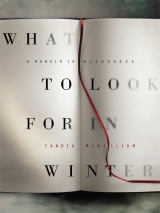

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

LENS I: Chapter 8

I do not need to invent her because I can see her in the children. She had a terrible temper, slanting eyes, outrageously long gesticulating hands, cheekbones like a Russian, a faint overbite, too much height, a silly voice, a gift for making rooms and occasions with nothing more than, say, sweet peas, a matchbox and herself. She put nasturtiums in salads, she was unnecessarily kind, her heart was tender, she got things a bit wrong and said sorry, she held her hair up with paintbrushes, she shouted, she gardened passionately and hopelessly, she loved peculiar expressions—‘touch not the cat’—and was irresistible to old men; she was a bit of a snob, she had beautiful shoulders and threw bits of cloth round her home and herself; she gave too much away, she tried to save the lives of shrews, birds, mice and tramps by bringing them home, she had an extra-ness that some fell for and some resisted, she cooked on her budget as though for a family of eight, she turned heads and ended up talking not to the prince but to the scarecrow; she was untidy with spasms of obsessive reordering, she collected small heterogeneous things as though her life depended upon it; she remembered names. She wrote rather good doggerel. The nearest thing I have to a suicide note is one such poem. I cannot hand on the misery by sharing it.

In aesthetic terms, then, she hadn’t my father’s unerring line, but she did have colour. She loved magazines, as I loved comics. She longed to subscribe to the (then) French magazine Elle; her first copy of it arrived the week after her death. I would have tea with other families because they took comics. Fat use I was as a playmate when all I did was lie on my tum and read comic strips about large families in the midst of a large family, like the Mitchisons who had an au pair and Patum Peperium for tea, or the Michies, who were Communists and had a nanny and had married one another twice and were to die together in a car crash in 2007. Then there were the Ordes who lived at Queensferry and sang madrigals and whose mother herself was so beautiful that she made cakes rise like her golden bun, and the Waterstones who taught me the Lord’s Prayer with ‘debts’ and ‘debtors’ in the Scots way and whose mother made me baked beans and of whom I said to my own mother, ‘Why can’t you be like Mrs Waterstone?’ in the last weeks of her life. I meant, ‘Why won’t you let me use the grill?’ or something, I suppose. God knows how Mummy heard those words.

Mrs Waterstone’s condolence letter arrived very soon. People were good to my father.

I don’t know exactly what my mother did. A pupil, some thirty years my senior, at a course I taught once told me that my mother had changed her will and my father had changed it back. What kind of person tells one these things? Another told me that she had broken up the flat of someone outside our family the day before she ‘did it’. I can’t see it. Is that the thing I’m refusing to see? That my mother was incontinent with grief during her last days? How could she not have been? Why else choose to die?

It would be frivolous to die without reason, wouldn’t it? Death is better perhaps than such consuming rage or misery.

All I want, for her, is to soothe her.

I do not swallow the ‘cry for help’ theory in her case, just as I don’t swallow the idea that she had a rotten go of flu, which she did, too.

She did not want to wake up on the following day. That day was to include events that she could not countenance.

I don’t even know if suicide was legal when she did it, or where her ashes are. I think she died in October. I know that I wore school uniform to the funeral and that I was horrified by the tidy curtains as she went away through them in her coffin. My friend Janey Allison, Janey who had never joined the anti-Candy gang, who grew up to be champion downhill ski-racer of all Scotland, and who could like Paul Klee hold a line boldly, in crayon as she could in snow, Janey’s mother cried at the funeral. She was a terse Scots blonde, Mary, née Ingalls, who was given to ticking us off in Latin at table in the farm kitchen out at Turnhouse, but she showed an affection I cannot forget. Janey I never see nowadays but can, right now, in her button shoes, aged four, or in her ballet gear, with the petersham belt. Our mothers were such friends as I hope we are still.

Mummy put me to bed in her and Daddy’s bed, and she told me that she loved Daddy. I have no idea whether she got down the pills, which were transparent and turquoise, with alcohol. Their name was Oblivon.

The next day took one of two forms.

