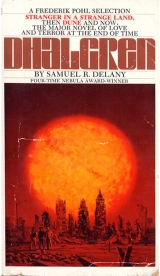

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

III House of the Ax

BEGINNING IN THIS TONE is, for us, a little odd, but such news stands out, to your editor’s mind, as the impressive occurrence in our eccentric history. Ernest Newboy, the most notable English-language poet to emerge from Oceania, was born in Auckland in 1916. Sent to school in England, at twenty-one (he tells us) he came back to New Zealand and Australia to teach for six years, then returned to Europe to work and travel.

Mr. Newboy has been three times short-listed for the Nobel Prize, which, if he receives it, will make him one in a line of outstanding figures in the twin fields of diplomacy and letters which includes Asturias, St-John Perse, and Seferis. As a citizen of a comparatively neutral country, he has been visiting the United States at an invitation to sit on the United Nations Cultural Committee which has just adjourned.

Ernest Newboy is also the author of a handful of short stories and novellas, collected and published under the title Stones (Vintage Paperback, 387 pp., $2.95), including the often anthologized long story, “The Monument,” a disturbing and symbolic tale of the psychological and spiritual dissolution of a disaffected Australian intellectual who comes to live in a war-ravaged German town. Mr. Newboy has told us that, though his popular reputation rests on that slim volume of incisive fiction (your editor’s evaluation), he considers them essentially experiments of the three years following the close of the War when he passed through a period of disillusionment with his first literary commitment, poetry. If nothing else, the popularity of Stones and “The Monument” turned attention to the three volumes of poems published in the thirties and forties, brought together in Collected Poetry 1950 (available in Great Britain from Faber and Faber). To repeat something of a catch-phrase that has been echoed by various critics: While writers about him caught the despair of the period surrounding the War, Newboy, more than any other, fixed it in such light that one can lucidly see in it the genesis of so much of the current crisis. From his early twenties, through today, Newboy has produced occasional, literary, and philosophical essays to fill several volumes. They are characterized by a precise and courageous vision. In 1969 he published the book-length poem Pilgrimage, abstruse, surreal, often surprisingly humorous, and, for all its apparent irreverence, a profoundly religious work. After several more volumes of essays, in 1975 the comparatively brief collection of shorter poems written in the thirty-odd years since the War, Rictus, appeared.

A quiet, retiring, scholarly man, Newboy has traveled for most of his life through Europe, North Africa, and the East. His work is studded with images from the Maori and the many cultures he has been exposed to and explored, with his particular personal insight.

Newboy arrived in Bellona yesterday morning and is indefinite about the length of his stay. His comment to us when asked about his visit was, after a reticent smile: “Well, a week ago I wasn’t intending to come here at all. But I suppose I’m happy I did.”

We are honored that a man with such achievement in English letters and a figure of such world admiration should…

“What are you doing?” she mumbled, turning from his side.

“Reading the paper.” Grass creased his elbows. He had wiggled free of the blanket as far as his hips.

“Did it come out yet?” She raised her head in a haze of slept-in hair. “It isn’t that late…?”

“Yesterday’s.”

She dropped her head back. “That’s the trouble with sleeping out. You can’t do it past five o’clock in the morning.”

“I bet it’s eight.” He spread the wrinkled page bottom.

“What—” opened her eyes and squinted—“you reading about?”

“Newboy. That poet.”

“Oh, yeah.”

“I met him.”

“You did?” She raised her head again, then twisted, tearing blankets from his leg. “When?”

“Up at Calkins’.”

She pulled up beside him, hot shoulder on his. Under the headline NEW BOY IN TOWN! was a picture of a thin white-haired man in a dark suit with a narrow tie, sitting in a chair, legs crossed, looking as though there were too much light in his face. “You saw him?”

“When I got beat up. He came out and helped me. From New Zealand; it sounded like he had some sort of accent.”

