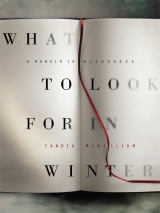

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

LENS I: Chapter 1

I have conducted my conscious life for as long as I can remember by suppression, and so this is, or threatens to be, the sort of book which I am not temperamentally suited to write, an account of a life lived, not transmuted into fiction. For me the fiction had carried the deep truths behind which I had felt able to retire, and to carry on weaving it.

Some writers, from Henry Green to Hilary Mantel, can manage this poetically veracious memoir-writing naturally. I read the best of them with pleasure and fascination. They illuminate without glare and delineate privacy without harming it. The memoirs I shrink from are accounts of profitable suffering; no, profitable accounts of suffering.

I can’t imagine that this book will be profitable in a pecuniary sense. Yet I know that any suffering in my life—‘suffering’ may be too extreme, too official, too martial, above all too tragic a word for whatever has happened to me, though maybe not for what I have brought about – might be of some use to someone. I am porous to the pain of others, but just of late have got stuck. I am fogged up. Here’s why.

It has been brewing since I was five, I know it now. I found that the way to distance oneself from discomfort was to trap it in not spoken but written words, and that, similarly, the way to hold fast to the good was to try – much less easy – to do the same. I was greatly helped in my project by being a fat child. I was good at sitting still because I wasn’t any good at moving. It was my good fortune to have two parents who never stopped making marks on paper and the richest part of whose lives were led in her imagination in one case and his intellect in the other. I copied them.

Why start on this now? In 2006, anxious about money and aware that I was about to start out aged fifty on a life alone, in Oxford, a city in which I had taken twenty years not to feel at home, I accepted an invitation to become a judge of the Man Booker Prize for Fiction. I was a sedulous, note-taking, reader of contemporary fiction as well as a lot of other stuff, and I thought I might as well harness my habit. I liked either the actuality of or the sound of the other judges. I wasn’t wrong to.

The entire process of judging fiction is difficult to defend or articulate and painful even – especially? – for any ‘winner’ of tender conscience but, insofar as it is possible, we remained pure. Early on, the Chair of the judges’ committee had given me a fine piece of advice: ‘If you fall in love with one book you will be setting yourself up for heartbreak,’ she said. I took prophylactic measures, and fell in love with three or four.

After the first judges’ meeting, which took place in the solid surroundings of the Athenaeum, I went to visit a friend with whom I had been at school after I was sent away from home in Scotland. We have known one another since we were twelve. ‘What is wrong with your face?’ she asked, and offered to balance teabags on my eyes, which did indeed feel wonky, despite the soothing light of a grey spring day in St James’s Square. My eyes juddered in their sockets as though they were coming loose and they were hot and couldn’t settle unless I told them to. So the implicit pact between intellect and eyes, eyes and reading heart, had to be declared and had already begun to involve willpower instead of consolation and ease.

I had noticed that I was having difficulty holding the gaze of anyone who was talking to me, but had, characteristically, ascribed this to even more reading than usual and an unadmitted struggle with sleeping, especially through the hours between two and four in the morning, the time when suicide suggests itself and addicts give in.

I kept on reading, of course. Twice, I visited GPs, who each prescribed eye drops. I was aware that I couldn’t deal as well with people as I had been used to, because I couldn’t hold their gaze. I wondered if this was a late-onset affectation, like a fake stammer to imply an engaging tentativeness. But I couldn’t employ my will over my eyes, couldn’t respond or beam or seek or console as I had always – I realised – been used to doing.

My stint as secretary of one of the Alcoholics Anonymous meetings came to an end and I was relieved, as I had relied upon my intensity of gaze, my peripheral vision and my attunedness in order to intuit who needed to speak when and for how long.

