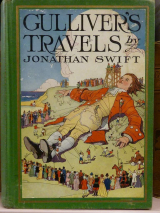

Текст книги "Путешествия Гулливера (Gulliver's Travels)"

Автор книги: Джонатан Свифт

Жанры:

Зарубежная классика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 33 (всего у книги 39 страниц)

«In the trial of persons accused for crimes against the state, the method is much more short and commendable: the judge first sends to sound the disposition of those in power, after which he can easily hang or save a criminal, strictly preserving all due forms of law.»

Судопроизводство над лицами, обвиняемыми в государственных преступлениях, отличается несравненно большей быстротой, и метод его гораздо похвальнее: судья первым делом осведомляется о расположении власть имущих, после чего без труда приговаривает обвиняемого к повешению или оправдывает, строго соблюдая при этом букву закона.

Here my master interposing, said, «it was a pity, that creatures endowed with such prodigious abilities of mind, as these lawyers, by the description I gave of them, must certainly be, were not rather encouraged to be instructors of others in wisdom and knowledge.»

Тут мой хозяин прервал меня, выразив сожаление, что существа, одаренные такими поразительными способностями, как эти судейские, если судить по моему описанию, не поощряются к наставлению других в мудрости и добродетели.

In answer to which I assured his honour, «that in all points out of their own trade, they were usually the most ignorant and stupid generation among us, the most despicable in common conversation, avowed enemies to all knowledge and learning, and equally disposed to pervert the general reason of mankind in every other subject of discourse as in that of their own profession.»

В ответ на это я уверил его милость, что во всем, не имеющем отношения к их профессии, они являются обыкновенно самыми невежественными и глупыми из всех нас, неспособными вести самый простой разговор, заклятыми врагами всякого знания и всякой науки, так же склонными извращать здравый человеческий смысл во всех других областях, как они извращают его в своей профессии.

CHAPTER VI.

ГЛАВА VI

A continuation of the state of England under Queen Anne.

Продолжение описания Англии[146].

The character of a first minister of state in European courts.

Характеристика первого или главного министра при европейских дворах

My master was yet wholly at a loss to understand what motives could incite this race of lawyers to perplex, disquiet, and weary themselves, and engage in a confederacy of injustice, merely for the sake of injuring their fellow-animals; neither could he comprehend what I meant in saying, they did it for hire.

Мой хозяин все же был совершенно не способен понять, что заставляет это племя законников тревожиться, беспокоиться, утруждать себя и вступать в союз с несправедливостью только ради причинения вреда своим ближним; он не мог также постичь, что я разумею, говоря, что они делают это за наемную плату.

Whereupon I was at much pains to describe to him the use of money, the materials it was made of, and the value of the metals; "that when a Yahoo had got a great store of this precious substance, he was able to purchase whatever he had a mind to; the finest clothing, the noblest houses, great tracts of land, the most costly meats and drinks, and have his choice of the most beautiful females.

В ответ на это мне пришлось с большими затруднениями описать ему употребление денег, материал, из которого они изготовляются, и цену благородных металлов; я сказал ему, что когда еху собирает большой запас этого драгоценного вещества, то он может приобрести все, что ему вздумается: красивые платья, великолепные дома, большие пространства земли, самые дорогие яства и напитки; ему открыт выбор самых красивых самок.

Therefore since money alone was able to perform all these feats, our Yahoos thought they could never have enough of it to spend, or to save, as they found themselves inclined, from their natural bent either to profusion or avarice; that the rich man enjoyed the fruit of the poor man's labour, and the latter were a thousand to one in proportion to the former; that the bulk of our people were forced to live miserably, by labouring every day for small wages, to make a few live plentifully."

И так как одни только деньги способны доставить все эти штуки, то нашим еху все кажется, что денег у них недостаточно на расходы или на сбережения, в зависимости от того, к чему они больше предрасположены: к мотовству или к скупости. Я сказал также, что богатые пожинают плоды работы бедных, которых приходится по тысяче на одного богача, и что громадное большинство нашего народа принуждено влачить жалкое существование, работая изо дня в день за скудную плату, чтобы меньшинство могло жить в изобилии.

I enlarged myself much on these, and many other particulars to the same purpose; but his honour was still to seek; for he went upon a supposition, that all animals had a title to their share in the productions of the earth, and especially those who presided over the rest.

