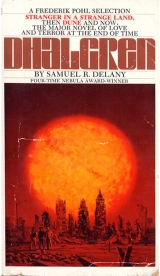

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 34 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“What?”

“I remember sitting there and asking myself if this was what the inside of insanity felt like—Ah, there: you’ve taken offense.”

He hadn’t. But now wondered if he should.

“Well, I’m sorry. That’s what I thought, anyway.”

“You were really that scared?”

“You weren’t?”

“I guess a lot of people around me were. I thought about all the terrible things it could have been—like everybody else. But if it was any of them, there wasn’t anything I could do.”

“You really are almost as weird as people keep trying to make us think you are. Look, when you come up short against the edge like that, when you discover the earth really is round, when you find out you’ve killed your father and married your mother after all, or when you look at the horizon and see something, like that, rising—man, you have to have some sort of human reaction: laugh, cry, sing, something! You can’t just lie down and take a nap.”

Kid lingered in the ruins of his confusion. “I…did a lot of laughing.”

Tak snorted again. “Okay, so you’re not that flippy I’d just hate to think you were as brave as everybody keeps going on you are.”

“Me?” This couldn’t, Kid thought, be what the inside of courage felt like.

“Excuse me,” the southwestern voice said from Kid’s other side. “You were pointed out to me as…the Kid?”

Kid turned, with his confusion. “Yeah…?”

Kamp looked at it, and laughed. Kid decided he liked him. Kamp said, “I’m supposed to deliver a message to you, from Roger.”

“Huh?”

“He told me if I came here I would probably meet you. He’d like—if it’s all right with you—if you’d come up to the house three Sundays from now. He says that he’ll be squeezing more time together, so it will be in slightly less than two weeks—now I don’t know how you guys put up with that—” He laughed again. “Roger wants to have a party for you. For your book.” The Captain paused with a consideration nod. “Saw it. Looks good. Good luck on it, now.”

Kid wondered what to say. He tried: “Thank you.”

“Roger said to come in the evening. And bring twenty or thirty friends, if you want. He says it’s your party. It starts at sunset; in three Sundays.”

“Presumptuous bastard,” Tak said. “Sunset? He might at least wait and see if there’s a tomorrow morning.” With his forefinger he hooked down his cap visor and walked off.

Kid was pondering statements to place into the silence, when Kamp apparently decided he’d try: “I’m afraid I don’t know much about poetry.”

Liked him, Kid felt. But for the life of him he didn’t know why.

“I read some of it at Roger’s, though. But if I started asking questions about it, now, I’d probably just end up looking worse than I already do.”

“Mmmm.” Kid nodded and pondered. “You get tired of people asking you all those questions?”

“Yes. But it wasn’t too bad this evening. At least we were talking about something real. I mean something that happened, today. It’s better than all those discussions where they ask you whether, as an astronaut, you believe in long hair, abortions, race relations, or the pill.”

“You’re a very public man, aren’t you? You say you’re not really into the space program anymore. But you’re doing public relations work for them right now.”

“Exactly what I’m doing. I don’t claim to be doing anything else. Except enjoying myself. They’re beginning to accept the idea of having a nonconformist doing front work for them.” Kamp glanced around. “Though I suspect compared to most of you guys here, even some of the ducks up at Roger’s, I’m more or less the image of the establishment, folk songs or not, hey? Well, that makes me Bellona’s biggest nonconformist. I don’t mind.”

“Questions like, did you leave, or were you kicked out—what do you do when people ask you the same questions over and over? Especially the embarrassing ones.”

“If you’re a public man, as soon as you get a question more than three times, you figure out the most honest public answer you can give. Especially to the embarrassing ones.

“Is that a question you get asked a lot?”

“Well,” Kamp mulled, “more times than three.”

“Then I guess it would be okay to ask you questions about the moon.” Kid grinned.

Kamp nodded. “Sounds like a pretty safe topic.”

“Can you tell me something about the moon you’ve never told anybody else before?”

After a second, Kamp laughed. “Now that is a new one. I’m not sure I know what you mean.”

“You were there. I’d like to know something about the moon that someone could only know who was actually on it. I don’t mean anything big. But just something.”

“The whole flight was broadcast. And we were pretty thorough in our report. We tried to take pictures of just about everything. Also, that’s a few years ago; and we were only out walking around for six and a half hours.”

