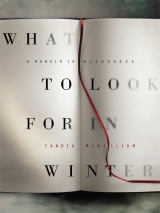

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Chapter 6: Goosey, Goosey Gander

Goosey, Goosey Gander,

Whither shall I wander?

Upstairs and downstairs,

And in my lady’s chamber.

There I met an old man

Who would not say his prayers,

Took him by his left leg

And threw him down the stairs.

My computer has just offered to me, within its menu of formatting, the information that ‘Widow/orphan control’ is already in place. This means that no lone word will be left to stand unprotected by the words with which it has been conjoined, or with which it has grown up on to the page.

When I worked at Vogue, laying out copy, we hunted these widows with our scalpels, taking out antecedent text in order to bring the widowed word up into a warm paragraph away from the cold of white space.

Today the weather on Colonsay is so clear so calm so bright that I am afraid to use it up by mentioning it. I feel that by staying indoors in my apron trying to catch words and put them down, I am buying a day in the sun for someone else. If I have a dark indoor day, will that not equalise things somewhere? Won’t the weather keep itself for the weekend, when we have our sister Caroline visiting, and Katie’s daughter Hannah and a pair of newly married friends, Rupert and Ellis?

If you fly an aeroplane, you cannot think in such ways. You read for what is actually going on. You do not navigate by magic. Alexander reads bodies of water, for the direction of their spume, the energy of their choppiness. If the loch that is full of brown trout is spilling over its dam on to the traces of the old road, he knows that the ferry will not be able to get into the harbour. He lands his small plane no distance from meadows where corncrakes nest and ragwort grows, the one a protected, the other a notifiable, species. He can’t make provisional bargains such as mine with nature. His life, and the lives of those whom he flies, depend upon his reading its actual intent from its present state. Before the tsunami of Boxing Day 2006 struck, a teenaged girl who had learned in her geography class that, if the sea suddenly sucks in its breath so that beach is exposed where it has not been before, there is going to be a great tidal wave, ran about a beach in Sri Lanka, telling people to run for their lives.

Would you obey such a command? Some did, and escaped with their lives. She cannot have had time to explain her urgent order. Her listeners must simply have trusted and acted in the same breath. Knowledge gave her authority.

What interrupted her holiday distraction sufficiently to persuade her that the sea was holding its breath before it roared inland for devastating miles? There must have been a sound, or a silence, some sea change; possibly a melancholy long withdrawing roar. Or did she see the bed of the sea, exposed and appallingly dry, every bit of water sucked back into itself to reinforce the giant wave?

That girl was doing what we are told is the only way to live, now that an afterlife is all but discounted by rationalists, that is to live in the moment. Her moment gave what must have felt like an afterlife to those who survived.

Who, fully conscious, lives in the moment, actually? I have met some who think they do, or even appear to. The first are often intolerably selfish, the second usually very old and of apparently high principle, or very young indeed.

But can we know that even infants really do live in the moment? Anyone who has looked into the eyes of a baby knows that its soul is preoccupied. Those who try to live in the moment fail, since consciousness of the attempt occludes the purity of its essence. It is far easier to accept existential discomfort and accommodate oneself to it than to live existentially.

Aren’t we more like the goose in the nursery rhyme, wandering upstairs and downstairs and from room to room in a house we cannot envisage as a whole?

Although Fram thinks of me as that sleepy lion, it is the goose who has lately predominated, and he would, when exasperated, call me a goose. In plenty of ways he is right. Like a goose, I hatched and fixed upon him, making of him my parents as well as a focus for my thoughts and days, just as a gosling will, of whoever brings its enclosing egg to term.

Like a goose, I would be rewarding to render down to fat, like a goose I hiss if my idea of home is attacked. I panic in advance just as did the Roman geese sacred to Juno, herself an intensely feminine and domestically petty older goddess, who suffered from jealousy incidentally, and was, while we are about it, unattractively insecure about her appearance. Also, like a goose, at the moment, and this is where the rest of the nursery rhyme comes in, I waddle.

And ‘gander’ is a word for a verb of looking, in which English is demonstrating to me its richness the less I am able to see. In English slang, to ‘have a gander’ is to take a look.