Я подробно остановился на этом вопросе и разных связанных с ним частностях, но его милость плохо схватывал мою мысль, ибо он исходил из положения, что все животные имеют право на свою долю земных плодов, особенно те, которые господствуют над остальными.

Therefore he desired I would let him know, «what these costly meats were, and how any of us happened to want them?»

Поэтому он выразил желание знать, каковы же эти дорогие яства и почему некоторые из нас нуждаются в них.

Whereupon I enumerated as many sorts as came into my head, with the various methods of dressing them, which could not be done without sending vessels by sea to every part of the world, as well for liquors to drink as for sauces and innumerable other conveniences.

Тогда я перечислил все самые изысканные кушанья, какие я только мог припомнить, и описал различные способы их приготовления, заметив, что за приправами к ним, за напитками и бесчисленными пряностями приходится посылать корабли за море во все страны света.

I assured him «that this whole globe of earth must be at least three times gone round before one of our better female Yahoos could get her breakfast, or a cup to put it in.»

Я сказал ему, что нужно, по крайней мере, трижды объехать весь земной шар, прежде чем удастся достать провизию для завтрака какой-нибудь знатной самки наших еху или чашку, в которой он должен быть подан.

He said "that must needs be a miserable country which cannot furnish food for its own inhabitants.

Бедна же, однако, страна, – сказал мой собеседник, – которая не может прокормить своего населения!

But what he chiefly wondered at was, how such vast tracts of ground as I described should be wholly without fresh water, and the people put to the necessity of sending over the sea for drink."

Но особенно его поразило то, что описанные мной обширные территории совершенно лишены пресной воды и население их вынуждено посылать в заморские земли за питьем.

I replied "that England (the dear place of my nativity) was computed to produce three times the quantity of food more than its inhabitants are able to consume, as well as liquors extracted from grain, or pressed out of the fruit of certain trees, which made excellent drink, and the same proportion in every other convenience of life.

Я ответил ему на это, что Англия (дорогая моя родина), по самому скромному подсчету, производит разного рода съестных припасов в три раза больше, чем способно потребить ее население, а что касается питья, то из зерна некоторых злаков и из плодов некоторых растений мы извлекаем или выжимаем сок и получаем, таким образом, превосходные напитки; в такой же пропорции у нас производится все вообще необходимое для жизни.

But, in order to feed the luxury and intemperance of the males, and the vanity of the females, we sent away the greatest part of our necessary things to other countries, whence, in return, we brought the materials of diseases, folly, and vice, to spend among ourselves.

Но для утоления сластолюбия и неумеренности самцов и суетности самок мы посылаем большую часть необходимых нам предметов в другие страны, откуда взамен вывозим материалы для питания наших болезней, пороков и прихотей.

Hence it follows of necessity, that vast numbers of our people are compelled to seek their livelihood by begging, robbing, stealing, cheating, pimping, flattering, suborning, forswearing, forging, gaming, lying, fawning, hectoring, voting, scribbling, star-gazing, poisoning, whoring, canting, libelling, freethinking, and the like occupations:" every one of which terms I was at much pains to make him understand.

Отсюда неизбежно следует, что огромное количество моих соотечественников вынуждено добывать себе пропитание нищенством, грабежом, воровством, мошенничеством, сводничеством, клятвопреступлением, лестью, подкупами, подлогами, игрой, ложью, холопством, бахвальством, торговлей избирательными голосами, бумагомаранием, звездочетством, отравлением, развратом, ханжеством, клеветой, вольнодумством и тому подобными занятиями; читатель может себе представить, сколько труда мне понадобилось, чтобы растолковать гуигнгнму каждое из этих слов[147].

"That wine was not imported among us from foreign countries to supply the want of water or other drinks, but because it was a sort of liquid which made us merry by putting us out of our senses, diverted all melancholy thoughts, begat wild extravagant imaginations in the brain, raised our hopes and banished our fears, suspended every office of reason for a time, and deprived us of the use of our limbs, till we fell into a profound sleep; although it must be confessed, that we always awaked sick and dispirited; and that the use of this liquor filled us with diseases which made our lives uncomfortable and short.

Я объяснил ему, что вино, привозимое к нам из чужих стран, служит не для восполнения недостатка в воде и в других напитках, но влага эта веселит нас, одурманивает, рассеивает грустные мысли, наполняет мозг фантастическими образами, убаюкивает несбыточными надеждами, прогоняет страх, приостанавливает на некоторое время деятельность разума, лишает нас способности управлять движениями нашего тела и в заключение погружает в глубокий сон; правда, нужно признать, что от такого сна мы просыпаемся всегда больными и удрученными и что употребление этой влаги рождает в нас всякие недуги, делает нашу жизнь несчастной и сокращает ее.

