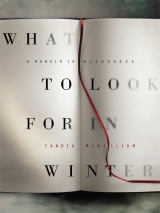

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Fram was working too hard and on too many fronts and I knew that he was often exhausted beyond endurance. I also knew – how could I not? – that there was something abnormal about my relationship with alcohol. When we entertained, I did not drink, but often disgraced myself when making the coffee. When we went out, I hardly ever drank. If I did do so, there would be a terrible script waiting just inside my larynx to tell itself. Fram would write down the awful things I said and read them to me the next day. It was like listening to another person. I had a bad person within me whom I mistakenly identified with my dead mother. What neither of us realised was the toll this was taking on Fram, not by nature immune to his mother’s melancholy.

The years rolled round and I produced my books. I lived by reviewing, which was congenial and constructive. I loved the chewiness of the process, miss it greatly in blindness. The children were flourishing. Fram had discovered a passion for being a patron of interesting architecture. Clementine disliked the boarding school she had moved on to, but, when offered the opportunity to leave it, decided entirely characteristically to stick with the devil she knew. Oliver was growing taller and taller. He played athletics and rugby for his school, in spite of his slenderness. We did not yet have a word for the clumsiness that ailed Minoo, but Minoo had a word for almost everything else.

When the three were small enough and allowed me to do it, I dressed them alike. Oliver is to this day very brave about this, though he will touch lightly on his determination never to wear quite as much pink as his mother introduced into his early sartorial exposure.

Frequently and especially at birthdays, we went to Farleigh or Quentin and Annabel came to us with their new baby Rose, an individual of early drollery and beauty. The four, apart from one short fracas when Minoo annoyed Rose at Farleigh by telling her that her bunk bed was a frigate in full sail, were as close as close.

‘It’s not,’ she said, ‘it’s a bunk.’

Something has gone wrong with my listening patterns. When first I started reading talking books, I gobbled first all my favourites and then those I’d been shy of. In that way I had, although my physical world was becoming distressingly straitened, my fictional world, or rather the worlds I was reaching through fiction; they were rich, orderly, coherent and bottomless, so that, for example, I remember a weekend of real physical discomfort and fear, but within it, telling human truths and diverting me from myself, lay The Mill on the Floss. Even through that patchy weekend, I knew that I was still I, because I could feel where George Eliot’s writing was strained, woundingly self-referential, and where it simply spilled out in its beautiful, thoughtful, human reams, as for example when the showy aunt whose name I forget shows off her hats to poor Maggie and Tom’s about-to-be-dispossessed mother.

I seem just now to have run out of reading matter, or at any rate to have lost the road I was following into the great heart of fiction. My new unities are shaken. Over this last weekend I have listened without discipline to a life of the young Stalin, to To the Lighthouse, to The Guermantes Way. I began to attempt to listen to either Hamlet or the Sonnets but the chaotic base I had stirred up for myself made this impossible and instead I seem to have made not a space for unclouded thought but a prescription for damaged sleep and violent dreams. Perhaps it is because I am so often alone that the book within which I am living at any time sets the mental weather and I can do real damage by simple accident or by running out of the steady material of genius that has the capability to crowd out my repetitively cycling thoughts.

The thing is that the steady material of genius, uninterrupted save by my own banal animal life, declares so clearly the gap between its simple exaltation and my crawling haltness. For people who read all the time, reading has a quest to it and I appear to myself, for the time being, to have lost that quest. I do not understand what patterns to make mentally with a cast of books that, although generous, is undoubtedly finite and devoid of, for example, contemporary clutter and the chitter-chatter of magazines and newspapers. I can’t look things up. I can’t reach for the tail of a memory. So much for recalling all the poetry you have ever known when you are in prison.

I must have known that the hardest part of this story to relate would be that of my marriage to and with Fram. Many of the strands that we worked at together with real happiness and perfectionism were in themselves, it is now evident, not good for us. It is only looking back that I can see that where I thought I was doing the gentle, sweet, right thing, I was in fact harming him by feeding that trait he had derived from his mother; not sadism at all, but a cool distaste for weakness. To this day I take very few breaths that are independent of thought of Fram, I take very few decisions that I do not run past the idea of his mind, I feel no experience full or ratified until I have described it to him. He is without doubt the person who knows me best in the world and has the imagination to see in me and care for the fat, pigtailed child lost in books. He is my home. I am homeless.

