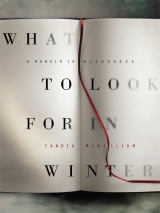

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

LENS II: Chapter 2

In the life of the present I am reading, that is listening to, Paradise Lost. It is read by Anton Lesser, whose intelligent doubt-filled voice somehow emphasises the clouded giants and rivers of pearl he speaks of through the mind of Milton. So far in my blindness only my accountant has been sufficiently innocent and jolly to mention Milton to me, over the receipts.

How consoling and terrifying it was to hear the words: ‘the mind is its own place; and in itself / can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven’. When first I became blind, Fram, who lives sixty miles away, suggested that I would never be quite alone because I have ‘my art’. I felt at once consigned to live off something that I was not talented or morally courageous enough to address. It was like telling a deer to build its future around raw meat. I’m doing my best and I’m quite aware that whatever my ‘art’ was, it will have been changed by my blindness. It remains to be seen, if I may use that word, how. I was never alone when I could read.

My parents and I visited England only for very specific familial reasons. I was always carsick and usually moving between anxiety and terror, relieved by daydreams, at this period all about being a doctor of great bravery during a selection of historical scenarios; I suspect I was usually disguised as a boy in these roles. My father had never passed a driving test, braked on corners and both parents smoked in the fuggy leather cupboard that was our car within. It wasn’t our car, really, but the National Trust for Scotland’s. This non-ownership was significant to my sense of our hardly holding on to our ledge in life.

Our reasons for visiting England included my parents’ bookseller friend Ben Weinreb and his family. Ben gave me the dummy of a book called London 2000 to draw in. Both date and city seemed lifetimes distant from me and my life; now we are years beyond it and Ben is dead. We visited other friends, a couple called Myrtle and Bear; he was known as Bear, since, as a diabetic, he couldn’t have sweet things. He too was a book dealer. Myrtle was a potter. There were some rather glamorous friends in Hampstead, he perhaps a sculptor, she certainly a sexpot. She struck me as the best sort of sexpot because her warmth went out in all directions, not merely to men.

The main reason that we ever went as a family to England was to visit grandparents. This was never comfortable. My widowed paternal grandmother lived at Windsor Castle in a tiny house in the cloister that nonetheless had a speaking tube to call long-departed servants. She had been a nurse at Great Ormond Street Hospital and bore the loss of her husband with a daily exercised Christian faith and ingrained modest fortitude. My grandfather, Ormiston Galloway Edgar McWilliam, a man whose temperament was made for peace and the arts of peace, fought as a teenager in the trenches in the Great War and was killed at the end of the Second World War while laying a smokescreen in the tail end of an aeroplane that was shot down, I believe, by our own side. Among his close friends was the painter Henry Lamb, and the letters between them show a relish for family life and a sensitivity to preposterousness both at war and in the smaller frays of family life. Lamb’s letters are often illustrated with quick sketches of his children being dried after a bath, paddling and so on. In one of his letters my grandfather describes tucking my six-year-old father back into bed after the child had been awoken by the flare and crackings of the Crystal Palace burning down, of which my grandfather gives an eyewitness account. My grandfather wrote and illustrated a published book before he was twenty. It is about the battle at Suvla. He must have known he was going to die then.

But he didn’t, or not in that war. I have the photographs of him as the captain of both rugby and cricket teams at Charterhouse. On the back of each photograph he has written in almost every case the date and place where each smiling young man in the fading picture had fallen in war.

His widow, my grandmother’s was not a false piety; she was a deeply believing Anglican whose daily notebooks used to shock me with their probity when I was ten and thought I knew a lot. Clearly I knew nothing. What decent child goes through the notebooks of her grandmother? Each day she recorded the church services she had attended, to whom she had written, and from whom she had received, letters, and how much money she had spent. The amounts were very small. She had an expressed quality of humility that enraged my mother and there is no doubt at all that my humble grandmother looked very far down upon her tall, ostensibly worldly daughter-in-law. The word, though it was never used, would have been ‘vulgar’. Certainly my paternal grandmother regarded my maternal grand parents as being ‘not quite…’ or, that damning deprecation, ‘too grand for us’.

