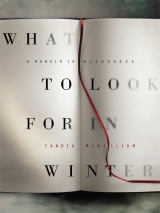

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

LENS II: Chapter 7

Wotton became my place in the world, by which I mean my place quite far away from the world. Perhaps it was here, in its tall rooms and in its perfect self-contained hiddenness, that I relapsed into my inborn habit of reclusion. Wotton never did feel lonely, because I discovered that Mrs Brunner shared my affection for in-house mail, so that we left one another letters almost daily if we had not met in the rose garden or taking a walk under the chestnuts by the first lake. The park had been laid out by Capability Brown and there was, to the small landscape in which the house lies, an adaptation to mortal scale and vision that made walking along those lakes past their half-resurrected bridges and temples a humanising experience. Before the first lake there were two Doric-pillared Grecian temples. Oliver and Clementine and I would take bread to the swans who lived here. On the farther lake lived Canada geese with their two faithful watchmen-geese standing apart from the flock. Returning from walks to the house with the children was each time almost impossible to believe. We would pass a herbaceous border, leave the rose garden to our left, go and sit in the long grass on a bench by the wishing well and be paid visits by Solomon and Sheba, Mrs Brunner’s peacocks, who, she said, had probably flown over from Waddesdon, which looked down at Wotton from the east. If it was a sunny day, Mrs Brunner would call us up on to the back steps of the house that led in to her own quite breathtakingly sparkly apartments. She always had a treat for the children, though her appearance was in itself the greatest treat, for she was brightly manicured and preferred to wear the colours of the rainbow. She smelt good too. Inside the house the tall windows had shutters that were barred at night across the dizzy original glass. Each shutter had its hole, an oval about eight inches tall, through which to look out for the moon in its transit.

There were secret rooms and rooms filled only with ebony knickknacks. One room contained only objects made of mother-of-pearl. Clementine’s and my favourite had a high curved ceiling edged with shining pearls, each the size of a tennis ball, in freehand plasterwork; below this lay disposed Mrs Brunner’s own extraordinary wedding dress and that of her daughter, so that the whole room had a silvery-fragile bridal air, as though from the story of Beauty and the Beast. It was like the dream of a princely wedding that the poor Beast might have prepared.

If Mrs Brunner was attached to fairytale stage sets, she was also a brilliant chiseller at all possible architectural or state-related organisations that might help her to protect, conserve and reveal her exigent treasure trove. Even when I lived at Wotton House, she discovered an eighteenth-century ha-ha behind the nineteenth-century one, an indoor fish pond laid with tiles and braced with elegant bronze pillars, and several further follies in the woods beyond the second lake. I do not know how old Mrs Brunner was, though I imagine it would be easy enough to find out. Her role in our lives was so supernatural that I prefer my ignorance. I never called her by her first name.

The house within has a trembling stone staircase with wrought-iron work by Tijou that quivers as one mounts the stairs. The vistas within the front hall suggest the receding background of a Renaissance painting, exemplifying and playing with perspective. The hall is full of light, very high, and paved with black-and-white marble in squares on the grand scale. In winter, an open fire was set in the fireplace in that front hall, where the children and I left carrots and biscuits and, at Mrs Brunner’s insistence, a tot of brandy for Father Christmas.

It was at that first Christmas after the sadness of our parting that I saw how a pure flirt like Mrs Brunner made things easier between me and Quentin. The great lack in our lives, probably thanks to the premature death of his parents and my mother, was grown-ups to teach us how to pull the splinters out instead of driving them further in.

We developed a pattern, familiar to many families, whereby the children spent half the holidays with me and half with their father, and alternated, insofar as it was possible, at weekends. Thank God there were the two of them to sustain one another and grumble about this together, since it was to go on for a long time. I remember standing on the nursery floor at Wotton having tidied all their toys away and looking at the departing car, thinking, ‘What is in their heads?’ At around this time I wrote a children’s book and illustrated it. It was really about Oliver and Clementine, of course, and it was always going to be destined for Quentin, who has the paintings now, which are portraits of his children.

There was no sense of unsafety at Wotton although we were an old lady and a younger woman and two small children alone. The whole place was barred up so snugly that its only burglar, during my time, was a ferocious wind that punched holes in three fragile windows, whose panes simply couldn’t take the brunt in spite of their delicate ductility, like that of sails.

