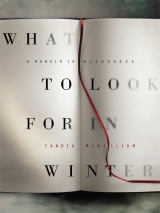

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

LENS I: Chapter 6

Elegance of posture was a great thing for my Henderson grandmother, my mother’s mother, the opera singer. She held up her noble head right till the end in her nineties. Her silver hair streamed down her back. She could sit on her hair, as could my mother and I once, and my daughter. Each of us has had it chopped at some point. My grandmother shingled hers in the twenties to irk her ferocious pa. My mother did it to manage her hair and I suppose her life just before she died; women change their style at important moments in their lives, we are told.

My stepmother did the only sensible thing after Mummy died and had mine cut off. It was a weighty reminder of my mother, a great pest to maintain, a personality in its own right and attached to one already disobliging; it also encouraged nits. For years after I had my long heavy striped brown plait (the Scots word is pleat) in a box; then I lost it after I went away to school in England. My daughter has lovelier hair than mine; it is fine and silver and grey-gold, and thick as fairytale hair. It weighed down her small head dreadfully I now sometimes guiltily think. She made a practical teenaged choice to have a lot of it cut off. It was the right thing to do. People had asked her about it before asking her about herself, as though she were a unicorn or a mermaid and it, the massive silky rope, her horn or her tail; it was a natural feature too much emphasised. Her hair is so thick that it has to be thinned in summer. It is miraculous stuff, glistening and falling with a kind of lunge of health. Mine I cannot bear to cut. I’m getting like my grandmother Clara Nella Henderson, the tines of whose silver plait fell to nearly her waist on the last day of her life, when she told me a great white bird was at her window and I thought in relief, ‘Oh, she has got some faith at last in her bitter life and at the bitter end.’ It wasn’t an angel. It wasn’t the Holy Spirit. It was a herring gull driven inland to eat from the refuse bins of Reading General Hospital by that Christmas weather. She died in the night before Boxing Day. I want to think that we were reconciled. She thought that last day that I was her daughter, my mother, Margaret, whom she hadn’t found easy either.

I am growing increasingly like my grandmother. When she was getting infirm and failing to eat (I believe that she starved herself to death), I looked at ‘places’ for her to go. She fought against it. I took her to one. Most I had visited had been too upsetting to contemplate for her, but this one seemed ‘nice’, whatever such hell can be. There was a real room, and a real view; the nurses were, seemed to be, kind countrywomen. I smelled no fear nor piss nor shit.

My grandmother, whom I called Nana, was at over ninety still as tall as I and had been taller. She was very thin. Her lovely legs were sticking out of a garment taken from a hospital pool of such shapeless clothes. At home in her bungalow on the estate in Reading hung and lay her immaculately cared for frocks and cardigans, her evening gowns, her treed shoes, her gloves. She was, as the dying often are, terrified of disgracing herself, of having an ‘accident’. She did what any sensible child would have done in these circumstances. Terrified, about to be alone, as she felt it, maybe about to be abandoned by her own flesh and blood, she made herself, although she had little in her stomach, violently sick. The nurses were not kind, not understanding. We left, my imperious beautiful grandmother holding a grey cardboard kidney bowl aswim with bile and mucus. My grandmother carried the day, all her own teeth in her head, her gracious smile of triumph and relief as we left transforming her proud stony sad face for close to the last time.

I am growing more like her now, afraid of the powerlessness my body is forcing me towards, scared stiff of being disposed of, tidied away, thinking I maybe should do it for myself. I’m just over half the age she was when she gave in, and even then she forced herself to do so by refusing food and water. She was a far stronger character than I and I do not actually want to die. I find notes that I have written to myself and they remind me of my grandmother’s diaries that I dare not read. They’re engagement diaries, only, but it is enough.

She had been alone from the night when her husband, my grandfather, tried to murder us both in the drawing room of the house he himself had built, The Folly, West Drive, Sonning-on-Thames, Berkshire. He was a strong old man, older than his beauty wife. He was doing the right thing by trying to kill us, because he had long ceased to ‘know’ us. He was protecting his property, as he saw it, from strangers.

It was my first half-term out from my English boarding school. I had a major scholarship, but it was effectively my grandfather’s money that was paying the rest of the fees. The wheel of separation of child from antecedents by self-made money had begun. I could see that my grandparents were more conventional and right-wing than my father and mother had been. My Henderson grandparents didn’t like my father; my father’s family looked down on the Hendersons. Their separate, profound, kinds of musicality were incompatible. Professional musicians on both sides, on one the Church, the other the stage. I was the oil and water shake-up. My mother had been dead for four years when Grandpapa tried to kill his wife and his granddaughter, thinking us intruders, in his folly.