My mother teased my father unkindly about his attachment to his mother and referred to her mother-in-law, also unkindly, as ‘Navy Blue Throughout’. These had been the words that my grandmother had replied with when my mother’s mother asked her what she would be wearing to the wedding that would conjoin their ill-matched families.

I called my paternal grandmother ‘Grand’mère’. I suspect this was to get over some difficulty about my own mother refusing to address her as ‘Mother’, as convention might then have asked. In due time, my stepmother would address her thus.

My mother’s own mother wasn’t that fond of Mummy either. My grandmother Clara was from theatre people; her own mother and grandmother, with their long beautiful legs, had been male impersonators on the stage. My maternal great-grandmother was a friend of Vesta Tilley. There are lost photographs of my transvestite ancestresses looking wonderful in tails and tights. How I wish I had them now. I packed them away in a trunk before I moved into my first marital home. The trunk was stored by a friend. The friend died sadly, surprisingly, dreadfully, young. How could I even mention my trunk of keepsakes to a family that had lost its head? As it is, the trunk of travesties sounds like the framing device for one of those dull novels that are meant to show us some flat tale of parallel lives separated only by time, whose moral is that we are all sisters under the skin. I worry, too, that my long-lost trunk may contain things of which I might be ashamed, satin trousers, proposals of marriage, lists of things to do that will resemble in every way those lists I write thirty-five years on.

Neither Mummy nor I inherited the great legs. My grandmother Clara’s first speaking role on the stage was as Little Lord Fauntleroy, aged five. She was so symmetrically and astoundingly elongated and so facially beautiful that she was continually stopped on the street. I have one photo of her, singing the part of Mad Margaret in Ruddigore. Considering the town’s later importance in my life, it is odd that I should, for the earliest part of it, have thought that ‘Basingstoke’ was an invented word that you employed to calm female lunatics. In the Mad Margaret photograph, my glorious grandmother’s glorious hair reaches to her calves. Later when she cut it off her father, who owned a string of theatres in the East End and on the South Coast, didn’t speak to her for months. He could eat twelve dozen oysters at a sitting. My grandmother Clara was known as Clare; she had two sisters, Ruth and Edna. Edna married and lived in Guernsey, impossibly exotic. I remember meeting Great-Aunt Edna only once, during a half-term out from my English school. We sat in some silence. Nobody’s accent sounded real except my grandmother’s self-invented grande dame tones. Poor, blind Ruth became a counter in my parents’ stony game that no one could win.

My father was a dab hand at playing ducks and drakes, making flat stones bounce off the, I suppose, epilimnion. As their marriage worsened, my mother would say, ‘Throwing stones can blind people. My Aunt Ruth was blinded, aged seven, for life by a boy throwing stones.’

You could see my father was getting bored with my mother. This boredom made her anxious. I was anxious for them both, with their separate damaged hearts. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know that my father’s heart was literally fragile since he had had rheumatic fever during his National Service. He was meant to avoid physical risk and exertion; of course he didn’t. And since I lived with my face as far up my mother’s sleeve as I could get it, so as to smell her, I knew all about the heart that was worn there too.

Our visits to my maternal grandparents were approached with sublimated satire and some dread by my father. God knows how my mother felt. I think the person with whom she was easiest was Ernest, who had been her father’s soldier-servant and stayed on. She was adored by Ernest in a way that she was not by her parents to whom her gender, height, appearance and marriage were all a disappointment. Her father called her ‘Scruff’, not kindly meant.

The Folly, West Drive, Sonning-on-Thames, Berkshire, was England to me, and how it scared and stifled me. I could not then have placed what it was about this single-storey brick residence made, as I could never forget, with my grandfather’s blood, toil, tears and sweat, that took the air out of me but I never entered it without knowing I was going into another country where they did things differently. I recognised the claustrophobia when encountering it again in Elizabeth Bowen’s great wartime novel about escape from a certain England, The Heat of the Day. There is in it a house called Holme Deane, that is not The Folly, naturally, but has some of its effect.

I don’t eat ham or pork, sausages or bacon. I have a number of Jewish friends who really like sausages or will eat a bacon sandwich. My refusal to eat pig-meat started off as a gesture of wholly pointless identification, and maybe its motives aren’t as grand as I thought they were, when I was seven. Maybe they are a pettifogging, grandiose and utterly pointless boycotting of a certain England. I was scared of the flatness, the enclosure, the sense of being tinned. One could not, as in a home in the North, stretch and shout and breathe in and out. One was in a tin and on a shelf and set in place, the place to be, to sit and stay sat, set.

