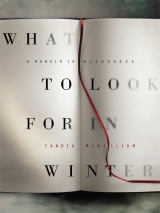

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Meanwhile, happier news was coming from Farleigh. I had been nervous lest some hard-faced blonde direct herself at Quentin and the children, but I should have had more faith in him. My old friend Jamie Fergusson had introduced Quentin to his cousin Annabel, I believe on the Isle of Wight, maybe even over a bucket and spade. I do not know where to begin about Annabel. She is the A to his Q. But how was it then? Was I jealous to hear that Quentin had a friend whom he had introduced to the children? I was not. I had known Annabel since I was about seventeen and much liked her parents. Her father was a general physician in Richmond, one of the old school, who wore striped trousers and a black coat. He was very funny, but you had to wait for the jokes, because, like his brother Pat, the father of Jamie, he spoke incredibly slowly. I once missed an aeroplane because Pat Fergusson enquired over breakfast one day when I was due to fly to Glasgow, ‘Whether……….or………not……………you…………are………………an…admirer……….of……………the………………novels……. of…….Ivy Compton-Burnett?’

One of the treats available to a Fergusson-fancier, when the two brothers were still alive, was to get them together and overhear their conversation. It was like waiting for the Mona Lisa to wink.

Annabel’s mother is something quite else. Spirited, croyante, a Catholic convert, she is one of those people very much one’s senior who combine wisdom with knowing exactly what’s hot at Top Shop. I loved her from our first meeting, which was long before anyone in our generation had married anyone.

Annabel herself I first met at a party where what was striking was the blueness of her eyes, the grooviness of her physique and the old-fashionedness of her garb. I think maybe at her christening there was a fairy who arranged for Annabel to dress in an especially old-fashioned way, otherwise her effect as she walked down the street would, like that of Zuleika Dobson, have left men even more stupefied than they already were. The other thing I knew about Annabel was that she was clever in the practical, realistic way that I am not. People would say of her, ‘She looks like a Botticelli angel but do you know she can do the Times crossword?’

No one could possibly accuse me of either of these attributes and I was happy that Quentin himself might be growing happier. I also knew, most importantly of all, that Annabel was kind and good. Later it was my pleasure to find that she is really, properly, funny. It’s like medicine.

For reasons to do with the house at Wotton’s beauty and Mrs Brunner’s scarcely perceived but very present hand on the tiller of the life that my children and I led, we never felt transient or uncared-for. She combined bossiness with affection and the sort of over-partiality you do, on the whole, only offer to your kin, so that we did feel we were living with, if not a fairy godmother, a fairy grandmother.

I hate competitive games, maybe for the base reason that I’m no good at them. At New Year, Mrs Brunner, who had an entire room called the Oak Room dedicated to stage costumes, held a charades party. How I dreaded it. I can’t act to order and I can’t act if I know I’m acting, but I loved her and would have to attend. I couldn’t pretend I had to stay with the children because they were with Quentin, and Fram was with his parents because New Year’s Day was his father’s birthday. (Parsis have two birthdays, one dependent on their mama and one dependent on the moon.) Mrs Brunner had arrayed herself that night as a mixture of Catherine the Great, Elizabeth I, the Empress of Bohemia and all nine muses. Her golden hair was up, her face painted. It was possible to see the captivating young woman she had been. But in this incarnation she was authoritative.

The script was complicated, a good dinner had been had, much Champagne drunk, a charming set-designer named Carl Toms, who had worked with Visconti at Covent Garden, was on hand, while to direct us there was none other than Nicholas Hytner. I’m glad to say that he recognised my acting potential at once and that I played my part as a poisonous mushroom with the sort of grace and sporingness you might expect. New Year was also the birthday of Annabel and I believe that it was then that Quentin proposed marriage to her. I hope that I am right. Perhaps I am giving them a few more years of marriage than they have had, in which case, lucky them.

In the case of Fram and myself, things could not but have been more complicated. When I consider myself from my mother-in-law’s point of view, I can see that what her beautiful only son was bringing home was a gigantic, Angrez, previously married, too old, and completely untrained animal. My mother-in-law could not help feeling these things. In complex ways, the West that she had been raised to admire, whose literature had arrived by steamer-trunk throughout her children’s childhood, had become grotesque, appetitive, grasping, vulgar. The particularly bad part of it all was that I entirely saw her point of view and agreed with her, so replete was I with self-disgust, self-distaste and the willingness to believe that I smelt and took filth with me wherever I went. It was an unhappy concatenation.

