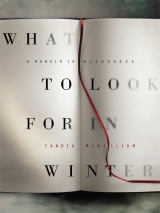

Текст книги "What to Look for in Winter"

Автор книги: Candia McWilliam

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

LENS II: Chapter 6

If my own is a story of uprooting and its effects, so is that of my first husband, about whom I shall take the course of writing as little as he would wish. We married in love and in good faith and are the parents of two beloved children. We come high in one another’s lives and have only kind thoughts for one another. We are both of a romantic temperament, both shy and both with an instinct to place trust in a metaphysical belief system that includes God. Quentin is a confirmed Christian. When I stand next to him in church, which I do quite frequently, I feel my own shaky faith strengthened by the directness of his.

I did not become confirmed when the opportunity to be so arrived at boarding school, taking the pi line that most of the other girls were doing it to please their parents and to get a nice string of pearls or a pretty diamond cross. I should have become confirmed then, because it would have so pleased my McWilliam grandmother. Quentin’s story of deracination and its redress is geographically (and in other ways) more dramatic than my own and I shall tell it sparely. Born in Spain, he was a young child in Australia. He loves the sea and ships. At a very tender age, he was sent to prep school at Farleigh House School. His grandfather, sensing after the war that big houses might be doomed, had leased his own to this institution, a primarily Roman Catholic prep school, and moved to Kenya. Thus Quentin was at school among boys of a different religious denomination; he had an Australian accent and was being schooled in a house that was, actually, his own. While he keeps many friends from those days, it was greatly to his satisfaction when the lease expired in 1983 to be able to restore and to re-enter his ancestors’ home. The school relocated to Red Rice in Andover. There is now no sense to the house that it ever was anything but a happy family home. People who were at the school are astonished by the difference.

One way of being evasive in a memoir or whatever it is that my mouth is making in an attempt to get my eyes to open, is to take refuge, as Anthony Powell so gruesomely enjoyably and teasingly does in his own memoirs, in genealogy. I shan’t do that. Histories of the Wallop family may be found elsewhere.

Perhaps the most humanly relevant fact about the Wallop family is that they are known as the Red Earls on account of the heir more often than not having ruby-red hair. Our son Oliver, who was named for Cromwell – one of the Wallops was a regicide – was born on 22 December 1981. His names are also Henry Rufus. I got to choose this third quite unrejectable name. As soon as a little bit of the baby’s head was visible, Quentin was convinced that he would be a boy, and a boy indeed he was, with a fiery head, at birth and ever since, of scarlet hair. It was a hard snowy winter and we spent Christmas at Basingstoke District Hospital, dizzy with joy and completely ignorant of how to feed our huge son. The NHS gave us a knitted Santa which is still in the day nursery at Farleigh. It was the middle of the shooting season, so Quentin would be busy in the day and then slide in his Land Rover back to me in the hospital with big dishes of salami that he had bought at I Camisa in Soho and sliced paper thin. Other mothers who gave birth in December 1981 may remember this handsome man handing around plates of cured Italian meats in his delight at being a father, and it was indeed to be a father that Quentin himself was born. His story of deracination makes for an absolute fix on steadiness as a parent.

Our honeymoon took place in Mexico. I had forgotten to get an American visa and even Mr Potts couldn’t swing it. This time, the crazy luck came from the fact that Papa was very briefly a Minister of State for Defence under Mrs Thatcher, who sacked him I think for being too left-wing; ‘wet’ was the word of the day. Phone calls were made and on our stopover in Los Angeles I was guarded, including on ‘comfort visits’, by armed police. Quentin is an experienced, hardy, courageous, adventurous and curious traveller. He was completely thrown to discover that he had married someone who turned to jelly at the thought of arranging a train trip from Basingstoke to London. He says that I offered to do the washing-up on our first long-haul flight together. In those days there was a sort of drawing room in the forehead of very fat aeroplanes, which I used to like. It felt solid. It was like being a citizen of Celesteville, Babar’s immaculately rational and so French city, all curves and absence of threat, while sitting up in the top of those fat jumbos.

