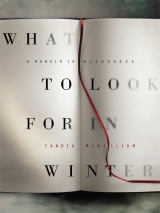

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

I wish that these lines, which I have kept by me for years in case of emergency, were not spoken in circumstances like this, if it gives any impression that I dream that reconciliation of this sort may be brought about. I do not. Another sort of reconciliation, yes, but not the reconciliation of the child awaking from nightmare ‘as though it had never been’. That is for dreams, romances and plays, places where time means what the dreamer or the playwright says and not what time itself, in our reality, comes to mean. I would like to take the words out of their situational context, if I may.

Anaphylactic shock, when you break the word down, means that you are without a guard against the shock. Prophylactic means that something works as a guard. Phylax means guard.

The mysterious, literally almost pregnant, line and a half from Cymbeline slips to its stilled reader the imperative to remain living until there is no life. It is a line that is hard to break down, but by no means obscure. In logical terms, it is easy to take exception to the suggestion that fruit can be longer-lived than a tree, though that is unnecessarily literal, since what is being spoken of is not a fruit but a soul. Posthumus may be addressing his wife, or his own soul, or she may be his soul; surely all of this is intended to be within the reach of the words. The ambiguities are smoky in a play that splices ancient Britain with Renaissance Italy. The line and a bit are hard to catch. They are, like blue flowers, glimpses.

This line fumes with the negative capability that shows us what can happen when certain full notes are struck, one after another. The rock cracks and a seed is set.

What is the ‘tree’, here? Is it Posthumus, the husband, himself, addressing the wife who is clinging to him in their reunion? Is it Posthumus himself, bearer of his own soul? Is it the body? Is it life? In my prophylactic application of the line, I think that it is necessary to take the step of saying that, for my purpose, the tree might have been Fram, but it must now be the impersonal stand that is my span of life, from which I hang, perhaps as passive as a fruit but full of something even if it is only an extract from the tree. Fruit may offer consequences, from wisdom, the apple, to hospitality, the pineapple, or a periodic sentence to hell, the pomegranate.

I have to be my own tree.

Since living here on Colonsay, William has learned how to cut down a tree safely. When a tree falls, you must have the closest possible idea as to where and how it will fall. If it falls into another tree, you can only with difficulty reduce it to logs, whereas if you cut it so that it falls into a space you have already cleared, it is ready to cut up. There is also the matter of safety. A tree falls down bringing a ton weight headlong. A man working alone can be pinned and killed by a tree that will crush his ribs like those of a bird. Legislation on chainsaw work attempts to avoid this, but the chief safety is prevention. All is established by the precision of the sink-cut that must go in at forty-five degrees at the base of the chosen tree at precisely the point opposite to the direction in which you want the tree to fall.

My friend Trevor, whom I have known and respected for a generation and who is a woodsman to the ends of his branches, says that in parts of Hampshire the sink-cut is called the gob-cut. Trevor listens with such attention to trees that he would rather drive towards them than away from them. He means that he would rather be in the country than the town. In spite of this, he has sat with me in London hospital waiting rooms waiting for doctors to come and see to my various fellings. Trevor has seen it all, and his conclusion is that he would rather be outside among trees than anywhere else. He likes to read about trees. Recently, his power saw was stolen, and his toolbox. What use can those tools be to someone else? He had had that saw for twenty years and he and it had grown used to one another. He had wanted to hand that saw to his son.

This year was a big bluebell year in the woods where Trevor works. He can’t remember a year as good for bluebells. He thinks that the bluebell woods get better every year because the number of bluebell years may be melting for us all at the age we are. He does not pretend that we haven’t seen our youth away.

A tree, when it falls, brings all manner of tenants down with it. There may be birds’ nests in its branches, a marten nest in its bole, a squirrel drey in its heart, an ant city under its bark at the root, thousands of grey slaters or woodlice pouring from it, moths in chipping millions coming out like stars or dust.

If I think of my life as a tree, it is clear that I have taken, or given to myself, the gob-cut. But no one but myself is trying to fell me and I want for as long as they wish it to offer shade to my children. When I delivered that sink-cut to Fram thirteen Aprils ago, it smote him, but his roots were too strong to let go their hold and he has grown well beyond the cut and up into the canopy from where the view is clearer. His heartwood has strengthened. Arrows and longbow taken from his seasoned aim and reach hit home.

