalayan poppy that loves the island soil and that Katie grew from seed, have fallen from the single plant with its one four-petalled flower that she has given me in its plain pot to have beside me while I work. The fluffy pistil sticks out beyond the ring of stamens whose anthers are golden yellow with pollen, not the sooty ring of black dusty anthers at the centre of most of the poppy family’s flowers.

Like all blue flowers, it looks like an idea. Speedwell, forget-me-not, the blue poppy, the Scottish bluebell (also known as the harebell), chicory, gentian, plumbago; they recall bits of fallen sky.

The sky that is, we are told, not itself actually blue. Perhaps that is why these flowers are like abstractions.

As well as being a great novel, The Blue Flower by Penelope Fitzgerald has a most suited and suggestive title, evoking, as it does, the short life and foreshortened love of a philosopher from a northern country, Novalis. A blue flower is the plant badge or emblem of the kind of otherness, natural unattainability, sought in some areas of German Romantic thought.

All flowers summon a sense of their transience that intensifies their effect upon those susceptible to their spell, plump double flowers or the fleshy hard-wearing flowers to some of us proportionately less so.

Blue flowers seem ineffably more transient and frail. Fragile is too strong and consonantally pegged down a word for it; these flowers are frail like faded worn cloth or like those patches of sky. They are remote, as though glimpsed. They are slips of things, a hint, like very young people in the one summer when they know they are lovely but do not know the effect of it, or the sea around the next bend, or fresh water between mouth and thirsty throat. They are half-seen. Once you have lived for a certain time, a blue flower makes you at once satisfied and sad.

You can’t keep it. Even the seemingly robust hyacinth is an emblem of vanished masculine beauty, for the drowned curls of young heroes. If you press a blue flower in your prayer book, its petals turn purple unless your prayers are acid-free.

The poem ‘Vergissmeinnicht’ by Keith Douglas, who was killed at twenty-four in the Second World War, flowers across borders of notional nationhood with its description of the words in the notebook of a dead young man, in his Gothic German script, telling his girl, Steffi, not to forget him. The myosotis around the door of the church at Balbec are what the enraged Charlus upbraids Marcel for failing to recognise—‘Ne m’oubliez pas!’

When I looked out through the flawed glass of the windows in the evening of Friday, as well as through my own already flawed gaze, I saw the shadow of the house thrown out on to the waving, shimmering leaves of the big trees. Three chimneys measured themselves along those wide trees, and the long line of the roof offered its shadow along the lawn and the lower reaches of the trees whose individual leaves were still holding sparkling doses of light.

It is unusual to see a solid thing made insubstantial against a moving surface, but shadow had its say. Nothing lasts. There are as many ways of looking as there are of seeing. Do not think you have seen it all, just because your own sight is changing. The new leaves of the copper beech were almost transparent to the late sun, rippling, moving at a different rate from the leaves on the smaller more susceptible trees, the beech’s leaves rhubarb green and pink under the plain blue sky.

At three floors, the house is lower than the trees. The trees and the house have different rhythms of regeneration; that is all. The lengths of their watches differ. The trees measure by the life of their leaves and fruit, the house measures by the years between the birth of one human generation and another. Between the trees and the house, pups lollop then dash into dogdom, go grey, stiffen, settle, stay by the stove to dream of dash and lollop and at last die, each taking a human childhood to make their life’s full circle.

On the mainland, Angus’s heart is beating itself better, under observation.

Why lead my life if someone else can do it better?

Most of my experience of the last ten years is not undergone but envisioned, prefigured, particularly so, and I say this without regret, since I came up here to the island to separate myself from my own various forms of incapacity made worse by blindness. My experience has been not precisely second-hand, but often vicarious.

What is the opposite of a stalker? I do not mean the one who is stalked. I mean the one who seeks to be consumed by the fire in the lives of others, the one who is made more shadowy by others’ lightness, as opposed to one made more real by their glaring lack of substance.

It is all too many of us, since this unholy loss of self and rampaging, insecure, hunting down of reasons to be unhappy is probably what makes people buy magazines.

Yet Fram and Claudia, unlike film stars, whose sway and revenues depend upon it, do not want to be lived through. They live through one another.

The magaziney vicariousness is a decadent state in which to wish away a life. On the weekend in Oxford when I cleaned the silver and Fram cleaned the oven, I thought that something was repairing itself, or, perhaps better, something new was knitting itself.

You could interpret what happened next as the necessary consequence of thinking too much in terms of metaphors. Claudia had a quiet friend staying, I’ll call her Antonia.

Our son had two friends for dinner. They both had dead fathers and mixed backgrounds: American, Russian, Israeli, British, Chinese, Filipino. They had the unforgiving beauty of the very young, but the company was good and I hardly felt odd. Minoo was enjoying his ‘two mothers, one father, one father’s girlfriend’s twins’ father’ caperings. I thought I was taking things pretty lightly and not coming over humourless at the scene. The happy table stretched, as it does, to embrace whoever comes.

Everyone over thirty was quite tired. Fram and Claudia had been working all day. I am always tired. Living with my hot big not quite mended leg and half-cut eyes tires me out.