My father-in-law Eddie, who I always thought liked me a bit more than did his wife, actually liked me a good deal less.

Nonetheless, all these feelings were, for some years, hidden by my parents-in-law. It might have been better to have released them by some means other than the slashes of the razor that my mother-in-law chose as her means of attack. It was mainly her son she punished. Yet they themselves had been to school in England, had sent him to prep and public school in England, so to punish him for being what she called a ‘brown Englishman’ was cruel. She never stopped loving her son, so the hurt she felt compelled by her anxieties to cause him harmed her much more.

My mother-in-law was a woman who could make a room a paradise or a slicing unit on account of her mood. Her family were used to it. My sister-in-law Avi, who stands at under five foot and has known severe long-term medical pain in her life, simply and beautifully neutralised all malice ever afloat in the room by her own blessedly even nature. She has a keel. I don’t know if it’s a faith or her natural acceptingness, or both.

I fear that I was all too keen to condemn myself. At the very beginning, when Fram first courted me, I think my mother-in-law and I wanted to love one another; I certainly wanted to love her. I think she genuinely tried to love me, but my own sense of my unloveability rushed to greet her instinctive condemnation and they wrought, over the years, a terrible mischief together. In order to be married in Italy, we had to fulfil residency requirements and stay in the house in Cortona for something like two months. Quentin was happy that we were being married out of England – it seemed more natural that way.

We did have one happy day, the day of our Parsi betrothal in Cortona. My mother-in-law had threaded jasmine and marigold ropes and set in shaken chalk auspicious designs all around the perimeter of the house. Fram’s aunt and uncle came from Rome, a coconut was broken and rice placed on our foreheads and sugar on our tongues to make sure that we would only speak sweet words to one another.

The wedding itself took place under the aegis of the Communist Party of Italy. The Mayor of Cortona made us freemen of that beautiful town. We were garlanded with long strings of carnations that my mother-in-law had sewn. We were young, thin, blazingly in love and tremendously close at every possible level. There was a feast at Vasari’s house outside Arezzo, with Italian and Indian food alternating. Fram’s kind and smiling Aunt Khorshed had provided Niazi, her old cook from the Pakistani Embassy in Rome. Yet in the photographs my mother-in-law is holding her sari over her face so that she cannot see what is being enacted before her. If only I could have taken that pain from her and told her that I would look after and love her son for ever, that I could love her, that I was I, not a foreign culture. But it didn’t happen.

Months later, after our honeymoon, the photographs of our wedding came back and Fram noted on a visit home the distaste with which they were regarded. The poison had started to run and could only get worse, most especially when I began to make some small name for myself in that thing, the world.

Mrs Brunner had been simply furious when we got engaged, though it was in a direct and catty way and once she’d said her dreadful piece, we did make friends again. What she said to me was, ‘Go and live with an Indian beside a bus stop in Oxford.’ But in the end she was tremendously chuffed by the next lodger I was able to conjure, up to whom I could not come in any regard, for he was a boy and a handsome one and Mrs Brunner saw at once that here was something greatly more glamorous than I, Edward St Aubyn.

We settled into our flat by the bus stop in the Banbury Road, and I remember Brigid Brophy sending me a postcard saying that to live on the Banbury Road must be much like living in Persepolis. In several regards she can’t have been wrong at all, for I did indeed try hard, and mostly failed miserably, to keep a Parsi house. Even though my mother-in-law chose the sinks and all the sanitary ware and I never cooked onions because Fram hated the smell, I did not keep a Parsi house. My hair moults and Parsis have a horror of dead hair, wrapping it up before throwing it away, as ‘we’ might and ‘they’ certainly do with nail clippings. It was, of course, idiotic to attempt to ape a culture I had not been born into, no matter how open to it I was – and I was. The cracks in a performance, no matter how rounded it be, will declare themselves, through nerves, self-consciousness, or even that sense of falsity that goes with the attempt to imitate, be it never so innocent and good-hearted. How could I, brought up in Edinburgh, gather what had been handed down through thousands of years from the high plains of Yazd and Bam?