It is the last evening of the last day I am allowing myself for these eleven chapters about the year since I spoke the first part of this memoir. I intended to look clearly at why it happened, and I think I perceive two answers, one reductive and deadly and the other more open to some kind of remedial use.

I am very blind as I type this, twisting my head around in the search for sight. It does not escape me that I am twisting away, too, from the subject. In spite of being one who loves family, home, and the detail that comes with settling, what I have done is cut and run when I can extract no answer that does not involve confrontation or change. I am anxious to staunch this reaction, as I hope to curtail the delusion of self-comfort by means of suicide, in order to protect the next generation.

The way that I can see to staunch it is to see, or to try to see, and certainly to name, only what is true about it all, and not to rush from hurt into harm, or from pain into damage, since harm and damage affect those others, whom I live not to hurt or pain.

It is easier by far, I am afraid, to come to these serene-sounding conclusions living alone on an island, where little is required of me save the capacity to earn enough to pay for my keep. I need not see here, nor walk, nor have social contact, all of which are beyond me. I keep clean and live retracted like a claw within a paw.

At least I need not insist on pressing upon the thorn in the paw. At some point I may allow it to work its way out. I must not define myself around it.

Young thrush are everywhere in the garden this evening. They are slighter than their parents, no speckled waistcoat yet. They sing their hearts out in the long grass under the soft-leaved flowering sorbus that line the drive of this much adapted house in which I first found refuge over forty years ago.

It was pale strawberry-ice pink then, with white sills and window frames. Its wings wore, as they still do, mock windows that need painting in, like eyes on a blank face, like those eyes in the front of a boat I mentioned at the start of this memoir. Now the house is pale cream, its sills a pigeon grey. Or is it yellow? It depends on the rain. At its skirt where it meets the gravel of the drive along its two embracing arms and surprised central block, are still ranged hundreds of green glass floats and two cannons. At the back the house rises from a sea of planting, mainly blue flowers, agapanthus, blue poppy, aquilegia, cerinthe, iris. A magnolia and creamy roses clothe its walls.

Downstairs the bigger rooms are shuttered and cool. They are seldom in use till summer is higher, as they used to be when there were two parents and six children and me here.

The dining room and the drawing room smell of wood polish and damp, the flagged hall of stone and coal, the billiard room of leather from the brown eighteenth-century books that sit around the old half-sized table. The cues are in their clipped rack, the stained ivory balls arranged in patterns by the last children who played there. Even if you didn’t know, you would be able to tell that it was little girls rather than small boys. The colours are arranged in patterns along the cushioned table-edge, to look pretty. It’s not set up for a game, nor are the balls all scattered on the green. Girls have been here.

Or someone who has the fiction writer’s habit of making patterns out of anything at all that comes to hand.

The curving corridor-room that leads from the hall to the drawing room has changed least. It has lost the stuffed bison head and a tally of bird-sightings that used to be kept beside the wind-up telephone over the window seat. The wind-up telephone has gone and there is one that our children now think of as old fashioned as we thought the wind-up one with its separate mouthpiece shaped like the chained drinking cup from the wishing well halfway up the old drive, that has chased around its rim, DRINK YOUR FILL THEN WISH YOUR WILL. The window seat is curved, like all the fitted furniture in the embracing wooden room. The window looks out on to a lawn at whose centre rises an enormous member of the lily family that looks like a palm tree.

Under the old lairds, the McNeills, that part of the garden was laid out to look like a Victoria Cross. Things in the shape of other things, that British passion. Now the borders around the lawn are soft in the revived cottage fashion, taking advantage of the pocket of botanical shelter and comparatively hospitable soil that lies around this house. The corridor-room is rayed in its curved ribs of bookshelves with many hundreds of clothbound books set in order by various sometimes contradictory understandings of sequence. History used comfortably to crop up everywhere, while gardening took up twenty or more densely plotted and embedded shelves, the books tucked in as tight as alpines. There were rather few novels, except for Wilkie Collins and C.S. Forester. Lawrence Durrell made a flashy showing in a lower shelf. He seems for now to have made off with the gardening books. They will be coming to an arrangement in one or another bird-wallpapered bedroom in the house. Walter Scott meanwhile has settled in the billiard room.