How does one write about a marriage? I knew what he was thinking about by looking at his face. I found him beautiful, we had countless small overlaps, plots, jokes, habits. I mourn it so much that I do not seem without it to be able to live properly, as I understand it, giving and receiving love within a moral shelter. That there were deep flaws in our marriage we accepted and grew with, like a distorted tree, and I conducted the lightning strike that cleaved us. I loved to think of us as Philemon and Baucis. But I was watering the tree from underground with alcohol and this, while Fram did everything he could to stop it and to understand it, was never as known to him as it was to me. There were the many times I got away with it and if you think you’ve got away with anything you are digging yourself a pit, most especially in a marriage. I felt that if I were thin enough and obedient enough and accepting enough, that eventually my mother-in-law would come to see that I was gentle and trustworthy and good enough for her son. The ‘surg’ might retreat, ‘surg’ being distaste in Gujarati, distaste especially in this case for too-muchness, my nimiety, Fram calls it.

In fact, of course, perhaps because of the alcohol, perhaps because the situation was irredeemable, no good behaviour was ever enough for my mother-in-law. It was probably not even what she wanted. Of course she was right to feel that I was meretricious, because I was changing shape to suit her.

My steadying father-in-law died suddenly on Jersey in the winter of 1992 and Fram flew to be with his mother and sister. On his return after the funeral, he lay on our bed and recounted with clarity the wrapping of his father’s body in white cloth, the holding steady of the chin with a band of white gauze and the days before the funeral during which my father-in-law seemed to exude a sweet scent. I could not have loved Fram more. I still today could not love him more. I love him more every day, as I do my children; it is a growing conversation.

Yet what cracked it? My insistence on surface perfection and my falling far from it? His insistence on surface perfection and my falling even further from that? Our tight closeness? I do not think that our marriage was airless and certainly we had many friends. I have far fewer now. Aloneness and blindness have seen to that. Fram built a beautiful and painterly garden, filled with striped roses, tree peonies and a special tree for the birth of Minoo. Indoors we had made an elegant flat, deeply inhabited by the spirit and works of his mother though it undoubtedly was. I liked that, solicited much of it. The thing is, I thought that I was helping my husband by going along with what his mother wanted of him, and in this I could not eventually have been more wrong.

So it was that I never fussed when my mother-in-law needed Fram at weekends or didn’t include me in family matters. I understood completely that it was cosier for them to speak Gujarati on the telephone as well as being more discreet. I understood very well that it was I that was being excluded and I went along with that because I believed absolutely fundamentally in my own exclusion. I did not think I deserved a place at the table. I was a servant and not a very accomplished one, when it came to comparisons, at that. I suppose that I added to my own distaste for myself that of my now widowed mother-in-law who needed nothing more than her children at her side, and if one of those children were married, well, it was to me, who made a very good job of dismissing my own self. I rubbed myself out.

A healthy person would see that this was the very opposite of what everyone involved might require. During our marriage, I had three novels in my mind whose long period of gestation I was moving through. One, set in a hunting lodge in the Czech Republic, was about children, power and loneliness. It will never get written. One was to be about the consolatory and diverting place that a wife’s girlfriends play in a marriage. I didn’t subscribe to the Anita Brookner theory that no woman is loyal to other women when it comes to men, and I still don’t; though I do believe that female institutions are nastier than male ones, very possibly on account of something like the Brookner-drag. The third novel, which perhaps I now may write since I have at hand what I never thought I would have, its termination, was to be about marriage, specifically about the happiness in marriage that is so far deeper than any I, at least, have found outside it.

