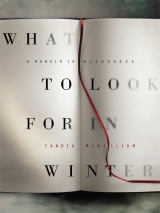

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Bridge

My house in Oxford lay, and still lies, last in a Regency cul-de-sac of artisans’ houses behind an almost Georgian street that is at right angles to the comely parade of Beaumont Street that itself holds both the Ashmolean Museum and the Randolph Hotel.

I finished writing the last chapter you read on Ash Wednesday 2007. I am now speaking to you.

Deeper into the year on a hot May day, I very nearly burned my house to ash. Being an old terraced house made of wood and lath, it might as well have been a blue touchpaper.

As had become usual, I couldn’t see that day. I had become used to groping my way up and down the narrow staircase of the house, much as you do on a boat. For reasons to be seen, I have spent a good deal of my life in boats. Nonetheless, I am no good in on at or with them. I had acclimatised myself to the layout of the house but still banged into things and fell over frequently, especially over the piles of books. The things I loved had, though I didn’t know it, become a danger to me, and twice I slid gratingly face first down a flight of stairs over a slither of hardbacks, old TLSs and magazines. I was used to having bloody knees like a schoolboy and bruised hips like a mother with a granite baby. That hot day I was as usual pretending to myself and to the nobody at all who was looking that everything was all right.

I had run dry on doctors. My condition’s intractability either exasperated or baffled them and such significant words as ‘referral’ and ‘Queen Square’ had been muttered. One psychiatrist who vividly reminded me of the Scottish wizard Michael Scott who is mentioned in the Purgatorio, said that I had chosen to close my eyes against the unbearable sight of Fram’s happiness with his new love Claudia; I came back with the old argument – that since I love him I wish him to be happy. There was an air of psychological manipulation in that expensive room that might be better kept for playwrights than appointed healers.

There was the episode of the wonderfully named Alexina Fantato, who turned out to be not a strapping Italian glamourpuss with sexy but stern spectacles but a dear lady from Scotland married to an Italian. There’s a tradition in Scotland for these feminine-ending masculine names, Donalda, Kennethina. It seems that all note of disappointment is unintentional, unlike those long declensions of heir-hungry hermaphroditic names to be found in Burke. Alexina shrewdly saw that I had ‘issues’, as she kindly expressed it, with self-esteem. I made my usual noises about preferring to live by suppression than by spillage. She made a sensibly pawky face of disbelief at how someone this old could so mismanage her life.

When Proust comes to his account of the death of Marcel’s grandmother, the old lady and her grandson pay a visit to a distinguished doctor whom the narrator will not even dignify with an invented name. Simply referring to the smug physician with his failure in humane understanding, the prerequisite of good doctoring, as Professor E—, Proust has the man manifest his heartlessness and hypocrisy under cover of a decorous but fishy anonymity. My own Professor E – washed his hands of me in sight of a witness, Claudia, whose sharp large blue gaze saw and recorded it all. She is more direct than I could ever even try to be. Professor E—, intelligent, disinfected, effective, spoke:

‘I have done all I can for you. Some people may suggest that there is a non-physiological aspect to this unhappy condition of yours, which is always a distressing one. They are wasting their time and they would be wasting yours. You will not find it profitable to go down that route.’

I am still cleaving my way down that route, although the route itself has sometimes seemed to be narrowing, the stream drying up to reveal only little pebbles, hard stones hardly wet at all even by the grace of artificial tears, and this book is part of the walk following that diminishing way to some kind of resolution, if not the open lens of sight itself. Of course it is physiological; of course the cause of my blindness is neurological. But who says the life lived is separate from the body that has lived it?

Back to that stuffy day in May, my cats and I shut in the small wooden house. I was in my workroom and felt my eyes’ heat and discomfort become sharper. I pulled them open, unsticking my eyelashes. Even peeled, my eyes saw nothing. But this nothing was not black or stippled or veiled or any shade of the blindings I had grown used to; it was thick white.

That is how slow I was to realise that my small house was full of smoke. I did not think at all, which must have saved my life. Usually I am a great one for telling myself not to make a fuss and certainly not to bother other people, especially not the already overloaded public sector. I banged my way to the telephone, rang 999 and got a woman in Glasgow.