In the shelves of the corridor-room, the spines of the cloth bindings have succumbed to the light of the Hebrides; bright hues have quietened down so that the shelves now show the muted upstanding ranks of the field of lupins, purple and cream and dim yellow and soft pink bars of opacity ranking the length of one long curve, taller than a man, measured in batons of soft colour all along the tight arrays of shelving opposite the big window.

This evening there is no one in the bigger rooms, and even were Alexander and his family here, the rooms would most likely be empty, though not devoid of living things.

The drawing room has two tall windows that look out at the same lawn as the corridor-room window, a curvaceous triple window in the vaulting Regency idiom out to the front of the house, and a double door out to the long glass-roofed loggia that is full of scented plants and surrendering wicker furniture, and a tired cushioned swing on a rusting white-painted iron frame, with a rotting canvas jalousie. There is a ceramic sink on the loggia, for washing glasses and picnic plates or cleaning flowerpots or garden shears. When you turn the tap on, the water trembles within the pipe that is conducting it long before it condescends to arrive. The pipe softly clanks. The bolts holding it to the side of the house loosen minutely.

Growing up through a window seat in the first tall window as you enter the drawing room is a tall glaucous-leaved tree poppy, romneya, with petals white like a kerchief in a portrait of a lady by Romney himself. The romneya asserts its spindly but persistent life annually through the house’s painted pebbledash skim, through its brick, through its floorboards, and into the habitual place it achieves, determinedly driven by the imperative to reproduce itself, clipped between the shutter and the cushioned window seat, on which piles of green photograph albums, recording equivalent human struggles and bloomings, lie and soften in the damp efflorescent air.

In the cupboard opposite the loggia door, drinks are kept, and an oval tray of the old silver Madeira cups that came out on the Sundays when we listened to long-playing records on the wind-powered record player, also stationery and some outlived toys. In this cupboard one recent spring, a mallard raised her brood among the envelopes and sticky labels. Did she have an accomplice, who let her out to fetch grubs for her ducklings? Did she feed off the spiders and mites and woodlice who would conquer the drawing room in a sleeping beauty’s rest time, if they weren’t shooed away from time to time? Were those ducklings raised on correspondence cards and flat Schweppes mixers?

Any precise answer rests with that duck mother and her children, so the answer will be, as it is to many things, a dry quack and no more.

We cannot always see the whole picture, after all.

It may be as well to keep a door in the mind open to whatever may alight among the paper and strong drink and forgotten toys.

Afterword

It is now mid-September. Mr Foss operated on my right leg and both eyes on 30 June. He took out the tendons from behind my knee and sewed them in beneath the skin, stitching up my eyelids to my brows, pegging my brows from stitches above them in the ‘blank’ area of my forehead, so that there is a system of artificial tension that counteracts the blepharospasm’s continual downward force and in so doing offers sight. My forehead hurts. It feels as though it is cork, with drawing pins, six of them, set circumflexwise above each eye. There are six points of pain, connected by unhappy but essential tension.

The effect is at once of wound and freeze, vulnerability and a harder surface than the subtly changing thin-skinned area around a human eye usually offers. My eyes are fat-looking, peering piggily through swollen yet not smooth crevices. They feel bruised and stiff, both the eyes themselves, weirdly, and the lids. But – I can see.

I can see.

I look broken and I look mended. I have a bodged face. I’m not complaining. I’m attempting to define. There is no eyelid and there are no fluttering delicate surfaces for another person to read. I’m unclear as to how my face is legible to anyone who sees it. Most people say reflexively that I look the same. I haven’t asked them, the same as what? There is no need for them to say that; it’s a nervous reaction, like saying one looks well when one has suddenly got fatter. The most sensible description was from a friend who said that I looked as though I’d been stitched up after a fight. Sometimes I feel as though my face has been pegged up like washing, on metal pegs, then hung, heavy, and been frozen like a dishcloth in a cold snap. My soft old face depends loosely from its new circumflexed stitches.