“Told you Bellona was a small town.” She looked at the picture. “Hey, how come you didn’t get inside then?”

“Somebody else was with him who raised a stink. A spade. Fenster. He’s the civil rights guy or something?”

She blinked at him. “You really are out meeting everybody.”

“I wish I hadn’t met Fenster.” He snorted.

“I told you about Calkins’ country weekends. Only he has them seven days a week.”

“How does he get time to write for the paper?”

She shrugged. “But he does. Or gets somebody to do it for him.” She sat up to paw the blankets. “Where did my shirt go?”

He liked her quivering breasts.

“It’s under there.” He looked back at the paper, but did not read. “I wonder if he’s ever had George up there?”

“Maybe. He did that interview thing.”

“Mmmm.”

Lanya dropped back to the grass. “Hell. It isn’t past five o’clock in the morning. You know damn well it isn’t.”

“Eight,” he decided. “Feels like eight-thirty,” and followed her glance up to the close smoke over the leaves. He looked down again, and she was smiling, reaching for his head, pulling him, rocking, by the ears, down: He laughed on her skin. “Come on! Let me go!”

She hissed, slow. “Oh, I can for a while,” caught her breath when his head raised, then whispered, “sleep…” and put her forearm over her face. He lost himself in the small bronze curls under her arm, and only loosened his eyes at faint barking.

He sat, puzzled. Barking pricked the distance. He blinked, and in the bright dark of his lids, oily motes exploded. Puzzlement became surprise, and he stood.

Blankets fell down his legs.

He stepped on the grass, naked in the mist.

Far away a dog romped and turned in the gap between hills. A woman followed.

Anticipatory wonder caught in the dizzy fatigue of morning and sudden standing.

The chain around his body had left red marks on the underside of his forearms and the front of his belly where he’d leaned.

He got on his pants.

Shirt open over tears of jewels, he walked down the slope. Once he looked back at Lanya. She had rolled over on her stomach, face in the grass.

He walked toward where the woman (the redhead, from the bar) followed behind Muriel.

He fastened one shirt button before she saw him. She turned on sensible walking shoes and said, “Ah, hello. Good morning.”

Around her neck, the jewels were a cluttered column of light.

“Hi.” He pulled his toes in in the grass, shy. “I saw your dog last night, at that bar.”

“Oh, yes. And I saw you. You look a little better this morning. Got yourself cleaned up. Slept in the park?”

“Yeah.”

Where candlelight had made her seem a big-boned whore, smoke-light and a brown suit took all the meretricious from her rough, red hair and made her an elementary-school assistant principal.

“You walk your dog here?”

An assistant principal with a gaudy necklace.

“Every morning, bright and early…um, I’m going to the exit now.”

“Oh,” and then decided her tentativeness was invitation.

They walked, and Muriel ran up to sniff his hand, nip at it.

“Cut that out,” she demanded. “Be a good dog.”

Muriel barked once, then trotted ahead.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“Ah!” she repeated. “I’m Madame Brown. Muriel went over and barked at you last night, didn’t she? Well, she doesn’t mean anything by it.”

“Yeah. I guess not.”

“About all you need now is a comb—” she frowned at him—“and a towel, and you will be back in shape.” She released her shrill and astounding laughter. “There’s a public john over there where I always see the people from the commune going to wash up.” Then she looked at him seriously. “You’re not with the commune there, are you?”

“No.”

“Do you want a job?”

“Huh?”

“At least you’re not a long-hair,” she said. “Not very long, anyway. I asked you if you wanted a job.”

“I wear sandals,” he said, “when I put anything on my feet at all.”

“That’s all right. Oh, heavens, I don’t care! I’m just thinking of the people you’d be working for.”

“What kind of work is it? “

“Mainly cleaning up, or cleaning out I suppose. You are interested, aren’t you? They’ll pay five dollars an hour, and those aren’t the sort of wages you can sneeze at in Bellona right through here.”

