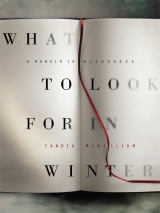

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

In time for this largeness, the couple’s first baby was born, at home, my half-brother Nicholas Charles, named for Nikolaus Pevsner. We had become a churchgoing family, attending the highest of high churches in Edinburgh, Old St Paul’s. Some Sundays Father Chancellor, with or without his curate Father Holloway, would come for Sunday lunch. I loved Father Chancellor with his beard, big voice and golden robes. He was later said to have taken to drink. Father Holloway became Bishop of Edinburgh, then the chief Episcopalian bishop in Scotland, then lost his faith and is now a prolific writer and opinion-former. He gave the address at my father’s funeral though, quite possibly by arrangement with God, I never got to hear it, as will become clear.

The density of the frankincense, dispersed during the very long Sunday services by the swinging ball of the thurifer, was difficult for my poor stepmother during her two pregnancies and she sometimes felt faint. I developed a taste I have never lost for the ritual and intoning and chanting and bobbing and bowing of the High Church and indeed it is very confused with my faith, which is, as I write, giving me some trouble.

My first conscious taste of alcohol was after a church service. I am unconfirmed and have therefore never tasted Communion wine, and, even should I become confirmed, I shan’t taste it (confirmed alcoholics avoid the wine and take only the Host). This liquor was in an eggy Dutch drink named advocaat, to be eaten off a spoon, so guileless was the substance that was to reduce me as low as you can get this side of whoring and the grave. As many drinkers boringly say, I didn’t like the taste of the drink. I loved the Roka cheese biscuits that looked like the wattle fences on my toy farm in the blue and yellow tin that had in Dutch the slogan ‘De andere half van uw borrel’ (the other half of your cocktail).

My half-sister Anna-Sophia came next. Both my half-siblings are a charming combination of their parents and I can never believe or understand why they are so nice to me. I like them a lot and we stay in touch in the usual way; by not getting in touch. Nicholas, who has cycled across the Ukraine, made maps in Afghanistan and is on speaking terms with the North and the South Pole, is perhaps the most outstandingly silent of us though he will suddenly send a book of Tanzanian recipes or a picture postcard from Thule. Anna and I have been known to share a meal. We share the same jokes but we don’t need to talk about it. I think we loved our father from something of a similar angle.

After my father’s death, I was stopped in the street in Oxford by a handsome young man who asked me the way to somewhere. I started to describe it in the usual manner, giving helpful details but not very long on such things as north and south.

‘Do you mind my asking this,’ said the young man, ‘but are you related to the McWilliams?’

It turned out that he was the doctor who had had to break the news of my father’s sudden death at work to my stepmother. It was the precision and uselessness of my directions that gave him the instinct that told him who I was.

I often try to imagine how it must have been for my stepmother faced with me. All I wanted to do was read, and reading doesn’t shake off the fat. To her credit, she got me out on to the street. I skipped and skipped and skipped and skipped and skipped. There were plenty of rhymes that went with the skipping:

‘Edinburgh, Leith,

Portobello, Musselburgh–

AND Dalkeith.’

And:

‘Andy-Spandy

Sugardy-Candy,

French Almond Rock

Bread and butter for your supper’s all your mother’s got!’

I skipped a minimum of one thousand whirls of the rope a day. My record at backward skipping was 305, and, fortunately enough, I forget the record for forward skipping. People did play more in the streets in those days, it’s true, and not just something said to make today’s young feel bad. We played hopscotch, we stilt-walked, and my stepmother even taught me to ride a bicycle. It is unimaginable to a person of Dutch extraction that any human being cannot ride a bicycle.

Dreadfully, because I felt and expressed no gratitude, only fear, I became the owner of an expensive new bicycle and soon I was cycling to school and guiltily getting off and pushing the bicycle and walking whenever I could. This bicycle, a generous gift from my stepmother, remained in my life all through Cambridge, when I used it once, and right up till the time when I worked at Vogue. Its last ever ride was between Warwick Avenue and Vogue House. Even in the nineteen-seventies, Hyde Park Corner was challenging to a wholly uncoordinated cyclist, attired as a matter of course as a flower fairy in buttoned boots and skeletal on a diet of vanity and fear.