But I can mostly see out from it, out of it, this face on pegs. This return to a world where I can read is an unlooked-for relief, a blessing that I had not imagined would come my way. I had believed that, since blepharospasm rarely goes into remission, I was shut in the dark for good.

Sometimes, if I am tired or frightened, or if the light is bright, I clamp blind again, so I still carry my foldable white stick, though not, of course, on to aeroplanes, since it would make a plausible weapon and is therefore not allowed. I have learned that, as I’m a nervous traveller, I do tend still to go blind at railway stations and airports.

Mr Foss said that my tendons are of notably poor quality and he had to reinforce them with some synthetic strings called something like ‘Plastron’. He says that you can improve the quality of tendons by regular running. He says that running is ‘hell at the time’. It is clear he cannot lie. I still love trying to guess what he will say next.

Mr Foss said that it was ‘a pig of an operation’.

His own sport, I’ve discovered, is high-level competitive fencing.

Mr Foss is slight, and only ever to the point.

Things had got quite bad by the time I went to the hospital for this last operation. Nottingham has several hospitals including the Queen’s Medical Centre, the largest in Europe. I arrived in the morning at the small hospital on the Mansfield Road where Mr Foss had stripped out my eyelid muscles in January, having come down from Colonsay the day before. It was a journey that would not have been responsibly possible on my own, I was so blind by then, yet not an adept, since not a reconciled, nor, thanks to Mr Foss’s operation, a resigned, blind person, and was also still lame from my broken leg. William came with me on the boat to Oban and handed me to his daughter Flora at Glasgow.

She had come up that morning from Euston in order to accompany me to Nottingham. We had a number of train-changes between Glasgow and Nottingham. Flora participated in a Virgin Trains hot-meal survey. Asked to choose between Lancashire Hotpot and Chicken Curry (it was a conspicuously warm day), she asked to try both, otherwise how could it be a survey? She’s skinny and always hungry. She received a thimbleful of hummus and two small red ‘presentation tomatoes’, together with a press release more substantial than the snack itself, about moving forward into a future where the customer came first. You can see why Mediterranean travellers are baffled in Great Britain.

We crossed a lavishly green part of England after the always for me too sudden loss of Scotland.

By the time I was in the hospital, I wanted anaesthesia of thought and condition, and was, I now see, inexcusably unprofessional (is being a patient a profession?) in speaking to both Mr Foss and the anaesthetist the way I did. I asked them if they wouldn’t just let me go to sleep for good.

It was a bad thing to say. I was exhausted by my condition. Nonetheless, it was ugly. When I think of it now, I see – I see! – how things had grown in. Like ingrowing toenails, I had ingrowing eyeballs, or, more precisely, an ingrowing brain. I was doing time with my sadness, it is true, but at least I had the time to do.

Mr Foss, when I asked him, said that our lives are not ours to take, nor are those of others, and that the doors you do not, ever, open are cruelty and madness. He could have said much more.

He did not tell me what follows, but I found out later, and by accident. His great-grandfather Sigismund Stanislaw Voss, a Latvian engineer who spoke six languages, who had converted when he married his Lutheran wife, Wally, had survived the Russians but was lost to the Third Reich, which took him from his post at Massey Engineering in France and to the concentration camp at Drancy. There is no record of his fate.

The anaesthetist, when I asked if he couldn’t just knock me out, said that if anything happened to my life, his wouldn’t be worth living. Later I learned that he had recently had a heart attack and spent many weeks in hospital.

After the operation, he wrote me a detailed thoughtful response to my telling him that I had at some point been ‘aware’ during the operation. This is when the patient can hear what is going on and can think, but is unable to move (or they believe this to be so). As you will imagine, this state has a lot in common with certain nightmares of powerlessness and muffledness, when you know and see but cannot utter no matter how you strive. He questioned me closely, and sent me a number of articles on the subject. His guess was that my odd feeling might relate to my size and to my being an alcoholic. He managed to put both things tactfully. The sort of tact that must have been in demand at the Tudor court.