Last autumn, I moved from the upstairs flat in Tite Street to my older son’s house, still in London. He was twenty-six at the time, with a demanding job, a girlfriend and a busy social life. He moved out of his own room for me and put himself in the small spare room which he had previously rented to a nice, very tidy, girl lodger. He is six foot six and a bit tall, and very tidy himself.

He opened his house to me and my clutter, my too many grey cardigans and my unnecessarily growing number of books, my large out-of-date CD player, the clattering heaps of talking books, my stocks of ballet pumps in silly colours, my eighteenth-century Scots-Napoleonic child’s chair that I have had since I was two, and my chunk of lettered stone – the design for my father’s grave – my fading watercolours of fish, executed in Macao by a painter, ‘almost certainly of Chinese origin’, and my painting in oils of a jug of pink roses made by Henry Lamb for my grandfather Ormiston Galloway Edgar McWilliam. The piece of funerary inscription says UTILITAS incised in grey Scots stone. Usefulness is one of the three essentials for architecture, according to Vitruvius. The others are FIRMITAS, strength, VENUSTAS, beauty. My father had these characteristics. The stone in the Flodden Wall of Scottish Heroes declares them together with his span 1928–1989.

My son has a thin television. His ironing is immaculate. He looks new. Even when I was more presentable, the way I look did not come naturally into his view of the world. No sooner had I begun to live in his house than it started filling up. He does not like stuff. His tolerance of my way of being has been gentle.

It’s more graceful than tolerance in fact. He has twice alluded to something he has called ‘homeliness’ starting to happen in his house. But I don’t think that he is being satirical. He is never snide. His face was open when he used the term.

It was a fine day further on into the autumn, and I had a doctor’s appointment. I decided to make an effort with my goosey appearance. It was a grey jumper I lit upon, instead, for once, of a cardigan, and black skirt and ballet pumps. I was running not as punctually as usual. My son’s house is arranged around a steep but solid staircase, fitly carpeted, firmly banistered.

I keep my white sticks in a bowl by the stove, like the utensils they are. My mobile telephone was charging by my bed upstairs in my womanish bedroom; no old man, reluctant or not to pray, was up there in my lady’s chamber. I was on the last flight down stairs when I fell in a way that struck me as new, and then as very new.

I saw what I was made of, clearly. Two white bones stuck out through the now surprisingly blue and white skin of my left leg. There was something pinkish like veal.

I remembered what my friend Robert had done when he had a stroke years before, as a young man. He took over twenty-four hours to do it, but he rolled and dragged his literally half-dead body to reach the telephone. Now, Robert was even taller than I, and in worse trouble, and telephones were immobile in those days, so I was lucky. These were my first thoughts.

I remembered that my son wouldn’t be home for two days. I vehemently wanted to get out of this pickle before two days had passed as I did not want Oliver to find me broken and filling his front hall in a spill of handbag contents. I had resolved that he must never again find me wrecked.

I did pray then, simply and aloud. Praying for oneself is discouraged by every friend I have who is serious about prayer. I prayed for something I lack, whose lack has contributed to Fram calling me a goose. I asked my guardian angel to tune me in to the frequency some people are on all the time, common sense.

I was apparently stuck. It must only be apparent. I thought. I made three steps upstairs on my bottom and arms, backwards, towards the mobile telephone plugged into the wall two flights up, and saw that I was already late for my doctor’s appointment that had before I fell been due in an hour and forty minutes. I thought that it would be a bore to pass out.

It might also be quite pleasant to pass out if I was going to spend forty-eight hours alone with my odd leg.

What was wrong with it?

The foot was pointing the other way. It was pointing backwards. I took it in both my hands, pulled my foot away from its leg and did my best to turn it round, so that the toes would point forwards. Nothing hurt because I held all my thinking away from my left leg. I cut off its messages.

It was the look of the thing I didn’t like, so that proved that my trusty body, just as when I had my fit, was allowing me my eyes now that I was, in anatomical equipment terms, a leg down.

I was apprehensive about my family. They would not like this.

I thought of Robert, inching towards that telephone years ago to call his mum. I asked my mother for help. I neither cried nor shouted.

Not many people are around in the day in a small London street.