"But beside all this, the bulk of our people supported themselves by furnishing the necessities or conveniences of life to the rich and to each other.

Кроме все этого, большинство населения добывает у нас средства к существованию снабжением богачей и вообще друг друга предметами первой необходимости и роскоши.

For instance, when I am at home, and dressed as I ought to be, I carry on my body the workmanship of a hundred tradesmen; the building and furniture of my house employ as many more, and five times the number to adorn my wife."

Например, когда я нахожусь у себя дома и одеваюсь как мне полагается, я ношу на своем теле работу сотни ремесленников; постройка и обстановка моего дома требуют еще большего количества рабочих, а чтобы нарядить мою жену, нужно увеличить это число еще в пять раз.

I was going on to tell him of another sort of people, who get their livelihood by attending the sick, having, upon some occasions, informed his honour that many of my crew had died of diseases. But here it was with the utmost difficulty that I brought him to apprehend what I meant.

Я собрался было рассказать ему еще об одном разряде людей, добывающих себе средства к жизни уходом за больными, ибо не раз уже упоминал его милости, что много матросов на моем корабле погибло от болезней; но тут мне пришлось затратить много времени на то, чтобы растолковать ему мои намерения.

«He could easily conceive, that a Houyhnhnm, grew weak and heavy a few days before his death, or by some accident might hurt a limb; but that nature, who works all things to perfection, should suffer any pains to breed in our bodies, he thought impossible, and desired to know the reason of so unaccountable an evil.»

Для него было вполне понятно, что каждый гуигнгнм слабеет и отяжелевает за несколько дней до смерти или может случайно поранить себя. Но он не мог допустить, чтобы природа, все произведения которой совершенны, способна была взращивать в нашем теле болезни, и пожелал узнать причину этого непостижимого бедствия.

I told him "we fed on a thousand things which operated contrary to each other; that we ate when we were not hungry, and drank without the provocation of thirst; that we sat whole nights drinking strong liquors, without eating a bit, which disposed us to sloth, inflamed our bodies, and precipitated or prevented digestion; that prostitute female Yahoos acquired a certain malady, which bred rottenness in the bones of those who fell into their embraces; that this, and many other diseases, were propagated from father to son; so that great numbers came into the world with complicated maladies upon them; that it would be endless to give him a catalogue of all diseases incident to human bodies, for they would not be fewer than five or six hundred, spread over every limb and joint-in short, every part, external and intestine, having diseases appropriated to itself.

Я рассказал ему, что мы употребляем в пищу тысячу различных веществ, которые часто оказывают на наш организм самые противоположные действия; что мы едим, когда мы не голодны, и пьем, не чувствуя никакой жажды; что целые ночи напролет мы поглощаем крепкие напитки и ничего при этом не едим, что располагает нас к лени, воспаляет наши внутренности, расстраивает желудок или препятствует пищеварению; что занимающиеся проституцией самки еху наживают особую болезнь, от которой гниют кости, и заражают этой болезнью каждого, кто попадает в их объятия; что эта болезнь, как и многие другие, передается от отца к сыну, так что многие из нас уже при рождении на свет носят в себе зачатки недугов; что понадобилось бы слишком много времени для перечисления всех болезней, которым подвержено человеческое тело, так как не менее пяти– или шестисот их поражают каждый его член и сустав; словом, всякая часть нашего тела, как внешняя, так и внутренняя, подвержена множеству свойственных ей болезней.

To remedy which, there was a sort of people bred up among us in the profession, or pretence, of curing the sick.

Для борьбы с этим злом у нас существует особый род людей, обученных искусству лечить или морочить больных.