“Sure I’m interested!” He swallowed in surprise. “Where is it?”

They approached twin lions. Madame Brown put her hands behind her back. Muriel brushed the hem of her skirt. The glut of chain and glass could catch no glitter in this light. “It’s a family. Do you know where the Labry Apartments are?” To his shaking head: “I guess you haven’t been here very long. This family, now, they’re nice, decent people. And they’ve been very helpful to me. I used to have my office over there. You know there was a bit of confusion at the beginning, a bit of damage.”

“I heard about some of it.”

“A lot of vandalism. Now that it’s settled down some, they asked me if I knew some young man who would help them. You mustn’t take the long-hair thing seriously. Just clean yourself up a little—though it probably isn’t going to be very clean work. The Richards are fine people. They’ve just had a lot of trouble. We all have. Mrs. Richards gets easily upset by…anything strange. Mr. Richards perhaps goes a little too far in trying to protect her. They’ve got three very nice children.”

He pushed his hair from his forehead. “I don’t think it’s going to grow too much in the next couple of days.”

“There! You do understand!”

“It’s a good job?”

“Oh, it is. It certainly is.” She stopped at the lions as though they marked some far more important boundary. “That’s the Labry Apartments, up on 36th. It’s the four hundred building. Apartment 17-E. Come up there any time in the afternoon.”

“Today?”

“Certainly today. If you want the job.”

“Sure.” He felt relief from a pressure invisible till now through its ubiquitousness. He remembered the bread in the alley: its cellophane under the street lamp had flashed more than his or her fogged baubles. “You have an office there. What do you do?”

“I’m a psychologist.”

“Oh,” and didn’t narrow his eyes. “I’ve been to psychologists. I know something about it, I mean.”

“You do?” She touched the lion’s cheek, not leaning. “Well, I think of myself as a psychologist on vacation right now.” Mocking him a little: “I only give advice between the hours of ten and midnight, down at Teddy’s. That’s if you’ll have a drink with me.” But that mocking was friendly.

“Sure. If the job works out.”

“Go on over when you get ready. Tell whoever’s there that Mrs. Brown—Madame Brown is the nickname they’ve given me at Teddy’s, and since I saw you there I thought you might know me by it—that Mrs. Brown told you to come up. Possibly I’ll be there. But they’ll put you to work.”

“Five dollars an hour?”

“I’m afraid it isn’t that easy to find trustworthy workers now that we’ve got ourselves into this thing.” She tried to look straight up under her eyelids. “Oh no, people you can trust are getting rarer and rarer. And you!” Straight at him: “You’re wondering how I can trust you? Well, I’ve seen you before. And you know, we really are at that point. I begin, really, to think it’s too much. Really too much.”

“Get your morning paper!”

“Muriel! Oh, now Muriel! Come back here!”

“Get your morning—Hey, there, dog. Quiet down. Down girl!”

“Muriel, come back here this instant!”

“Down! There. Hey, Madame Brown. Got your paper right here.” Maroon bells flapping, Faust stalked across the street. Muriel danced widdershins about him.

“Hello, old girl.”

“Good morning there,” Madame Brown said. “It is about time for you to be along, Joaquim, isn’t it?”

“Eleven-thirty, by the hands on the old church steeple.” He cackled. “Hi there; hi there, young fellow,” handing one paper, handing another.

Madame Brown folded hers beneath her arm.

He let his dangle, while Faust howled to no one in particular, “Get your morning paper,” and went on down the street. “Bye, there, Madame. Good morning. Get your paper!”

“Madame Brown?” he asked, distrusting his resolve.

She was looking after the newspaper man.

“What are those?”

She looked at him with perfect blankness.

“I’ve got them.” He touched his chest. “And Joaquim’s got a little chain tight around his neck.”

“I don’t know.” With one hand, she touched her own cheek, with the other, her own elbow: Her sleeve was some cloth rough as burlap. “You know, I’m really not sure. I like them. I think they’re pretty. I like having a lot of them.”