We arrived in Mexico City in the middle of the night. I sent my sparkly pink and grey going-away outfit to the dry cleaner and, true to form, it returned doll-sized the next day. It made for a good grounding that I had read Under the Volcano so many times

But I was completely unprepared to conceive of the minds that could build the pyramids of unmortared stone that we climbed in the Yucatan. The solidity of such abstraction, the mathematical judgement and forethought required to cut each constituent stone just so and to cut it but with another stone, that obsidian axe, all this not only overwhelmed but terrified me. I found myself thinking about their thought and failing to conceive of how even to begin to think about it. It argued mental processes of such developed abstraction, whose result was transformed into something solid, and that felt deathly itself. There were no merciful flaws, was no tolerance of looseness.

It is common knowledge that the Mexicans go and picnic on the graves of their ancestors, taking food for the dear dead. Perhaps that was what I couldn’t supply imaginatively as I stood in the court where allegedly a game had been played with human heads, or when I looked into the stone face of the rain god Chac Mool at the summit of one of the pyramids. It was a relief to see that his uncomfortable pose and lugubrious features looked exactly like James Fergusson, who would have made an improbable Mayan.

In between visits in the dawn before the great heat rolled over these ancient sites, we drove with our guide Mr Cervantes, prodigiously belted around his generous tum, and visited churches whose inner gold was like being swallowed by the burning sun itself, though they were lit low and only brushed by little candles.

In Oaxaca, I was briefly kidnapped. Quentin found me in the police station. There had been a misunderstanding and a perfectly genial crowd of kidnappers had thought I was Jimmy Connors’s new wife, who was apparently a Playmate of the Year in Playboy magazine.

In the way of new couples in a new place, we found ‘our’ restaurant and ‘our’ waiter. We fell for an elderly waiter whose deep melancholic physiognomy was so paintable, so Spanish, that he seemed to have walked straight from the frame of a painting by Velázquez. Having been born in Spain, on the feast of Santiago, Quentin has an affinity with Spaniards, though a Mexican Spaniard is another kind of Spaniard. I feel a strong attraction to that Spanish Greek, El Greco, born in Candia.

It was at the metal table tended by this beautiful waiter, wrapped in his pure white apron, that I learned that of all spirituous liquors, tequila is to me the most dangerous and powerful. I saw black visions. The iguanas didn’t help, purposeful and with empty eyes. They look repulsively knowledgeable, hardenedly social.

Quentin had planned in detail a long honeymoon involving deeper penetration of the jungle – to see Mayan ruins – than we eventually made. We spent some time self-catering in Cancún, an outpost of one kind of American civilisation. When I say self-catering, I mean that we got shy of the communal dining room of the resort we found ourselves in. Somehow it was common knowledge that we were newlyweds and the combination of being serenaded and of not giggling at the menu (‘Pork Chops Deutsch’ got us every time) drove us to spend time in our little cabin on the beach. Since he had been to Mexico before, Quentin had developed a taste for Huevos Rancheros; since I was in love, I ate them too. The other thing we lived on was avocados. I never became quite used to the flat-footed arrival into our bedroom of a grumpy seven-foot-long iguana, who seemed to want to play. He did that thing that creatures in thumpingly hot countries do of staying very still indeed and then making a sudden movement that chills the blood. I think he was in love with Quentin too and wanted to drive us apart. He certainly saw it as his business to guard Quentin from any overtures from me. He was very dusty and I wondered whether he was polished at all underneath. His sides ticked. He stood, it seemed to me, for disappointment, aridity and a general sense of having missed the party. There was no reasoning with him.

In the end, for a Malcolm Lowry fan, it was the perfect way for a Mexican honeymoon to come to a halt. We ran out of money. Quentin, who is good at that sort of thing, made several phone calls. The iguana watched us. Perhaps he was even jealous of the telephone.

At last, after, it seemed, more than a dozen abortive telephone calls conducted in Spanish, Quentin got through to someone who said that they were the secretary to the British Consul. Naturally grave and courteous, Quentin enquired whether he might speak to the Consul.

It was the middle of the afternoon.

The reply came from the secretary, that no, Quentin might not speak to the Consul, since the Consul was taking his rest.

It was irresistible not to hope that the Consul was sleeping it off.

In the event, we flew home, happy in the almost certain knowledge that Oliver would be joining us at some point fairly soon. Over the next nine months I doubled in size. This is not a figure of speech. Quentin was gallant about having married someone of ten stone who very shortly became someone of eighteen.