Grandpapa went for Nana with the hardwood truncheon he had used in the Army in Jaffa in the war; she yelled to me in her deep grand stagey voice, that never slipped, even as he thumped her (she was Scots-Irish cockney with the loveliest and most gold-rolled speaking voice of my whole background, including those backgrounds that were yet to arrive), ‘Candia, call the police.’

I did, but I couldn’t tell them how to find us, and my grandmother, holding down her spouse, himself strong with fear and insanity, gave me calm, self-possessed instructions to relay down the telephone to the police.

She had spine. It must have been worse, I think now, because I’m sure that she loved him, and she had a long widowhood to endure alone after who knows how long of concealing his decreasing stability. She did it all with poise. Her happiness in her widowhood lay in producing opera and operetta. I cannot think that I contributed to any happiness at all. I was a nuisance and a let-down, plain, brainy, a lefty and a snob.

Her engagement diaries are lists of small sums and presents she has given. She was generous and well-regulated. She was more hospitable than greedy and had no appetites but cigarettes and music and like-minded company, which I was not to become for her. She watched, it is clear from my inheritance from her, those little frightening diaries, my marriages and my giving birth and my small success as an author as perceptible through the press and ‘kind’ neighbours (she took the Daily Express), with increasing disgust. She would ask herself in her diary whom I had paid to get all this attention. Even reviews that I wrote she noted carefully in her diaries, not from familial pride but because she felt that they were bids for attention, that I had somehow paid to appear in the paper. She regarded my defection to the toff-class as a betrayal of decency. I didn’t know my place. Yet she was the grandest woman in her manner, as she smoked, or took out the wrapped sandwiches from her refrigerator before an after-rehearsal impromptu around her piano, or as she hailed the bus from Caversham into Reading, and stepped out to take coffee at a department store with a kind of film-star duchessly hyper-demeanour.

How odd England showed itself to me, a Scots child through and through, and how late I have been to grasp how I must have hurt my grandmother and let her down, by making what some few souls thought was a marriage advantageous in worldly terms. My mother failed her parents by marrying a man far more educated than she was, a man educated, toxically, as her parents saw it – socialistically – to place value on things other than money and respectability. And when I married a man who was many things superb beside his station, my educated father briefly – for he came to love my first husband with a deep affection – felt, momentarily only, a stab of something surely analogous to my grandparents’ sense of class betrayal when he had married Mummy. My father blamed me; he mistrusted my appearance, I think, and thought of it as a spangled meretricious lasso. I suspect my father pitied anyone who was going to marry me; I do not know this. I didn’t know I had the lasso to throw; we scarcely ever had a personal conversation, though all our exchanges were elliptically personal in their encryption; we shared matters of the eye.

Nana vowed upon my first marriage never to speak to me again. She was hurt. I married a toff and then a Pakistani. I did not have a respectable job. I was horribly visible. My grandmother never knew the odd congruence – starting from so different a place – of her own emotions and those of my Parsi in-laws, who so disliked all the publicity I received, reflecting, entirely reasonably, that one pair of ridiculous fashion tights, credited as costing some shocking sum, might water a village in India, and that no proper wife, no proper person, no proper writer, appears in evening clothes not her own in order to help publicise a book that is in literary terms respectable.

My grandmother thought that the education she had effectively paid for had separated me from her and made me pretentious; she was fed in this apprehension by friends who passed her all the disobliging cuttings they could. An equivalent drip-feeding went on to my poor parents-in-law. Neither of these things – the separation, the pretension – was precisely the case, but it helps worsen the hurt to coarsen the terms, naturally, and my grandmother and my mother-in-law were each attached to private suffering, a plot laid out for one by starting to earn her living aged five on the stage and caring for a blind sister, and for the other, perhaps, by the Partition of India and Pakistan in the year of her marriage, for she was from Bombay and her husband, her first cousin, from Karachi.

That my grandmother and I did speak again is due to telephone calls, made by each of my husbands, and each call concerning the arrival of a child, her three great-grandchildren, separated from her, as she understood it, on account of the bitter prejudices that rack this country still, by class in three cases and colour and creed in one, and yet – when at last she met them in her final year of life – she felt them entirely hers, her great-grandchildren, the older of whom have her posture and her gamut of social smiles and the youngest of whom has her appetite for libretti.

I have at last started to let go of the dear stone, that cherished discomfiting notion that my grandmother did not love me or my mother.

