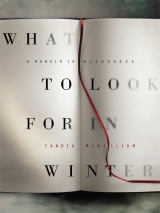

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

That is the frame, held, to which I shall return when I have found a way of not crying over spilt milk.

Now, for the company, I am listening to a concert from the Wigmore Hall in London and the main noise is interference, but it’s not unfriendly. It sounds like not the sea of faith but the sea of electricity; something that is a context, and one from which something clear may emerge. In the one case, a poem, in the other, music or light.

Katie and I this morning bunched up the wet branches of flowers that she had gathered, rhododendrons and azaleas for the funeral that was today at two in the afternoon.

It’s been a brute of a day for weather and the boat was not going to come alongside at the pier, but it did, for it was full of mourners, maybe twenty-five of them. Miss Angell, the aeroplane pilot from Oban, who works this route on a Thursday, flew in four more mourners in the teeth of the wind. The dead man leaves three daughters. A small granddaughter spoke in the church. Katie said that everyone was breathing with her to get her through. There was also a baby.

The lady lay preacher spoke.

There was a tribute from the dead man’s son-in-law, a big man on the island. The helpful breathing started again at the end of his words, when he described saying goodnight, every night (save the winters, when the dead man had annually gone down to Guildford to sleeve up and sell Christmas fir trees outside B & Q), so, saying goodnight, every night, with the same words, and that had gone on until this last Saturday, when there had not been the same exchange of goodnights, nor would be again.

The graveside, in the wind’s teeth, was well attended. Poems were read; Auden, Katie thought, and Keats and Wordsworth.

‘No,’ said her husband. ‘It was Auden. Keats, I think. Wordsworth, certainly.’

Katie made her face that signifies ‘Am I married to a man or an old deaf dog?’ and turned to her stove to poke at the lentils. She then asked a question that she didn’t need answered, ‘Why do people always say, when they know it can’t literally be true, that at least the widowed one will be back with the other now, at least they’ll be together?’

That terse code for attachment to her spouse, and the old van she drove earlier to the church before the service, its windows blind with gathered creaking sappy boughs of flowers, cream and purple, cream and white, pink and cream, creamy pink and splashingly scented, cut from the dripping flowering lichen-armed rhododendrons that crown this garden, boughs shining after all that soaking rain, short-lived wet falling caps of coloured flowers more than six men could carry, those are her way to catch life’s fitfulness.

Chapter 4: The Shaman in the Basement

In the afternoons since my eyes shut, I have slept densely for two hours if the day permits. When I begin the sleep, I cannot endure that I shall wake up and know I am alone. When I wake up, I know that I am alone and that I have to be on with it. Thus sleep accommodates.

There are several tricks writers use to get themselves moving along in a book when they are stuck: some use a walk; some a swim; some do chores; others either go to bed for the night on it or steal a short daytime sleep. I don’t have these sleeps nowadays because I’m stuck in my writing, but because I get stuck, at that point in the day, around two o’clock, in my life.

An ebb so low is reached that I feel my thoughts dwindled to just the one thought trawling empty along the stony repetitious levels and approaching the underwater cave mouth I do not want to look into, covetable extinctness. Not extinction, extinctness. It is a wanting to be dead, not, emphatically, a wanting to die. Moreover I can see it off with various forms of everyday magic, from folding sheets to washing my hands with welcome soap. It’s just not practical, though, routinely to address low-grade thoughts of suicide early every afternoon if you can avoid it. It leaves a banal plaque on the mind and is no doubt antisocial, like bad breath. That is what it is, bad breath. The breath so bad, it stops at nothing.

Not that I believe that we do not, or should not, live with the present consciousness of death. Or try to, since of course we cannot. It’s one of the blessings my mother passed to me, that appetite for life in the face of death. And she did nothing but make the gift greater by her own sudden departure. I have often worried for friends who haven’t yet known death so close that it will break them. My mother in her dying gave me every single thing she had and turned a morbid child to life for life. I won’t take my own life unless its prolongation is causing distress to my children. By when I will be incapable…Ah no, there are ways and means. We must talk, my darlings, when the exact, the precise, moment presents itself.

As a child, I used to wish that you could, as you can with many things, do ‘nasties before nicies’ and get death over with, buy it off by volunteering to do it first. But it’s like washing up before you serve the food. The abundance will have its toll and leave its trace, and must be made as though it had not been. I cannot remember a time when I was unaware that those I loved could die at any moment.