Either I was taken to the home of the Professor of the History of Art, Giles Robertson, and his wife Eleanor in Saxe-Coburg Place, or I was taken by my mother’s cleaning lady, Mrs Stewart, whom I loved and called Sooty, to her house on an estate in Pilton. I can remember moments selected from each very disparate residence. Perhaps there were two days inside that one day. Oddly, I don’t know the year, though I think it was the year after President Kennedy was shot. I know that I wrote a long encomium to the President after the assassination, and that my teacher didn’t like the way I mentioned Mrs Kennedy’s pink Chanel suit; to mention garments was not ‘suitable’, a very Edinburgh concept at the time. If she’d known he was going to be assassinated, though, maybe she would have chosen something a wee bitty more practical? (Is this an especially Edinburgh consideration? In Muriel Spark’s The Driver’s Seat, the protagonist selects a specially non-stain-resistant dress to be murdered in.) I knew that it was peculiar, even distasteful, to think like this.

I can remember when President Kennedy was shot, and not when my own mother died?

I know. But it was so.

I knew that something was wrong when I saw my mother on her tummy in my bed. I think that she had on not a nightgown but a green wool dress. She had sewn me a pink pillow with grey kittens and pussy willow branches on it to help combat my nightmares about the Cauliflowers, who came out of the walls and stole your breath. I do not recall whether her head rested on this pillow at her end. That is all I saw, except that her head was to one side. It will never cease to appal me that my children have seen me from this angle on account of drink. How can I? How could I? How did I?

There’s nothing so dreadful-tasting that, if it is your poison of choice, will not make you take it. That is what addiction is. The worse it is, the more ‘unsuitable’, the more it seems to be what is made for you, your final course of just desserts, not someone else’s cup of tea at all.

That day, whichever day it was, that Mummy died, I waited for my father. At first it seemed to be with Sooty.

When Sooty’s husband Sandy came in from the Ferranti factory, Sooty took him into their kitchenette where their son David would sometimes melt lead to make soldiers. Sandy had braces and the family had a television. Sooty called Mummy ‘Maggie’. She said to Sandy, ‘It’s very bad with Maggie. I think she’s gone.’

Sandy had a blue shirt and the lino was like coloured pebbles. In the garden was an aviary for budgies. The kitchen furniture was yellow plastic with dots and lines in black and white. I loved Sooty’s curtains. They were printed with pictures of onions and carrots and Italian things like peppers, and implements, whisks, which we called beaters then.

Sooty let me beat up some evaporated milk till it got frothy and eat it off the spoon. Did Daddy come and get me? How much worse it must have been for him, exposed to his wife’s grief and pain for good.

How terrified he must have been. What could he do but what he did?

He told me the truth in the bedroom of the two youngest Robertson boys, Charles and Robert. We played together all our childhood, the three of us. The Robertsons were Quakers. The house, home of clever articulate children and a scholarly pair of parents whom I loved, was always filled with wonderfully tempered vocative tones of ‘thee’ and ‘thou’. Their father, Giles, was a Bellini scholar. He read to us, very fast, in the drawing room, under the Venetian chandelier. He read, for example, A Flat Iron for a Farthing by Mrs Juliana Horatia Ewing. If we grew restive, we played. Our favourite game was ‘Siesta Time on Mount Olympus’. We put on our counterpanes and played at being gods and a goddess. If we grew more restive, their mother, Eleanor, or one of the older children would say, ‘Thee must not romp in the drawing room!’

Maybe a year later I was to embarrass Charles by pretending that he was my ‘boyfriend’ so as to stop being nagged about the existence of such a person by other girls at school. I said that he looked like Napoleon Solo from the Man from U.N.C.L.E. television programme and the bubblegum cards that were a modish collector’s item among schoolgirls at that time. Charles had heard of neither. The Robertson children and I were all avidly reading Pale Fire at that point. More secret languages were being learned but I had grown too drawn by the double tongue of trying to fit in. We were preoccupied by the work and pacifism of Bertrand Russell; also by his home life.

In Charles and Robert’s bedroom, my father told me nothing but the truth, upon which he never again enlarged; very likely, for him, the only way.

‘Candia’, he said. ‘You will never see your mother again.’

People ask, ‘Are you angry with your mother?’ I am angry with neither of them though I feel vivid disgust at myself still.

I went down the inside stone stairs and out into Saxe-Coburg Place, a green square; after that, I walked around the quadrilateral autumn pavement, feeling important, shut out, and singular.