I was going to have to risk embarrassment. I did not want to shout. Noise makes me panic. It is seldom necessary.

I could go no further up the stairs. The line of least resistance exerted its to me inexorable sway and I was, not soon, but at some point after taking the decision to do so, making some sort of progress back down the stairs and towards the front hall.

Both Oliver and I had heard what may have been an urban myth about fishing rods with magnets on the end used to burgle the houses of people of methodical habit who keep keys close to the front door. We fondly feel we have another method.

I lock myself in when I am alone, almost automatically, having for over a decade before I moved to London lived next to an individual of whom I was afraid.

That once prudent habit might be, if not the death of me, a nuisance now, I reflected.

My son likes big umbrellas. I saw one, hanging behind my untidily many voluminous coats on that gloriously orderly boy’s coat hooks in his front hall.

I prayed again, this time for as much stretch as I had had before I began to fall in towards myself, for my young stretch that had fled only in the last pair of years.

I reached Oliver’s umbrella. I wasn’t in pain, but I was high as a kite, observant in the way I am when in a chemically altered state. If only I didn’t have to fall down in a fit or break myself to get my eyesight back at its former pitch and heightenedness.

Oliver’s umbrella was naturally perfectly furled. He is a man of action who understands the importance of small things. He is the man who stows the parachute correctly every time.

I held the ferrule of the umbrella and moved its hook towards the door, not hopeful, but trying to implement the care of a burglar with his fishing rod, the other way about.

My earlier inattention to detail might just be going to save me from my flying slipshod fall, for I had not closed the front door on its intractable deadlock as I think that I almost always do.

I opened the front door, which was one astounding stroke of luck.

I began, quietly and not convincingly, to say, ‘Is any one around?’

I had grown used to hearing no one pass the windows of the house in the day except to set off for work or come back. It was late lunchtime.

I did not want my upsetting left leg to be visible, were anyone to come. I tried to bend my knee back and conceal my shattered ankle within my black skirt with stars in its weave.

I’d not noticed the stars before.

I was seeing stars, like in a comic. I missed having someone to tell my thoughts to.

It was bright sun outside, low autumn sun.

I saw two angels, male of course as angels may be, one shorter than the other.

It was two weeks since the crash in the markets of 18 September 2008.

My rescuers had the sort of manners that occur only in romances. One was Greek, the other German.

When the paramedic who was driving turned on the siren of the ambulance in which I found myself I remembered that I’d been in the hands of these vigilant kind people before. They put a line in me and started with the morphine, managing at the same time to talk soothingly and to obey the bureaucracy that surrounds the administration of Class A drugs, while listening to my chief worry, which was that Oliver might find his house imperfectly tidy. They talked down their radios into the emergency bay.

It was the same hospital.

I had dreaded that.

The hospital had become my place of fear of dying alone.

Hospital had been till that fit the place where the children had been born. I was that lucky a woman.

Now, though, I belonged to that major part of the population whose knowledge lay with their fear; that it is our modern lot to die away from home and away from those we love.

In some ways, though, this was like another place, so different was the atmosphere of this ward from that of the first ward where I had lain with the silent doctor quietly dying and opposite the stark shrieking old woman reduced to open bowels and mouth.

It was during the following days and nights that I discovered that I do not get on with morphine, which I had been keeping as a treat for the rainy day when an addict knows her number is up and so she can accept pain relief without fear of dependency.

Morphine makes me itchy. Junkies often scratch, I remembered now, from gatherings I used to attend under the shared delusion that we were at a party, when gear was another way to spend money with nothing good to show for it. Not, ever, my bag. Too scared, too broke, too oral.

This time the dying old woman on the ward had a name that was lovingly used.

I was barely coherent and about to be taken to the operating table (the surgeons work all night in that place) when one of the angels arrived with orange roses in his hand, ‘For the lovely Mrs Dinshaw’. People remember their first kiss. I will remember my last gallant bunch, and that courtly untruthful adjective. This was not flirtation. It was the completion of a certain form of gentle behaviour. What flowers these were, a disinterested, foreign, correct bouquet. I felt as fortunate as a researcher coming upon an unknown primary source.