I don’t think that innocence is the unawareness of death. I think it is, at its truest meaning, want of self-interest, an incapacity to receive pleasure from hurting another, and, at its least true extension, a sort of blindness willed by others. Although it was I who left him (something I think of and repent of maybe sixty times a waking day) I hanker for the innocence that was the world Fram and I had. Maybe it is just that it is available to regret the time before a catastrophe as prelapsarian. But that long mutuality feels like a close-sown flower meadow to me, a meadow that I harrowed up. Anyone raised with hymn-singing will hear the tone, the heart’s field red and torn, the foolish ways, the still small voice, the pity that dwells with the Peace of God.

My afternoon sleep is longer than is usual for a siesta and I feel a bit guilty about it, but if I don’t go to bed by three at the latest there will be the equivalent of tears before bedtime.

If I push on through the afternoon I unravel at the least thing. I don’t show it, but I direct at myself a regular stent of internal poison when I am tired and blindish, that can result in inelegant over-reaction to other people, extravagant concessiveness and really implausible self-sidelining or peculiar self-directed violence that is I suppose directed at the world.

It is like having been eaten by a gigantic menaced two-year-old and not being able to escape from her body. Since I am most often alone, these reactions may be to the radio or to an idea. If I don’t have those two hours of sleep, I start to disintegrate, to lose and cease to recognise myself.

It’s not, I don’t think, an Alzheimer’s-like cessation of recognition. I recognise my monster self, the self in whom the black humours run high, and I wish to bring it out into the light and scotch it like a snake. I tempt it out with a big bowl of rancour, watch it approach to drink, and wait to set about it with that knife of self-contempt. Failing the knife there is the cudgel of bleakness.

The bleakness involves taking a close look at what my actual situation is and turning away every time I offer myself some hope. It does not improve things that by this time in my unsighted day I shall have put blinkers on inside my head as well as the compromised sight beyond it, unless I keep things calmer with those two hours in the afternoon.

My dreams are still sighted in the way I used to be.

Perhaps now is the time to address any bright side of my not-seeing. I am used to looking for bright sides. Usually, though, being bright, they will have shown up if they are going to.

Long ago, when I was well inside my marriage’s shelter and could see, with no thought of either safety or sight being in question, I was much interested by the writing of Ved Mehta. His blindness, his Indianness, his dwelling in the reading world, his insistent intellectuality and his pursuit of love, his utter failure to accept that one mustn’t grumble, his want of need to camouflage within consensus, all appealed to me. Try as I might, I cannot find his work in recorded form. All these traits but blindness are shared by Fram, I see.

Why was I interested in blindness, so interested that throughout my reading life I sought out books about it? I think that it was simply an impossibly difficult state to imagine, and probably among the worst routine bad things that can happen. I think that I returned repeatedly to the matter of blindness because I believed, and do believe, that we are all to some extent metaphorically blind and this is something at which I have squinted, more or less blind-sidedly, in my work.

Or rather, I think that the gift is rarely given us to see ourselves as others see us, that we do not see others as they see themselves, or if we do they might have preferred that we had not, and I am sure that the whole event is but half glimpsed, if that.

I do not believe that when I was reading books about blindness, metaphorical or not, or by blind writers, by Stephen Kuusisto or José Saramago or Henry Green, let alone by Homer or Milton or Borges, I was stocking up in advance on works that would come to my rescue in my later darkness.

If a person who goes to prison happens to have by heart a good deal of verse, that is an arbitrary blessing, although a great one. We cannot prepare for these blows. All we can do is our best.

The shaman of Portobello had her pitch in the sort of set-up that is familiar if you have visited the fringes of alternative cure. Outside, it was an unexceptional shopfront in a small red Dumfries sandstone terrace of businesses, a tiler, a greengrocer, a Londis. To the left of the terrace a narrow close led down to the North Sea and its sandy shore, grey cockle and sea-glass sand crunching over and again under low waves that day.

I was early and had left my son to listen to his chosen writers at the Book Festival. He knew about the shaman and would have been happy to come along. In the event, I was glad he hadn’t so that the idea might remain in his mind’s tropical zone. At first, the impression was of an entranced and definitely decommissioned beauty parlour, with just a hint of those therapy rooms that induce a special claustrophobia relating to fruit tea and uncleanliness, lost hopes and women beyond romance having that new, fairly frugal, fling – with themselves.