I started to dread going home after school because I knew that I would in my absence have fallen short. Something quite evidently needed to be done with me, aged nine, and my stepmother rose honourably to the challenge. I could not have gone on as I had under my mother’s sway, just reading and drawing and emoting and inventing worlds, completely certain of at least one person’s love, dawdling in affection’s shade.

My stepmother did a good job. I did get thinner and I am quite a good housewife, though I do not have her gift for making of any space a dustless geometric zone of purity. I am like my mother and like my daughter, a collector of clutter, but I have a nice healthy case of obsessive-compulsive disorder and replicate many of the routines that I learned at my stepmother’s hand.

The really bad thing was the lying, and that was of course, of my own invention; QED. It hurts to lie, damages the understanding of the self and bruises any love that might be about. I seldom lied to give myself importance. I’m not interested in boasting. I’m afraid I lied in order to find some peace, which of course I did not, and in order to find love, which I then found on terms that were not healthy, or, rather, it was not love that I found, whenever I thought I had.

I just wanted to be left alone to read. I did not seem to be able to become the kind of child that was familiar to Christine, that she and her siblings had been, that Nicola, so close to me in age, evidently was.

My father and his new family were relieved of me during the holidays by the inspired intervention of my step-grandmother Mama, who would have me to stay either in Herefordshire or, in the summer months, at the progress of Jannink family houses across Holland.

It is said that Scottish writing cannot be separated from the idea of doubleness, and I feel it to be so as I speak private things aloud to Liv. I hear the echoes as I confess in my unbelonging-anywhere voice in this tall cold English room.

The first time I tasted milk fresh from the cow was at Christine’s parents’ farm. They had Jersey cows. Mama brought me a mug of milk in bed. She took it for granted that she would listen to my prayers. No one had asked this of me, or given this chance to me, before. I was enchanted. When she told me off I could at once see her point of view. It must have been upsetting for her to see her own daughter struggling with the ugly child whom she herself could handle with ease.

I took a sip of the milk after I’d said my prayers to Mama. It was absolutely disgusting, so rich, so sappy. Like little Gillian at my unsuccessful birthday tea, hating the real cream, I longed for town milk, milk, at any rate, that did not proclaim so gutsily its proven ance from a cow.

Mama and her husband, whom I called Papa with a long last ‘a’, were from different parts of Holland, she from Amsterdam and he from a large estate near Enschede, close to the German border. She had been an actress and had the poignant features all her long life of a sort of bespectacled Ava Gardner. He was tall, blond, handsome, beautifully dressed, very quiet and subdued, by the time I knew him at all well, by Parkinson’s disease. This meant that Mama had to undertake not only the feminine side of English country life but, increasingly, the running of the farm and the decision-taking, all of it. Her care of her husband disguised itself as nagging. In fact she was keeping him alive by making him stay as fit as he could by not giving in and letting her do everything. She forced him to feed himself, to do his buttons, to walk tall. Yet again she was evidencing imaginative, maternal, love, in this case to her unmanned and, possibly, previously dominant husband.

Every summer until I ran away Mama drove Papa, Nicola and me to one of the seaports for the Hook of Holland or for Rotterdam. She managed everything, from teaching me how to pack a suitcase, to the passports, the seasickness and carsickness, my heavy resistance to Nicola, Nicola’s distaste for me, the maps, the driving, the shopping, the cooking. She even got me to play cards.

I had long been afraid of card games. At some point in my life before Christine, I had met playing cards; I put about the untruth that my religion forbade me to play with them. I was simply bored by them and very likely too innumerate and idle to take an interest.

The first part of our Dutch summers was always spent at the Jannink seaside holiday house, Duinroosje, which means Little Dune-rose. The dune rose is what we know as Rosa rugosa, whose tomatoey hips make excellent jelly and whose pips make good itching powder. Papa was one of seven children and there were many pretty little blonde cousins. Naturally Nicola spoke Dutch to her cousins. Naturally, too, my Dutch took a while to get off the ground. There was the additional problem of my height. Nowadays Dutch people are often tall but it did not seem to be the case then and once or twice there was real trouble when I was queuing, after our early morning swim in the sea, for our daily buns or kadetjes, because people thought I was German. On our kadetjes we had little seeds of anise in sugar, called muisjes, that is, little mice. They were pink and white and blue. When an heir to the House of Orange was born, Mama said, all the muisjes in Holland were orange. There was chocolate hail for breakfast too, chocolade hagelslaag. The softness of the Dutch language is delightful and my step-grandparents’ English was winningly softened by their Dutch accents, so they said ‘of’ for ‘or’ and ‘v’ for ‘w’. It is a language I have long ceased to resent, though for some summers I felt it shut me out, till I got the ear for it. Italy had come more easily to me, but Holland is quite deep in me by now.