She loved us too possessively, too angrily, too silently, in the way of the day. It was her stone, a stone axe, beautiful and held behind her lovely face like obsidian, never letting her yield. I won’t feed my own stone by rereading her hard, withheld diaries, but must instead recall that at the end she let me hold her hand day after day, whichever one she thought I was, my mother or me, and that she left me in her will an envelope of mica windowpanes for a solid-fuel stove, each the size of half a playing card, little slips of crackly pearl for feeling heat through and for looking through, into the fire in our pasts.

My mother very occasionally brought home from her trips to the grocer Young and Saunders, or from Rankin’s the fruiterers at the West End, a pomegranate, in tissue paper. She would give me a pin and two plates. (Is this the sort of thing to which people refer when they say, ‘We made our own fun’?)

Mummy would cut the pomegranate into four, put on my apron, which was modelled on a French child’s smock and sewn by her, in her constant search for rational and appealing clothes for children, and let me take the chambered, compressed, treasure apart, with one plate for the leathery but blushful skin and the membrane that you could look through, and the other for the pressed red jewels, which I was allowed to eat with the pin. So long did this task take – a whole afternoon – and so magical a treat was the process that I was not surprised, when I read in my anthology of myths, The Tanglewood Tales, about Persephone – to learn that she had tumbled to a pomegranate’s charms in Hades, and that the seeds were measures of time spent with or without a mother.

LENS I: Chapter 7

Painstaking effortlessness, curiosa felicitas, was my father’s, apparently idling, actually supercharged, gear. There may have been something irresistible to him about my mother’s lavish appearance and her extremer way. But it was also, time showed, at some level repulsive. The quick term for this is, I suppose, a fatal attraction. They were stuck under the net of convention and another net of passion that had charred to distaste on his side I think. All this is speculation.

In marriage, and this is less speculative, since I have twice failed to understand, to implement and to reverse the disintegration of this, we are, or I was, trying to answer the loss and absence that the other has felt. One hopes the other’s gaps will be filled by something that one carries within. But somehow instead we may create what we most have feared because it is familiar. Perhaps everyone but me knows this.

I saw my mother be craven to my father. Cravenness has no place between any two people. Craven is the claw of the mode most repulsive to me of any, that of ingratiation. I hate full frontal flattery and its oils the more, the longer I live. My father lived perhaps a little too sternly by the exigencies of understatement; my mother’s overstatement I know, because I am like it too, was authentic, was intensity of feeling, terribly banked down. I’m like them both, dry and pyrotechnic; but you need to keep powder dry. I don’t like slobber. It is the slaver kills and not the bite.

Marilyn Monroe killed herself in the August of 1962. I was already much taken by suicide, but only as a means of transformation, the death of one way of being in order to catalyse the birth of another, as in the Beast becoming Jean Marais in the film by Cocteau of Beauty and the Beast, to which my parents were attached and which they took me to see whenever it was showing. Cocteau himself had designed the programme and poster for the first Edinburgh Festival. That was one of my parents’ worlds, the Edinburgh arts world. When the Traverse Theatre was born, Mummy cooked for the actors. The Incredible String Band lived in one of my friend Janey’s father’s barns. Our street had the poet George Bruce and even Chopin had stayed in the Crescent some time before, no doubt on his way to visit Miss Stirling at Keir, where there was said to be a piano he had played. There were recitals in the Chopin house, which belonged to a musical family. I remember my mother making zabaglione for the mime artist Lindsay Kemp. I felt at once a bond with him, to do with discipline, extremity, outsiderness. I was drawn very young indeed to the company of gay men. A matter of talk and of establishing hidden ways to utter; puns, jokes, playing around. This line in transmission ran deep. My father totted from a skip quite late in his life an old ironmongery sign made of cast-iron letters. He reordered them up the stone stairs of the house: IRONYMONGER.

I read all I could about Marilyn’s death. I remember reading Life magazine, lying on my stomach, of course, on the floor of another family, and getting the first intimation of why she really did it that made complete sense to me. Life had silky pages that smelt of my lino-cutting set.

The words that made sense were, ‘Breasts, belly, bottom, soon all must sag.’ The alliteration, the coarse mimetic bounce of the words and the downward fall of the sentence added to its crude potency; the misogyny agreed with some knot within me of self-dislike, and I saw that that was one reason to die (or transform yourself, as I saw suicide at that time, before it had come closer), that Marilyn had shifted shape by choosing to stay the same, by dying. I collected information about female suicides long before there was one at home, whose case I have refused to study until recently. I was interested as a quite small child by women who kill themselves and that they will often choose to wear make-up to do so. This may have changed by now. Many suicides are drunk or otherwise chemically changed, and grooming, as I have cause to know, is not a part of the throes of advanced addiction. Women used to get into their prettiest underwear, their nicest negligee, in order to be negligent of themselves in the highest degree. I don’t know what happens now that there is so great a passion for pictures of women falling short of the impossible standards they have set themselves in life. And if we think at all, we know, even without seeing photographs of really dead beauties, that the prettification will in time be all undone: the mouth falls open, the stomach rebels, the bowels let go, the worm or the fire do their work.