Autumns were always difficult for Fram throughout our marriage. Not only was it the new academic year, but I would almost invariably, at some point around Remembrance Sunday or All Souls, get very drunk, mourning, or that was how I excused myself to myself, my dead. The boringness, the repetition of being married to an alcoholic and its frighteningness, are inexaggerable. Yet we went through long periods when I absolutely didn’t drink and we felt unclouded. A logical person, a non-alcoholic, would say, ‘Well then, don’t drink.’ But drink isn’t like that. It tells you it won’t hurt you and then it steals your love. One of these autumns, after both our fathers were dead, I dreamed that we were divorcing. It seems to me now that I fell on the floor. I felt like carcasses, hung upside down from their feet, split through, revealing all the purple and green and webbed gut and chipped ribbing within. I was not just one carcass, I was many. Fram comforted me and we went back to sleeping like spoons, which was how we slept. All along, throughout our marriage that was to me an intensely, intrinsically romantic one, where the romance lies in the heart of the marriage, not in assumed behaviour, Fram, who is rational, had said, ‘We can never know the future. One of us may fall in love with someone else. It’s more likely to be you.’ I could not imagine anyone who answered my internal mental and spiritual detail as he did. I still cannot. Nonetheless it happened, and he was right and here I am now living my life, thirteen years after leaving Fram, still married to him and fortunate enough to be, as his new companion Claudia, says, ‘His widow. You’re his widow. But you’re lucky because he’s still alive.’ What led us from there in our marriage, that several shrinks said was too close and we scoffed, to here?

It is hurtful but may be true that what led me here was nothing more, nor less, than alcoholism. I could not have behaved as I did behave had I not been, in addition to being unhappy, at a point in our marriage when Fram was intensely preoccupied with work, drunk. The children were fourteen, twelve and seven. I am a person who cannot bear mess, who is deeply invested in doing my best to be kind to other people at all times and who loves her children pre-eminently. I am a conventional woman and was at that juncture in my life not unhappy so much as caught in a web of behaviour that bewildered me and that I was not clear-sighted enough to see my way out of. So I hid from myself that I felt any resentment or pain at my unnatural obedience to my mother-in-law, because I really believed I was doing the right thing. Nonetheless, I left my marriage at the urging of someone I hardly knew who knew less than nothing about me.

Fuss is made about turning forty, particularly if you are female. People start muttering about hormone replacement therapy and diminishing quantities of eggs. In this last area of concern, I couldn’t have been gifted with a more imaginative present than that which I received, driven over in person from Herefordshire, from my step-aunt Nicola Jannink. By then personal assistant and more to the head of an international security firm, Nicola was a compoundedly confident character. She parked her sporty roadster in the always rather controversial car park with allocated spaces in front of our flats, and pressed the doorbell, arriving unannounced on my fortieth birthday for which I had invited twelve friends to lunch. I was making complicated vegetable mousses in the shape of lobsters and was already attired in the size twelve knock-off of a Jasper Conran that came out on these occasions. We saw and did not recognise Nicola on the entryphone camera, but of course her voice was characteristic. I was at once aware that I could not invite her to lunch and that it was approximately quarter to one. I was going to have to be rude.

Luckily, she, according to some ways that one might interpret it, got in first. She entered our drawing room, which we had been titivating and filling with flowers, with a very large box, perhaps a yard wide and a foot deep. From it there came a smell that combined every single pong that makes you want to chuck. It was not a question of a light whiff of white truffle, or a little farmyard on her boots. It was everything that no Parsi – no, no person—would want in their house. She put my scented gift down on our sofa, which, as it happens, was cream. I looked into the box, expecting to find I really was not sure what but at the very least telly-dinner for Grendel. Within the box was my name, ‘Candy’, beautifully spelled out in many varieties of birds’ eggs, from pheasant to goose to duck to Canada goose to hen to bantam to quail. So long must it have taken her to collate her generous gift, which comprised exactly forty eggs, that not all of them were barn-fresh. With them went a card that I opened to spread further this unique moment of coming of age. The card read, ‘To Candy and her various children by different men, happy fortieth birthday.’

I think I left it to Fram, to whom that sort of thing comes naturally, to be clear, or at least so polite as to get rid of her, while I in my party dress took my ovarian future down to the furthest end of the garden, trying hard not to break any more eggs.