And because I had some skill in the faculty, I would, in gratitude to his honour, let him know the whole mystery and method by which they proceed. "Their fundamental is, that all diseases arise from repletion; whence they conclude, that a great evacuation of the body is necessary, either through the natural passage or upwards at the mouth. Their next business is from herbs, minerals, gums, oils, shells, salts, juices, sea-weed, excrements, barks of trees, serpents, toads, frogs, spiders, dead men's flesh and bones, birds, beasts, and fishes, to form a composition, for smell and taste, the most abominable, nauseous, and detestable, they can possibly contrive, which the stomach immediately rejects with loathing, and this they call a vomit; or else, from the same store-house, with some other poisonous additions, they command us to take in at the orifice above or below (just as the physician then happens to be disposed) a medicine equally annoying and disgustful to the bowels; which, relaxing the belly, drives down all before it; and this they call a purge, or a clyster. For nature (as the physicians allege) having intended the superior anterior orifice only for the intromission of solids and liquids, and the inferior posterior for ejection, these artists ingeniously considering that in all diseases nature is forced out of her seat, therefore, to replace her in it, the body must be treated in a manner directly contrary, by interchanging the use of each orifice; forcing solids and liquids in at the anus, and making evacuations at the mouth.

И так как я обладал некоторыми сведениями в этом искусстве, то в знак благодарности к его милости изъявил готовность посвятить его в тайны и методы их действий.

"But, besides real diseases, we are subject to many that are only imaginary, for which the physicians have invented imaginary cures; these have their several names, and so have the drugs that are proper for them; and with these our female Yahoos are always infested.

Но, кроме действительных болезней, мы подвержены множеству мнимых, против которых врачи изобрели мнимое лечение; эти болезни имеют свои названия и соответствующие лекарства; ими всегда страдают самки наших еху.

"One great excellency in this tribe, is their skill at prognostics, wherein they seldom fail; their predictions in real diseases, when they rise to any degree of malignity, generally portending death, which is always in their power, when recovery is not: and therefore, upon any unexpected signs of amendment, after they have pronounced their sentence, rather than be accused as false prophets, they know how to approve their sagacity to the world, by a seasonable dose.

Особенно отличается это племя в искусстве прогноза; тут они редко совершают промах; действительно, в случае настоящей болезни, более или менее злокачественной, медики обыкновенно предсказывают смерть, которая всегда в их власти, между тем как излечение от них не зависит; поэтому при неожиданных признаках улучшения, после того как ими уже был произнесен приговор, они, не желая прослыть лжепророками, умеют доказать свою мудрость своевременно данной дозой лекарства.

«They are likewise of special use to husbands and wives who are grown weary of their mates; to eldest sons, to great ministers of state, and often to princes.»

Равным образом они бывают весьма полезны мужьям и женам, если те надоели друг другу, старшим сыновьям, министрам и часто государям.

I had formerly, upon occasion, discoursed with my master upon the nature of government in general, and particularly of our own excellent constitution, deservedly the wonder and envy of the whole world.

Мне уже раньше приходилось беседовать с моим хозяином о природе правительства вообще и в частности о нашей превосходной конституции, вызывающей заслуженное удивление и зависть всего света.

But having here accidentally mentioned a minister of state, he commanded me, some time after, to inform him, «what species of Yahoo I particularly meant by that appellation.»

Но когда я случайно при этом упомянул государственного министра, то мой хозяин спустя некоторое время попросил меня объяснить ему, какую именно разновидность еху обозначаю я этим словом.

I told him, "that a first or chief minister of state, who was the person I intended to describe, was the creature wholly exempt from joy and grief, love and hatred, pity and anger; at least, makes use of no other passions, but a violent desire of wealth, power, and titles; that he applies his words to all uses, except to the indication of his mind; that he never tells a truth but with an intent that you should take it for a lie; nor a lie, but with a design that you should take it for a truth; that those he speaks worst of behind their backs are in the surest way of preferment; and whenever he begins to praise you to others, or to yourself, you are from that day forlorn.

Я ответил ему, что первый или главный государственный министр[148], особу которого я намереваюсь описать, является существом, совершенно не подверженным радости и горю, любви и ненависти, жалости и гневу; по крайней мере, он не проявляет никаких страстей, кроме неистовой жажды богатства, власти и титулов; что он пользуется словами для самых различных целей, но только не для выражения своих мыслей; что он никогда не говорит правды иначе как с намерением, чтобы ее приняли за ложь, и лжет только в тех случаях, когда хочет выдать свою ложь за правду; что люди, о которых он дурно отзывается за глаза, могут быть уверены, что они находятся на пути к почестям; если же он начинает хвалить вас перед другими или в глаза, с того самого дня вы человек пропащий.

The worst mark you can receive is a promise, especially when it is confirmed with an oath; after which, every wise man retires, and gives over all hopes.