For the first occasion in my life, and not the last, I used my newly acquired unfair advantage, and I expressed it in words that felt like rhubarb in my teeth. ‘My house is on fire. I’m partially sighted.’ The woman with the reassuring Scots voice asked where I was and I replied to her as if we were sharing a sofa and a biscuit, ‘I’m in Beaumont Buildings. It’s a street in Oxford. It’s not a building.’

On I prattled in my burning house.

‘We’ll be with you right away, dear. Hold on and get out of the house right away, closing all doors you can behind you.’

‘But I’ve two cats.’

‘You’ll have to leave them.’

Now I see how patient she was with me, with all the flaming nation clamouring for her attention.

I didn’t obey and I did try hopelessly in the, I was now aware, reeking house to find my cats. I chased them, for some reason I can’t understand, into the basement and shut them in, or so I thought, but my thinking was as fogged as a choking drunk’s, and I was left to reflex alone and to action, perhaps my two weakest behavioural suits.

All that in a whisker. I was soon in the street with three fire engines and a score of strong young competent people. Yes, a firewoman too, and all of them concentrated on reducing harm and bringing later calm.

A neighbour took me in. A fireperson like the young Hector stayed with me and asked my neighbour to make tea. He actually asked me whether or not I took sugar. We conversed. Again it was the sofa and biscuit feeling. I learned that he was a keen hunt-follower, and that he and his wife couldn’t afford to buy a house in the Oxford area so that he had a long commute to his extraordinary work.

‘In fact,’ he said, ‘we’re really grateful to you because we had a city councillor visiting the station with a view to cutting down the service. Then you came through. You won’t mind my saying that it’s extra good you’re blind.’ How could I not love him?

Two hours later, everything but my oven was spick and span. Having seen smoke damage and water damage and having lost one house to arson, I was astonished. It was just like magic. The ‘emergency services’ had been heroic, the staled newsreader’s words had immediate Homeric meaning. These stern-faced young people had entered the house, located the source of the smoke, hacked the oven out of the wall, taken it outside, extinguished what turned out to be spontaneous chemical smouldering, sucked all the smoke out of the house, swept the kitchen, wiped the surfaces, and all but put a nosegay on the draining board. They had also attended to any over-spilling olfactory offensiveness that might have been caused to my next-door neighbour who had of course been regrettably interrupted by the bells and smells of the fire engines.

I asked them all when they stood round me, helmets off, after it, what I could do for them.

‘Write a letter to head office, that would be great. If you think we did our job properly.’

I wrote several such letters in my best writing that looks like my old worst writing. These were love letters.

And the cats? Of course, an officer had been deputed to find and liaise with them, so much so that his uniform may never recover from the cuddling.

That night, without my knowing it, my translation was organised. My second husband telephoned to my first husband and got my older son. It turned out that the fire, which could have been so much worse, came like a catastrophe in a play, a kind of relief, so that at last my family could talk about my blindness and where to put it and me and my two cats.

The novels of Iris Murdoch are, for the time being, out of fashion. She has become someone in a film, someone pitiable even, someone who has been impersonated by souls who haven’t read her work. It is not my place nor intention here to play reputations but in her time she was an enchantress and her philosophical work contains much that is luminous; as a girl, she presciently noted Simone Weil’s words suggesting that deracinated people can be among those who cause the most damage.

I mention Iris, whom it’s only fair to say I did slightly know (in case someone wants to niggle about Oxford’s closed hive), because what happened to the cats could only have been invented or written, in its full richness, by her. My cats, for the duration of my move from Oxford to London and the first precarious London weeks, were cared for by a couple named Leander and Rachel.

Leander and Rachel, at the insistence of each of their mothers, had moved from their flat in Stockwell with their own at the time five cats to Oxford where Leander lectures at Brookes University. The couple first met in the Lemon Tree cafeteria on Platform 8 at Reading Station. There was a theory to this, the Ancient Greek theory of buying off expectation, like calling the Fates the ‘Kindly Ones’.

If you meet, the theory of Leander and Rachel ran, in a truly awful place, your relationship will prosper and your love be lifelong. When they first met, my younger son was seven. He started angling to be pageboy at their wedding when he was about seven and a quarter.

He was finally the ring-bearer at their ceremony of civil partnership on a summer afternoon in 2007. Leander, a stunning redhead, as the old social magazines might have said, wore a frock modelled on that of Mrs John F. Kennedy, designed by Oleg Cassini, at the Presidential Inauguration Ball. Rachel, a beautiful petite brunette, wore an ivory silk sheath.