I had the notion that I would write some short stories to make a bit of money. I sent five to Auberon Waugh at the Literary Review. He sent them back with a kind note saying that he and his wife had enjoyed reading them in bed. I imagine this was a tease. I then tried applying to The Archers to see if they would like a new scriptwriter, but they wouldn’t.

There’s nothing for it, I thought, but writing a novel. I had bought my father an electric typewriter that he had seen the Observer newspaper was offering at a reasonable price. He passed me his old typewriter, whose keys you really had to think about pinging down like those of an old till.

I wrote my first novel, A Case of Knives, in my bedroom at Wotton House, a room whose mirrored cupboards chopped up the images thrown by the circular mirror the size of the shield of Achilles on the opposite wall.

In the South Pavilion lived Sir John Gielgud. In the morning, you could see his partner Martin taking their shih-tzu for a walk. Opposite Sir John lived an elegant German lawyer who worked between Washington and London and kept this celestial pavilion as his country hideout. He often entertained my children and me to Sunday lunch. His line in girlfriends was terrifying to one who has never seriously in her life thought of wearing leather. On the whole they turned out to be very nice and, moreover, to do things like run Lufthansa’s legal department or own a chain of supermarkets in the old Austro-Hungarian countries.

Behind this exquisite pavilion was a courtyard containing a long house that had at one point been where beer had been brewed for all the servants employed in the main house. In this house lived Graham C. Greene and his family, including at one point his mother Helga, with whom Raymond Chandler had been in love. Quite briefly, Clarissa Dickson-Wright was his housekeeper, and once she babysat for me. At this point she and I were both what is called ‘practising alcoholics’. I had no idea.

Every day when I woke up at Wotton, I was glad to do so. I suppose that means that one has found a place in the world. Once I saw fox cubs playing leapfrog on the back lawn. I so loved being there and when the children were with me it felt as though beauty in itself might feed them the things that disunity was taking from them. It was a hopelessly over-aestheticised view, I can see. But to this day, I like it when I know that they are in the places where there is beauty.

Mrs Brunner met and charmed my father; they were exactly each other’s sort of thing. Daddy, possessed by architecture, crazy about Soane and handsome; and Mrs Brunner, obsessed by her great charge, her house, and very fond of flirting. Mrs Brunner welcomed other friends as well, though she was a great one for taking what the Scots call scunners. She was absolutely beastly to the boyfriend of one of my best friends whom she regarded, quite correctly, as treating my friend unkindly. If not a witch, she was an advanced telepath. She could also dismiss people simply on the unfair grounds of their want of physical attractiveness, and she was extremely fussy about fairness between the children so that if someone bought a present for just one of them, there would be a note requesting the presence of the giftless child in Mrs Brunner’s drawing room where would be laid out a fairy feast and some compensatory present.

It is quite a feat for a mother of an only child to think in this way. She had at some level remained not childish but fierce as children are, and we were all her cubs and felt it. I hope that it is no shadow to Mrs Brunner’s own daughter to say that Mrs Brunner made me feel, if not mothered, protected.

My friend Rosa was a fellow of Brasenose. My friend Fram Dinshaw, whom I’d known since I was less than twenty, was a fellow at St Catherine’s College. My friend James Fergusson was working at an antiquarian bookshop in Oxford. Jamie and the children and I would meet in Oxford for greedy Chinese lunches at a restaurant where in the fish tank were those carp whose eyes stick out and who seem to be dancing with their floating veils of fin.

Long before my first marriage, Fram had, outside Rosa’s house in Oxford, given me a kiss. Shortly afterwards he wrote to me. I read the letter standing up on the Bakerloo Line between Warwick Avenue and Oxford Circus, on my way to Vogue. In it, he adumbrated that if I did not smell so horribly of smoke he might conceivably take an interest in me and that there was something about me that reminded him of blackberries and that we might, if I calmed down, end up together.

But by now, many years later, I was a vessel with cargo, my children. All the smelling of blackberries in the world doesn’t mean that you can be careless with human souls.