He said that I must warn any anaesthetist who was about to put me under at any time in the future of this incidence of ‘awareness’ (it’s a medically identified phenomenon), and he or she would increase the dose of one of the drugs involved to make sure that my brain as well as my body slept.

My sons and Fram came up for the night after the operation. I was bandaged and couldn’t see them. I am told that I annoyed them by asking about their journeys. They felt that I should be telling them my news. I didn’t really have any. I hadn’t arrived anywhere yet. I felt a bit useless. Olly had come all the way up just to see some bandaged ghoul on a gantry, probably identifiable as his mother by its bulk. He was having to go to America early the next day.

I am writing this in the beginning of autumn on a balcony beside an Italian lake, like some civilian idea of a real writer. The air is cool. There has been a Shelleyan squall. From where I am writing I can see – already the sentence is too rich in meaning to bear that meaning without my giving it an intrusive interjection for support, like the stitches holding up my stripped eyes – from where I am writing I can see a headland with growing upward out of it one quite small cypress, that seems to be gathering itself slimly for dive or flight. Its poise and pose remind me of a painted diver – the Tufa – on a wall at Paestum, in another part of this country that makes more sense to me than most.

The water is green and choppy tonight, the air just pink. Behind the headland, two long mountains meet in layers of blue. The sky is fumed with dusk as though the light weren’t going, just fainting away. On the opposite shore, the small yellow town of Bellagio disposes itself. Two campanili stand out white and will later be lit up. I know this because we have been here long enough for habits and rhythms to have laid themselves down. We shall have been here for six nights tonight.

Not only can I see, but I am recommencing to see in steady planes and charges of colour, not just the juddery reception I had when I lifted my eyes with my hands. The sort of vision that I think I have lost, unless habit makes it return, is my sharp peripheral vision that used continually to be collecting. To an irksomely upbeat degree, for one so stuck on metaphor, I can only look forward – unless I swivel my head, which aches a lot of the time, I think from the tension it generates when pushing internally against the blepharospasm that waits inside it.

Quentin arranged that we might all be together in this place at the end of the summer. It is the first summer holiday that all four of the children have ever been on together. My three haven’t been together in the summer like this for more than thirteen years.

The villa is reached by 184 steps down the sheer cliff from the swerving lakeside road. There was no such road when a group of four young Englishmen, calling themselves ‘the Lizards’, cleared the site they had clubbed together to buy in 1891 for a hundred pounds. They built a jetty, made the tall arcaded villa, established a garden and a little harbour. One of them kept a diary, which is downstairs. From it you gather the struggle and devotion required to plant and establish just one wisteria, the physical effort involved in creating this idyll on the edge of a moody body of water at the bottom of a cliff at the other side of the Simplon Pass which had not been open for that long. It’s curious, this nineteenth-century English tendency to choose to domesticate the intractable.

I feel a connection between Colonsay and this house and its situation, the close relationship with weather, the dependence upon boats, the choice of rising to physical challenge and natural beauty over other forms of indulgence, made by men of the privileged class with the world at their feet at the height of Empire and on the verge of irreversible change.

These are the last redoubts where a man could feel himself master. It is a sort of play, though it could not be further from the drawing room. It is a way of addressing otherness by not having to read or talk about it, while draining off animal spirits through considerable physical exertion. The pioneer character favours natural beauty over the created kind.

The demands made by beauty upon this house are visible through its windows and from its several balconies. All the beauty asks is that one absorb the light, which is changing all the time, dim and pearly yet full of sharp attentive spills that fall on the mountains, showing up here a grey rock, here a white church, or on the water, reaching down into it to show a lake trout hanging there in a column of revealed green, or to catch a dragonfly clipped in the air for its moment, the same size, apparently, as a single scull lying on the water moving with the smooth unbroken rhythm that looks like stillness.

In 1910 the villa was burgled. Finding it empty, the thief spent the night. He left a note, ‘Cantate anche per me’ (‘Pray for me, too’).