Leander, which is her real name, arrived in our lives with as much competence and fabulousness as Mary Poppins. She came with an emerald dolphin nose-stud and streaming red hair, to be my daily lady. She has stayed at the core of our lives as good genius, role model, Christian example (of course she’s an ex-Goth), Green activist, mentor, cat counsellor, nearest thing to a nanny in every good way and none of the bad, sci-fi nut, baker of weekly cakes and friend of the heart, together with her lovely wife, archaeologist, academic, beauty and the driest wit this side of Campari. Lists like this can be lazy, but there is a crammed goodness to the pair that has almost literally sustained me during the locust years.

At the reception there were fifteen wedding cakes including one topped with a bride and bride, and, for the duration of that hot green garden afternoon with children playing in several languages around us, I sat under a tree with my son and Leander’s mum and dad and allowed a new thought to cross my mind: that all could be well.

It was late June of that same year. My older son Oliver and I met in, as the nonsensical phrase has it, a ‘residential’ part of London where, even with my photophobia and flinching face, I perceived that I would feel like a thistle in a plushy meadow if I pretended to live hereabouts. My son had taken time off work. He is half a foot taller than I am. I love to be in his shadow. He was in a suit. The day was unbreathably hot. I could see he was missing important phone calls.

We were nearing the end of our list of flats for rent. We had squeezed our frames into several highly accoutred provisional and meretricious spaces with nice keen girls. We had viewed eight leather sofas and three very thin tellies. How did I see this? By doing as I’m doing now, to read this through, by pulling up my eyelids’ raw skin, and by making mad faces.

I feel like Mrs Tiggy-winkle with the spikes growing inwards especially over my eyes. I move like Mrs Tiggy-winkle too, tentatively shuffling as though in slippers and very old. I climb upstairs like a child of two.

We had one flat left. We had heard about it only that morning. Over breakfast, Olly’s godfather had told Fram, who is his great friend, that he had just inherited somewhere off the King’s Road, its owner an American artist who had lived for many years in Italy before moving to London in the nineteen-seventies. He painted right up till almost the very end and the last two squiggles of pigment he chose are still sitting on his palette under an inverted toffee tin. Mauve and ochre, the colours of shadow in Rome.

We sat in Olly’s car. I could feel his thin skin not liking the heat of the day. He has hair the colour of the flame on a firelighter packet and slanting green eyes. I was melting like an old cake. We were only just not tearful, like hot children on a birthday.

We shook ourselves down, he clicked shut his car and we ambled to a house that I had not entered since having dinner there thirty years before in the company of my father’s old schoolfriend Simon Raven.

The street was a chasm of heatwave. We pressed one of four bells. Two heavy doors were opened and we stepped into what might as well, that afternoon, have been in its shaded refreshing dinginess, a segment of a palace in Venice.

Oliver, who is formal in his manner and composed of jokes and understatement, said, ‘It’s like your old life, Mummy. Look at all the books.’

I could smell home. Books, linoleum, dust, polish, oil paint, soot, laurel and the very faint note of drains. Edinburgh, Cortona, Karachi, the Hebrides. And now Tite Street.

LENS II: Chapter 1

If I’d stayed at home, would it all have happened? Or is this every runaway’s question when chased down by shame?

It’s certainly a question you might have wanted to ask of my uncle Clement, who, if he’d been able to stay at home at ‘Dunkeld’, my paternal grandparents’ home in Sydenham, or at his and my grandmother’s grace-and-favour house at Windsor Castle, where he was organist and choirmaster at St George’s Chapel, might not have married or become a father. Would his musicality, sheltered, have made him a more sung English composer of the twentieth century? Or would he have chosen, as he did, his own merry means of death as one of the seven Noble Gentlemen of Poverty at St Cross in Winchester? Fewer than a dozen of us went to his funeral at Basingstoke Crem.

Clement’s son, David, one of my only two first cousins, who looks lugubrious and is funny, very handsome in the darker Italian fashion, stepped forward and stuck on Clement’s coffin as it slipped through the curtains the label he had steamed off his daddy’s last bottle of Gordon’s Gin. ‘Mrs Gordon’, Clement called it. For him, not mother’s ruin at all, but quite possibly a mother’s boy’s compensation for that mother’s absence.