The following awful truth is so. My father was expected at our wedding, but mysteriously cancelled. On our wedding night, over dinner in Orvieto, Jamie Fergusson casually let it fall that Daddy was that day having open-heart surgery. Later that night, before retiring, we went for a walk in the town. When Fram saw someone whom he thought attractive, he said so, as he always did. I thought, ‘That’s fine. It’ll all feed back into me.’ Now I think I know that I should have said, ‘It’s our wedding night. Please look at me. I am here.’

I learned these things too late and from Fram’s new companion Claudia, who has only just not got my name. She enacts these things and is in this respect my beneficiary, as well as being someone who knows instinctively how a properly adjusted person should behave.

Having been raised in habits of unassertion, I have learned inadequate systems of self-defence that may seem suspect to outsiders especially when manifested by a person of such size.

There is on the face of Orvieto Cathedral one particular dancing angel, her mood choric, her hair loose, her mouth laughing. I did feel that happy on that first day of our marriage and often thereafter too.

Our honeymoon was short and busy. We drove the elderly white Lancia on which Fram had learned to drive in The Hague fifteen years earlier, when his uncle had been Pakistani Ambassador. You could see the autostrada through the floor. We drove south to Ravello and Amalfi. Lorna Sage had given us Gore Vidal’s telephone number and told us he’d love to hear from us.

Not much he didn’t. At Fram’s amused insistence (maybe he was bored) every day, after caffe latte and for Fram toast and croissants (I was constantly, in those days, starving myself) I would ring the Vidal house and get a very dusty answer indeed. We drove to Pompeii, Herculaneum and very early one morning Paestum where the air smelt of sage and rosemary and our only companions were two ghosts.

The ghosts were tidy and well turned out, clearly having died around the mid nineteen-twenties. Her bob, her filet, his hat, his pince-nez, their faded Baedeker, his ancient plate camera, her button shoes, her clocked silk stockings, his punched co-ordinate brogues, everything chimed. It was years later in England that we realised that they must have been Stephen and Oriel Calloway, doing a spot of rubble-romping.

It was Fram’s first sweet act as a stepfather that our honeymoon lasted only four days because we had to surge up to Rome again and fly home so that we might take the children to be page and bridesmaid at the wedding of our friends Cyril and Natasha Kinsky in Dorset. There was no grumbling at all and I recall, as the dancing began, having a sensation that should not arrive as a form of self-consciousness, since it is an absence of self-consciousness, that I was where I should be, with whom I should be. It was wonderful to be with the children again.

There was from the start something not good for our marriage in the routines that I collaborated with. Because I had never forbidden anyone anything, I encouraged Fram to spend as much time with his mother as he had when he was a bachelor, rationalising that this was an adjustment that I had to make as the junior partner (junior to my mother-in-law) and in deference to her increasing sense of alienation. I was atoning for the Raj, perhaps. I don’t know how. It is interesting that she had a Scottish governess. When she visited Edinburgh, long after we had parted, she said that it could have been somewhere she might have lived and that she wished she had seen it and understood before. This is very sad to address for me.

Her home, or any full concept of that home, had been ruptured by the Partition of India in 1947, the year of her marriage. She and Eddie were first cousins, but his father came from Karachi; hers from Bombay. They had married entirely for love, but the romance had been furthered by their common (Bombay) grandfather. It was an unusually tribal hybrid: a love match that might as well have been arranged. My parents-in-law were everything to each other and regarded their children as extensions of themselves. They began to pity Fram for not, apparently, conforming to their model.

My in-laws’ distaste was certainly not helped when it came to my first entering the world of being published. The Common Reader had all but died out. Publicity was in the ascendant, about to gain a grip even on the then fusty world of publishing.