From my father I have inherited the characteristic that I am irresistible to panhandlers. University towns are rich in such people and I have all my life felt that I am one. There’s no gap to mind. Most of the beggars in Oxford know my name, or a version of it. My chief heckling bridesmaid at the time was a rather cross, sometimes violent, highly intelligent alcoholic, named Man. By the cashpoint one day he said, ‘Ere, Candice, what is wrong with your eyes?’

I visited an ophthalmologist who laughed handsomely at the amount of reading I reported myself as doing. I found that odd, in Oxford. I doubt that I was reading as much as, for example, many dons, or my neighbour the Reverend Professor Sir Henry Chadwick, whose elegant figure might be seen daily as he got into the car on the way to the library in order to set about the Early Church with grace and vigour; and he, after all, was rising to the challenge of manuscript with eyes that had been working for all but a half century longer than my own.

I was reading those soft options, novels, printed (one might have thought) in typefaces congenial to the eye, faces confected to encourage and reward the process of reading.

I got more drops.

I took seventy or so books home to the Hebrides, where part of me had been a child. I rented a wee cottage down the drive from my adopted family, so that I might work. My family visited on a generously formal basis. There were painful family events occurring, than which any passing funny business with my eyes was far less harrowing. Also, my sisters, who are not really my sisters, each noticed, with her own fine eyes, that things had got better with those bad peepers since I had ‘come home’. That was so. The air in the Western Isles is cleaner than it is in Oxford. Certain stresses were removed. I read around seven hundred pages a day, took notes, wrote letters. For the first time since late childhood, I did not accompany my family as they walked around the island. If I had done I might have fallen off it, but I didn’t say that to anyone. A heron came each morning and stood in the burn among the reeds, his small knees like knots.

I went across to Edinburgh, leaving the island on my own for the first time in my life. I cried when I left as the sea widened between the ferry and the island. I do not often cry, but crying has proved to be one of the few things that wash clear my sight, however briefly. I’ve been trying to take it up more.

I watched the island go, and the other islands pass: Jura, Islay, Mull, the Grey Dogs, the Isles of the Sea.

I went through, as the process of crossing Scotland’s waist is called, to Edinburgh, did a reading over breakfast of a short story or two to an audience in the mirrored tent at the Book Festival, which has been a kind of annual transfusion for me in the many years during which I have read more than I have written (which is not hard), and then bolted for a train down to London for another meeting of the Man Booker Prize judges.

I’d been going to fly, but a terrorist incident had grounded all planes and put the nation on its guard against, among other things, carriers of lipstick, scent or fountain pens. Guilty on all counts, I packed my longish frame and a 900-page novel into the vestibule, as the greased-up hinge between carriages of a passenger train is fabulously designated, of a southbound train, and settled to some hours’ standing room only.

I minded even more than usual being photographed, as we all were, for the long list press meeting. It wasn’t – only – vanity, it was an acute sense that I couldn’t open my eyes. But when making a point or really engaging with the other judges, I could momentarily see into their faces. I realised that this peeled state of being was mind-altering and, while quite useful for an indentured servant of fiction, and a state desirable if it might be useful to the artist in one, not much good in a mother or a friend.

I returned to the North, relieved to be leaving the Quaker club where I had been staying in a bed off whose end I hung. In the night I had met polite dressing-gowned ghosts of either sex in the corridors, between fire doors, up in Town for a play or to clock the City churches. In each room at the club is a list of local things worth visiting which reads like a list of my great-aunts’ enthusiasms, those penurious educated lonely accomplished women. I could feel the fulcrum tipping as I passed into my own past and with some relief felt young no more.

LENS I: Chapter 2

In Edinburgh, as always happens, I took a lease of life and shared it with my younger son. We had a happy few days listening to authors, a really peculiar thing to enjoy doing, but we do. I continued to see jokes and architectural detail, two things that keep me going, though only as it were in stroboscopic clatters of vision.

My son returned to school and autumn was upon us.