Winchester Cathedral rang with voice at his memorial. He paid for his gin by giving maths tuition to the children of takeaway proprietors and late-night shopkeepers, ambitious for their children’s rise up the slippery pole Clement had negotiated by ignoring or perhaps remaining innocent of it. He saw the sad and funny, not the worldly, in the world.

McWilliams do this thing of fading out. They die young and they stay in touch with the aid of telepathy, of not writing letters and certainly not making telephone calls. They tend to eat unhealthily, to be musical and scholarly to the point of dust in their habits, with strong genes for self-effacement, religious faith (C of E in the rest of the world and Episcopalian in Scotland, or converts to Roman Catholicism), medicine and spying. They have been explorers and teachers but mostly they have been naval surgeons, musicians and secret poets. Their habits are gentle and they have a sweet tooth. Almost sickly thin in youth, they may get tubby later. It could in only some few cases be something to do with drink. It is not hard to see why they were only briefly kings of Scotland. My daughter Clementine compares them favourably with that reproductively inefficient animal, the panda. ‘McWilliams are rubbish at dating,’ she says, ‘but pandas are really rubbish at it.’

Clement himself loved the detective stories of Edmund Crispin, King Penguins, of which he had collected almost the entire run, the music of Buxtehude, Wilkie Collins. He knew his Bradshaw intimately, which of course gave him heartbreak as the railways were privatised. He slept from time to time on park benches. He wrote operas for children, preferred tinned fruit, and hummed as though continually about to hatch.

My father was not a drinker. He was a Capstan Full Strength Navy Cut untipped man. He gave up after his stroke, simply smoked seventeen in a row in the hospital and never again. Not that there was long to go. His stroke had hit him while he was walking along reading a Posy Simmonds book in Charlotte Square. Perhaps it was an excess of pleasure that felled him.

Up ahead of Clement and me is my robust Cousin Audrey. A dead ringer for Christine Keeler, Cousin Audrey is a Champagne girl, and I hope she won’t mind if I say that she is now to the north of seventy, in her cloud of fragrance purchased at Jenners, the Queen of Edinburgh department stores, and surrounded by the ghosts of terriers and horses. Cousin Audrey is my mother’s first cousin and is a Young of Young’s Malt Loaf, delicious, healthful and profitable. Young’s Malt Loaf will be remembered by some for its acronym: YOUMA, long since, to Cousin Audrey’s righteous and splendid ire, munched up by United Biscuits, now a mere crumb in Nabisco, which may be just a corner of Nestlé. Cousin Audrey keeps tabs on us all; she is not a McWilliam. McWilliams are mainly socialists and Cousin Audrey, to whom I can’t not, as you will have seen, give her full title, does, energetically, use the telephone. She has graced stages from Pitlochry to London. One of her dearest friends, a Miss Balfour-Melville, she addresses as Miss Balfour-Melville. Miss Rosalind Balfour-Melville will this week be one hundred years old; we are in May 2008. For her birthday present she has requested a new white frock with a lot of wear in it. That’s Old Edinburgh for you.

When Cousin Audrey is puffed out, she declares, ‘Whew! I’m peched.’ When she’s feeling dotty, she says, ‘I know you think I’m up the lum.’ Cousin Audrey is an alumna of a now-defunct Edinburgh school called St Trinnean’s, which is, you understand, not remotely the same as being a girl from St Margaret’s, which is quite distinct from Lansdowne House, George Watson’s Ladies’ College, Heriot’s or St George’s, which as it happens is where I went. St George’s is to the naked eye intensely Scots but to the understanding of mockers of a tubby wearer of its uniform in the nineteen-sixties, almost up-itself English.

My plaits often got filled with chewing gum on the bus or tied to the seat handles. The girls did the gum, the boys the tethering. Maybe it was the scarlet cockade on my beret embroidered with St George piercing his curly dragon and those four nouns from ‘The Knight’s Tale’, TRUTH, HONOUR, FREEDOM and COURTESY. In summer, we wore white gloves with our lightweight, fine puppystooth check, A-line coats; in winter the older girls sported a suit, known as a ‘costume’ and a cardigan in a shade named Ancient Red. I was only a ‘big girl’ for a year, but during that year was privileged to enter the mysteries of the Senior-style undergarments: white knickers, navy knickers, white cotton suspender belt and stockings, in the shade Aristoc ‘Allure’, the colour of strong tea with evaporated milk. There was a racier option, American Tan, that was a shiny auburn, the tea without the milk. The uniform came from Aitken & Niven or Forsyth’s; it goes without saying that there were distinctions between the two shops. Forsyth’s had a slightly swingier clientele and had perhaps less Old Edinburgh tone; it sold sportswear (tennis, croquet, skiing, cricket) and you sat on a polar bear to get your shoes fitted.