Our first date, or rather what reveals itself to have been, retrospectively, a date, was to Rycote Chapel. In the car Fram put on ‘Soave sia il vento’. Later he made me a tape recording of some Larkin poems. I found myself playing them when he was not there. I listened again and again to ‘The Trees’:

Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

Once, when the children were with Quentin, I agreed to go and stay with Fram at his family’s house outside Cortona. It was to be reached by a dirt road cut into the hillside. Opposite lived a couple called Gina and Nino Franchina. She was the daughter of the artist Gino Severini and granddaughter of the poet Paul Fort. Nino made tree-sized helical metal sculptures. Further along lived a family who would prove to contain the novelist Amanda Craig, though I’ve not met her.

Early one morning, taking a walk up the lane and between the strawberry trees, I looked in the damper gullies at the edge of the dry thin path. I couldn’t believe what I saw. There they were, growing wild, those black velvet irises that I love. They were everywhere at that spot, and beyond them red tulips, with reflexed petals and thin stems like veins, which preferred to be on flatter tilth, as though they knew that they were a motif on a million Turkish carpets.

The house at Cortona was simple, two storeyed, whitewashed within and then decorated by Fram’s mother, who had a gift for drawing that had won her a place, that she did not take up, at the Slade. The house smelt of woodsmoke, lemons and basil and was set amid olive groves. It had a particularly non-Italian garden because the whole family had that passion for flowers that may have come from living beside a desert in Karachi. Outside the house was a large Magnolia grandiflora, crinum lilies grew along the front and a catalpa shaded the terrace where, in good weather, we ate outside. Troughs of basil were everywhere and ‘Heavenly Blue’ morning glory twined around the kitchen door. The rose that changes in colour, Rosa chinensis mutabilis, grew around the front door. At Easter peonies we never identified, which had come from the villa below, would flower with pink heads considerably bigger than my own children’s. The bottom of the garden was hedged with a vine of that most fragrant and intoxicating grape the uva di fragola, the grape whose taste and scent is that of a strawberry and makes a wine that for some reason the European authorities disapprove of, so it is drunk in secret among friends. Rosemary and sage and all the herbs that flourish in dryness lent their oil to the air. By the well stood a fig tree and another deeper down the garden. At the side of the house was the kitchen garden, or orto.

The family who originally lived just below and later moved into the local town still came up to work for gli indiani on the hill. Franca, the wife, worked in the orto and as cook, and her husband Guido came and fixed emergencies such as wild boar in the garden or a plumbing disaster.

Negotiations between a Tuscan peasant and a fastidious Zoroastrian, as Fram’s mother Mehroo temperamentally as well as religiously was, were nothing like as difficult as they might have been had the two women not decided that they liked one another. Franca therefore simply fitted in with what she was told, that only napkins with a person’s initial on might be given to that person, that never must bedspreads be put on a bed with the foot part at the top, that all sudsing had to be done before all rinsing when washing up, and that the rinsing must be under flowing water, that dirty utensils must never be laid down on the side but on a dish and so on. Much of it was common sense and the rest she took as part of the charm of this little family who had decided for part of their year to move into the house that had proven such hard work for her own family.

Out in the orto, copper sulphate was sprayed and dried to a high abstract blue on the tomatoes, grapes, aubergines, peppers and zucchini, whose flowers Franca would fry and scatter with salt.

To watch Fram’s mother cook was to watch an artist at work. Her fine, beautiful hands had nails like almonds with that natural line of white seen in some Madonnas. To take the bitterness from a cucumber, she would cut off the narrower end and – often gently telling one a story and meeting one’s eyes with her own – turn and turn and turn the cut piece of cucumber until it had drawn out all the bitter white milk. Then, and then only, would the cucumber be ready for peeling and for slicing into lenses as cool as ice for hot eyes, cut not with a mandolin but with a little knife. She did everything domestic beautifully so that it must have been, for her family, like living with a ballerina or an antelope, something incapable of ungrace or disgrace. She was lovely to behold. It was a quality that resided in tempo as much as in address and gave each act its own dignity. She made, rather than took, time.

When I read Edward Said’s autobiography, I was pierced by the similarity of his own relationship with his mother to that of Fram and Mehroo, though, unlike Fram, Said seemed to have established some wafer of air betwixt she who bore him and what he could bear.