The day extended and no further social eggs broke, so that for once, I believe, I did not even get shaky or high or any of the infinite gradations of drunk that were legible to me and my poor husband who, by nature vigilant, was rendered hyperactively so by having to thole my hidden but evident alcoholism over those first ten years. And there was that one other thing hiding inside us, we two who were one, of which we were ignorant.

LENS II: Chapter 9

Sonnet CX

Alas! ’tis true, I have gone here and there,

And made my self a motley to the view,

Gor’d mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offences of affections new;

Most true it is, that I have look’d on truth

Askance and strangely; but, by all above,

These blenches gave my heart another youth,

And worse essays prov’d thee my best of love.

Now all is done, have what shall have no end:

Mine appetite I never more will grind

On newer proof, to try an older friend,

A god in love, to whom I am confin’d.

Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best,

Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.

Perhaps I was at such a pitch of alcoholism, though I had kept it so well hidden, that Mark Fisher might have been anyone; he deserves a better life than the one I was not by any means sharing with him. Anyway it read more like a play than like a life, from this point on, for several years. The plays change in my mind but in the main it is A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

For the first two years I made an ass of myself, dislocated my children’s lives and misled another man as well as breaking Fram’s heart. When told the news, Minoo, brought up on Narnia, said to Fram, ‘It is all right for me because Mummy still loves me, but for you the golden chain is broken!’ He was seven. He held to the faith that it was not actually so, and he has been, a decade later, proven correct. For perhaps the next three years, I lived in a way that is familiar to anyone who lives on the streets. The only way that I can atone to my children for this is by never going near a drink again.

When I was alone, I simply drank, and I drank whatever I could get. This included household cleansers, disinfectant, a substance called Easy-Iron that lends smoothness to laundry but is not a smooth drink. I arranged to be alone as often as possible because I was so ashamed.

When you begin to drink, if you are a ‘normal’ person, you receive a faint heightenedness and a sense of confidence and permission. Very soon, and I do not know how, I realised that alcohol was my false friend; I think I knew it by my first term at university, but I chose to deny this to myself. I knew it changed me.

Alcohol utterly transforms my character. Very briefly, it used to give me a window of beauty and connection to that beauty, when I would see nature, people, children, all, as it might be, heightened in their own, as I thought, glow. I suppose it was nothing more aesthetically grand than having a sort of Martini-ad director inside my brain. During the years after I left Fram and was drinking, I must have humiliated Mark countless times and I am dead certain that I scared my children. How can a woman who has found her own mother out cold, actually dead, pass on to her beloved children the same experience in all but actual fact?

You can spot other middle-class alcoholics just as you might spot someone who belonged to the Masons. There are the big signs, such as being there before the Co-op opens, which it does, conveniently for alcoholics, at six in the morning, and the small signs, such as being far too polite and explaining exactly why, as you hand over the precise change in 1ps, you need a ready-made gin and tonic at nine in the morning. You learn to spread your custom thinly, so that the people who run Oddbins, Threshers, etc. won’t know that you are an alcoholic, when your every gesture tells them as clearly as though you were wearing the T-shirt. Alcoholics know a good deal of secret information and will in any town be able to find the corner shop that does sell booze. Under my belt are Aberdeen, Middlesbrough, Wick, Cromarty, many districts of Edinburgh and Glasgow, Inverness, a comprehensive guide to Oxford and absolutely no experience of where to get drink in London at all, although I do buy it online for my friends and my children. That gives me not a pusher’s pleasure, but answers the old need to feel connected to what is normal.

The rules by which alcohol makes you live are the instructions in how to live as though you were dead. Alcohol tells you not to answer the telephone, not to answer the door, not to open the curtains, not to eat, not to wash, not to clean your environment and to cover all mirrors as though after a death. Alcohol tells you to wear black and not to clean your teeth because your toothbrush will make you vomit. Alcohol tells you that you need a drink at four in the morning. It then tells you that you need to sick up that drink to get the way clear for the next drink. You obey it and you sick up blood. In the end your ears, nose, eyes and mouth are streaming blood. You shit blood. You piss blood.