Opposite me in Oxford lived two neurologists. The wife was slight, pretty, part-Chinese. By now, if I did have friends to visit, I was experimenting with wearing a green hat indoors to see whether this soothed my sight. I had accommodated to the difficulty of combining walking with seeing by capping the reclusion I had been working on for a decade with completely hermetic habits. I had stopped attending all meetings, including AA, save those for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction 2006.

I visited the GP once more and met a new doctor, young, surrounded by books; on his wall – I saw! – was my favourite New Yorker cartoon, showing a snail in love with a Sellotape dispenser. I told him what had happened, that my world had narrowed quite and that I found it difficult to open my eyes.

He used a word that made complete sense, a direct lift from the Greek. It was very rare, he said, but it did exist. The word was blepharospasm. Blepharon comes up a lot in Homer, and is the Greek for eyelid. Spasm was it.

I was relieved that I had not been making all this up.

My neighbour the pretty part-Chinese neurologist knocked at my door one dusk in September. I wasn’t actually wearing my green hat, as I had been alone. Nor was I wearing sunglasses. I could manage by, as I had come to think of it, ‘striving’ with my neck and chin, to focus a bit and gather from her outline who she might be, and I could smell that she had quinces about her person.

‘Can you not see me?’ she asked.

‘No, not really very well.’

‘I’ve got some quinces from our tree,’ she said, ‘and you have blepharospasm.’

And so I do. My eyes are fine, my vision acute, but my eyelids will not open.

In order to gain sight, I grimace, stretch, peer and above all hold taut and high my already rather camel-like head with the result that I look, if I do go out, like the caricature of a snob. Mainly I take steps so as not to emerge from my tall thin house whose many and irregular stairs fill me with a reinforcement of the dread of falling to my death downstairs that I have had all my life; my parents’ house in Edinburgh had sustained such a death down its stone stairs, I had always gathered self-propelled; that was part of the reason they could afford it, I think.

I now have the elastic-braced white stick with which I hope to dispel the impression of a monstrous dowager with Tourettian facial tics and the creep-and-lurch gait of a not sufficiently surreptitious drunk. Also, of course, I don’t want to embarrass people, or to oblige them to ask if it is getting better. It doesn’t.

In some cases it can be alleviated by the injection of botulinum toxin, which hauls me up for my ugly pride in declaring that I’d never have facial ‘work’, as puritanical fans of plastic surgery call it. I clamoured for the injections now. In Scotland we call them jags and I had four jags in each eye, always praying while the needle goes in that I am somehow buying off Fate for my children and those I love, a dangerous deal and foolish, the worse and worst always offering themselves to the inward eye of a parent.

And as my eyes have closed, so I have learned perforce a number of things, some of which may even be passed on or rendered down, as those quinces were, into something useful or reminiscent or nourishing or maybe merely scented with something that reminds you of something else. It was as if my deep brain was telling me that I, with my lucky and unlucky life, have seen enough and that I really am for the dark. I must catch the light and offer it around, like those quinces and that insight from my generous diagnostic neighbour.

And of course it is not telling you a secret if I confess that I am blindly hoping by hunting down the light, the past, those lost places and people, to lift at any rate some of the stone that has rolled across the mouth of my cave.

My youngest child asked me, ‘It is a vulgar question, but, may I ask, do any of your other senses compensate yet?’

One of my sisters who are not my sisters declared, and it comforted me about her decided unchangeability, ‘Well, we always said we’d rather go blind than deaf.’

How dared we?

How lazily I have assured dying friends that they look well, how idly nodded when people mentioned the unerring ear of the blind piano tuner. Now is the time for me at any rate to pay attention and look hard, close, even if only upon what has been.

This might be as good a point as any to say that none of the treatments described in this book was covered by private health insurance. I did not have it.