Such was Mehroo’s charm, and so profound my longing to have a mother figure to love, that I often felt it could have come right, but she was undoubtedly massaged in her nascent, perhaps at the time only half-formed hostility towards me, not remotely by the family in Rome who were steadily loving, but perhaps by others unseen by us. Someone certainly ensured that my poor mother-in-law received every single press cutting referring to me. The sophisticated reader (and my mother-in-law was sophisticated until blinded by emotion) will realise that one has little control over how one is depicted in the press. When my first novel came out, there were a number of photographs of me, none indecent, but very few in my own clothes. I stayed with my in-laws while being photographed by the late (and notably serious-minded and intelligent) Terence Donovan. They were appalled at the stylist’s contrivances when I returned after the shoot. Fram was later given to understand that my painted presence would discomfit his father in his immaculate dressing gown over the breakfast table.

When it became clear that I was having a baby, we went to tell my parents-in-law the happy news. Something was very wrong in the atmosphere of the flat. My mother-in-law made what was meant to be an overture of friendship, but said something on the self-deluding lines of ‘Can’t we agree that these misunderstandings have all been Fram’s fault?’ I stiffened and could not agree. The atmosphere rapidly soured. Doors opened and closed; hurried consultations seemed to be taking place in other rooms. But whatever the thing was that I was missing or catalysing, I could not identify, nor would for many months later. My father-in-law had just been diagnosed with leukaemia and my mother-in-law in some measure associated this with a piece that had appeared in the Daily Mail about a German literary prize that I had won that made some ribald play over lederhosen. A kind friend had sent her a cutting.

Our son was born at 4.03 p.m. on 22nd February 1989. Fram was at a meeting in College. The baby lost oxygen at the last minute and arrived blue. A very smooth gynaecologist whispered the word ‘Resuscitator’ into a kind of grid in the wall and then the room was full of focused people doing the thing they had practised to do: to bring back life. Minoo changed from navy blue to mauve to almond brown. We met, liked one another on sight (I can speak for him too) and were at once separated to our respective units of intensive care. I had lost so much blood that they wanted to give me a transfusion. Luckily my blood slowly made more of itself. I was already making those deals you make when it is life or death. We were gently told by the well-meaning wife of a colleague that Minoo might never be mentally or physically quite right. My parents-in-law visited Minoo in intensive care, peered through the glass wall and noted with some relief that he looked very much like his father. I was not surprised that they didn’t come and see me. They would have characterised it as not wanting to disturb me. Now, almost twenty years later, I think that there should have been less of that sort of stuff in my life and that my son’s grandparents should have come to see his mother who was also, perhaps, in some danger.

Fram went home and prayed hard all night for our small son. In Italy while I was pregnant we had toyed with naming him Bruno or Gabriel, but, and I think this is quite right, the moment he was born it became clear that he should have the customary Parsi names: his great-grandfather’s, his grandfather’s and his father’s. So I have two sons whose names were foreordained. I have never minded this in the least; their names fit them like gloves. The birth of Minocher Framroze Eduljee Dinshaw was announced in the Telegraph, I suppose, and maybe The Times. It was also, thanks to the ignorance (let’s be gentle and not say racism) of Private Eye, announced in Pseuds Corner, as bearing witness to the fact that my pretentiousness knew no bounds, since I’d even given my infant son invented and show-off names.

For some months after his birth, we took Minoo for check-ups, and he learned very late to sit up. It’s certainly true that now I have Minoo, I believe that dyspraxia is real, not just a newfangled term for clumsiness. But those prayers Fram sent up seem to have achieved something. Minoo will never make a waiter or a footballer, but his brain functions, may the saints preserve it. He is presently exercising it swotting for his Mods at Balliol, having long outstripped, in literary terms, his exhausted mother. His brother and sister met him with the gentleness and curiosity towards babies that are characteristic of their own father.

LENS II: Chapter 8

Just in time to start this section of writing, two things happened. My eyes closed down and the doorbell went. Liv helped me to pack away the typical over-reaction that I enact whenever I have tidings that a child may be looming, in this case Oliver. I will not show him all that he is expected to eat or I will receive a well-made and entirely merited lecture against stockpiling perishables in an under-performing economy. I just want him to have the right level of bake to his water biscuits, the right absence of bubble to his mineral water, the correct ratio of cocoa solids to his dark chocolate, and of course the all-important mint tea bags, since he regards fresh mint tea as less satisfactory than the enbagged product. So, you might reasonably suppose, isn’t a woman who is this pedantic about her son’s grocery welfare set fair to be a hellish mother-in-law? I do hope not, and most of it, my intensive pampering and consideration of my children, is as it were love in microdot form.