Наихудшим предзнаменованием для вас бывает обещание, особенно когда оно подтверждается клятвой; после этого каждый благоразумный человек удаляется и оставляет всякую надежду.

"There are three methods, by which a man may rise to be chief minister.

Есть три способа, при помощи которых можно достигнуть поста главного министра.

The first is, by knowing how, with prudence, to dispose of a wife, a daughter, or a sister; the second, by betraying or undermining his predecessor; and the third is, by a furious zeal, in public assemblies, against the corruption's of the court.

Первый способ – уменье благоразумно распорядиться женой, дочерью или сестрой; второй – предательство своего предшественника или подкоп под него; и, наконец, третий -яростное обличение в общественных собраниях испорченности двора.

But a wise prince would rather choose to employ those who practise the last of these methods; because such zealots prove always the most obsequious and subservient to the will and passions of their master.

Однако мудрый государь обыкновенно отдает предпочтение тем, кто применяет последний способ, ибо эти фанатики всегда с наибольшим раболепием будут потакать прихотям и страстям своего господина.

That these ministers, having all employments at their disposal, preserve themselves in power, by bribing the majority of a senate or great council; and at last, by an expedient, called an act of indemnity" (whereof I described the nature to him), "they secure themselves from after-reckonings, and retire from the public laden with the spoils of the nation.

Достигнув власти, министр, в распоряжении которого все должности, укрепляет свое положение путем подкупа большинства сенаторов или членов большого совета; в заключение, оградив себя от всякой ответственности особым актом, называемым амнистией (я изложил его милости сущность этого акта), он удаляется от общественной деятельности, отягченный награбленным у народа богатством.

"The palace of a chief minister is a seminary to breed up others in his own trade: the pages, lackeys, and porters, by imitating their master, become ministers of state in their several districts, and learn to excel in the three principal ingredients, of insolence, lying, and bribery.

Дворец первого министра служит питомником для выращивания других подобных ему людей: пажи, лакеи, швейцары, подражая своему господину, становятся такими же министрами в своей сфере и в совершенстве изучают три главных составных части его искусства: наглость, ложь и подкуп.

Accordingly, they have a subaltern court paid to them by persons of the best rank; and sometimes by the force of dexterity and impudence, arrive, through several gradations, to be successors to their lord.

Вследствие этого у каждого из них есть свой маленький двор, образуемый людьми высшего круга. Подчас благодаря ловкости и бесстыдству им удается, поднимаясь со ступеньки на ступеньку, стать преемниками своего господина.

«He is usually governed by a decayed wench, or favourite footman, who are the tunnels through which all graces are conveyed, and may properly be called, in the last resort, the governors of the kingdom.»

Первым министром управляет обыкновенно какая-нибудь старая распутница или лакей-фаворит, они являются каналами, по которым разливаются все милости министра, и по справедливости могут быть названы в последнем счете правителями государства.

One day, in discourse, my master, having heard me mention the nobility of my country, was pleased to make me a compliment which I could not pretend to deserve: «that he was sure I must have been born of some noble family, because I far exceeded in shape, colour, and cleanliness, all the Yahoos of his nation, although I seemed to fail in strength and agility, which must be imputed to my different way of living from those other brutes; and besides I was not only endowed with the faculty of speech, but likewise with some rudiments of reason, to a degree that, with all his acquaintance, I passed for a prodigy.»

Однажды, услышав мое упоминание о знати нашей страны, хозяин удостоил меня комплиментом, которого я совсем не заслужил. Он сказал, что я, наверное, родился в благородной семье, так как по сложению, цвету кожи и чистоплотности я значительно превосхожу всех еху его родины, хотя, по-видимому, и уступаю последним в силе и ловкости, что, по его мнению, обусловлено моим образом жизни, отличающимся от образа жизни этих животных; кроме того, я не только одарен способностью речи, но также некоторыми зачатками разума в такой степени, что все его знакомые почитают меня за чудо.

He made me observe, «that among the Houyhnhnms, the white, the sorrel, and the iron-gray, were not so exactly shaped as the bay, the dapple-gray, and the black; nor born with equal talents of mind, or a capacity to improve them; and therefore continued always in the condition of servants, without ever aspiring to match out of their own race, which in that country would be reckoned monstrous and unnatural.»