I used to be visited by a bloke called Gary, who represented himself as being an ex-miner. He sold dusters, mops, oven-cleaner and the like, all smelling strongly of cigarettes. Every year of the ten or so I lived in my Oxford house, at the end of the cul-de-sac, Gary visited. In my, perhaps, fourth year of residence, he said, as I passed him a tenner, ‘God, m’lady, you look bad. I’ve never seen you look so rough.’ Oddly, I realised only a month ago that the honorific title was a tic widely used by Gary’s brethren. Sober now, but quite as jumpy about the front-door bell, I picked up the entryphone here in London, at Tite Street, to be greeted by:

‘Hello m’lady, it’s Gary. You know, dusters, ex-miner.’

I don’t think it was the same Gary and I’m not capable of seeing single, let alone double, but I was struck by the usage. The only other place where women are routinely addressed as ‘m’lady’ is, in my experience, Wiltons restaurant in Jermyn Street.

‘Hello, big girl, who are you married to at the moment?’ Peculiarly enough, I have been asked this question twice in my life and I take it ill. I forgive the first enquirer, who was drunk himself, unhappy and shy. He is now dry, handsome as all get out and back to his delightful manner that I’ve known since I was newly wed to Quentin. The other person should have known better. The occasion was a cocktail party for my older not-sister Jane’s fiftieth birthday at Leighton House. Actually I like the man who asked the question; he is interesting and uses his fortune to good ends. Nonetheless, I explained to him why I did not want to be called ‘big girl’, even if I am one, and I could not credit his having reached over fifty without realising that women are unfond of the insult direct, let alone the implication that one shags like a stoat and marries frivolously. Evidently my voice was carrying, which was very lucky as the party was full of family, their voices raised in euphonious competition. One of the many pretty cousins called Kiloran, this one a whip of courage and loyalty, was bouncing up and down. She is tiny, very sexy and has a lisp. ‘Thatth’s it, Claude, thatth’s it. You’ve toughened up at lathst.’ Not in fact.

Speaking of toughening up, there is one, slightly solemn, point that I’d like to make about AA. Of course I love it and owe my sobriety, ergo my life, to it, but it cannot but be observable that as an institution it is, and I’m not complaining, made for men. The systems whereby it strips down the ego and squashes, filtrates and cleanses the superego are all very well for people who think a great deal of themselves in the first place. I know that I drank from fear and shame and I have heard the same from many other women. Fear of what? Of comprehensively everything, mainly of how and who to be. And shame? Well, you are a woman and to be a woman alcoholic is to be born to shame, which makes a fine foundation for the Rapunzel’s tower of shame that will grow up on it as the woman drinker lives her eremitic life, and lets that lovely hair get so filthy she could never plait it to make a rope and escape from her tower of shameful habit. Her habit has become her habitat.

There is a point in alcoholism from which you cannot be brought back. This point is referred to by the nickname ‘wet-brain’. When people have wet-brain they are simply gone and are allowed by the defeated carers, medical and familial, whatever spirit it is they wish to kill themselves with, since the only way is down.

I do not know why it is but the feet, that are so rich in nerve endings, are tremendously vulnerable to alcohol, increasing in size, turning blue, cracking, exuding pus, losing nails, prone to ulceration. At one point, it looked as though my left foot was going to have to come off. I may say that my family spotted my alcoholism long before my GP did and it was Quentin and Annabel and the children, with poor Mark Fisher, who at last confronted me, collected me, cherished me and delivered me to Clouds, a rehabilitation centre near Shaftesbury, about which and whose late inhabitants, I had, long before, written that architectural-cum-social review. Clouds was, with Taplow Court and Wilsford, the lost house that V.S. Naipaul describes so beautifully in The Enigma of Arrival, the residence of a family who were part of that poetic grouping known as the Souls.

Since I had, amateurishly and alone, attempted all the usual separation between myself and alcohol – not drinking at all by using willpower, only drinking one glass and that glass being Champagne/red wine/vodka/alcohol-free lager/White Lightning/Benylin, and so on and so forth ad infinitum or more properly ad nauseam, I knew that I had to ask another person to help me. I was enormously lucky in that, given my incapacity to take initiatives, except disastrous ones, my family, that is Quentin and Annabel and the children, did so. I was literally too drunk to notice that Fram had a hand in it too.