But everything was going well. I hoped Minoo’s friends were enjoying their look at his family.

At one point Fram said, with the weight of a gnat, not even of a gadfly, ‘If Claudia dies, I will marry Antonia.’

It was just a sally. I saw then that he really is free of me. The thought that he is married, in fact, to someone else didn’t occur to him.

Not a feather fell from the dove I felt had been taken by a hawk not five feet above our heads at the table. No one noticed a thing, nor thought it. Only I, and I had best get over it.

There was no reaction save within me. They were modern youth and we were modern adults. There was nothing to notice. But I collected it and swelled inside from the allergic reaction, the anaphylactic shock, of the midge-bite that I took as hawk-strike.

That’s it. I have it. Anaphylactic shock is what I go into when there is talk of marriage, of husband or wife. I carry a syringeful of Adrenalin to restart my heart in case of being stung by a wasp, but it is quite as important to carry a syringe of thought within my mind for these occasions that will go on for the rest of my life, when marriage or something relating to it comes up.

By the time everyone went, I was red inside and swollen and finding it hard to breathe. When I spoke to Fram, trying to implement a new version of myself, one who spoke up when trodden on, he was angry and bored by what I had to say and said that it had been meaningless, that the terms had no weight and he was tired and wasn’t thinking, least of all about that old stuff, that had no meaning. None of it meant a thing. It was very late, he had been working on papers till four the morning before and was exhausted.

All fair and reasonable.

I took myself to my bed in Minoo’s room among the memorabilia of his parents and grandparents and settled with Proust and the machine that makes him possible.

Claudia said, ‘Don’t present him with despair he can do nothing about. It is horrible for him.’ She is good at him like some people are good at croquet or, more seriously, chess. It is difficult in every dimension, but those who love it rise to the difficulty and wish only for more dimensions through which to engage with this completely absorbing game of systems, traditions, feints, tactics, glamour of thought and an infinitude of reciprocities, as many as those grains of rice my mother-in-law once told me would fill the world if you factored them up on the squares of one single chessboard, moving by a certain mathematical sequence that I now forget, or was it she who never knew, and each grain inscribed countless times itself with the name of the beloved, like the rice grain she was allowed to look at as a child in a dark family house in Bombay, the grain taken from its precious casket kept in a cabinet, a single white grain that bore, she was assured, the thousand thousand names of God written upon it with a diamond nib; and how could she ever know that this was not so?

It decided matters that the grain was small, white, much like any other grain, yet it looked, in its silver-hinged, leather, velvet-lined case, taken from the cabinet, in the dark room in the big dim house in the enormous city of Bombay, to the small girl, like no other rice grain at all in the history of the world, being alone, and, in contrast to all about it, so very small, so very white, so intensely only itself and apart from all other grains of rice ever.

So what is to be my syringe against the sting and swell when I try to contemplate my state with clear eyes? How to make a net with plenty of holes and quite a dearth of string?

It has to be words, after all and not the mathematical equation I was struggling for in Hampshire when grounded by my leg. I love the idea of mathematics, but I can’t seem to carry arithmetic with me, so that I relearn principles again and again and fail to make them part of my equipment.

I need a short formula of words for topical application, when the shocks, as they will, come, and then, after I have stuck the jag into the vein, I can retire from panic into calm and listen to, or maybe even read, the longer reaches of words that lie in books and keep on seeking the way best to live.

It is Sunday now. The necessary words may have been there all along.

Cymbeline is an odd late play made of parts that fit together but roughly, some sophisticated, some simple. It contains lines to which people return because sadness has never been so consolingly expressed in spite of the dislocating oddness of the actual scene in which the lines are spoken.

‘Fear no more the heat o’ the sun,

Nor the furious winter’s rages,

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages.’

The refrain brings pollen, soot, dust to life as the atoms to which we all come. It begins with sun and ends in dust; it is astral physics in poetic form, in a couplet. Two lines of English verse then tell us we are children of the sun, and made, all of us, of sun and dust. That black chimney where the sweeps work is where we are caught in life, even golden lads and girls. There is a view of the sun from the constraining dusty black. Some few are for a time out in the sun. All come to dust.

‘Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney sweepers, come to dust.’

But it’s not those lines that I have been keeping by me, against such a demand as I’m presently making for a prophylactic line, so much as those mysterious words,

‘Hang there like fruit, my soul,

Till the tree die.’

I have loved them for years, and do not know what they mean. Or, they may be made to mean a number of things. They are not imprecise. They speak whereof most of us had best not try to speak or it will be wind and piss. The impression they make breathes out from within them like sea from inside a chambered shell. They express a great perhaps. These were Rabelais’s, almost too perfectly conclusive, last words: ‘I am in search of a great perhaps.’

The circumstances in which this line and a half is spoken, by Posthumus to his estranged wife Imogen, are not, nor can ever be, comparable to what has happened between Fram and myself. For us there is no return to what was before. Neither present truth nor passed time permit. Our separation may have been based upon a misunderstanding, but the misunderstanding was all mine.