Он обратил мое внимание на то, что среди гуигнгнмов белые, гнедые и темно-серые хуже сложены, чем серые в яблоках, караковые и вороные; они не обладают такими природными дарованиями и в меньшей степени поддаются развитию; поэтому всю свою жизнь они остаются в положении слуг, даже и не мечтая о лучшей участи, ибо все их притязания были бы признаны здесь противоестественными и чудовищными.

I made his honour my most humble acknowledgments for the good opinion he was pleased to conceive of me, but assured him at the same time, "that my birth was of the lower sort, having been born of plain honest parents, who were just able to give me a tolerable education; that nobility, among us, was altogether a different thing from the idea he had of it; that our young noblemen are bred from their childhood in idleness and luxury; that, as soon as years will permit, they consume their vigour, and contract odious diseases among lewd females; and when their fortunes are almost ruined, they marry some woman of mean birth, disagreeable person, and unsound constitution (merely for the sake of money), whom they hate and despise. That the productions of such marriages are generally scrofulous, rickety, or deformed children; by which means the family seldom continues above three generations, unless the wife takes care to provide a healthy father, among her neighbours or domestics, in order to improve and continue the breed. That a weak diseased body, a meagre countenance, and sallow complexion, are the true marks of noble blood; and a healthy robust appearance is so disgraceful in a man of quality, that the world concludes his real father to have been a groom or a coachman.

Я выразил его милости мою нижайшую благодарность за доброе мнение, которое ему угодно было составить обо мне, но уверил его в то же время, что происхождение мое очень невысокое, так как мои родители были скромные честные люди, которые едва имели возможность дать мне сносное образование; я сказал ему, что наша знать совсем не похожа на то представление, какое он составил о ней; что молодые ее представители с самого детства воспитываются в праздности и роскоши и, как только им позволяет возраст, сжигают свои силы в обществе распутных женщин, от которых заражаются дурными болезнями; промотав, таким образом, почти все свое состояние, они женятся ради денег на женщинах низкого происхождения, не отличающихся ни красотой, ни здоровьем, которых они ненавидят и презирают; что плодом таких браков обыкновенно являются золотушные, рахитичные или уродливые дети, вследствие чего знатные фамилии редко сохраняются долее трех поколений, разве только жены предусмотрительно выбирают среди соседей и прислуги здоровых отцов в целях улучшения и продолжения рода; что слабое болезненное тело, худоба и землистый цвет лица служат верными признаками благородной крови, здоровое и крепкое сложение считается даже бесчестием для человека знатного, ибо при виде такого здоровяка все тотчас заключают, что его настоящим отцом был конюх или кучер.

The imperfections of his mind run parallel with those of his body, being a composition of spleen, dullness, ignorance, caprice, sensuality, and pride.

Недостатки физические находятся в полном соответствии с недостатками умственными и нравственными, так что люди эти представляют собой смесь хандры, тупоумия, невежества, самодурства, чувственности и спеси.

«Without the consent of this illustrious body, no law can be enacted, repealed, or altered: and these nobles have likewise the decision of all our possessions, without appeal.» [514]

И вот без согласия этого блестящего класса не может быть издан, отменен или изменен ни один закон; эти же люди безапелляционно решают все наши имущественные отношения[149].

CHAPTER VII.

ГЛАВА VII

The author's great love of his native country.

Великая любовь автора к своей родной стране.

His master's observations upon the constitution and administration of England, as described by the author, with parallel cases and comparisons.

Замечания хозяина относительно описанных автором английской конституции и английского правления, с приведением параллелей и сравнений.

His master's observations upon human nature.

Наблюдения хозяина над человеческой природой

The reader may be disposed to wonder how I could prevail on myself to give so free a representation of my own species, among a race of mortals who are already too apt to conceive the vilest opinion of humankind, from that entire congruity between me and their Yahoos.

Читатель будет, пожалуй, удивлен, каким образом я мог решиться изобразить наше племя в столь неприкрытом виде перед породой существ, и без того очень склонявшихся к самому неблагоприятному мнению о человеческом роде благодаря моему полному сходству с тамошними еху.

But I must freely confess, that the many virtues of those excellent quadrupeds, placed in opposite view to human corruptions, had so far opened my eyes and enlarged my understanding, that I began to view the actions and passions of man in a very different light, and to think the honour of my own kind not worth managing; which, besides, it was impossible for me to do, before a person of so acute a judgment as my master, who daily convinced me of a thousand faults in myself, whereof I had not the least perception before, and which, with us, would never be numbered even among human infirmities.