One of the things people ask, if they notice that you are female and gather that you might have been schooled in Edinburgh, is ‘Were you at one of those Jean Brodie style schools?’ There is of course no such thing; how Miss Brodie would have abhorred this sloppy generalising. But there’s no denying the precision of the echoes for St George’s. We were superbly taught by fine Scotswomen, mostly unwed, who had been unmanned by war. We started Latin and Greek before these languages could alarm us, while we were yet in our baby-pinafores.

My parents could not afford the fees. I got some kind of scholarship. My mother’s parents paid the rest, and I think minded. My parents fought about it. My father was vehemently agin private education. (I believe he married two women who may at least once in their lives have voted Conservative.) My maternal grandfather was self-made and highly suspicious of education beyond the respectable zones of business, boxing and golf. He read the FT and the Reading Gazette. He was quite right about the power of learning for its own sake, its huge and blessed leverage for freedom, the vital key it hands you should you require to escape.

Cousin Audrey’s hot on business too and to this very day often berates me, quite correctly and very loudly, for my pointlessness and the pointlessness of what I laughably do for a living. Nonetheless, she has in her time loyally attended readings given by me and at least one gentleman known in the wider world to be ‘that way’. She’s a bonny heckler and one of the bravest souls you will ever meet, a glamorous spinster of the old school, shrewd, courageous, greatly loved and on her own. She reads the right-wing press with close attention. It broke my heart when I suggested the Guardian or the Independent and she took up both. I feared for her imbalance. Her favourite paper is now officially the Independent, her favourite man in the world Boris Johnson, with two little pouches for my sons Oliver and Minoo. She is a man’s woman and has the hairdo to prove it, confected weekly by her dear friend Muriel Brattisani, of the famous Brattisani family, whose lobster and chips and cairry-oot Champagne are the talk of the entire globe.

My German publisher wrote to me once describing Oxford as ‘the Omphalos of the known world’. He went on to become Minister of the Arts for Germany and then, with some relief, the editor of Die Zeit.

Anyhow, Edinburgh knows that it is the centre of the known world and wheesht to your omphaloi. Has a doughnut an omphalos? We’re talking baked goods here. Omphalos? Can you export it? Well, of course you can, and we are an emigrated race, the Scots, bringing our notion of civilisation wherever we go, bridges, sugary snacks, books and stories, fighting and drinking.

What I’m trying to get round to is my birthday, the 1st of July 1955, the birthday of Julius Caesar, for whom my third name is Juliet. In October I was christened at Rosslyn Chapel, burial place of the Earls of Orkney, scene of The Lay of the Last Minstrel by Sir Walter Scott, reputed resting place of, among other things, the Holy Grail and the True Cross and scored with a number of unexplained Masonic symbols. I wrote in a novel twenty years ago about this numinous jewel in stone. Of course, its anonymity has since been rather blown by Dan Brown. It contains among countless other solid beauties, the ‘Apprentice Pillar’, a piece of carving so virtuosic that the chief mason is said to have murdered its maker, a mere apprentice, for his presumption, and then hanged himself in remorse. There is a small carving of the grieving master mason, his mouth an appalled hole. This pillar is depicted on the front of one of my father’s volumes in ‘The Buildings of Scotland’ series. Daddy died in the middle of writing Dumfries and Galloway. On the front of that volume is one of the Duke of Buccleuch’s palaces, Drumlanrig House, out of which, not very long ago, someone walked unnoticed carrying a small painting by Leonardo.

That’s carry-out for you on a scale beyond even lobster. The painting has since been returned. The late Duke was once our Member of Parliament and I remember him canvassing in Thistle Street, a tall curly-headed long man, before he broke his back out hunting. His father, the old Duke, had a silver wine cooler the size of a cow trough into which I remember being put for fun as a small child. Like being in a huge deep ladle of precious reflective metal, it fitted me fine. All made to hold drink.

My lips had never touched liquor then.