So why did the lids over my eyes glue themselves together just like that when it’s an Olly day and Liv and I are, I think, quite relaxed together? The only reason I can adduce is that at the age of thirty-six, my mother decided to stop right there, just like that. Had she lived, she would be eighty-one, an auspicious number for Orientals as it happens, since it is divisible by three and compounds of three. I cannot imagine the sort of old woman she would have been, though I am fast imagining the sort of old woman that I shall become.

In fact, anatomically, I feel that I have become that old thing. I creep, I peer, I fall. I have very nearly forgotten how it felt simply to stride along a street with one’s head back and one’s hair falling down one’s shoulders. Yet this feeling was mine not two and a half years ago. I have become timid, from a very low base, since I was already really laughably, in many areas, psychologically timid.

I remember at my friend Alexandra Shulman’s twenty-first birthday party a wild Irish boy called Connor said to me, ‘You’re no use for anything but tossing your hair and making big lips at people.’ It looks as though he was right, in a way. Certainly I bear him no malice because he was one of those characters who bring event and warmth into a room, a plot-turner.

My father’s death was sudden too, like my own coup de vieux. My stepmother telephoned. I picked up the phone. The children were all three one room away. My stepmother’s clear tones said what she had to be ringing to say:

‘Oh Candy, it’s Colin, he’s died.’

I said at once what the celestial scriptwriter told me to say and replied, ‘You were a very good wife to him.’

My stepmother explained that essentially Daddy, exactly like Quentin’s father, had burst, his pacemakered but weakened heart haemorrhaging in that slim chest, and gore pouring from that witty mouth. Fram was in Jersey with his parents. I insisted that he should not cut short his weekend. They thought this odd and were uneasy. I told myself that this was selfless, that there was nothing he could do for me to bring my father back, and there was plenty he could do with his parents on Jersey to make them happy.

There was of course a baser motive, the motive that had been pulling me into quicksands ever since my twenties. If Fram were not with me in my misery, I could drink, and drink I did.

We were already at the time seeing a psychiatrist about my drinking. He was expensive but good. From an orthodox Jewish background, married to a black woman, he had experienced much that was helpful to us when it came to the atavistic flinch. Yet every time we visited, I wasted at least three minutes by making the ‘I know we’re lucky’ speech, the speech of guilty shrink-attenders everywhere.

By the time Fram returned from Jersey, I was the sort of drunk that he must, each time he approached our house, have learned to dread. I was a talking doll with a small vocabulary and stiff limbs. My brain, my spirit, my soul and my spirit-sodden body were unavailable to him at this most dreadful time, when he would have known in every wise how to calm and console me.

Five days later we left the children for the day with a babysitter and of course a list of telephone numbers. We drove to Heathrow and entered the aeroplane in our dark funeral clothes. At the then friendly and rather cosy part of Heathrow where one used to embark for Scotland were further mourners including my cousin Frances and Jamie Fergusson. Frances had been evacuated as a child to the house where we now lived in Oxford. She had known it as the house of one family. We knew it divided up by a developer; our kitchen was the old butler’s pantry. Frances had particularly disliked my first novel and wrote me a long letter explaining why, resting her case on the reasonable enough complaint that there are sufficiently many nasty people in the world without writing about more. She also very much disliked the business of my drawing attention to myself by being published. Nonetheless, she made a gay-hearted and kind companion during the long cold exhausting farce that was to be the day of my father’s funeral. In the morning I had rung a florist and asked for a big bunch of mixed anemones to be placed on his grave, with a note saying, ‘To Daddy, with all my love from Candy’. Once in the air, we felt all set for this impossible event, Daddy’s last ever slipping out of the room. Considering that he was only just sixty-one, what a lot he did with his life. He’d meant to die. He hated falling to bits.

We sat with our thoughts. Jamie is perfect at these occasions and knows to tease me but not to make me cry. He had written a personal obituary of my father for the Independent in addition to the official art-historical one.