I held open my eyes and peered through plate glass into the little carpeted shop beyond. The keynote shades were from the calming gamut. I am unsuited to alternative medicine. I do not like yellow on walls (or on book covers; the how-to-commit-suicide-and-not-be-found-out book is actually yellow, in a bossy life-affirming way). I am afraid that I will break wicker furniture. That said, I’m always curious about what is on people’s mugs. And if there is a mug tree, I learn something. Mugs don’t grow on trees.

On the wall behind the door, there were leaflets about hypnotherapy that had gone stiff on the noticeboard where rain had forced entry. There was an old and duly respected kettle, with a tray to catch its spillage, and a cloth for the handle. There were head massages on offer in the window from a young woman with a surname from deep in the Scots nobility; a novel in that, as in all disjointedness? She was also offering journeys into past lives at reasonable rates. There were long-overdry dried flowers.

Because I have lost the notes I made that day, I am collecting detail up from my memory-beach where things are ground down and worn away by the days coming in over one another like waves.

How can I see detail and have as my illness that I cannot see? It is one of the peculiar things about blepharospasm that sometimes the twitch and tremor leave you in peace and you can see. But if you badly need them to do so, they take a tighter grip and blind you. I remain observant although, as I am now, I need guiding around this house that I have known for over forty years. It’s hard to explain to those you know, and impossible to explain to strangers without boring them.

Claudia the shaman appeared. I knew it must be Claudia because she practically made the car’s bumper curve upwards, she was so smiley and dainty. She parked her Mini and hopped out, a small Latin woman of perhaps twenty and pretty as a picture, long black hair, gold skin, smile to make a morning, lots of jerseys and a poncho. She had a soft raffia basket, which she put over her elbow.

She asked, ‘Are you Candia? I am Claudia’, which always strikes me as an almost palindromic and certainly confusing thing to have to say, and unlocked her premises just like any shopkeeper. There was no alarm system. That was a good sign. Spirits worth their salt can protect their premises.

She had the glow and pace that make normal gestures feel like bestowed privileges. We settled with our mugs of fruit tea. After many years I have not worked out which blend is the least nasty.

She was undoubtedly a hibiscus flower along this cold shore. She took off her sensible boots and some of her thicker woollens. It was, after all, August. Settled at her desk, she took a look at me over it. She was tiny, and perhaps not even twenty. I was sure that I was growing.

Soon I would fill the shop.

She started to ask the questions and I began to bore myself, retelling my much-handled story. Often, when I am telling medical people or other putative therapists about it, I start to think, ‘Oh it’s not that bad really. Why don’t I stop troubling you this minute?’

Shaman-Claudia sat on her chair like a sprite, not in it like a weighted person. I noticed a tall thing in the corner that looked as if it might be a rainmaker, one of those hollow stalks full of seeds that fall with a sound like sudden rain on big leaves. I was sure there were maracas somewhere about.

There is no point doing these things with half a heart.

We went down to the basement; it was clean and fresh. It might have been in a modest East Coast B & B, before the Scottish Tourist Board fell to the torrid charms of air freshener and full-strength potpourri.

I lay down as I was told, Shaman-Claudia dimmed the lights and lit a candle, passed a number of large feathers, could they have been from a condor? over me, rattled her various instruments, and settled, with a gravity that made her small form intensify, to calling down the relevant spirits.

At no point did I even feel like laughing. I am not unusual I’m sure in testing myself in these circumstances. As a rule I can get through with manners and going deep within not to retrieve past selves but to avoid being hurtful. At no point at all did I not take literally all Shaman-Claudia said. That was her achievement. The bogus couldn’t get a grip on her anywhere, possibly on account of her wholesome physical person. We entered the spirit world.

That, in a basement in Portobello on the East Coast of Scotland, takes some strength of being, when a complete stranger is rattling and chanting over an old Scots body, calling up its animal familiars. Mine arrived at once, punctual as their keeper, or whatever one is to one’s animal familiar. One was a small tiger not through the kitten stage and with very large feet and the other was a whippy and talkative snake.

There is no surprise for the reader there at all. They come straight from my library of predictable attachments and concerns, my usual wardrobe of metaphors. Maybe the tiger was related to Ormiston, maybe the snake to our first mother, Eve.

The tiger told me to walk towards Fram and Claudia and to say to them what was in my heart. My normally rather distanced way of speech, at least with strangers, became direct.

I spoke the plain words of affection.

The headache that I carry which combines the strain of my condition with the puzzle of my situation became acute.