Hospital gowns are made for people of average size. I had hardly been so unlovely, immodest in my gown, spotty with opioids, haywire with anxiety about the children. I asked him to put the flowers so they were for all of us women in that ward, in a jar on the ledge of the big window where pigeons panicked, settled, tapped with their bills on the other side of the glass through which lay London.

It is such things as my rescue by the two angels that make me in life believe more in E. M. Forster’s and Elizabeth Bowen’s sort of plot, that intersperses literally incredible melodrama with lulls where the shifts are apparently minimal, rather than in the steady organised tempo offered by more evenly plotted novels. Elizabeth Bowen says this in her notes on writing a novel: ‘Chance is better than choice, it is more lordly. Chance is God. Choice is man.’

I’d say, chance is fiction at the top of its reach, choice is comfort reading.

Tolstoy feels like life, as you read him, with all the never irrelevant extraneousness, and the fullness of it all. But life, to me, seldom is Tolstoy. He improves on it, at any rate, for this reader. To read him is more fully and steadily to live. One calms down, daring to be tranquil within his fields of power. He is like life, if we were fully able to remember it outside the bias of our own temperament.

The ward was full. It contained only women, six of us. We might have been the cast of a soap opera, so neatly did we fill all the roles. Everyone was really quite ill, which achieved an unusual thing. Instead of sinking into solitariness and dislike, we looked after one another. The two youngest were particularly gentle. Each was gravely ill, one a blonde firecracker whose lover had killed himself exactly a year before and who was experiencing bouts of unidentifiable but excruciating pain, and one a young mother whose jaundice made her skin Vaseline yellow against her dark hair. She had a proper bust and lovely ankles and wrists and her whole family, mum, dad, husband and two little boys with crew cuts came in to watch telly with her in the evenings. Her father-in-law had been murdered in west Fulham the year before. ‘Bastard said it was for his jacket,’ she said. ‘Leather.’ Her eyes filled up as she spoke. Heart matched well-screwed-on head.

There was the other faintly shaggy person like me, an artistic and witty woman who raised her young grandson herself and had undergone a terribly botched operation, and whose ex-husband was slowly dying in a hospice near the hospital. There was the nice Chelsea widow lady who was afraid to go home and whose signal gallantry took the form of grooming. At all times, Betty’s hair was perfect.

And in the corner there was Ethel. Ethel was very old, and terrified. She whimpered like a dog and moaned horribly and regularly. Her guts made awful noises. She stank of shit unless her nappy was changed, because she had bad diarrhoea. She fiddled all night with her catheter and cried out at the sharp pain. You could tell the type of pain by the outraged hymeneal cry. All night she did it, sleeping sometimes by day. She was lost and wretched and might have been ignored or sighed at by these other sick women.

It was the young ones who took the lead, the opposite of a pack turning on the weak.

Each of these young women had herself a lot to bear. Each was seriously ill, without knowing what that illness might be. The blonde, who put on her extra eyelashes daily and always looked a treat, had a mother in the last stages of Alzheimer’s. On about my fifth night in hospital, the dark young woman received a message from her husband, who worked in a timber yard. A load had fallen on to him. He was in hospital with a cracked skull. She slipped out of our hospital, coat over gown, and went to see him in his hospital. By then our nurses loved her. They made no fuss when she returned.

‘I give ’im a piece of my mind,’ she said. Lucky man. She was a clever girl.

She was what tabloid papers call ‘a fighter’. Things were clear in her head. She was affectionate, brusque, tender, direct.

We were nursed with discipline, which feels good when you are that sick. There was little unkindness, unlike on the first ward. Agency nurses caused real tensions, about pay and about relationships with patients. They may not have intended to do this, but it made the staff belonging to the hospital sore. They were jumped by absence of warning and by different nursing techniques. Agency nurses also earn more. I heard not one mention of this. It was the style of nursing that was the chafe. We patients unionised if there was a sense that Ethel wasn’t being properly cared for. She was, being lost in her mind, demanding. If a nurse couldn’t come to her, one of the beauties held her hand and kissed and soothed her, just as though she were one of their own. Ethel was in hospital, she was demented, and afraid, but she wasn’t alone. It was a delicately managed thing, and took grace on the part of the nurses. They were fussy about hand hygiene and they shooed the girls to their own beds to rest. What kept the whole strained and frightening place from driving us into our lost selves was simply human connection.