After Oliver’s first Christmas in the hands of his doting but unpractised parents, help arrived in the octogenarian form of Nanny Ramsay. She was the real thing. Her best friend was also a nanny and had, like our nanny, been nanny to three generations of the same family. When they telephoned each other for a chat, they addressed one another as Nanny, as though it was their given name. I do not know Nanny Ramsay’s Christian name. She smoked one cigarette each evening, out of the window, one foot crossed over the other at the ankle and one hand on her narrow hip. The very old-fashioned sort of nannies used to come in two shapes, fat or thin. She was a thin nanny. She wore a white overall, a belt, a hairnet. Michael Foot was leader of the Labour Party at the time and Nanny said of him, ‘Poor Michael Foot, I can’t imagine who his nanny might have been. Look at his hair.’

Nanny was a Scot from Crieff and had retired aged seventy-five. She came out of retirement to do some babies, as favours. She liked to weigh the baby before and after each feed, in proper scales such as a grocer might use, with weights going right down to an eighth of an ounce. Nanny made me keep a notebook to see how Oliver was getting on. It was quite clear that he was thriving. In the scales, he looked much like a person who is always going to hang over the end of things.

There had been but one tricky moment in the haze of delight that surrounded the arrival of Oliver, which was when Quentin’s aunt Camilla visited just before the birth. I had stencilled the cornice of the baby’s room with mermaids and Aunt Mickey, as the family called her, was perfectly content with that. My instinct told me, though we never actually knew from a scan, that the baby would be a boy, and I had purchased what I thought of as a very sensible selection of blue clothes for his arrival, jumpers, jeans, a blanket.

Aunt Mickey instinctively took over the matter of babywear for an impending heir. She took me to the White House, now long gone, where she ordered quires of monogrammed poplin handkerchiefs for the small face to rest upon. Dozens of long white nightgowns with no more than the faintest touch of forget-me-not on the smocking, drifts of shawl made in the Shetland Isles, Egyptian cotton sheets with the discreetest of ‘W’s in the corner, were all were amassed for this most weighty of arrivals. Any other equipment we acquired at the also long-gone Simple Garments of Sloane Street, where it was simply impossible to buy anything synthetic or with animals on it, or anything at all that looked as though it had been confected after 1953. Quentin’s Aunt Philippa Chelsea sent silk bibs. She was the family beauty, lushly voiced, clever, small. She had worked on Jocelyn Stevens’s Queen magazine.

Thank goodness for Aunt Mickey. She had set me on the path of rectitude. And so it was that Oliver and then Clementine were dressed as the kind of children who wore tweed coats with velvet collars and strapped sandals and short pure cotton socks. It is only fair at this stage to say that Clementine complained about this from the age of twelve to the age of twenty-three. She would say, ‘Mummy made me wear smock-dresses and strappy sandals till I was twenty.’ For a long time another line of Clem’s has been that she doesn’t want daughters though this has, by a recent miracle, been lifted during my blindness. The last time we touched on the matter of how she would dress her female children, she said, ‘I’m keeping them in smock-dresses and Mary Janes until they’re thirty!’

Aunt Mickey had worked at Bletchley Park, was widowed young, and lost both her older son and only grandson. For the weeks before my marriage to her nephew, she mothered me at St James’s Palace where the family lived when they were in London. It was at lunch on one of these pre-nuptial days that I learned that one must not cut the nose off a piece of Brie; to do so is called ‘nosing’, as in, ‘My dear, you’ve nosed the Brie’. It was at Aunt Mickey’s table during this astounding week that I looked into the bluest eyes I have ever seen up close, those of Clementine Beit.

Of course she was a Mitford. I fear blue eyes. I like them and I fear them. They freeze the mongrel in me that expects to be whipped.

I must here say something of Aunt Mickey’s brother, Quentin’s father Nol (Oliver) Lymington, my father-in-law. Nol had badly wanted to be a doctor but it was not felt that this was suitable to his station. He was a sweet man, with beautiful legs that he has passed to his son and grandsons. He was frail after a bout of TB and a long stay in Midhurst TB hospital. I am not sure that he received many visitors there, though I know that Mickey was a champion sister to him. He had a wide selection of talents. Towards the end of his shockingly short life, he apprenticed himself to Bill Poon, of Poon’s Chinese restaurant in Soho. Bill Poon was said to be descended from the man who invented the stock cube. Nol came away with a magnificent certificate from Bill Poon, certifying in cursive black ink that ‘Viscount Lee-Min-Tong’ had completed, with distinction, his cookery course. And so he had.