I started to tell myself the story on that day whose end is my writing this down. I shall try to tell it as exactly as I can. I thought on that day, whenever it was, that this new swerve in my story made me interesting, but I see that in fact it is a story that makes us connected, not myself singular. It is the story of loss.

That exchange, of desolation for empathy, disclosed itself to me quite close upon my mother’s death, the click of a new consciousness that I would be better advised to listen than to assert when it came to suffering, that it is not a game of trumps, and that the suffering of those one loves cannot but be worse than one’s own.

My poor father read to me all night in the basement at the Robertsons’ house, The Sword in the Stone. Can you imagine his peril and his tiredness? The sheets were linen, an act of sure hospitality on the part of our hostess. Linen sheets are chaste luxury and comfort.

Later, I became a sort of succubus upon the whole Robertson family. I was to do it with other families, too.

That night I had – or so my memory, which is as reliable as my eyelids, tells me – a dream after I fell asleep in the early morning, that foretold the future. I would go away, far away.

If this were a novel, you would learn at what chapter of The Sword in the Stone my father and I eventually fell asleep. Let’s pretend it’s when the Wart becomes a bird of prey and there come the Latin words of the Scots poet Dunbar, from his ‘Lament for the Makars’, ‘Timor Mortis Conturbat Me’.

I don’t know really. I did become rigid with fear that my skinny father would slip away too, and I took, in the coming weeks, to waking him, shaking him awake, like a first-time mother with a baby. What sort of caricature of his dead wife must I have represented at those times, reborn, younger, desperate, alive?

LENS I: Chapter 9

My mother and I were jealous of buildings, first.

My father worked for the National Monuments Record of Scotland and then for the National Trust for Scotland. He was away a good deal, and at first he went on his own. They didn’t have a car in the early years and I imagine that a baby might have been a worry, even if allowed on field trips.

If people mention the conservation of buildings now, they think at once of something almost aspirational, associated with a style of life, a type of person, a version of the past. All this could not be further from how my father thought and worked and lived. He was working to save buildings that were being blown up, set alight, anything to get rid of them and to realise the cost of the land they sat upon and to be rid of the fearful costs they and their upkeep demanded. Roofs were pulled off Scottish houses in order for the rates to be avoided. There was a cull of castles, palaces were dynamited, streets fell to the wrecking ball, squares came down in the name of progress, tenements fell in stone and dust. The war had left the sides of buildings gouged, their innards shockingly exposed, wallpaper making its sad prettiness plain, a chained mirror blitzed to wood and a shard of looking-glass.

I played on weekdays in a playground called the Wreck, down by a bomb crater near Drummond Place. Years later I realised that it was called the ‘Rec’, short for recreation. The swings at the Wreck and at Inverleith Park, where you might catch minnows in a hairnet tied to a pea-stick, were tied up on a Saturday night by the park keeper, so as not to be usable on the Sabbath. Park keepers were renowned among the children who played all day at the playgrounds, and who were worldly-wise, for being great wielders of the belt or the strap. Certainly they fiercely guarded the pavilion in the park at the end of our crescent, where I never really did dare to play, except in the rough grass. Even a fat child could get through the railings that smelt of iron, rust, coally rain and lead paint. After I got thinner I played walking along the railings on the park side. On the side of the houses, most of the railings were topped with flèches, acorns or fleurs-de-lys, except where they had been uprooted to contribute to the war effort. I felt pity in my own body for the hurt buildings, encouraged by my parents, who took me with them everywhere when they were together. Later the National Trust gave Daddy a car for work, a fat Hillman we called the Tank.

I loved to sit in the back, my head against the rattly window, watching the rain make shapes, especially in the dark and under a rug, and most especially of all, when we were going north. The humming window gave me a pitch against which I could sing, like a drone behind a bagpipe; I think the noise I made was worse than any pipe (I love the pipes violently. Until recently, I would have said that they make me hold my head up, but now my failing sight is making me do that too, so let me say that they make my blood race). My father couldn’t abide my mother’s singing, which was flat, nor mine which was flatter, and booming, and often built around long stories whose heroine was me, assisting medically at some point during Bannockburn or helping at a crisis with the Argonauts. I was very keen on Jason.