“Where did you get them?” he asked, aware he broke the custom Faust had so carefully defined the day before. Hell, he was still uneasy with her dog, and with her transformation between smoke and candlelight.

“A little friend of mine gave them to me.” She had the look, yes, of someone trying not to look offended.

He shifted, let his knees bend a little, his toes go, nodded.

“Before she left the city. She left me, left the city. And she gave me these. You see?”

He’d asked. And felt better for the violence done, moved his arm from the shoulder…his laughter surprised him, broke out and became huge.

Over it, he heard her sudden high howl. With her fist on her chest, she laughed too, “Oh, yes!” squinting. “She did! She really did. I was never so surprised in all my life! Oh, it was funny—I don’t mean funny peculiar, though it certainly was. Everything was, back then. But it was funny ha-ha. Ha-ha-ha-haaaaa.” She shook the sound about her. “She—” almost still—“brought them to me in the dark. People shouting around out in the halls, and none of the lights working. Just the flickering coming around the edge of the shades, and the terrible roaring outside…Oh, I was scared to death. And she brought them to me, in handfuls, wound them around my neck. And her eyes…” She laughed again, though that cut all smile from him. “It was strange. She wound them around my neck. And then she left. There.” She looked down over the accordion of her neck, and picked through the loops. “I wear them all the time.” The accordion opened. “What do they mean?” She blinked at him. “I don’t know. People who wear them aren’t too anxious to talk about them. I’m certainly not.” She leaned a little closer. “You’re not either. Well, I’ll respect that in you. You do the same.” Now she folded her hands. “But I’ll tell you something: and, really there’s no reason behind it, I suppose, other than that it seems to work. But I trust people who have them just a little more than those who don’t.” She shrugged. “Probably very silly. But it’s why I offered you that job.”

“Oh.”

“I suspect we share something.”

“Something happened,” he said, “when we got them. Like you said. That we don’t like to talk about.”

“Then again, it could be nothing more than that we happen to be wearing the same…” She rattled the longest strand.

“Yeah.” He buttoned another button. “It could be.”

“Well. I’ll drop in on you at the Richards’ later in the afternoon. You will be there?”

He nodded. “Four hundred, on 36th Street…”

“Apartment 17-E,” she finished. “Very good. Muriel?”

The dog clicked back from the gutter.

“We’ll be going now.”

“Oh. Okay. And thanks.”

“Perfectly welcome. Perfectly welcome. I’m sure.” Madame Brown nodded, then ambled down the street. Muriel caught up, to circle her, this time deasil.

He walked barefoot through the grass, expectation and confusion hobbling. Anticipation of labor loosened tensions in his body. At the fountain, he let the water spurt in his eyes before he flooded and slushed, with collapsing cheeks, water between filmed teeth. With his forearm he blotted the tricklings, squeegeed his eyelids with rough, toad-wide fingers, then picked up his paper, and, blinking wet lashes, went back up to the trees.

Lanya still lay on her belly. He sat on the drab folds. Her feet, toes in, stuck from under the blanket. An olive twist lay over the trough of her spine, shifting with breath. He touched her wrinkled instep, moved his palm to her smooth heel. He slid his first and second finger on either side of the tendon there. The heel of his hand pushed back the blanket from her calf, slowly, smoothly, all the way till pale veins tangled on the back of her knee. His hand lay on the slope of her thigh.

Her calves were smooth.

His heart, beating fast, slowed.

Her calves were unscarred.

He breathed, and with it was the sound of air in the grass around.

Her calves had no scratch.

When he took his hand away, she made some slumber sound and movement. And didn’t wake. He opened today’s paper and put it on top of yesterday’s. Under the date, July 17, 1969, was the headline:

MYSTERIOUS RUMORS!

MYSTERIOUS LIGHTS!