Today, 5 June 2007, is a flawless high blue June day in Chelsea. Some days ago, we were puzzled as to why the air was full of low, close, mechanical noise. It transpired that the Metropolitan Police had chosen to shoot a young man, unhappy in his marriage, desperate for the return of his wife, far gone in drink, and wielding a gun with which he could have killed no one. The police marksman shot him in the head; that is, he shot to kill. What of talking to him? What of tranquillisers? That young man might, a hundred times, have been me.

It is when such things happen that people around my age thank God their parents are dead.

Last night I had a visit from the film-maker Amy Hardie. We have a friend in common and she was keen to tell me about her experience of a shaman in Edinburgh, who she believes has saved her life. She feels that my eyes might open if the doctors could be more humble and eclectic when it comes to the hidden paths of the human brain. I had wondered if I blinded myself when I left Fram, whom I married on 27 September 1986. I left him in November 1996.

The onset of the physical condition, ten years later, seemed like the reification of a metaphor I had inhabited for a long time. This way of thinking enraged the more mechanical of my doctors.

Amy’s film threw me back on the dear dead. When I was drinking, I summoned them and held long conversations with them; I could actually see them. It was a solid experience. Among my dearest dead is Fram’s mother. You might say that it is easy for me to love her now that she is dead, but we do not love the dead on account of the relief they offer us but on account of the personality that has gone for ever. My mother-in-law was one of those who can turn a room to flowers and air or fill it with frost and razor blades. It gave my mother-in-law pleasure herself to give pleasure and yet sometimes something dreadful took and squeezed her. The persons who most understood, loved, overlooked and steadied this were her doting, hugely intelligent, husband Eduljee (Eddie) and her daughter Avi.

When, as a family (which is what I then believed we were), we visited Karachi, it was a time without flaw. Of course the city itself was growing more dangerous and I did not leave the house alone since in myself I constituted a western cliché, with my yellow hair and pink face, maybe even an affront. Fram’s childhood house had been eaten by white ants, so the Karachi house was built, oddly enough, by a Scots architect the Dinshaws came across who was working for UNESCO. The house dated from the nineteen-sixties. It was set around a cool quadrangle where we took tea and batasas, a kind of dry, cheesy, Parsi shortbread. The years fell away from my mother-in-law. Her husband’s sister was in Karachi at the same time with her family and there was much toing and froing, not quite the same as living in the extended family system in the Indo-Italianate villa of Fram’s grandparents that had been sold just that year and which we visited one day for tea.

We drove up past lawns edged with bright red bedding-plants to the façade of this house near the Victorian Gothic Frere Hall in the middle of old Karachi. We mounted the stairs, and in contrast to the other houses we visited during that happy fortnight, encountered the electric interference of modernity. Every room was dominated by a telly and video. There were at least two sons of the house, under ten and chubby. We took tea and talked. There was a year’s worth of Karachi gossip to catch up on, although it was not the inner gossip of the Parsi world. There was talk of conditions worsening in the city, of men with guns at night, of the chowkidars having dreadful fights. On a table to the side of the room reposed a selection of small-eats, or rather enormous and challenging cakes, clearly as much for show as for ingestion. I noticed that the chubsters had disappeared. The table that bore the showy cakes had a nice hand-blocked tablecloth that fell to the floor. It was a homely touch in a house otherwise fitted out by Sony, Sanyo, Bang & Olufsen. The chocolate cake was the most splendid of all, turreted, godrooned and melting. The attack it was receiving from the warm day, despite the chattering air conditioning, was being assisted by four hands that were hollowing out the cake from under the tablecloth with quite as much assiduity as if they had been white ants.

Fram remembers the mango tree in the garden of the house of his babyhood where he was born at Breach Candy in Bombay, within sound of the sea. He used to say that he was the monkey who played and ate and swung and made himself safe in the branches of me, who was that fertile, glowing, mango tree. How can I have taken an axe to its roots?