I was in love always. Odysseus seems to have been its first really intense human object. My mother heard me calling out his name in my sleep when I was six. I’d started reading the Odyssey, in the E.V. Rieu translation, under false pretences. My father said that my mother was reading it because she thought that Homer was some kind of an animal called an Odyssey. He was teasing, but patronising also. In both senses, she wanted his education. That was for sure what I think that I thought, but I don’t remember. I identified with none of Odysseus’s womenfolk, not Athene of the grey eyes, not patient Penelope, not beastly Circe, not tall Nausicaa, head and shoulders above her handmaidens in height, but preferred to confect an extra part for a brave agile young female doctor. I was very taken, when it came to the Iliad, with Achilles for his sulkiness and with Hector for his fearful sufferings; but he was never going to pull through no matter how thoroughly I bandaged him.

Comics were early stirred into the reading mix. With some tact, my father pretended to like comics too and would pay me half the price of my WHAM! in order to ‘read’ it. WHAM!, which had an excellent strip called Georgie’s Germs that had those satisfying battles between microscopic life forms that are always so rich a culture for silliness, cost threepence-halfpenny a week, pronounced, I should perhaps tell you, ‘thruppence haypenny’. Where can one begin to translate?

The source of most comics, especially in Scotland at that time, was the ultra-conservative publisher D.C. Thomson of Dundee, to whose products I was early addicted, and still am. They did not come to our house but I knew where to get them. The Dandy and the Beano I could manage without, but still must have my Broons Annual, my Oor Wullie, reassuring and harrowing in equal part. They have moved with the times. While they were stuck in the forties or so in the sixties, with a few references to Mop-Top laddies or jukeboxes, they are now shockingly less sexist and no one is picked on for being fat and or ugly.

No one was ugly in the world of the comic that addled for good my drawing style, Jackie. (‘Be bolder! Be bolder! my father would say, and once I heard my parents saying to Janey Allison’s parents at kindergarten, ‘She can’t yet get Klee.’) Jackie was thrilling pap, tame girl-friendly romance. Other girls brought it to school. I can to this day draw any Jackie type you will, daffy blonde, speccy brunette with latent romantic promise, spirited redhead, polo-necked love-bruiser, handsome toad, reliable mother’s boy. Golly, that sugar, that romantic sugar, it rotted my line. I can draw nothing like as well as either parent did, having trained myself to be more decorative than truthful in the shapes I make on the page when I draw.

But look! The blinding may be helping that, too. I’m starting to learn to draw again, teaching myself from a book given to me by my second husband. The book is called The Tao of Sketching, and it is by a Chinese artist called Qu Lei Lei, who has made an enormous portrait of our son, with a kind of predella feature, about the size of a bath, of his beautiful, strange, extra-bendy hands, folded, which is to be framed separately from the vast head.

So, there will be two ways of looking anew, with these modified eye sockets and with the help of The Tao of Sketching. I have had a good deal to unlearn, my cramped pretty curlicues, my symmetries, my velleity that tends to tidy, stretch, elide, as in fashion magazine drawing. My mother was trained in fashion drawing, and it was her work I copied at the kitchen table as we made all that fun on our own.

My father could draw, where ‘to be able to draw’ means to be able to transcribe that which you see, and pleasingly, in a way that does not betray but rather finds out, and is true to, the object seen. He could also draw decoratively from his imagination, with that trick that takes knowledge, so that he could make a line look as though it were taken from a certain architectural period, or even a period of design-influence. It is not surprising that he loved the architectural jokes of Osbert Lancaster. He had a friend, Peter Fleetwood-Hesketh, who had a similar talent. You are never quite alone with that percipience of eye, that witty strand. You can always make something of what you see. I have a few letters written by my father when he was still very young; he cannot restrain the pen. Finials grow, acroteria sprout, domes swell, columns are tactfully broken to accommodate the script; it is like wandering in a neoclassical garden, a spritzed Piranesi. He could cut paper into Corinthian capitals, into palm trees, into knights on horseback, into fretwork minarets, into a vista of a city. In one letter to a cousin he makes of a telephone receiver an Ionic capital.