Would your editor ever like some pictures with this one! We, unfortunately, were asleep. But from what we can gather, shortly after midnight last night—so far twenty-six versions of the story have come in, with contradictions enough to oblige our registering an official editorial doubt—the fog and smoke blanketing Bellona these last months were torn by a wind at too great an altitude to feel at street level. Parts of the sky were cleared, and the full—or near full—moon was, allegedly, visible—as well as a crescent moon, only slightly smaller (or slightly larger?) than the first!

The excited versions from which we have culled our own report contain many discrepancies. Here are some: The full orb was the usual moon, the crescent was the intruder.

The crescent was the real moon, the full, the impostor. A young student says that, in the few minutes these downright Elizabethan portents were revealed, he made out markings on the full disk that prove it was definitely not our moon.

Two hours later, someone came into the office (the only person so far who claims to have caught any of this phenomenon through an admittedly low-power telescope) to assure us the full disk definitely was the moon, while the crescent was bogus.

In the six hours since the occurrence (as we write, into the dawn), explanations offered the Times have ranged from things so science-fictiony we do not pretend to understand their arcane machinery, down to the all-purpose heat lightning and weather balloon, perennial explanations for the UFO.

I pass on, as typical, one comment from our own Professor Wellman, who was observing from the July gardens with several other guests: “One, we all agreed, was nearly full; the other was definitely crescent. I pointed out to the Colonel, Mrs. Green, and Roxanne and Tobie, who were with me, that the crescent, which was lower in the sky, was convexed away from the bright area of the higher moon. Moons do not light themselves; their illumination comes from the sun. Even with two moons, the sun can only be in one direction from them both; no matter which phases they are in, if they are both visible in the same quarter of the sky, both should be light on the same side—which was not the case here.”

To which your editor can only say that any “agreement,” “certainty,” or “definiteness” about these moons are cast into serious doubt—unless we are prepared to make even more preposterous speculations about the rest of the cosmos…?

No.

We did not see it.

Which leaves us, finally, in this editorial position: We are sure something happened in the sky last night. But to venture what it was would be absurd. Brand new moons do not appear. In the face of the night’s hysteria, we should like to point out, quietly, that whatever happened is explicable: Things are—though this, admittedly, is no guarantee we shall ever have the explication.

What seems, both oddly and interestingly, to have been agreed on by all who witnessed, and must therefore be accepted by all who did not, is the name for this new light in the night: George.

The impetus to appellation we can only guess at; and what we guess at we do not approve of. At any rate, on the rails of rumor, greased with apprehension, the name had spread the city by the time the first report reached us. The only final statement we can make with surety: Shortly after midnight, the moon and something called George, easy enough to mistake for a moon, shone briefly on Bellona.

2

“What are you doing,” she whispered through leaves, “now?”

Silent, he continued.

She stood, shedding blankets, came to touch his shoulder, looked down over it. “Is that a poem?”

He grunted, transposed two words, gnawed at his thumb cuticle, then wrote them back.

“Um…” she said, “do you mean making a hole through something, or telling the future?”

“Huh?” He tightened his crossed legs under the notebook. “Telling the future.”

“A-u-g-u-r.”

“Whoever wrote this notebook spells it differently on another page.” He flipped pages across his knees to a previous, right-hand entry:

A word sets images flying from which auguries we read…

“Oh…he did spell it right.” Back on the page where he had been writing, he crossed and recrossed his own kakograph till the bar of ink suggested a word beneath half again as long.

“Have you been reading in there?” She kneeled beside him. “What do you think?”

“Hm?”

“I mean…the guy who wrote that was strange.”

He looked at her. “I’ve just been using it to write my own things. It’s the only paper I’ve got, and he leaves one side of each page blank.” His back slumped. “Yeah. He’s strange,” but could not understand her expression.

Before he could question it with one of his, she asked, “Can I read what you’re doing?”

He said, “Okay,” quickly to see what it would feel like.

“Are you sure it’s all right?”

“Yeah. Go on. It’s finished anyway.”