“Yeah, I know. I watched it.”

“Then I still don’t get you.”

“Well: I could bring a couple of television cameras in here, say, and take a lot of pictures, and report on all the people, tell how many were here or what have you. But afterward, if somebody asked me to tell them something that wasn’t in the coverage, I’d close my eyes and sort of picture the place. Then I might say, well, on the back of the counter with the bottles, the bottle second from the left—I don’t remember what the label was—but the little cone of glass at the bottom was just above the top of the liquor.” Kid opened his eyes. “See?”

Kamp ran his knuckles under his chin. “I’m not used to thinking like that. But it’s interesting.”

“Try. Just mention some rock, or collection of rocks, or shape on the horizon that you didn’t mention to anyone else.”

“We took photographs of all three hundred and sixty degrees of the horizon—”

“Then something else.”

“It would be easier to tell you something like that about the module. I remember…” Then he cocked his head.

“I guess that would do,” Kid said. “But I’d prefer it was about the moon.”

“Hey, here’s something.” Kamp leaned forward. “When I got down the ladder—do you remember the foil-covered footpads that the modules rested on? You say you watched it.”

Kid nodded.

“Well, now, when I was getting some of the equipment out of the auxiliary compartments—I’d been actually on surface maybe a minute, maybe not quite: A lot of people, back before the probe shots, had the idea the moon was covered with dust. But it was purplish brown dirt and rock and gravel. The feet didn’t sink at all.”

Kid thought: Translation.

Kid thought: Transition.

“The module’s feet were on universal joints, you know? Anyway. The one to the left of the entrance was tilted on a small rock, maybe two inches through. The shadows were pretty sharp. I guess when I was passing by it, my shadow passed over the module foot. And the shadow from the pad, made by the rock it was sitting on, and my shadow, joining it, for just a second made it look like something moved under there. You know? I was excited, see, because I was on the moon. And it just isn’t like anything in the training sessions at all. But I do remember for maybe three seconds, while I was going on doing all the things I had to do, thinking, ‘There’s a moon-mouse, or a moon-beetle under there.’ And feeling silly that I couldn’t say anything—I was broadcasting all the time, describing what I saw—because there couldn’t be anything alive on the moon, right? Like I said, it just took me a couple of seconds to figure out what it really was. But for a moment it was pretty funny. Now there. That’s something I never told anybody…no, I think I did mention it once to Neil, when I got back. But I don’t think he was listening. And I told it just like a joke.”

Formation. Kid thought: Transformation.

“Is that the sort of thing you mean?”

Kid had expected Kamp to be smiling at the end of his story. But each feature rested just within the limit of sobriety.

“Yes. What are you thinking now?”

“I’m wondering why I told you. But I guess Bellona is the kind of place you come to do something new, right? See new things. Do new things.”

“What do people say about this place, outside? Do people who come back from here tell you all about life under the fog? Who did you talk to that made you want to come?”

“I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who’s actually gone and come back from here—except Ernest Newboy. And we just shook hands in passing and didn’t get a chance to talk. I’ve met some people who were evacuated back at the beginning. Once they stopped trying to cover it on TV, people stopped talking, I guess—people don’t talk about it now.”

Kid let his head lean.

“They refer to it…” Kamp said. “You can be sitting around somebody’s living room, in Los Angeles or Salt Lake, talking about this, that, or the other, and somebody might mention somebody he used to know here. A friend of mine in physics, driving down from the University of Montana, said he gave two girl hitch-hikers a lift who told him they were going here. He thought that was very strange, because, the last the paper reported, there was supposed to be some national guards around.”

“That’s what I heard too,” Kid said. “But that was awhile before I came. I haven’t seen any.”

“How long have you been here?”

“I don’t know. It feels like a pretty fair time. But I really couldn’t tell you.” Kid shrugged. “I wish I did know more than that…sometimes.”

Kamp was trying not to frown. “Roger said you would be an interesting person. You are.”

“I’ve never met him.”

“So he told me.”

“I guess you don’t know how long you’re going to stay either?”

“Well now, I haven’t really made up my mind. When I came here, I wasn’t thinking of the trip exactly as a vacation. But I’ve been here a few days, and I’ll tell you, especially with the business this afternoon, I don’t quite know what to make of it.”