For some reason I had never been to a multiplex cinema and on the fourth or fifth day of being dried out in Hampshire, it was decided that Rose, her friend Viola and their mothers and I would go and watch Shrek at the Basingstoke multiplex. I was, from the first moment, certain that someone would arrest me for being with normal people. Rose then ordered a medium-sized popcorn and I knew that I was very unwell indeed. A thing the size of a filing cabinet was placed in Rose’s slender arms. I asked the person behind the counter what large looked like and there passed across his features the terrible boredom of having to explain things in the real world to leftovers from the dusty old world. We sat in ogre-seats, each the size of a small car. I had Rose next to me who explained to me the quotations from other, classic, movies. Later in the day Rose was kind enough to opine, ‘I think you’re getting better, Claude.’ At that stage in her life her voice was very much like that of the Queen. Her part in my recovery is inexpressible because that child put her trust in me.

Of course no alcoholic is being honest if he or she denies that there were those radiant moments of connection with what felt like the truth and a clean vision deep down into it. William James catches it in The Varieties of Religious Experience:

The next step into mystical states carries us into a realm that public opinion and ethical philosophy have long-since branded as pathological, though private practice and certain lyric strains of poetry seem still to bear witness to its ideality. I refer to the consciousness produced by intoxicants and anaesthetics, especially by alcohol. The sway of alcohol over mankind is unquestionably due to its power to stimulate the mystical faculties of human nature, usually crushed to earth by the cold facts and dry criticisms of the sober hour. Sobriety diminishes, discriminates, and says no; drunkenness expands, unites and says yes. It is, in fact, the great exciter of the yes faculty in man. It brings its votary from the chill periphery of things to the radiant core. It makes him for the moment one with truth. Not through mere perversity do men run after it. To the poor and the unlettered it stands in the place of symphony concerts and of literature; and it is part of the deeper mystery and tragedy of life that whiffs and gleams of something that we immediately recognise as excellent should be vouchsafed to so many of us only in the fleeting earlier phases of what, in its totality, is so degrading a poisoning.

When I was about thirty-two I went on a book programme with Allan Massie and P.D. James in Glasgow; it was for telly, and I’m scared stiff of that. Each was asked to recommend a favourite book. I had just finished reading The Drinker by Hans Fallada. If I had obeyed it, I should not have had to live it to its dregs. It is the stony truth about drink for those who have alcoholism as I have it. It takes genius to write of altered states and how they feel, so that the sober reader may enter the state he has very probably never known. Are such passages ever written by non-alcoholics? One thinks of the writers of such sustained and convincing accounts as The Lost Weekend or Under the Volcano.

I wake up quite often in the night in white dread. Drunks are prone to what are called ‘drinking dreams’. One of my worst drinking dreams reproduces an evening at a private house in Smith Square at which I entertained Simon Sebag-Montefiore and John Stefanidis on Simon’s Anglicanism. He is, of course, a Jew. Neither of these men is crazy about fat mad enormous noisy women; they are used to the most groomed, elegant and pliant women the world may offer. The relief on waking to discover that at my bedside are no bottles of red wine, none of vodka, not a trail of sick, and no blood in the bed is great. I have as many gaucheries, madnesses and fugues as any other drunk. When I hear of some shit who has taken advantage of this looseness in my memory and suggested that we may have been intimate, I add it to my files. You will recall St Elizabeth who, when asked what she had in her basket by a superior who was growing weary of her good deeds, replied, ‘Only roses’, though in fact she was bearing bread rolls to distribute among the poor. So once, caught terribly short on Lexington Avenue, very late at night and unable to find the keys of my sweet old-fashioned hosts, I peed into my Accessorize evening bag. No trace at all in the morning; a miracle. The great thing I mind about having been drunk is the imprecision and boringness that descend and, should one sink further, the self-pity that is the worst of self, in the guise of a lament and in my case, at any rate, a keening for all the dead and all the living who will be dead.