My mother could make patterns, strings of cut-out dancing dolls, and she did such things with colour. It was her habit to buy second-hand clothes and to dye them in the big jam pan. Often when I got home from school, she would call out ‘I’m dyeing’ from the basement. Her colours were always changing but her favourites were silver and pink, smoky grey and mauve with no red in it. We mixed colours a lot, at the kitchen table. Guessing what the outcome would be if we mixed powder paint or watercolour or oil paint or Smarties or icing or ribbons, this was a good game. She let me paint potato crisps and offer them around when her friends came to drink coffee or – at Christmas, I think – Cinzano Bianco. She scribbled with wax crayons on cartridge paper – very expensive – and let me colour in all the little moons between the waxen boundaries of scribble, and to try never to have a colour adjacent to itself; was that possible? We used her paints from her student days, a Rowney set with little replaceable pans of watercolour, and a Cotman set whose replacements came wrapped in paper like sweets from Aitken Dott the art supplies shop on Hanover Street.

I had some triangular wooden mosaics with which I made patterns, and some wooden sticks named Cuisenaire that my poor parents hoped would make me better at mathematics, and architectural wooden blocks from Germany in a duffel bag. I would ask my mother all the time, ‘Which do you like best?’, ‘Which is your favourite?’ She would make a case for each. I do it with my children. The youngest gets cross. He thinks that I am being politically correct, that I am in thrall to the tediously New Labourite phenomenon he calls ‘the Equal Elves’. I’m afraid I am just copying my mother.

I cannot remember much about my mother, but I shall try, now, to do it. I am looking for her and with her for my ability to look.

I have looked away from it for a long time while pretending to look at it. God knows how it is for people who contemplate the disintegration or physical fission of someone they love. At least she was in one piece in my bed where she, at thirty-six, lay dead.

I regard (a word of seeing, I see) that last sentence as too aggressive to the reader, too showy, to remain. It is bad form. I cannot, I observe, look at it. So I’m going to make an experiment, and leave it.

I will now try to remake my mother’s last day during which she took me to the Nubian goat farm at Cammo to choose a pointer puppy, a dog that must have been a sop to me, or perhaps to herself, like the drugged meat burglars are said to throw for guard dogs. I remember the lop-eared goats and the brindle pups.

When with either of my parents, I had the sense that each was fragile. I asked them that disturbing incessant question, ‘Are you all right?’ a lot. His breathing sounded wrong, they fought too much, she cried on the edge of her bed. I avoided them on account of this, and hung about after school with the boarders, or walked home with other girls, bribing them with the bus fare I would save by walking. I had friends by now, other children of bookish homes, or daughters of my parents’ friends. I wasn’t popular, but I was on the verge of being a cult. Something was happening at home and other girls’ parents talked about it.

By no means all fathers liked finding me at the after-school tea table when they got in from work. There was something provisional and not respectable about me. It wasn’t just that my mother was tall and sexy and wore sometimes a silver and sometimes a pink wig, that she smoked or had that Englishy voice, the Siamese on a lead, the black poodle-cross (named Agip after Italian petrol—‘supercorte maggiore, la potenta benzina Italiana’) or the yellow Labrador Katie. It wasn’t really anything as simple as that I was not named Fiona or Elspeth. I was a Mc, after all, if not a Mac. It wasn’t as though she didn’t hand out jars of home-made, misspelt ‘blackcurrent’ jam, that delicious staining preserve with something of its leaves’ cat’s-pee tang to the black fruit.

It wasn’t Mummy’s awful driving. She learned only late in her life and had a half-timbered Mini van that got into scrapes. She might put the card discs from tubes of Horlicks tablets in the parking meters in Charlotte Square instead of sixpence.

That’s the worst thing, morally, I saw her do.

She was pursued by more than one man who was not within her marriage. One of these, later, after I was the mother of three, came round for lunch with me in my marital home.

‘What happened to your mother?’ he asked.

‘She died,’ I said.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘What are you doing this afternoon?’

As I’ve said, a number of people have wanted to tell me what my mother did in her last days, or on her last day. I have no desire to know. I may be wrong in this. Other people are involved, and I don’t want them hurt. I don’t want anecdotes or gossip. I want the emotional truth, so I can make her better. And that I cannot have. I want the printout of her human heart.

I do not think that we can at this distance know the truth.

I do not think that we could even then have known the truth or seen it.

I have very often wanted to take from her thoughts whatever it was that so hurt her that she felt she had to die, and to replace it with the complete certainty that she is loved, and that by people, my children, their fathers, who never even knew her. I do not know how I know this save that she has grown less fragile, less contingent and less fantastic in my mind, the longer she has been dead. In life she felt frail to me, like a story, unless stories are not frail.