“You’re interesting too,” Kid said after a moment. “But I don’t know whether it’s because you’ve been to the moon; or just because you’re interesting. I like you.”

Kamp laughed, and picked up his beer. “Come on, since we’re trying so hard to be honest: What reason could you possibly have for liking me?”

“Because even though you’re a public person—and public people are great if you happen to be the public—some of the private ‘you’ gets through. I think you’re very proud of the things you’ve done, and you’re modest about them, and don’t want to talk about them unless it’s serious—even joking serious. To protect that modesty, I think you’ve had to do some things that haven’t made you all that happy.”

Measuredly, Kamp said, “Yes. But what do you get by telling me that?”

“Because I like you, I want you to trust me a little. If I can show you I understand something about you, perhaps you will.”

“Ah, ha!” Kamp drew back, ineptly mocking something theatrical. “Just for argument now: Supposing you do know something about me, how do I know you won’t use it against me?”

Kid looked down at the optical jewels on his wrist, turned his wrist: two veins joined beneath the ham of his thumb to run under the chain. “That’s the third time somebody’s asked me that. I guess I’ll have to think of a public answer.”

Tak was talking with someone by the door. Unshaven, and a little wild looking, Jack stepped in. Tak turned to the young deserter, who looked around, looked at Captain Kamp. Tak nodded in corroboration to something. Jack turned, picked up something that could have been a gun leaning against the wall, and practically ran out of the bar.

“I think I’ve figured out an answer already,” Kid said.

Captain Kamp said, “…mmmm,” and then, “so did I.”

Kid grinned. “Good.”

“You know—” Kamp looked down at the counter—“there are some things I’m not happy about. But now, they’re just the things a guy would be reluctant to tell, ordinarily, to…well, one of you fellows with the shaggy hair, the funny clothes, and the beads and things. Or chains…” He looked up. “I am dissatisfied with my life and my work. It’s a very subtle dissatisfaction, and I don’t want to be told to take dope and let my hair grow. I mean that’s just the last thing I want to hear.”

“Why don’t you take dope and let your hair grow? See, it wasn’t that bad. Now that the worst has happened, maybe you can go and talk about it. I’ll just listen.”

Kamp laughed. “I’m dissatisfied with my life on earth. How’s that? Not clear, I guess. Look—I’m not the same person I was before I went to the moon—maybe this is the sort of thing you were asking about. Perhaps it’s the sort of thing that should only be told to one person. But I’ve told a couple of dozen: You know the world is round, and that the moon is a small world circling it. But you live in a world of up and down, where the land is a surface. But for me, just the visual continuity from that flat surface to a height where the edge of the earth develops a curve, to where that curve is a complete circle, to where the little soap-colored circle hanging in front of you enlarges to the size the Earth was, and then you come down. And suddenly that circle is a surface—but up and down is already not quite the same thing. We danced when we got out on the moon. What else could we do with that lightness? You know, seeing a film backward isn’t the same experience as seeing it forward in reverse. It’s a new experience, still happening forward in time. What falls out is all its own. Returning from the moon was not the same as going, played backward. We arrived at a place where no one had walked; we left a place where we had danced. The earth we left was peopled by a race that had never sent emissaries to another cosmological body. We returned to a people who had. I really feel that what we did was important—folks starving in India notwithstanding; and if there’s a real threat of world starvation, technology will have to be used to avoid it; and I can’t think of a better way to let people know just how far technology can take us. I was at a point of focus, for six and a half hours. I’m happy with that focus. But I’m not too terribly satisfied with the life on either side. The things that are off are like the things off about the way Bellona looked when we were driving through the first day I got here: there aren’t many people, but there’s no overt signs of major destruction—at least I didn’t see any. It’s grey, and some windows are broken, and here and there are marks of fire. But, frankly, I can’t tell what’s wrong. I still haven’t been able to figure out what’s happened here.”

“I’d like to go to the moon.”

“Cut your hair and stop taking dope.” Kamp’s tongue bulged his upper lip. “You don’t even have to join the services. We have civilians in the program. Worst thing I could say, huh? But it really is the basic requirement. I mean all the rest comes after that. Really.”

He thinks, Kid thought, he may have offended me. Kid tried not to smile.