I was blind and on a Zimmer, so they directed me as though I was driving a dodgem when I was allowed my first trip to the bathroom to go and wash. The bathroom was shared with men, who were quite as bothered by bumping into women half naked themselves as we were at being seen unwomanned. When first I was washed down with mean soap and an institutional paper towel, I felt remade by pampering luxury. It is hard to find yourself in dirt. You find yourself in water, or in being clean. Cleanliness is next to some exaltation if not godliness.

The nurses would shout across beds while they made them about why their parts of Africa were best. There was tough barracking and teasing. The main hero was Jesus. Very often in the night, a nurse would praise his name, or thank him. I wondered whether the two Muslim nurses seemed left out. It did not feel as though the deities were in battle. They were each so desperately required.

We were there long enough for a shimmer to go around the ward, a shimmer of secret delight when we were allowed to know that the pretty staff nurse was expecting her first baby. We began to mother and boss her.

The blonde beauty had many visitors, pretty girls and elegant men bringing gifts from the shops they worked in.

Ethel turned some corner into serenity. We discovered that she loved sweet things and would smile and babble like a little girl if you gave her soft sweeties. There was consternation that she might be going to have to enter a home, in effect to die. She had a daughter, but she couldn’t remember this. An equal heartbreak. She had a voice as rough as a herring-wife from my childhood. It was lovely to hear her when her shouted news from wherever she was sounded happy.

‘Aw, Vat’s laaavely,’ she would yell while she was washed down after having her nappy changed. ‘Vat’s laavely. Aintcher good ter me?’

I couldn’t go home to Oliver’s house. I was now a person who couldn’t walk, as well as one who could not see. My eyes had shut down again when the blind panic of adrenalin ceased. My blind panic, so it seems, gives me sight.

In hospital, I had received flowers from my agent.

This was both to say, ‘Well, you are in hospital again’ and to mark the broadcast of my most recent short story on Radio 4. The story was a nasty jab at the consultants and junior doctors in the previous ward I had been in, in that very hospital. Of course, it was all transmuted into fiction, but I’d been so sad about the old doctor lying there politely dying next to me, that I made up a story where, although he died, he won honour from the teeth of humiliation.

Two things: the consultant whom I had had in my sights in that story on that day cancelled the appointment that had been made to investigate my fit further, and, thing two, although the radio was on in the ward, and there was my name, and my story, nobody but the author listened, very quietly. Fiction makes a low noise, well below a hum, in the life of a hospital. Books and writing are of interest only to those to whom they are of interest. This is a depressing truth, in itself of interest to fewer and fewer.

I had to go somewhere when the hospital released me, and it had to be where I could live without stairs for a minimum of six weeks. Annabel and Quentin invited me to Hampshire, for as long as it took me to start to walk again. They had dried me out and now they were again taking me in.

In Hampshire, I humped upstairs with my metal frame from the car to the room I was hardly to leave for six weeks, watched as I lurched and wobbled with kind attention by my first husband, with the practised eye of a horseman-yachtsman. He’s used to big animals and metal spars. He was also the encouraging kind of father who allowed the children to tackle stairs but kept a gate there too, a sensible facilitator. I toddlered my way up the familiar wide stair on my bum, hauling the Zimmer after.

I went to what has become my bedroom, that has seen us through many Christmas-stocking openings and two comings of age, washed with real soap for the first time since hospital, and entered a bed I got out of hardly at all for over a month.

Three busy adults, my older children’s father and his wife, and my older son, made time to visit me in the slits of their crammed days and evenings. They brought me stories of the world beyond and set up a routine that gave me a triumph of time and enlightenment, you might call it, an understanding of how they spend their days.

Land defines its rhythms: one lot for farming, its own; quite another for people. They moot the lot, divide the tasks, split them, and do it as it comes, which is naturally. The life of books, or whatever life I thought I led, seems by contrast inward and unevidenced. But it’s what I have to offer.