When any physical sensation occurred, Shaman-Claudia identified it well before I had expressed it to myself. She told the headache to be off. It did as it was told.

I explained to Fram and Claudia all that I wanted for them and their happiness. It came out without the administering of blows to myself.

The snake was a subtle customer, as tradition dictates. In a gesture of elegant animistic diplomacy from beyond both rationality and the grave, it turned out that the snake was my late mother-in-law who had in life feared snakes terribly. It was a nice snake and full of excellent advice, all of which I was anxious to remember in that way you are in dreams, because you know that this is it, the last, the only chance, before…

You wake up.

There is, when you come round after these things have gone well, or reached something important, a sense, I know now after several brushes with these other angles to healing, that you are on the edge of flu. You have come down with something.

We had been over an hour in the basement with the small tiger and the snake. I checked all the graphic works on the walls to see if I had glimpsed a picture of either creature before going under. Irreproachably nebulous images or nice Scots scenes hung on the walls. My eyes were fairly open, and did not insist on closing.

I was rather competitive about my familiars and asked, ‘I s’pose everyone has tigers and snakes?’

Shaman-Claudia was wise to all levels of the question and avoided it. Like all convincing practitioners of creeds, she had no exotic manner to her although her flowerlike head and tininess made her exotic. She was tired after her exertion, like a dancer or a hod carrier.

We had more tea, and chatted about the usual ice-breakers. You get used to this upside-down intimacy, drawing people out about themselves after they have seen you weeping in the foetal position. I am unable to say how this rhythm lies in relation to paid sex though the thought of the parallel has crossed my mind.

I have sometimes wondered how many women like me pay to be touched, completely innocently, by strangers, just for the specific it may offer against loneliness? I have even resorted to manicurists during a bad three weeks this January, but I couldn’t keep it up. They spotted me for a first-timer at the salon in the Gloucester Road and I was shy to go back after I realised that I was too guilty and not rude enough and don’t like coloured fingernails. But I did love the tender Polish touch of the girls with their cream and patting and the little bath of wax for your fingers’ tips.

Shaman-Claudia told me a bit about herself now. She was, despite appearances, rather more than twenty. She had two children with her Brazilian ex-husband, one nearly grown up, and she had recently remarried, a Scotsman, an ex-minister of the Kirk. Her personal tone was calm, amused, taken at a magnificently easy pace. It is unusual for the very small to be magnificent. Her own magnificence lay in this: that, like a creature, she was at once serious and weightless. She was one of those rare people from whom you get the strong sense of what the world is to them and how it would be to be loved by them. She was both unstrained and entertaining. It was hard to be defended or harsh near her. She had shown me at the very least that it would be by ceasing to struggle and writhe and try to exorcise my grief about it all that I would take the hook out of my heart and stop re-impaling myself on it as I had been doing for months to no one’s benefit.

She was one of the beings graceful beyond words amid this year’s, literally, unsettling thaw. In a thaw, things rooted are induced to shift.

I began that day to try to go limp against unhappiness, though I have to this day far from succeeded.

She zipped up her boots and put on some of the August jumpers, greeted her friend Amy the film director whose illness Amy firmly knows Shaman-Claudia dispelled, and gave me a hug. She had the matter-of-factness of the seer, which is like being teased by a clever child. I liked her a lot.

It is very competitively priced, as far as I can see, the shaman world of East Scotland, and worth every silver bawbee.

Amy and I went paddling in the shiny grey sea not even a block from the shaman’s shop. We got sandy toes and walked to Amy’s car in bare feet along the pavement. I cannot remember if we did buy the ice lollies that false memory supplies, as I would have in Portobello with Mummy after swimming.

When I got back to Minoo, he had been listening to Will Self. He was particularly charmed by Will’s family-man graces in the authors’ yurt, and how he put on his cadaverous churlishness so as not to disappoint his fans, who were queuing two and a half times around the square where the Book Festival is held. Minoo was delighted because he was pretty sure that Will had his mother-in-law with him. Not surprisingly, Minoo is a devoted proponent of the extended family. I hope this doesn’t embarrass Will, who maximises the stretch of his alarming outer gifts while cultivating his inner delicacies of grasp and attachment. A very tall man, he has been unafraid, in the metaphorical sense, to grow right up.

I told Minoo over his teacake and butter about the companion-animals. I didn’t say what kind.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘a tiger and a snake. That was me and Granny, looking after you.’

It is very seldom that his grammar falters.

‘Granny and I,’ he said, before I’d breathed.