Books have been throughout my life very much more than mere consolation and escape, but I cannot deny that they have, and the act of reading itself has, been that too. I now read with a certain amount of difficulty, and can do about a paragraph at a time. Reading in bed is not the bower it was. I cannot at the same time both lie and read, as I have, in the prone not mendacious usage, done lifelong. Reading is tiring which it has never before been. I have all my life eaten books, walked and run and done all I cannot actually in person do among, within and around books, and now am trudging and lagging. Nothing however that insists upon concentration, as this limitation does, is all bad. Memory grows less swooning, more muscular, recall more instructable, like a messenger, and as potent and alarming.

Most things had I thought gone wrong in my life by 2006, but there was always reading. Well, is there? Not in the old sense, the wandering, greedy sense, no. But, even if, in the worst case, I am left no longer able to read, reading will of course remain within me. I used to think, when I was five or six, at night in my nursery, that I would certainly die for books, for Greek and Latin, for words (of course I didn’t think of it then as freedom of speech); I know I would surely give up my own sight of them for these things’ sake.

I peg up my thinning eyelids with my left-hand thumb and little finger, wearing them through. This is called by doctors ‘the sensory geste’ and it’s a sure sign of blepharospasm. There are gadgets, of some of which I am afraid, most especially the metal loops, called Lundy Loops, that clamp open the perusing eye that then must be moistened with specially measured sterile artificial tears. The unfortunate echo of Belloc’s tearful Lord Lundy—‘Gracious, how Lord Lundy cried!’—seems all too apt. It all feels too metaphorical and too true. I have always felt people’s eye stories in my own eyes, cannot watch enacted scenes of blinding, the cloud crossing the moon, or even, truly, the cutting into a fried egg; I fear to read of Odysseus grinding the hot tree trunk into the Cyclops’ only eye.

The already challenging narrative of 2006 folded symmetrically closed, the judging eyes upon and against the judging dark, and the truth, had I even known it, could not, in the little pond of the ‘book world’, have been told. The hilariousness of a blind judge for a literary prize already buffeted by vulgar attention might have done an indignity to the prize or its sponsors. Before the actual dinner at the Guildhall in the City of London, I had to tell the public relations people for Man Booker, Colman Getty, that I was ‘functionally blind’. They were jolly nice about it and sat me with clever, tactful (and dashing) friends. They agreed that it must not be known and asked that I not wear dark glasses, which can offer relief from the juddering and facial tics. Later that week my daughter told me that someone, a literary editor, had told a newspaper gossip column that he had been on a deadly dull table. The columnist noted that this was my table.

I had bumped into the chap who had me down as deadly dull afterwards, as I slipped off (a system agreed with the publicity firm) before the sorrows-drowning, gossip and commerce began in earnest. What I couldn’t tell him, as I no doubt hurt his feelings by not recognising him, and hurt his pride by bumping into him and towering over him, was that I couldn’t see him. I’m sorry I bored him that night at dinner. I couldn’t think of any way of letting him know that did not let him know too much.

So now let me try.

LENS I: Chapter 3

The City of Edinburgh, heated, when it was, by coal and coke and paraffin, had not yet been cleaned. Its grave beauties were still black. Snow fell in the May before I was born. Black-and-white pictures display it all pretty much exactly as the city looked in colour. Scotland, East Coast Scotland, after the war, was cold, dirty, architecturally grand and architecturally ravaged, sumptuarily poor. Ladies over a certain age wore hats indoors. The smells in the street were of wool of stone of coal and, at home in Puddocky (which means: ‘The home of frogs’, fit for frogs only), of the pong of hops and yeast from the brewery at Canonmills, down by the Water of Leith, where the flour for the church’s canons had once been ground. We lived just a stone wall from the river, which was prone to flood. Our house smelt of wet washing, polish, joss sticks, my mother’s Je Reviens, and cats and their requirements. Our whole street had been condemned.

My mother boiled ox-lights for the cats. These enormous organs arrived full of air and redness from the butcher, Mr Wilson, and then clopped down, frothing in her jam-making pan, to chewy brown boxing gloves, under the meaty scum. She deflated them further – they hissed – into manageable chunks with kitchen scissors that I have now, sent down south to me thirty years later by my stepmother in a consignment including my toy box and a Fru-Grains tin, all transported by the Aberdeen Shore Porters, the world’s oldest removals firm, established more than five hundred years ago to move fish at the harbourside in that silver city.