Mama managed the business of feeding me while controlling my fatness with the kind of commonsensical grace she brought to every aspect of managing me. Dutch food is delicious and highly calorific, featuring much bread and butter, plenty of red meat, pancakes the size of sunhats, snacks between meals, these snacks baffled under drifts of icing sugar or slathered with mayonnaise and washed down with bottles of stuff the milkman delivered called Chocomel, which is just chocolate milk. Mama wilily discovered that what I like best in the way of food is herrings and fresh fruit and that I loved to swim in the sea; and so she too helped reduce in dimension this seal-like child that had been washed up on her family’s shore.

It was at Duinroosje, where we lay having a rest, as we had to every afternoon, in the yellow-painted metal-tubing bunks, that Nicola told me that she came from a different, more elevated, social class than I did. She explained this in terms of the size of her parents’ garden and the amount of land lying thereabouts. I looked at the metal rungs of the yellow ladder that led down from my top bunk to hers below. I’d never really seen class in terms of stiff rungs or layers, but of continual change and adaptation, as something rather diverting, like picking up shells on a beach, knowing that each one was different, identifying how so, but not saying which was more or bigger or better, or, indeed, less, smaller or worse.

Soon enough, love distracted from class. We were at the next house on the summer progress through Holland, Springendaal. Set in a pine forest close to the German border, this was a gingerbread playhouse for plutocrats built in delicious brown wood and curtained nattily in red and white. This was the house where I learned to put off going to the lavatory for as long as two weeks. It is a trick that is unprofitable; you might say it backfires. But I was scared to go into the woods and crouch and dig and bury. Who was watching? Only God, but still I imposed this mannerly constipation upon myself, afraid of nothing more than my own body. It was merely a physiological version of what I was up to within more perilous recesses in my mind.

Other matters of hygiene were also mortifying. Nicola and I bathed, each with her own enamel basin of cold water, her flannel and soap, out of doors in the heather every morning in the slanty light among the cobweb-silvered heather. She was a perfect little cherub and I was shape-shifting in ways I would rather not notice myself, never mind have anyone else notice.

The air at Springendaal made up for everything. It was as I imagine the air must be in The Magic Mountain, bracing and curative. Although the land was flat the air was drinkable it was so refreshing; something to do with cleanliness and those inhospitable but sweetly breathing pines above.

The family’s large house outside Enschede was named Stokhorst, and it was here that the matriarch, Oma Jannink, lived, to whom, each summer, we paid our respects. It was a high cube of a house with yellow shutters and deep rooms, the kitchen painted that furious strong Dutch blue to keep off flies. The toy cupboard at Stokhorst was marvellous, stuffed with Edwardian dolls, complex tin merry-go-rounds and wonderfully articulated puppets. When we stayed there, the maid, uniformed, brought dry biscuits called beschuiten with strawberries squashed into them and fresh milk when she came to wake us up. Nicola and I generally shared a room.

It was with her cousin Alexander that I fell in love, in no very serious way, but it gave me a repository for my longing to be unaccompanied and to daydream and make up stories. Maybe this longing to be alone is just an attribute of only children, though I’m dead certain Nicola longed to be without me too. No one named Alexander can ever be quite unheroic. I chose Alexander to love because I was really in love with Alexander the Great. The very thought of him at his lessons with Aristotle or astride Bucephalus gave me a thrill.

Nearly all the worst fights that Nicola and I had in our childhood were semantic. She was practical, able, efficient and literal-minded. I was in a place where I could not express myself in language and took refuge in being dreamier and more in-turned than ever.