I was an only child, but even then somehow stood aside from properly inhabiting a self, even though at the beginning it was a fairly chunky self to inhabit. I played with dolls, glass animals, and small unmatching china tea services that my mother collected in junk shops. Wherever she went, I was. I followed her stuck like a limpet to its home-scar. I loved the scent of her forearms and the smell of her hands that combined acetone, coffee, Atrixo hand cream and cooked garlic.

In our crescent lived many mothers of families to whom Mummy became close. Constance Kuenssberg was a doctor and the wife of Ekke, our doctor, who came out day and night for us.

Ekke’s father had written to him when Ekke was a boy at Salem in Germany, the school set up by Kurt Hahn who later founded Gordonstoun. It was 1935 and the Nuremberg Laws had just been passed. In Ekke’s father’s letter were the instructions to walk out of Germany into neutral Switzerland, down into France, and thence to Great Britain. Ekke did this. He was interned as an enemy alien on the Isle of Man, which some have described as being a kind of university then, a virtuous Babel. On his arrival in Edinburgh, Ekke trained to become a general practitioner and married Constance, who was part of the Edinburgh establishment, being daughter of the Rector of Edinburgh Academy. This extraordinary couple did much to set up the National Health Service in Scotland. Ekke’s son is now still my stepmother’s doctor.

For a more expansively raised generation I should say that you had, at that time (if you had shoes at all), indoor shoes and outdoor shoes, the line between each being the front door of any dwelling place. The purpose of these designations was cleanliness. It did not do to bring the outdoors in. You might spoil someone’s good housekeeping. It was a matter of everything in its proper place.

The cold: each day was a fight to keep the cold outside where it belonged and not let it into the house, though houses were freezing inside too; there was an unsleeping vigilance against cold as it came in from the sea and down from the hills and off from the mountains and into our bones. If the air was not misty with human breath and surreptitious attempts at thaw, it was misty with the haar, the mist off the sea, of which some Edinburgh residents were in my childhood very proud as it was yet another way of keeping yourself to yourself.

It was not unusual to see people ski the winter streets. Mothers would pull children on toboggans to fetch the messages, which is Edinburgh for ‘do the shopping’. Old ladies walked as I do now that I’m blind in the snowless streets of London, side-shuffling along the pavement while nervous hands feel for the next railing. I cracked today into a column of sixties brick, the corner of what used to be a rather ritzy rehabilitation clinic. The bruise is coming up nicely. Today’s blepharospasm doctor wryly remarked, ‘The clinic got out six months ago, or you might have been able to sue. It belongs to a property developer now and they’re a bit more hard-headed.’

My mother’s and my favourite junk shop was Mrs Virtue’s, in a basement on a corner with her name up in subtly shaded sign-writing emphasised in gold. The steps down to Mrs V’s had iron handrails curled to right and left. She herself wore a hairnet, a navy angora hat, a musquash coat, a pink-flowered pinny, many cardigans topped by a maroon one, a Clydella vest, fingerless gloves, varicose veins, stockings and socks, and what were called indoor shoes.

Mrs Virtue’s shop was a tunnel of mattresses twenty deep on either side, damp with cats’ piss. It was hard to imagine Mrs Virtue outside her musty nest. It is likely that she and her cats had a shared diet, though she smoked more than they did. I can’t think why I never stole anything from Mrs Virtue’s shop. Can it have been original virtue in me? The place was so chaotic and I so young that I understood the set-up as how things were meant to be and would not have dared spoil the careful arrangements Mrs Virtue appeared to have made. She had a face like chiffon for wrinkling and intermittent sets of teeth. Her eyes were dark and missed little.

Mummy spent hours talking to Mrs Virtue. They had far more than cats in common. I didn’t know then that these long conversations with people outside her marriage were a symptom of her loneliness as well as of her curiosity and friendliness. I am certain she was not signalling this loneliness to anyone intentionally, leave alone to me. She wanted to be the best of mothers.

It is not easy to say this out loud and before I went blind I would not have had to, but this greedy obsessive recall of trivial (and, it’s not lost on me, mainly visual) detail has clamped to me even closer as a habit since I lost my capacity to see. I was made of what I saw. I saw in panorama and in focus. I saw things at and even over the edge. I wasn’t half so good at hearing.

I’m scared I’ve become like an inventory for the sale of an old dead person’s house, what Scots call a displenishing; here I am, picking up lost bits and pieces of my scattered life to try to make something whole by putting it all together, my own flotsam and jetsam.