The older children have come from their work for the weekend. There is so much to see just now that I am staying at home at the villa. Everyone goes out in the boat to look at things. I stay at home and see things. I’ve lots of work and am still lame over distances and bad at stairs. The pearls I wear always, that Quentin gave me twenty-seven years ago and that need restringing every year or so on knotted cotton, now have the sort of fastening that is made for blind pearl-wearers, a magnetic clasp. It collects safety pins and paperclips while I sleep.

I work here for ten or so hours a day and meet the family at mealtimes and when they visit my balcony. I go rather slowly in order not to choke on my new experience of sight. It is hard to ration sight, but I am trying; I cannot yet avoid the superstitious sense that the consequence of seeing too much will be again to have my credit of sight-time withdrawn.

This July after my second operation, Fram discovered, after a lot of enquiries and effort, a priest who was also a psychiatrist whom I made an appointment to go and see. There had been some suggestion that I might start taking lithium for anxiety. Lithium is a drug whose reputation is at present enjoying a degree of rehabilitation after being thought of as quite controversial. A helpful doctor friend had identified what she called an ingrained habit of what she called ‘depersonalisation’ in me; she was right, if it means, as I think it does, a coping system of saying to oneself that nothing bad matters if it’s happening to oneself. Or, that nothing matters, since it’s happening to oneself.

She also told me that she believed more strongly every day that one never knows what is going on inside other people. It’s a sense upon which my life has been built, and which is a premise of, or a challenge to, much interesting fiction, but you seldom hear a doctor say it. Isn’t that odd?

I was willing to do almost anything to find some sort of dry land to rest on.

Most days, I walked to the chemist’s to buy new dressings and show my wound to the pharmacist. I put a gauze dressing on and then a creamy elastic long bandage that I wound round and round my thick right leg and pinned with little toothed clasps. My legs were thicker than ever, thick as waists at the knee, spongy and blue-red. Fram worried that the wound wasn’t healing and badgered me to do something more assertive. I didn’t.

The stitches were taken out of my leg. The scar was wet and about five inches long. The stitches had been neat. The stitches in my face came out in Nottingham, ten days after the operation, on 11 July. Fram took me. He and Mr Foss seemed to like each other; they were intrigued by one another’s take and speed. They had that never-questioned high-functioning intelligence in common. I turn dozy in such company but it’s the sort I like. I’m not bored; I’m listening. It’s like listening to music, not eavesdropping.

On 17 July, I went to Nottingham alone, a treat. I was already going blind again. Mr Foss had warned of this. He said that after the second operation there is often a honeymoon of twenty-four hours when the patient feels as though everything has righted itself. This honeymoon, he warned me, is misleading. I visited Mr Foss to have the first go of Botox injections which I will now have every three months for the rest of my life, if I want to see.

‘If’ I want to see? Do some people actually decide that they want to remain in the dark? Apparently, the answer to this, in any intelligent terms, is yes. We’ll come to that.

Mr Foss gave me four injections at specific points around each eye, eight featherlight poison darts in all. Any comparison with fencing is perfectly apt. He handles a syringe more lightly, more precisely, than anyone who has so far injected my eyes. Some people hurt. In their hands the needle feels wide and thick, unconfident. He was, as he always is, quick. He gave me the tiny jar of poison to take away, in case I needed topping up.

My deadly poison is still in Fram and Claudia’s freezer. How like a fairy tale. The poison that makes me see is in the coldest part of their warm home.

Minoo and I went to Edinburgh for the Book Festival for ten days. Every other day, I visited a surgery, to see about my leg, which had not healed properly, and which had put me back in the hospital for a time in Oxford. The flat we had rented was up many stone stairs.

Everything got better in Edinburgh. I was surprised by what happened to me at the Book Festival. I had felt I was there as a visitor, more than an author. Then someone got hold of the human story, the story that makes out of my whole recent experience something soppy; the ‘I once was blind, but now can see’. Which is far too simple and not true, so it will probably be what is remembered.

I hope not, though.

It is a human story. It is also a story about words. If I hadn’t been asked to write about going functionally blind for the Scottish Review of Books, The Times would not have reprinted the piece. Marion Bailey would not have read the piece nor so generously got in touch with me and told me about Mr Foss. I owe my present new-made sight to many, but directly to the Scottish Review of Books, The Times, John and Marion Bailey, and Alexander Foss.