Nicola knew how to get a rise. She would talk Dutch to herself when we were alone in a room together, or (and she scored every time with this one) she would start to talk about the complete pointlessness of learning Latin and Greek. I still rise to this today. I feel my glands swell, my lecturer’s voice settle in my throat, the old arguments conjugate themselves within my enraged brain. Was it for this the Spartans fell? Tell them, passing stranger.

You can see Nicola’s point.

So we riled one another through these summers and became, probably, quite fond, each of each. I remember that I told her when I had the frightening experience of an elderly maid at Stokhorst getting me to put my tongue into first her parrot’s and then her own mouth. The parrot was an African Grey and its tongue the colour of an unopened black tulip. It was quite dry. The maid’s mouth was wet.

The happiest house, which I remember with love and where the atmosphere of devotion was so strong that one almost dared not spoil it by lazily falling into our bad sniping patterns, was named De Eekhof. This was the home of Christine’s Tante Lida and Oom Nico. They had no children, yet the house was arranged as though for children and the disciplines and routines led to mental ease and stimulation in a way that any family might envy. The maid Helli wore a white kerchief and everything about the kitchen and the dining room and where we played seemed clean but not sterile, and, which is irresistible to a child, even to a very tall one, all our equipment was one size smaller. We played, after our morning swim in the pool that was simply a sandy crater at the end of the garden, with a toy grocer’s shop, its name het Winkeltje (the little shop), that had come from the store of toys at Stokhorst. There were enamel weighing scales, little iron weights, jars of dry goods, small wax paper bags, churns, dippers, ladles, and carved wooden vegetables of every kind. Even when we were too old to play with this toy it was irresistible to us and peace would break out between Nicola and me. There were gravelled walks and flopping buddleia covered with tortoiseshell butterflies. At rest-time, we really did rest, like happy children tired out by play in some ideal of family life. Tante Lida and Oom Nico were cultivated, curious and sophisticated. They left their considerable collection of paintings to the Dutch people. I remember walking dripping after a swim past a picture that I know now was by Monet. There was no fuss. No one ticked me off for my wet footprints. Halfway up the stairs on the way to our bedroom was an automaton we were allowed to play with once a day each. You wound it up and then the real, stuffed, fez-wearing monkey under the glass cloche would begin to do magic tricks, lifting a bowl to reveal a different surprise every time.

The last time I went to De Eekhof I was reluctantly adolescing. Oom Nico took me for a walk. He had read my diary, in which I had written that I was so unhappy I wanted to die.

‘It is a waste of time,’ he said, ‘to be unhappy. And at your age it should be impossible. Believe me, I know. One feels important if one is unhappy. But it could all be so much worse, you know.’ He had the great gentleness to mention no other diary, no other unhappy teenage girl, to be found in Holland no time at all ago.

Oom Nico had hairs growing out of the end of his nose, and large, sad eyes. He wore bifocal spectacles that magnified these eyes. He was bald and was driven to the factory by a chauffeur. The factory made fragrant bales of cotton and printed it gaily. Nicola and I were allowed to choose a bolt each for Christine to sew summer frocks for us. We chose, that last summer, after lunch. Helli had made biftek and afterwards she had drained yoghurt in a cheesecloth and served it with strawberries that had got hot in the sun so that they were between fruit and jam. Nicola chose a white cloth punched with lacy flowers. I chose something pink, feminine and rosaceous, as though for curtains or some large expanse. I chose it for the girl I would have been had I been a better girl. My lukewarm but useful, merely theoretical, crush on Nicola’s cousin Alexander transferred its points completely to devotion and gratitude when Oom Nico said, ‘You will be pretty, you know.’

He had found me out. I had always known that it was lucky I was good at schoolwork because I was so ugly. The odd thing is, why did I not think that this relation, this non-relation, of mine was telling the truth? After all, I couldn’t imagine him telling a lie. During those summers in Holland, I too took a holiday from telling lies.

LENS II: Chapter 3

The first large family in whose cousinhood I tried to affix myself was the great clan of Mitchisons. It was a joke in scientific circles at the time that more than half a ton of human flesh answered to the name Professor Mitchison. Naomi Mitchison, the sister of J.B.S. Haldane, was the matriarch and pivot of the family. She lived to be one hundred and three, the oldest Old Dragon that doughty prep school has yet produced, and one of the first baby Dragons. Doris Lessing has described in her autobiography the atmosphere of intellection at Carradale, the Mitchison house in Argyll. I doubt if I can match her for I recall the passage as absolutely spot on and now of course can’t find it, though maybe I should learn to delegate now I am blind. That would make a drastic and rather late character change.