At this point Nol was living with us and I was pregnant: so were many of my friends who lived near us in Hampshire. Nol cut no corners and found every last elephant’s-ear fungus in the stores he haunted in Soho and gave us girls weekly lessons of such detail and panache.

After Chinese food, there was a lull; maybe it was in this lull that he produced my yellow retriever pup Guisachan, dropping her on to my bed as I slept after giving birth to Clementine. The next phase was altogether more esoteric and demanding; Nol became an apprentice chocolatier. He joined the University of the South Bank and learned a tremendous amount about the temperatures at which chocolate is shiny, less shiny, not shiny at all, completely screwed up and so on. He purchased a white overall and he worked in beautiful white gloves. There was nothing he could not do and boxes of chocolates so complex and so pretty that it was impossible to imagine eating them started to appear at family occasions. Nol was the most patient enrober, glosser, crystalliser, ganache-maker and praline-crackist. At this stage in his life he had not yet separated from his third wife. They lived in a house of airy elegance with a parrot named Albert, who had plucked off all the feathers save those on his head, so that Quentin would say he looked oven-ready, and three wire-haired dachshunds named Charlotte, Anne and Emily. The minute precision required by chocolate technology was a challenge to domestic and marital life and it was perhaps a manifestation of their internal schisms when forty-five gallons of enzyme for making soft centres turned up in a drum on the doorstep. Each chocolate requires but one drop.

Nol would have made a good teacher and, in happier times, he could have been an intimate and loving parent and grandparent, had his heart spared him.

The night before our wedding day, I lay in Aunt Mickey’s elder daughter Angela’s maiden bed in St James’s Palace and prayed. I do not remember sleeping though I must have. I remember quantities of indecisive, pleasant February rain falling and the wide view from my window over the sentry box and up St James’s Street. In a box in the cupboard were my white suede shoes, size six, in which I was to walk into my future.

Quentin and I moved to London, renting a house in the Portobello Road, because his bachelor house in London had been set fire to by an arsonist – an episode terrifyingly and more extensively described in Janet Hobhouse’s novel The Furies.

I am incapable of thinking about this with any precision. It occurred around the time of Oliver’s birth. I hardly know about it save through fiction. Quentin had lent his house off Westbourne Grove to Janet when she casually mentioned that she had nowhere to live on a visit to us that snowy winter of Olly’s birth. Janet was living there and lost the manuscript of a book that she was writing on Braque in that fire. Thank God she did not lose her life, though that too was early extinguished by the cancer that drives The Furies into being the stupendous novel it is.

The arsonist had seen Quentin’s car and formed an idea of us for which he evidently did not care. He made a pyre of everything moveable in the house, which was not a great deal, poured petrol over and lit it. Both Quentin and I have, with increasing reason, a deep horror of fire.

During our time in the Portobello Road, Oliver learned to turn somersaults and his sister was conceived. I would not mention this did she not like the idea; it has remained ‘her’ part of London.

While I was expecting Oliver, Quentin himself had been at sea for a good deal of the time, completing his own private circumnavigation on his ketch Ocean Mermaid. Quentin is one of the few people in the world who is entitled to wear the tie of the Association Internationale Amicale des Captains de Longs Cours Cap-Horniers. That is, he has been around Cape Horn, more than once, under sail. To attend the meetings of this society even as an appendage is a privilege. On one occasion, I was lucky enough to see a film made on a full-rigged tea clipper when one of the nonagenarians present had been just a boy holding on for dear life to a spar as the great ship rounded the Horn. No soundtrack, but you read the sails.

Quentin can name the stars and navigate by them. He can find land using dead reckoning. He stopped hunting after his mother’s death and took it up again the day it was made illegal. He has a passion for justice, a tenderness for the underdog, and a mind that works patiently and logically through to the bone of the problem. There is something of Plantagenet Palliser to him. He is quiet, but when he speaks, he has a beautiful voice.

When Clementine was born, Aunt Mickey presided once more like a more worldly angel of maternal lore, and Nanny Ramsay came too. We had a new house to move into, an estate house just beyond the gates of Farleigh House where the school still festered. Clementine had expressively conversational hands and was a very slow eater. She decided not to breastfeed and very early conquered her larger brother, who referred to her as ‘Birdy’ until her birth and was her subject in love as soon as he saw her. He would stand with his feet tucked into the bars of her cot and loom over her, shedding a shadow that was bright orange at the top where the sun fell upon it. They were, and are, each other’s stalwart best defender.