Back in Karachi, where my parents-in-law had made their first marital home, I had the sense that my mother-in-law was so secure that she could trust me. Her lifelong servant, Munsuf, served us at meals with a different cockade in his turban depending on the formality of the meal. I learned a, very, little Urdu because Munsuf was Muslim and I wanted to make it plain to him how happy I was to see him and the family at home. He began to work for my mother-in-law when he was still a boy and she not that much older, so their closeness was telepathic. One afternoon, my mother-in-law relaxed with me enough to show me her saris. She shook out each one and told me when and where she had worn it. In a woman so averse to show yet so sensible to beauty, this was the showing of a miles-long florilegium. The saris were stored with balls of cedar wood and muslin bags of lavender that she had grown in Cortona. Each sari was a woven story and there was what she didn’t say too, which was that she loved and quite clearly looked beautiful in that pink which is almost blue and that I particularly love; it is among the last colours to fade from flowers at twilight.

My father-in-law read the Dawn, Karachi’s newspaper, daily, and looked, as he always did, at the stock-market prices. In the evening he was reading Flaubert’s letters on a small upright sofa in the drawing room. The routines of daily life were congenial, airy and natural between each of us, I believed, at the time.

One night, because we were young, Fram, his sister Avi and I and their cousins were invited to a beach party. Many aspects of it were curious. The young women whom I had met as Parsi wives and daughters, ravishing in the modesty of their garments and the flat shine of their Indian-set jewels and pearls, had changed, since it was night-time and no one but their husbands would see them, into western beachwear or into some designer’s idea of western beachwear. Many of these couples, after all, had houses in New York too. We were driven along the spit out into the Arabian Sea where I doubt that anyone much keeps a beach house any longer, but in those days it was like a more expansive Southwold. The servants settled to making the barbecue and the wives to comparing their outfits. How much lovelier, actually, they had looked before. Nonetheless their husbands seemed pleased to see their wives turned out so with their crazy sunglasses – although it was pitch black outside – and marvellous sarongs covered with logos. Even the jewellery had changed and become the faceted hard jewellery of the West.

Yet perhaps they were right to be so strangely attired and that only for the cover of night, for it was to prove to be a night of nights, the night when the turtles know to emerge from the edge of the sea and un-dig from the sand the clutches of leathery eggs they have left there.

So there we were, all of us quite young, and everyone apart from Avi, Fram, their cousins and myself, dressed for a blazing day in Portofino, when out of the sea came lumbering animals large enough to ride on yet made almost completely of horn and leather, tanks on the sand, ballerinas in the water. Then it began. Hundreds and thousands of perfect models of their mother, but the size of a Jaffa Cake, came scrobbling out of their nests and hurled themselves into the sea, which indifferent, hauled them in its wave further up the beach to leave them high and dry. It proved to be a whole other way in which you can’t beat the sea. We picked up handfuls of the perfect, scratchy little things and went quite deep into the sea with them, but back the waves came with their freight of bad pennies. Exhaustion killed many; it’s not surprising to learn that so few survive.

While working in our high cliff of a studio, Liv and I are receiving more visitors than we used to, because this handsome, crumbly house is about to be taken to pieces and put together again. Contractors, builders, civil engineers, architects, curtain-makers, come and go with their laser tape measures and their pickaxes. We are polite but so far haven’t offered tea. We are working too.

So if I felt that I was contingent and perching on a small ledge before, I now feel the ledge is thinning and the sea beneath me is crawling, and I must get on with this story.

When we were nineteen or so, I knew from his appearance, which is elegant and slender, and from his colour, which is a light caramel brown, that Fram was not English. I assumed that he was Indian. He is in fact Parsi. He is a Persian, descended from that group of Zoroastrians who, at the time of the Arab invasions, fled from Iran in boats and landed in Gujarat. The Parsis made a deal with the indigenous ruler, fortunately for them a Hindu, that they would neither break any of their host’s taboos nor proselytise. In return he allowed them to settle and trade, originally in a kind of palm toddy. During the time of the Raj, Parsis found a thirstier market, purveying whisky, brandy, soda water and so on to the sahibs.