Naomi was known by her children, her grandchildren and her friends as ‘Nou’. One son, Geoffrey, had died in childhood from meningitis. The death is described by Nou’s friend Aldous Huxley in his novel Point Counter Point. There were five remaining children, Denny, Murdoch, Lois, Avrion, Valentine. Murdoch was Professor of Zoology at Edinburgh, his wife Rosalind Professor of History. Rosalind was known as ‘Rowy’. Rowy had been a close friend of my mother and her daughter Harriet was my friend; each pair of friends was as dissimilar in the same way as the other. That is, where Rowy was effective, certain, dark and convinced, my mother was indecisive, unsure, blonde and ductile; the same was so of Harriet and myself. Harriet’s younger sister Amanda went on to become a journalist who came from the Independent Magazine to interview me. When she was a refinedly pretty little girl, I had, with Harriet, tormented Amanda by telling her long, plotless, essentially theologically based stories about a monster we called the King Devil. I can’t think where we got him from, since the Mitchisons were sternly rationalist and unbelieving. Harriet’s reading tastes ran to The Lord of the Rings, which I could never hack, though I was a sucker for Narnia, so it looks as though I should bear the brunt of the responsibility for the King Devil. When Amanda came to interview me, I felt it only right to give her, in every regard, the upper hand. I was ashamed of my beastly stories in the dark at the commodious Edinburgh house of her childhood. The interview was perfectly nice, though it implied, which may be possible, that my mother’s suicide was the result of incompetence rather than volition. I’ve always comforted myself with the thought that what my mother did was what my mother wanted, but maybe it is good, if sore, to keep an open mind.

Harriet and I both wanted to be doctors. Harriet became one and I still think about it. That’s a difference between us.

The village of Carradale lies in a bay on the eastern edge of the Mull of Kintyre. In recent years, it has been tragically newsworthy because almost every member of its small fishing fleet was drowned. That guts a community for generations.

The big house was harled and painted white, pepperpotted and roofed in slate the colour of lavender when dry, of thunder when wet. There were never, it seemed to me, fewer than twenty adults in the house at a time, always a few babies and then there were middlies and, what we were becoming, teenagers. That I did not fall completely into internal delinquency is almost certainly due to the Mitchisons, Rowy at the core of it, but all those others each of whose names I can remember, with their faces, for ever, at the age they were when I was turning twelve, though most of them now are professors themselves and members of the intelligentsia, whatever it is now called. Certainly not the ‘chattering classes’. They were nothing as trivial as chatterers, rather forceful, indeed irresistible, asserters.

During our teenage years, we were sent to sleep at The Mains, the Scots word for the home farm. This was a sensible decision. Dressing for dinner took me about four hours, though I’ve never met a vain Mitchison, including those who possessed beauty: Clare and Kate, Mary, Valentine and Josh. It was in the bathroom at The Mains that I first saw underwear made for the delectation of men rather than at the behest of spinsters. It had been hand-washed, evidently, and was dependent from the taps of a washbasin in the freezing bathroom. It was at once very small and very emphatic, lacy, red, and belonging to the girlfriend of Francis Huxley.

The drawing room in the big house was full of the sort of silence that is made by eight or nine good-quality brains working hard and separately, absolutely not a library silence, more like being in a vast digestive system. Small, fierce Naomi sat typing at her desk that looked out over the unsmooth Highland lawn, a hedge of Rugosa roses, the path to the sea, Carradale Point itself and the sea beyond. She wrote well over ninety books. The light in the room was low and seemed to be green. There was a sizeable mobile made of metal fish that very probably interpreted Darwinian theory.

In the plain, loaded shelves was a tan first edition inscribed to Nou by its author of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, on top of which I had one Easter found a chocolate egg hidden. This was a rare success for me since the annual egg-hunt clues had as a rule a scientific and mathematical bias, with a strong seam of Scottish history. After Nou’s death, this volume went up to auction and I saw it again in a newspaper; what it was and what it meant to me so separate.