The kitchen scissors were for kitchen jobs only, the sewing scissors for thread and cloth, and the paper scissors for paper alone. The pinking shears were so heavy and specific that they lived in a holster in the sewing chest with the button box, the cotton reels and the Kwik-unpik, a natty hook for the slashing open of stitches in order mainly to ‘let things down’, or to ‘let things out’, terms perhaps now unknown outwith the psychotherapeutic context. There were few rules in my childhood under the dispensation of my mother, but the scissor rule was set. Paper blunted the sewing scissors and kitchen work dirtied the paper scissors. And as for the grapes – they were a luxury to eat (or was it drink, so wet was their taste and so otherwise seductive?) and to look at, so at all times blunt silver grape scissors must be used, like a little flat bird skeleton with a toothed beak, so as to keep the bunch groomed and uncorrupt. I would take grapes with my fingers and leave behind the damp pippy stublet; mould then might spread through the bunch. It seemed I was always found out. If I was caught mid-theft, I would rush to blind whichever parent it was had found me with kisses so that they would not see that I had been greedy and failed to use the scissors. So kisses were connected with distraction and misdeeds – and, it’s true, stealing fruit. This book will be a struggle to find that Eden when they were both about, my oddly paired parents, both, incidentally, lovers of pears, and each devoted to a separate means of paring pears. She made slivers, he made hoops.

Another firm rule was that you must never – ever – write on nor fold down the pages of books. I have not obeyed this rule at all thoroughly and as a child was even worse, for I ate the corners of the pages, gouging out soft thumbsful of paper at the corner, chewing it, and collecting a ball. I was making paper, I suppose. An owlish child’s pellets.

It is hard to convey to a young reader the frustrations of my mother’s life. She was of a generation of women so much less free than my own, as mine is, I hope, less free, or more unrealistic, than my daughter’s. I am a poor example of any kind of liberation. ‘Are you a feminist?’ I was asked in my middle thirties with I knew not what kind of weight. The questioner was a colonial tycoon. I was nibbling at the sort of lunch thought suitable for reasonably attractive married women at that time in history, when the man was paying.

I replied, unforgivably, I think now, with a sort of, ‘Let’s assume that it’s been more widely achieved than that’ gesture. This man later went on to murder his wife. There’s no conclusion.

It is hard for my daughter to imagine the life of her grandmother, a woman of intelligence, allure and independent mind, who disappointed her father, her mother, and husband by being too much of all of it, too tall, too original, too keen to be the little woman, too anxious to conform. Me she did not disappoint, save by disappearing too soon.

My parents’ marriage was a practical disaster, as I felt it. It commenced in passion and was rooted at any rate emotionally and artistically, though only for brief times geographically, in Italy, a place which was in those days even more of a state of mind than it is now. I felt these undertow loves under my parents’ more ragged love. My parents often spoke Italian to one another. She was Scots-Irish and he was Irish-Scots. Both were anglicised, that is they spoke with what we would now call old-fashioned upper-middle-class English accents. He corrected her pronunciation of the word ‘orchestra’. She, like the mother in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, did not call people ‘dear’ like Scots mothers, but ‘darling’, and sometimes even ‘dulling’. Of course it was embarrassing. I do it too.

They didn’t want more of me, and I have been told they didn’t even want me. It’s an odd little thing for someone to pass on to me, and I’m not at all sure that they felt like that. They were worried all the time about money and they fought about it. They both hit one another. It almost certainly hurt each more than it hurt the other. I pretended to want brothers and sisters; I don’t expect I did. I knew things were desperate between them and it is one of my fervent and impure occasions for relief that I haven’t any whole siblings. Impure, because that way I have my mother to myself, I suppose, and I’m not proud of that.