Ham and salad was what we had for lunch at The Folly, the ham like big wet hangnails, the salad made of units, one lettuce leaf, a quarter of tomato, a slice of egg, a pinch of cress, and that incontinent flitch of beetroot. My father loved Heinz Salad Cream and got his lunch down with the help of this; for pudding it was ice cream and tinned fruit salad. This was for the times a perfectly festive family meal. My mother had spoiled me by her Italianising of our life, her olive oil, aubergines, herbs. At The Folly, meals were taken because what you did at one o’clock was have lunch. It was almost an act of patriotism, a contribution to the resettlement of the world post-war, the healing deployment of routine against chaos or otherness.

My father, never a fan in other circumstance of healthy food, would ‘forget’ not to say, ‘Do you know, Clare, that Wall’s make pork pies too and that this ice cream is probably – delicious of course – pork fat with a bit of air whipped in?’ This was mean of him as he consumed quantities of Wall’s all his life, regarding it as a special delicacy not perhaps related to real ice cream, certainly not to ice cream in Italy or as made by the Italian immigrants to Scotland, Mr Lucca at Musselburgh, Mr Coia at the end of the Crescent, Mr Nardini at Largs, but certainly a treat in itself. This was the man, after all, who, when Lyons Maid brought out the new line in lollies they called a Fab, with hundreds and thousands on the chocolate tip, spent a weekend afternoon chasing one down.

I think my Christian name was a bother to my Henderson grandparents. It was ostentatious, foreign and pretentious; they had not heard it before. Grandpapa did not like what he did not know. Of course they were defensive; there had just been a world war; they had but the one child, who seemed to have decided to marry a man who was not only uninterested in making money but deprecated the process and the idea of a society arranged around it.

My grandmothers addressed one another as ‘Mrs Henderson’ and ‘Mrs McWilliam’.

It is all unspeakable and it was all about class, tone and education. My maternal grandmother, despite her beauty, a dowry that can re assure a man who purchases it that there has been a straight swap with no small print, was cleverer than she dared show her husband. He was older and controlled the purse-strings. She cleaned the house, starting at five in the morning every day, wearing what she called a ‘house dress’ before she changed into her proper – on show – clothes for that day’s part, and brushing her regrown waist-length hair one hundred times before dividing it into six, making plaits and coiling it up like Dorothea Brooke’s crown of hair in Middlemarch. She did the housework daily like this although there was Ernest’s wife Florrie to ‘do’ for her. Yet it was at The Folly that I found one of the books that changed my life. It had been my mother’s. It was a big coral-coloured cloth-bound book containing black-and-white reproductions of old master paintings and modern works with captions encouraging you to look harder into the picture. It had been published during the war and has something of the perspicacity of Kenneth Clark’s One Hundred Details. It was written by someone called Ana M. Berry and now belongs to my children. It must have taken faith in civilisation to produce such a book at such a time. Its name is Art for Children.

All her frustration my grandmother poured into systems of control that eventually grew inwards and harmed her. She was so proud; she would like it to be said of her that she never took a penny from the state, that her home was spotless, that she was a good wife, that she had kept her figure, that she wasted nothing. I think now that inside her stone self was a good deal more sweetness. I think that she was lonely and used pride and dignity to kill pain, in so doing closing over her heart an awful fist of calcification till it resembled flint and was not. All the creative dash she had been born with in the Mile End Road, where she’d kept her ponies as a little girl, she turned to producing light opera and operetta for the Sainsbury Singers of Reading, who became as family to her.

McWilliams think Verdi vulgar (I don’t. Don Carlos is my favourite). I learned about my father not caring for Verdi at the very start of the existence of the Sony Walkman. Daddy was in a ward of old men after his stroke. I flew north to see him with this exciting new invention and a stack of Verdi on tape, all in cellophane. Daddy, who had an immoderate passion for the NHS, was even quite chatty to me, and introduced me to a new friend he had made in the next-door bed.

‘Bob, this is my daughter, Candy’, said Daddy. ‘She is not a very keen swimmer as far as I know.’