The separate personalities engaged upon the enterprise of the place made riper sense to me daily. I heard mowing, and hooves, and raking of gravel, gunshots, roomfuls of men, roomfuls of women, roomsful of both. I asked Annabel what she was wearing so that I could imagine her. I could hear when Quentin had been hunting because he would be in stockinged feet, having taken his boots off in the hall. I smelt bath oil in the early morning, then tea and cleaning products, then nothing till dinner unless there was a shoot. I could tell the doors of the visitors’ cars apart.

It was a happy time in the knitting together of family routine and of bone. I made laps of the landing on my Zimmer. They did not let me get away with moping. I was never alone in the house. The kindness was such that I was shy. It doesn’t do as a way to be among your own. I haven’t ever managed not to be.

During these, I think, six weeks, my older son inspired me to stop taking all those drugs. The bag of drugs I had with me was greater in volume than my bag of clothes, and it was after all autumn, time of big woollens and greatcoats. Over the six weeks, I cut down incrementally, until all I was taking were mild sleeping pills of an accreditedly non-addictive type. I’d asked for these after getting so hooked on Zopiclone that I panicked if I didn’t know I had substantial stashes and was upping the dose yet achieving less, thicker, harder, sleep.

Oliver’s reasoning was twofold. None of the family could see that things were getting better under the regime of all those drugs. If anything, they were getting worse, though no one was so ungentle as to say it but me.

And if, as the doctors warned I might well do if I stopped taking all the drugs, I had another fit, I would be in a place where I might be caught if I fell.

Just before Christmas 2008, I was almost drug-free. I was so blind that I had to rely on others to write my letters, and hot flesh was growing like silt around an anchor over my metal-bolted leg, but I was starting to have some clarity of thought.

That thinking wasn’t perfect, being tainted by solitude and fear, but it was less wholly reactive and fogged. I would wake in the night imagining that I had at last found the formula for being a wife who wasn’t and then go back to what shames and pains me, I think because it reminds me of being a child, the staring into the dark with hot eyes and a wet face, with the sense that there is nowhere to go where you are not a nuisance. I carry it like typhoid.

The most useful formula that offered itself was from a book I have not properly, that is not unblindly, read. It is by Emily Wilson. Mocked with Death: Tragic Overliving from Sophocles to Milton. I’ve dipped into, and liked, it, throughout the last blind year, though I’m aware that such dipping is unsatisfactory. Minoo has been my deeper pilot fish with the book. I started to believe that I had presumptuously over-lived, and that it was in reading Shakespeare and Greek tragedy that I would find an answer, were there one. Not a surprise, but a map.

The sad jingle that Dora Carrington used as her farewell stuck in my head. She took it from Sir Henry Wotton, though it now turns out to have been written by George Herbert. She couldn’t continue after the death by cancer of her beloved companion Lytton Strachey and wrote down the words:

He first deceas’d; she for a little tried

To live without him, liked it not; and died.

I knew I wouldn’t do it but the words were there offering their clean comforting specific inside my clearing head as the drugs receded. I’m told, as people say before they adduce crackpot theories, that it will take two years to get all those drugs out of my system.

Is it not curious that the doctor who prescribed these drugs never got in touch with me again, when I had been told that any reduction in, let alone cessation of, dosage, could be perilous? What can he have thought was going on? I suppose it never came up in the life of one so busy. We wreck once more against the rock of comparative values placed on time.

The couplet remains inside my head but I think it is there more on account of its balance and structure than its message. Rhythm injects it deep into the head.

I couldn’t work out what my point was. I saw myself as a tied-down giant, and Fram and Claudia as normal-sized beings who had worked out how to live, dancing free, in their triumph of enlightenment.

Why did I mind so much about the world, since I entered it almost never? Certainly, when people see a middle-aged woman whom they don’t know, they try to place her within the customary grids, and marriage is one of these.

I must make myself whole by work. After all, I am old enough. I am at an age when I might not long at all ago have expected to be dead, or at least widowed.

Those things of which I am unpleasantly jealous reflect ill upon me and are to do with her having been born into a context, rather than into my little family where the hotter personality evanesced and the cooler one thought personal conversation all but contemptible. Or so I surmise. I just don’t know. As must by now be clear, I’ve collected myself from here and there which may be the best I can do. In the middle are words and a capacity for recognition.