Over the border, something started not to go quite right. Our captain came on to the public address system. Lovely, reassuring doctor’s voice. We were in the middle of a blizzard that had suddenly burst over Scotland and we would have to divert to Glasgow.

The funeral was in Edinburgh.

It was a bumpy flight with much flashing in the air and sudden darkness at the windows. I wondered if Daddy had anything to do with it. When at last we got out at Glasgow, we were faced with really only one practical possibility, to hire a cab and screech along the M8 motorway. We got out of Glasgow’s tentacular ring-road system, with its tall noticeboards reminding you in twinkly lights not to take a drink or smoke dope at the wheel. The motorway was completely blocked and the visibility was, exactly as my father would have liked it, minimal. There was a good smoky fog. Obviously he was going to slip away while the going was good. We had already overshot the time for the commencement of the funeral service, which was to be led by the Bishop of Edinburgh, the Father Holloway of my childhood. We drove cautiously – no screeching possible – over what was nothing less than thick black ice. No one was crying and I knew that if I started to, everyone might.

On the radio, Radio Scotland reiterated news of the sudden descent of a blizzard across the central belt. I was trying to think when exactly Daddy would be put into the earth. Frances was in the front seat, Jamie, Fram and I in the back. Blizzard lights over the road kept us aware that we were in ferocious rather than merely dim conditions.

As I had so often done as a child, I leaned my head against the window and listened to its hum. I cleaned the window with my cold fingers. There, to the left, reversed out as though in a print or a linocut, was a black horse galloping across a white field, with above it, on a hill, the thorny crown of Falkland Palace. Somehow, we had got lost. I felt that the horse was white, the field was black; the message was that my father was free. His contrary soul, his dear soul was free.

We arrived in time for polite drinks at Edinburgh College of Art and I was cornered by a girl who told me, at length, how dreadful it was for her that my father was dead. I agreed but couldn’t do much more to comfort her. She had clearly enjoyed a unique relationship with my father. That’s the charm problem. The last mourners left. Edinburgh College of Art’s staff annexe seemed, once empty, a cheerless place to have travelled so far not to see the last of one’s remaining parent. Jamie and Fram suggested that despite the thick snow, we go and find the grave at the Highland Kirk of the Greyfriars where Daddy is buried close by Robert Adam. He is memorialised in the Flodden Wall of Scottish Heroes. We set off almost skiing downhill in our thin wet shoes.

Lightly clad for a southern funeral as we were, we slithered and slopped and froze. But at last we did find the fresh earth, snow-blanketed now. And we found my cheerful anemones with their card, ‘To Dad, from Mandi’. The ‘i’ had a special dot on it like a Polo mint.

Most things about this vexing day would have been to Daddy’s taste.

In Edinburgh, which, to me, has always been an hospitable city, we could not find even a cup of tea. We returned to the airport, flew back to Heathrow, said our goodbyes and Fram and I returned home to Oxford where my older children had for the first and last time comprehensively destroyed their bedroom, very possibly egged on by their grandfather who was making such a spree of it.

When I undressed the baby he had a horrible welt, open and sore, on his left-hand side, the size and shape of an adult man’s thumb. I enquired of the babysitter what it might be. ‘It’s impetigo,’ she said. ‘I have it all the time.’

Apart from – and it is a very considerable ‘apart from’—those weekends when Fram was with his parents and I therefore corroborating to myself the unlikeability my mother-in-law sensed in me, we were often very happy. I have been close in the mind to no one unrelated to me by blood as I have been to Fram and in all other parts of our lives that remains true also. Every day when he dropped me at the market to choose our dinner while he drove off to work, I thought, ‘This is how it is and this is how I wish it to be.’ I worked hard and loved it.

Our joy was later increased by the presence of Clementine, who had come to the Dragon School in Oxford as she had outgrown her school in Hampshire. This thrilled me for all the obvious reasons, and also because it had been Fram’s idea and indicated trust between our two households, Quentin and Annabel’s and ours. Clementine proved to be a fire-breathing dragon. Soon she was in the scholarship class and schoolmates with exotic names were sending her Valentine messages. Her literary tastes grew. She loved A House for Mr Biswas, finding the episode where no brown stockings are available very poignant, and reading A Suitable Boy round and round.