He explained to me later, as he ate with real gusto his eleven o’clock lunch of Finnan haddock with extra bones and mashed tatties, ‘Bob likes girls. His daughter was a local swimming champion. He had an unfortunate experience with her and was sent to prison. He’s a charming fellow. Do you like Verdi, Candybox? I don’t think I could bear him at all up close.’ Long before it was fashionable to be keen on Handel as a composer of opera, Daddy was. I took my Verdi tapes back to England. We never had the time together to find that we both adored Britten and that I am nearing his feeling that Richard Strauss is the sexiest of composers, though I first met him in the Four Last Songs when I was sternly above sex, being fifteen and torridly in love, at that point, with one who was as remote and cool as the North Star.

I do not know why music should cause more curdling in matters of taste than literature, but so it sometimes seems. My parents’ parents each mistrusted the other’s form of musicality, taking it, unfairly and unsubtly, on either side, as a metaphor for much more.

I loved each of my grandmothers for physical reasons: my McWilliam grandmother had a nice little bob held in place with a kirby grip and read nineteenth-century novels to me; she had catch-phrases such as ‘Would patrons care for a cup of hot chocolate?’, and ‘Would you v.s.k. close the door?’ where v.s.k. stood for ‘very sweetly kindly’. My Henderson grandmother I loved for her waistline, her ankles, her deep voice, her extraordinarily stagey diction; but I knew to be afraid of her. She believed in posture, in scouring, and in never complaining. I never sensed that she had faith in anything but the joy music gave her and in discipline, while my other grandmother was suffused by her religious faith and knew and played ecclesiastical music.

We took a trip to the Highlands with my maternal grandparents. Grandpapa kept his Homburg hat on his left knee all the time he was in the car and on his head all the time he was out of it. He held on to the leather strap that cars had at the time in the back as we drove up to Blair Atholl and other photogenic castles. The idea may have been to convince my grandparents of the respectability of my father’s source of employment. My grandpapa Douglas Henderson was a pure Scot, his wife an Irish-Scot. It was impossible to detect any reaction to the operatic landscapes we were toiling among, no reaction save to changes of temperature in that claustrophobic vehicle. Although my grandmother on my mother’s side was a woman of habitual kindness, she was perhaps not kind to her own daughter. My grandfather simply was unkind to her. At over six foot, my mother was nonetheless a woman who expected to be knocked about.

We made forays to England, obedient to the proprieties of family life. Things at home were tightening up. My father crashed his car on the edge of Duddingston Loch, upon whose frozen epilimnion the Reverend Walker serenely skates in the famous painting. The car was of course not his but that of the National Trust for Scotland. Daddy had been driving on ice, and fast. There was but one tree on the edge of Duddingston Loch and that tree it was that saved my father’s life; the car’s registration number was LSD 414, in those days when LSD stood for money: pounds, shillings and pence.

I was beginning to start trying to stay the night with friends in order to avoid either the silence when he was not there or the shouting when he was. My mother cannot have been easy. She longed to work, she was lonely and dislocated; and yet she continued to pour into me the sort of imaginative care that may so easily be put out by what we nowadays have learned to recognise as depression. For there is no doubt that my mother was a woman in despair at a time when divorce except among the uninhibited rich or the very free-thinking was an extinguishing scandal and when a woman’s portion was her husband’s.

There is the awful irony that when a marriage is most in danger the couple behaves in exactly the way guaranteed to rile, madden and repel one another. If only they might be nudged to recover their actual as opposed to monster selves, the marriage might yet survive.

In this case, such a thing was not possible and did not happen. Matters were moving too fast, in ways that I could sense but could not know. It was a little ship, someone else was coming aboard and my mother took what I am convinced she thought was the most logical, kind and unselfish step that she might take for the sake of her husband and her child. She jumped ship. She couldn’t see another way.

I had always been a pamphleteer, boring my father with various documents that I had carefully written out in extravagant proclamatory hands. I remember writing a lot about the tensions between Greeks and Turks in Cyprus, and I devoted screeds to the long dying and eventual death of Pope John XXIII. I never wrote a word about this disaster nearer to home.