I was keen on the self-betterment side of suicide, so convinced of angelic afterlife was I, on account of knowing for sure that I had a guardian angel, partly because on my nursery wall was a reproduction of Ghirlandaio’s painting of Tobias, slung with the fish, gall from whose liver was to cure his father’s blindness, and his Angel, and partly on account of my guardian angel having told me firmly not to turn on my bedroom light switch which went on to give my mother a great shock later that day. My mother was undoubtedly attractive to shocks.

Also, someone had written on my nursery window with a diamond, which showed that a child or young woman (the writing made that clear) had lived in that small tall shuttered room before. The words were ‘October 1893’. What was important was that all the letters had serifs, so once someone with a lot of time had looked out over the garden and over the wall to the river and up and over the narrow walkway to the railway bank, maybe, and certainly within knowledge of the cemetery over that bank, where The Red Lady, it was known, walked by night and had done since thirty years before my guardian angel had written her tidy date on my windowpane.

The idea that suicide is a way of refining oneself is not new, to humans, to children, to girl-children, to girl-children of religious bent, nor to anyone who seeks a solution. Often the solution sought is temporary, and this temporariness cannot be ensured. Anorexia is its slower mode, taking appalling hostages. The joke of it in my life was that the long suicide I took on was the perfect undoing offered by alcohol, and I really didn’t know that I was doing it until very nearly too late, by when I had indeed transformed myself by taking the clear liquid solution.

Marilyn died and as a child I loved the most the pictures of her with her intelligent husband, always so evidently and photogenically intelligent, Arthur Miller. His dark looks established, together with almost all medical doctors whom we knew and the cold Edinburgh weather, which necessitated that men wear long tailored overcoats, what could be called my ‘type’, as in Proust’s ‘she was never my type’. Later this received a top dressing of Sydney Carton from A Tale of Two Cities and of the hopeless clever drunk Charles Stringham from A Dance to the Music of Time, Prince Andrei too. About the only thing I can say in my defence in this area of daydream is that I have never fancied Vronsky.

Hopeless, clever, drunk; that trio of adjectives reminds me of something that happened on the same day as I read that sexy and offensive sentence about Marilyn, and it reveals what conversation was like in the long afternoon winter drawing rooms of Edinburgh among my parents and their friends. We were some doors down from the house where Compton Mackenzie would hold court in his great downstairs bed. ‘We’ were, I suppose, another family, of two parents and four children, a grandfather and a very thin aunt who I realise now was dying, and my parents. The oldest daughter of the house, about sixteen, was reading The Flight from the Enchanter or some other novel by Iris Murdoch that I had seen my mother read.

‘Why do the adjectives in Iris Murdoch’s books come so often in threes?’ she asked.

So the game was to use only triplet adjectives for the afternoon and all of us played it. The taste of that house was black treacle with yellow cream, in bowls of uncooked oats. Over the dining table there was an oil painting of the mother, Marjory, in a hat covered with flowers. The father was a landscape architect. All the children save the boy, Simon, had dark eyes. Simon told me not to let people know how much I knew if I wanted more friends. We were six and took turns on the rowing machine that was there for the frail ones in the family. Simon and Polly were twins and I was a severe bore for them because I tried to copy them in order to be normal; copying twins who are not identical is a tangle.

But who to be?

When my mother died I had someone to be, perhaps. But it was in the days before people spoke about such events after they had happened, and we were in Scotland, where speaking was less the done thing, even, than in England, or speaking of dramatic personal matters, or personal matters at all.

I suppose there was some mongering of scandal.

But Scotland it was that saved me. I am sure of that, for all that I was sent away quite soon. The being sent away very possibly fixed Scotland for me, deep-laid as it was in a way that I had not understood was happening, as my father drove me and my mother all over the roads, never as the crow flew, but round and deep about and through the sea lochs and mountains and glens of the North to look at the houses, castles, villages, mills and towns he worked to preserve.

In the back as he drove, I sang my sagas and sucked on a fresh lemon against carsickness. The lemon had come, my mother had always said, as she pulled it from her travelling-basket the moment I started to whine, from sunny Italy. Sometimes it had the leaf to show for it.