Nou was, in addition to being an Argyllshire councillor, though devoid of any whiff of landlordism or lairdliness, Mother of the Bakgatla tribe in Botswana, and frequently one or more of her honorary Bakgatla children would be staying at the big house.

Nobody said, but Nou, as well as coming from the intellectual purple, was also, though it infuriated her to be addressed thus, Lady Mitchison. Her late husband had been made a Labour life peer. I mention this at all only to introduce the ticklish subject of what to call the people who worked for her, since she was at once so clearly the product of at least two kinds of aristocracy and a good old-fashioned Red.

One evening we older children were asked by Percy, who did the gardening, although one did not call him the gardener, to gather caterpillars from the kitchen garden. The cabbage white has a caterpillar that is fat and striped like a wedding cravat; when you pick it up it looks interested at both ends. We took our catch, if you can call anything as docile as a few bowls of caterpillars a catch, in to Nellie, who certainly was not the cook.

The caterpillars, dipped in flour and nicely fried, appeared as the first course that night in deference to the palates of Nou’s guests from Botswana.

The dining table was enormous, thick, not polished but raw wood, aged, stained, practical; it was a rectangle with curved ends; there must be a geometrical term for this figure but I lack it. I do not mean an ellipse. There seemed in that atmosphere of intellectual certainty so little that was elliptical in the way my father was in person and in the way his mind worked. I am ashamed to say that I escaped from his intelligent failures of certainty to the Mitchisons’ apparent categoricalness with the cowardice that goes with a callow mind aspin. My father’s way offered no shelter, while that of the Mitchisons offered much of it and, or so it seemed, to spare. I was, as I am not now, sick for certainties. I now find them infertile and too often rooted in prejudice.

I wonder now whether I was ever actually invited at all to Carradale or whether I just hid within one family or another’s capacious kindness: Rowy was kind all through my youth in a sort of improvement on her late friend, my mother’s, way. An improvement, I mean, in that Rowy was alive. Nou’s daughter-in-law Lorna, married to Av (Nicholas Avrion in full, meaning the Victory of the People), came from Skye and always seemed to be carrying a baby in her arms. She never raised her voice and had the balanced selflessness that comes to only very few mothers. She was impossible to lie to. It was Ruth, Naomi’s oldest daughter-in-law, whom I loved and to whom I clung like stickyweed for years, though she never complained about it, even when I started sticking to her in the South as well. She was not a physically large person, nor did she shout. She seemed to see a great deal and to interpret it correctly but in silence. She was a doctor, musical, wore slim brown or grey shirts and sat at a tangent to the table. She was tangential in manner yet direct in thought; a mode I find increasingly appealing the longer I live. I wish she were alive now; hers was a singular note amid so much information and embodied, biological almost, confidence.

At the far end of the dining room was a sizeable brown painting, thickly impastoed. It was known as ‘The Goat in the Custard’, and worked surprisingly well as a splashback for the kippers that were left for each individual to fry for him or herself at breakfast, in a then remarkable item of culinary equipment, an electric frying pan. It is a miracle that the house smelt not of frying red herrings but of heather, wood, pipe smoke and wool. Heather smells like dust and honey both. Intellectuals smoked pipes then.

Sometimes, a piper would come up from Lochgilphead, and, perhaps, a squeezebox player, and we would dance in the library, which was called the ping-pong room. Nou, short, dense, wore garments of fantastic tribal splendour and simultaneous rationality, sandals, bright yet serious skirts and perhaps a serape or sash in acknowledgement of one or another of her encyclopaedic interests and convictions. She was unbending, solid, frowning; she looked like strength itself, like an animal, an armadillo or a Galapagos tortoise; absolutely not a pangolin. The pangolin looks as though his armour has only recently been donned. Nou was born in hers. She danced in a stately manner that attested to her sublime physical confidence. She was an advocate of the benefits of free love. I feared to be addressed by her, yet longed to get a smile from her. I felt easier in her house when she was not in the room and that this is not a particularly healthy state of mind. I do not think that she cared much for my mother or me; even as lame ducks, a class for which Nou had time, we were not interestingly lamed. I can imagine my mother getting Carradale all wrong, talking in the drawing room during the daytime or gossiping or noticing clothes or foods or smells. Certainly she would be overdressed. We were there together only one time, when I was two, so I cannot speak for her outfit during that summer of 1957.