My mother loved clothes that sparkled. She made a mauve silk ballerina-length skirt and bought to match it a mauve polo neck shot with silver. It was her best party outfit and before putting the polo neck over her face she would wrap her whole head in a chiffon veil so as not to mark the polo neck with make-up. She spent days deciding whether or not to wash these garments by hand with Lux Flakes or to take them to the, costly, dry cleaner.

Without conscious intention I wore on the occasion of my engagement to my first husband, a mauve silk ballerina-length skirt with a mauve sparkly T-shirt. Someone, of course, spilt red wine all over me and I remembered then that I must not send these symbolic clothes to the dry cleaner or they would come back only after I had died. I hand-washed them and they are my daughter’s now.

I suppose my mother’s sparkly mauve party outfit went, all nicely dry-cleaned, to the shop known as the ‘Dead Women’s’, where she did a lot of clothes shopping herself during her short spell as a living woman.

To be asked to be stepmother to any child must be an alarming prospect. To be asked to be the stepmother of a grief-stricken solitary with nearly a yard of hair must be devastating. Nonetheless, at the age of twenty-seven, in the April after the October of my mother’s death, my Dutch stepmother Christine Jannink took me on.

Christine’s parents, Dutch though they were, lived in another England, very far from The Folly in Sonning, on a farm that reached down to the banks of the River Wye and ran to other routines entirely. The routines at Llangetts, near Ross-on-Wye, ran on a mixture of ultra-English and ultra-Dutch lines that were to me both exhausting and really quite exciting.

At the wedding reception I sat under the festive table on which lay a long pink fish taken from the river, and I eavesdropped. The flowers my stepmother had chosen for her bouquet were white and yellow freesias and also, more unusually, the velvet black Iris tuberosa, more usually known as the widow iris.

The men wore buttonholes of this same velvety flower. It remains, peculiarly, one of the flowers that I most love and I first saw it on that day. It is associated with the best in my life; I thank its gardener for that, and my stepmother too.

My stepmother’s clever needle had run me up a coffee-coloured raw-silk frock. Unlike almost all brides, but just like an ugly sister, I got fatter and fatter as the wedding approached. My stepmother let in a cunning broderie anglaise panel across my stout front.

Although I was never able, without complicated feelings of disloyalty towards my mother, to address my stepmother as ‘Mum’, as she wished, I was able to call the grower of those irises ‘Mama’. I loved my bossy Dutch step-grandmother at once and with passionate feeling. Here was someone, I felt, as I sulked under the long pink and silver fish and the concealing damask cloth that covered the festive wedding-breakfast table, someone with kindness and style who had got through something very dreadful, the war, occupation, flight, and survived with love to spare.

Oddly for an only child, I had never had an imaginary friend. But now I was to have a real, pretty, new friend, about whom I’d heard such a lovely lot.

We had first been brought together, my new friend and step-aunt, two years my junior, the Christmas before. It cannot have been easy for any of the adults but they acquitted themselves nobly. Nicola, my stepmother’s adored baby sister, was the fourth and late child of her handsome parents. So special was she that she had been given the first name ‘Engelbertha’, literally brought by the angels.

She was being asked to love a gigantic ruffian in a kilt, two years older and ten sizes bigger than herself, with an inner life populated very considerably by the ancient world, North Britain and death.

Nicola no sooner looked than she loathed. I no sooner looked than, I guess, I envied. We were to learn over the next few years how veritably to torment one another.

Rushing up to the surface of today, no doubt in shame, I should tell you that while Liv has kept her chair at the computer, I have vacated mine at her side. This has been taken over by one of the two other personalities as well as my own that poor Liv has to deal with daily as we write this book together. Rita, the Russian Blue cat, who has the sagging undercarriage common to spayed queen cats, has turfed me out of my chair and I’m on a piano stool. Yesterday her resting place of choice was the so-comfortable computer keyboard, so we had to exile her. Today she is taking her revenge. The other cat, Ormiston, whom Rita disdains, and who resembles a minky koala bear with an owl’s face and leaves tennis-ball-sized clots of fluff everywhere, is outdoors pretending to be a dog. His loyalty, kindness and obedience are among the many reasons that Rita despises him. She takes much more seriously her feline duties, being spiteful, sneaky, narcissistic, and almost purely selfish. Her triangular face, large turquoise-emerald eyes, long legs and ever-questioning silver tail mark her out as what she is, a beauty from Archangel, a double-coated ship’s cat, used to men and to small territory. She very clearly prefers men to women and cannot abide the smell of any products made by Elizabeth Arden. I run all my scents past her for approval. If only she did the same for me.