I did have many dolls whose names, characteristics and academic records I kept in my ledger; any dolls not at the front of that day’s routine or drama lived on my nursery chaise longue, which was called ‘the chaise longue’, just as the tall bookcase, where the Petit Larousse I had for my fifth birthday was kept, was called the ‘secretaire’; my father used the correct words for things, my mother not always, though she could taste words exactly despite not being almost painfully good at pitch as my father was in music as well as in language. My dolls were ranked by strict precedence related to length of tenure. After my father’s remarriage they went to live in a box at the top of the stone stairs known as ‘the coffin’.

My mother took the contraceptive pill in an early form, I think. We visited a family whose father was a sculptor one weekend in Kinross-shire and there was a dash to hospital after the youngest child ate the medical contents of my mother’s handbag. I don’t know whether the tranquillisers were in there yet with the Pan Drops and the hanky that she used to scrub at my face with lick like Tom Kitten’s mother in the picture, and the lipstick that smelt of wax roses and the Consulate cigarettes and her dark glasses with the pussycat slant and her copy of The Turn of the Screw, or whatever it was she was reading at the time, but that’s one I remember.

She left over fifty lipsticks at her death and I used them up in a furious winter of drawing nothing but sunsets. What else was there to do with those lipsticks than make sunsets? My mouth was big enough for all those lipsticks to go on in candy stripes but I was nine; and anyhow she had left a lot of blank paper that needed covering by some means. I still have rolls of it that came south with the Shore Porters in the nineteen-nineties.

The cats were too plural in that crammed house in the Crescent. Before I was born the tortoiseshell Nancy Mitford, who enjoyed Dundee cake, had died. My mother’s passion for The Pursuit of Love, which she read aloud to me, lasted all her life. I think that she was, although so differently extracted, like sad adored Linda Radlett, and knew it; the same affection for Labradors and the same instinct for rotters. My father was not a rotter. Among the cats there remained grey Godfrey Winn with his small lopsided moustache, Peter Quint who was my mother’s fat-footed grey plush familiar, and Lady Teazle, a sealpoint Siamese of the pansy-faced, silk-stockinged sort, whom my mother took shopping on a lead.

This in the days when tradesmen in Edinburgh wore different-coloured cotton overalls, like indoor coats in cotton drill, the shade according to the trade, the tobacconist Mr MacDonald the only one who wore an uncovered suit. Mr Cockburn, the ironmonger, wore a cotton coat in grey, Mr King the grocer in royal blue, Mr Dundas the greengrocer, who kissed my mother one year under the mistletoe, in green of course, Mr (Charles) Wilson in pure butcher’s white.

Later, she added to the household. In the background there were as many make-believe horses as you can fit imaginatively into a crumbling house belonging to an ascetic bibliophile who doesn’t care for animals and an insecure hoarder with a menagerie habit, and the solitary child they bred.

My mother was horsey, to look at and by temperament; she would go out to the suburb of Liberton to a stables to ride a horse called Lady Gay. I rode the arms of the burst Regency sofa in the drawing room, perfectly happy with picking at the horsehair stuffing and keeping any actual animal content as remote as that. She loved all horses and waged a campaign to get blinkers removed from the dray horses which brought milk from Murchies dairy, where they still patted the butter and stamped it with a thistle, and from the giant Clydesdales who rumbled along with beer barrels to the pubs or loads of bluish-sheered coal under the tarps. The horse would stand at a massive mincing halt in the road outside the house while the coalmen hove sacks on to rests of greasy hopsack on their shoulders and chuted the noisy coals down into what Edinburgh folk call the ‘area’, then shovelled it into the cellar where the Indian lady lodger saw the black rat and where years later I put kohl on my eyes before the Scout dance at St Cuthbert’s church, aged thirteen, for make-up was not allowed. I was six feet tall already then and they were right about the make-up. I looked like a caricature without underlining any of it.