Zoroastrianism seems to me, who have less than no business to opine, but a Zoroastrian son, a commendably rational way of leading a life. That son, for example, really does implement the instruction left to him by his Parsi grandmother on her deathbed, ‘Good thoughts, good words, good deeds.’ It is a religion that institutionalises charitable giving and that reminds each member of the faith that he has brought nothing into the world and will take nothing out. Each Parsi wears a thread around his or her waist called the kasti, as a warning against excess; below the normal daily shirt of even a westernised Parsi you may find a sadra, which is an almost gauze-like vest of simple white muslin to remind the wearer that, no matter his prosperity, he is the same as any other man.

It is an ancient faith and I feel shy writing anything about it. However, its importance in my life cannot be overemphasised, both for good and for, entirely unintended, harm. Perhaps the thing that most outsiders know about Parsis is that they bury their dead on Towers of Silence, leaving them there to be eaten by vultures and returned, therefore, to the cycle of life. The other thing that people know about Parsis is that they are worshippers of fire.

There is in the world a dwindling number of pure Parsis. This is not helped by people like me, who have married pure Parsis. There has come a ruling from the Parsi Panchayat, the ruling body, that the children of male Parsis born to farangi women may still be Parsi, but this is not entirely popular with ultra-orthodox believers. One may read frightening things on websites. It all returns to the cruel question of purity, an inhuman phenomenon that is presently igniting all flammable faiths, creeds, tribes and dictators as it has immemorially done. Purity posits the notion that we are not one another; whereas clearly, to live, we must imagine how it is to be one another. This is where fiction, though it is not a utilitarian art, or anything so simple, cannot but come in. We need urgently to know how other people feel.

The closeness and decency of the Parsi community, insofar as I have ever encountered it, comes as refreshment to the soul. There are fewer than 100,000 Parsis in the world. Zoroastrians have been actively persecuted in Iran, and in India a really unexpected modern glitch has compromised their ancient burial customs. Indian vets have begun to treat ailing cattle with Voltarol, a painkiller that – if they eat one of the treated cows – attacks the liver of Indian vultures. The vulture population of, for example, Bombay, has dropped by ninety per cent, which presents a public health hazard and portends disaster – or change – to the Parsi community as it holds up the liberation of the soul and the rejoining of the body to the creation.

In fact for the last two generations, Fram’s immediate family have been buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome. I am glad of this in some cowardly ways. The thought of my shrouded husband or my son in his cerements being loaded on to an aeroplane to be taken to the Towers of Silence, where women may not enter, is a lonely one. Lonely for them, I mean.

So how does this relate to Rycote Chapel, with its stars cut out of contraband playing cards on the ceiling? I had always known that Fram was clever and could be exceedingly cutting. What I had not expected was a complete unevasive answering of every question I had asked or even thought to ask. I think that I knew I loved him when he referred with exotic normality to Marks and Spencer as ‘Marks’.

I thought, here is someone with a perfect ear for seventeenth-century poetry, here is someone who never misses a trick, here is someone of whom I was afraid because I know his tongue has blades, and yet he is still, despite all his schooling and conditioning, that tiny bit unassimilated. All children brought up between cultures become felinely bilingual, trilingual, whatever it takes. Fram had in his time acquired illiterate smatterings of Urdu and Gujarati; more Latin, less Greek; French and Italian. His English modifies according to with whom he is speaking, so that when on the telephone to his parents, whose English was the hyper-English of let us say, the Third Programme in the 1960s, you would hear that note leaking into his own tone. When he is with his sister, they speak English at one another like birds. When he is teaching or giving a lecture he speaks naturally in a pure Latinate English and in paragraphs. I love his clarity. When we talk, I wave the butterfly net; he does the pinning.

Very slowly, and it was slow because the children were my main trust, I introduced them to Fram, mostly with Mrs Brunner or someone else there too. He was, at that stage of his life, as he expressed it, ‘agnostic about children’.

The curious thing is that while Fram was not disinclined in principle to undergo an arranged marriage should his parents wish it, and despite there being one candidate who sounded suitable and lived in Paris, his parents never did arrange such a match. For as long as possible, his mother ignored the fact that her son might be having relationships with non-Parsi girls, for so he was. His taste ran to beauties; quality not quantity was the characteristic of those who might be found in his sway. But somehow he managed, throughout his twenties, to remain the apple of his mother’s eye, unpunished as yet for having grown into manhood.