Smell becomes very important as sight is lost and one scent that at once wakens me in the night is that of Rita when she has decided to take a territorial stand against the feral cat who lives in the Royal Hospital Gardens that are over the wall from the garden of where I am living. Cat’s pee wakes me up as quick as a flash. At the last count, there were at least thirty-nine foxes in the Royal Hospital Gardens. Today, as I write (Liv is ill so I’m tapping blindly myself), it is the first day of the RHS Flower Show, so the foxes will have much new excitement to look at and chew on and tonight a fox may look at a Queen.

My poor stepmother had to deal with a stepchild itself almost feral. There was so much that, aged nine, I simply did not know was essential to the sustaining of normal everyday life. Brought up in a large prosperous house with siblings and staff and a mother with a talent for domestic organisation, my stepmother was faced with a sullen lump who knew nothing of the arts of husbandry or of the activities of any proper, let us say accompanied, child. As she understood it, I did not even know how to play properly. Her own father had won a gold medal for hockey at the Olympics, she had played at junior Wimbledon, her brother had been athletic at Winchester, as a family they went to Switzerland each year for what they called the ‘wintersporting’. Her nursery life had involved games not of the imagination alone but with equipment and rules and competition. I was physically inert and evinced not even much mental movement. My stepmother called me once the least curious child she had ever known. We were walking along the Crescent at the time. I was of course thinking about myself and how I was perceived (I was by then in double figures). Did people think I was the au pair? I was wondering at that precise moment, the moment of my condemnation for incuriosity. But that was to come.

The first thing that had to go was my fat. Christine instituted the healthy habit of a run before breakfast. She monitored my diet with maternal care. My father and she made an attractive pair of newlyweds. My father always looked younger than his age and they were patently content in and respectful of one another’s company.

But there was me. Even as I diminished in size, I did not diminish in number and this cannot have been easy for either of them.

Thorough regime change commenced. My mother’s cats were destroyed, her yellow Labrador Katie sent to go and live therapeutically with the inmates of a lunatic asylum. I was given a blue budgerigar, whose death by careless starvation remains on my conscience. Nicola had at the same time been given a green budgerigar that lived a long and, one can only presume, happy life. Budgies don’t confide much. I named mine Sebastian. I do not like the proximity of birds; they are like escaped hearts in full panic, beating, beating, unable to help you to help them, unsusceptible to rational appeal, flickering, filamented, electric, random.

I was learning systematically to lie. Frequently these lies were pointless, for example that I had to stay late at school on account of a play I was in, when of course there was no play and I just didn’t want to go home.

I was hopeless with money so my stepmother initiated an account book; we did the accounts after Saturday breakfast, after my run and before I cleaned the brass. Our front door had the numerals 2 and 7 in brass, a letterbox, a large handle, a keyhole-plate, and to the right, set in stone, a square bell-pull of chaste Georgian elegance. There was the brass threshold cover and all the internal door handles and elegant acorn-tipped window raisers to do as well. I preferred using Duraglit wadding to Brasso and a cloth, because I was wasteful with Brasso and tended to splash it on surrounding painted areas.

The large square bell-pull was most rewarding. Was this because the neighbours could see that I was a good girl really, as I polished, those Saturday mornings?

Together, with their pared-back taste, my father and his new wife overhauled the house that had been so reassuringly stuffed and quite possibly unhygienic in my mother’s time. New spaces were made; a modern airiness not unfaithful to the Georgian whole prevailed. The tatty affectations of my mother’s gardening were levelled and a new aptness of intelligent planning for a growing family introduced.

Routine appeared where it had very probably culpably never been before. A goat’s bell was rung at mealtimes. Grace was said. Appropriate napery attended every meal. I laid the table for breakfast before I went to bed. A wedding gift of good china, navy blue vine leaves on ridged white porcelain, was the everyday service. There was other, Dutch, ancestral china for dinner parties. My stepmother’s magical needle confected dressings for every tall window and my father stencilled or carpentered witty architectural effects throughout the now, it seemed, much larger house.