He handed her the notebook: His heart got loud; his tongue dried stickily to the floor of his mouth. He contemplated his apprehension. Little fears at least, he thought, were amusing. This one was large enough to joggle the whole frame.

Clicking his pen point, he watched her read.

Blades of hair dangled forward about her face like orchid petals, till—“Stop that!”—they flew back.

They fell again.

He put the pen in his shirt pocket, stood up, walked around, first down the slope, then up, occasionally glancing at her, kneeling naked in leaves and grass, feet sticking, wrinkled soles up, from under her buttocks. She would say it was silly, he decided, to show her independence. Or she would Oh and Ah and How wonderful it to death, convinced that would bring them closer. His hand was at the pen again—he clicked it without taking it from his pocket, realized what he was doing, stopped, swallowed, and walked some more. Lines on Her Reading Lines on Her he pondered as a future title, but gave up on what to put beneath it; that was too hard without the paper itself, its light red margin, its pale blue grill.

She read a long time.

He came back twice to look at the top of her head. And went away.

“It…”

He turned.

“…makes me feel…odd.” Her expression was even stranger.

“What,” he risked, “does that mean?” and lost: it sounded either pontifical or terrified.

“Come here…?”

“Yeah.” Crouching beside her, his arm knocked hers; his hair brushed hers as he bent. “What…?”

Bending with him, she ran her finger beneath a line. “Here, where you have the words in reverse order from the way you have them up here—I think, if somebody had just described that to me, I wouldn’t have found it very interesting. But actually reading it—all four times—it gave me chills. But I guess that’s because it works so well with the substance. Thank you.” She closed the notebook and handed it back. Then she said, “Well don’t look so surprised. Really, I liked it. Let’s see: I’m…delighted at its skill, and moved by its…well, substance. Which is surprising, because I didn’t think I was going to be.” She frowned. “Really, you…are staring something fierce, and it makes me nervous as hell.” But she wouldn’t look down.

“You just like it because you know me.” That was also to see what it felt like.

“Possibly.”

He held the notebook very tight, and felt numb.

“I guess—” she moved away a little—“somebody liking it or not doesn’t really do you any good.”

“Yeah. Only you’re scared they won’t.”

“Well, I did.” She started to say more, didn’t. Was that a shrug? Finally, she looked from beneath the overhanging limbs. “Thank you.”

“Yeah,” he said almost with relief. Then, as though suddenly remembering: “Thank you!”

She looked back, confusion working through her face toward some other expression.

“Thank you,” he repeated, inanely, palms pressing the notebook to his denim thighs, growing wet. “Thank you.”

The other expression was understanding.

His hands worked across each other like crabs, crawled round himself to hug his shoulders. His knees came up (the notebook dropped between them) to bump his elbows. A sudden welling of…was it pleasure? “I got a job!” His body tore apart; he flopped, spread-eagle, on his back. “Hey, I got a job!”

“Huh?”

“While you were asleep.” Pleasure rushed outward into hands and feet. “That lady in the bar last night; she came by with her dog and gave me this job.”

“Madame Brown? No kidding. What kind of job?” She rolled to her stomach beside him.

“For this family. Named Richards.” He twisted, because the chain was gnawing his buttocks. Or was it the notebook’s wire spiral? “Just cleaning out junk.”

“Well there’s certainly enough junk—” she reached down, tugged the book loose from beneath his hip—“around Bellona to clean out.” She lay it above his head, propped her chin on her forearms. “A pearl,” she mused. “Katherine Mansfield once described San Francisco, in a letter to Murray, as living on the inside of a pearl. Because of all the fog.” Beyond the leaves, the sky was darkly luminous. “See.” Her head fell to the side. “I’m literate too.”

“I don’t think—” he frowned—“I’ve ever heard of Katherine…?”

“Mansfield.” Then she raised her head: “Was the reference in the thing you wrote, to that Mallarmé poem…” She frowned at the grass, started tapping her fingers. “Oh, what is it…!”