After the birth of Clem, the health visitor suggested that I might like to get out of the house a bit and do some A levels with a view to gaining some qualifications – and perhaps some other ‘interest’. I was reading avidly, though that is not invariably deleterious to the raising of happy and balanced children, and both children seemed to be flourishing. I was one of the first people to read Midnight’s Children. As well as the seethe of the book, I liked the look of the thin, modest, exhausted author. Shrewd of me, if not precisely prophetic.

Things between Quentin and me had shifted and held us apart at an undeclared pitch of difficulty. We could not find the words with which to row our way to safety, then found the wrong ones. Not for the first time I lit upon escape as a solution. My father wrote me a, for him, unusually direct letter of concern. It suggested that although powerfully drawn by temperament to Italy, he had come to place a higher value on the aesthetics of the Dutch School. He loved Quentin.

I left Farleigh. I went to stay with my friend Rosa Beddington in her tiny house in Oxford. The telephone rang. It was Lucinda Wallop, Quentin’s sister. She said, ‘Daddy’s dead.’ I said, ‘No, he can’t be.’ He was only sixty-one and Quentin had just found a home for him close to us on an island on the River Test. He was a loveable, unrealised man.

I visited estate agents. I am not at all sure how lucid I was. One estate agent assured me that very few rental houses accepted children, most particularly not one house I liked the sound of that lay deep in rural Buckinghamshire. ‘No Children’, I read. There were no pictures of the property.

Very uncharacteristically, I found myself driving down a half-hidden road signed to Wotton Underwood. I could park my little car because there was a large gravelly yard to the side of what seemed to be an architectural hallucination, a golden pink central house flanked by lantern-shaped pavilions, behind delicate wrought-iron, golden-berried gates. It was a sleeping beauty. I looked to my right and saw that there was a gate leading to a wishing well on a wide lawn that ended in a ha-ha and beyond that at least one lake. I rang a doorbell at the side of the house. A funny bracket, as though for a pub sign the size of an equestrian portrait, stuck out of the side that faced where the cars were parked. It was high summer. I realised that this bracket must be for swinging in enormous paintings, pianos, furniture through the great windows of the house. The door was answered by a woman with my maternal grandmother’s very voice. She took one look at me. I was not a pretty sight, fat, wretched, scared, uprooted, unaware that alcohol would never make anything better. The witch who opened the door, for a white witch she was, said, ‘My child, you will live here. And you will bring your children.’

This phenomenon was Mrs Elaine Brunner, who, going one day to a garden clearance sale in the 1950s had seen the house to which that garden was attached. The house was due for demolition, having in its last usage been a school for delinquent boys. She had on that day a powerful instinct that underneath the Edwardian modernisations by Sir Reginald Blomfield there still lurked a Soane house. It had been built for the dukes of Buckingham and Chandos as a companion house to Stowe.

She saved it, buying it for a sum, I think, close to £5,000. She was, right up till her death, one of the most compelling, sexy yet maternal and grand-maternal women I’ve ever known. She was one of the beloved monsters of my life and she worked untiringly for that extraordinary palace she saved.

My first night at Wotton, I slept in a slightly-adapted-for-lodgers ducal apartment. The telephone went and it was Quentin. It seemed to be ridiculous to be separated from someone whom one so wished to console. I asked him whether he wanted me to attend his father’s funeral and he said, ‘It depends on whether you cared for him or not.’ Of course I went.

And so we parted, as though our lives were happening to other people. We held hands in court and there seemed no question but that the children, on account of their situation, must stay at Farleigh. It was more unusual then, and my sense that this was the right decision was not one that I could ever make clear to any but the most intimate of my friends.

People have tackled me about this, thinking it unnatural or weak, but it laid between the children’s father and myself a small island of trust amid the perilous currents of divorce. It was the children who mattered. Whether or not it was right for the children can only be gauged by them. I wanted Quentin to trust me and knew that the next thing we had to build was a safe place for our children.

Mrs Brunner it was who insisted that we all, including Quentin, have Christmas together at Wotton. On the years when the children were with me at Christmas after that, Quentin went and worked for the homeless at Crisis at Christmas. I received a letter from Aunt Mickey that told me among many other things I had lost ‘a place in the world’.