He watched her trying to retrieve a memory and wondered at the process.

“Le Cantique de Saint Jean! Was that on purpose?”

“I’ve read some Mallarmé…” He frowned. “But just in those Portuguese translations Editora Civilizaçáo put out…No, it wasn’t on purpose I don’t think…”

“Portuguese.” She put her head back down. “To be sure.” Then she said: “It is like a pearl. I mean here in Bellona. Even though it’s all smoke, and not fog at all.”

He said: “Five dollars an hour.”

She said: “Hm?”

“That’s what they’re going to pay me. At the job.”

“What do you want with five dollars an hour?” she asked, quite seriously.

Which seemed so silly, he decided not to insult her by answering.

“The Labry Apartments,” he went on. “Four hundred, 36th Street, apartment 17-E. I’m supposed to go up there this afternoon.” He turned to look at her. “When I come back, we could get together again…maybe at that bar?”

She watched him a moment. “You want to get together again, don’t you.” Then she smiled. “That’s nice.”

“I wonder if it’s late enough to think about going over there?”

“Make love to me once more before you go.”

He scrunched his face, stretched. “Naw. I made love to you the last two times.” He let his body go, glanced at her. “You make love to me this time.”

Her frown fell away before, laughing, she leaned on his chest.

He touched her face.

Then her frown came back. “You washed!” She looked surprised.

He cocked his head up at her. “Not very much. In the john down there, I splashed some water on my face and hands. Do you mind?”

“No. I wash, myself, quite thoroughly, twice—occasionally even three times a day. I was just surprised.”

He walked his fingers across her upper lip, beside her nose, over her cheek—like trolls, he thought, watching them.

Her green eyes blinked.

“Well,” he said, “it’s not something I’ve ever been exactly famous for. So don’t worry.”

Just as if she had forgotten the taste of him and was curious to remember, she lowered her mouth to his. Their tongues blotted all sound but breath while, for the…fifth time? Fifth time, they made love.

The glass in the right-hand door was unbroken.

He opened the left: a web of shadows swept on a floor he first thought was gold-shot blue marble. His bare foot told him it was plastic. It looked like stone…

The wall was covered with woven, orange straw—no, the heel of his palm said that was plastic too.

Thirty feet away, in the center of the lobby—lighting fixtures, he finally realized—a dozen grey globes hung, all different heights, like dinosaur eggs.

From what must have been a pool, filled with chipped blue rock, a thin, ugly, iron sculpture jutted. Passing nearer, he realized it wasn’t a sculpture at all, but a young, dead tree.

He hunched his shoulders, hurried by.

The “straw”-covered partitioning wall beside him probably hid mailboxes. Curious, he stepped around it.

Metal doors twisted and gaped—like three rows, suddenly swung vertical (the thought struck with unsettling immediacy), of ravaged graves. Locks dangled by a screw, or were missing completely. He passed along them, stopping to look at one or another defaced name-plate, bearing the remains of Smith, Franklin, Howard…

On the top row, three from the end, a single box had either been repaired, or never prised: Richards: 17-E, white letters announced from the small black window. Behind the grill slanted the red, white, and blue edging of an airmail envelope.

He came out from the other side of the wall, hurried across the lobby.

One elevator door was half-open on an empty shaft, from which drifted hissing wind. The door was coated to look like wood, but a dent at knee level showed it was black metal. While he squatted, fingering the edge of the depression, something clicked: a second elevator door beside him rolled open.

He stood up, stepped back.

There were no lights in the other car.

Then the door on the empty shaft, as if in sympathy, also finished opening.

Holding his breath and his notebook tight, he stepped into the car.

“17” lit his fingertip orange. The door closed. The number was the only light. He rose. He wasn’t exactly afraid; all emotion was in super solution. But anything, he understood over his shallow breath, might set it in fantastic shapes.