“You’re frowning,” Kamp said. “Come on, now. Turnabout’s fair play…well, all right. Tell me this. Are you all that happy? Be honest now.”

Tak was ambling, slow and aimless, across the room.

“I think,” and Kid felt his feelings change to fit the frown, “there’s something wrong with your question, you know? I spend a lot of time happy; I spend a lot of time unhappy; I spend a lot of time just bored. Maybe if I worked real hard at it, I could avoid some of the happiness, but I doubt it. The other two I know I’m stuck with…”

Kamp was brightly attentive to something not more than a degree or so outside of Kid’s face. Well, Kid reflected, I said I’d listen. When Kid had been silent five seconds, Kamp said:

“I’m not the same person I was before I went to the moon. Several people have explained to me that nobody else on Earth is either. Someone told me once that I have begun to heal the great wound inflicted on the human soul by Galileo when he let slip the Earth was not the center of the Universe. No, I am not really satisfied now. I wonder at that light in the sky, this afternoon. I wonder at the stories I’ve heard about two moons when I know, first hand, what I do about the one. But I observe it first from a very different position than you. We could sit and discuss and have conferences and seminars until a much more reassuring sun came up, and I still doubt if I could say anything meaningful to you, or you could say anything meaningful to me. At least about that.”

“Hey, there.” Tak put his hand on Kid’s shoulder—but was talking to Kamp: “That was my friend Jack. You know, we have a good number of army deserters with us. I told him we had a full-fledged Captain with us this evening. He wanted to know whether you were a deserter too. I told him that as far as I knew you were still a member in good standing. I’m afraid he just turned around and ran without even waiting to find out you were in the Navy. Are you on your way, Captain?”

Kamp nodded, raised his bottle. “Glad I got a chance to meet you, Kid. If I don’t see you before, I’ll catch you at Roger’s.” Again he nodded at Tak, and turned.

“I hope I make him as uncomfortable as he keeps pretending I do.” Tak sucked his teeth. “Wish he’d come in uniform. Before I went on to more complicated pleasures, I used to have a real passion for seafood.”

“You’re flattering yourself.”

Tak gave a few small nods. “Possibly, very possibly. Hey, I’m sorry I kicked you out last night. Come home with me. Fuck me.”

“Naw. I’m looking for Lanya.”

Tak enfolded his beer with his big, pale hands and looked down the bottle mouth. “Oh.” Then he said: “Then come with me somewhere else. I want to show you something. You probably want to see it, too.”

“What is it?”

“On the other hand, maybe you have seen it already and you’re not interested.”

“But you’re not going to tell me what it is?”

“Nope.”

“Come on,” Kid said. “Show me.”

Tak clapped Kid’s shoulder, then pushed away from the bar. “Let’s go.”

Between the buildings, black bulged down, a tarpaulin full of rain.

“This is the sort of night I’d give anything for a star. When I was younger I used to try to learn the constellations, but I never really got them down. I can find the Big Dipper.” Tak opened his zipper. “Can you do that?”

“I know them pretty well now. But I learned them a few years ago, back when I was traveling, and on boats and stuff. They’re the only things that stay the same when you’re really moving around a lot. I picked up this pocket book for fifty cents, when I was in Japan—it was an American book though. In about two weeks I could pick out just about anything.”

“Mmmmm.” Tak glanced up as they neared the corner lamp. “Just as well we can’t see them, then. I mean, are you ready to have to learn a whole new set?” The shadow drew over his face like a shade. “This way.”

The street sloped. At the next corner they turned again. Half a block later Kid asked, “Can you see anything at all?”

“No.”

“But you know where we’re going…?”

“Yes.”

The smell of burning had again become distinct. The air was cooler, much cooler: he felt a crack in the pavement beneath his bare foot. Something with edges rolled away from his boot. The woody odors sifted. For one instant they passed through a smell that brought back—it hit with the force of hallucination: a cave in the mountains where something had crackled in a large, brass dish on the wet stone, while above he’d seen, glittering…

The chain around him tingled and tickled as though memory had sent current through it. But the particular odor (wet leaves over dry, and a fire, and something decayed…) was gone. And cool as the darkness was, it was dry, dry…

Edged by a vertical wall, light a long way away diffused in smoke.

At the corner, Tak looked back. “Checking to make sure you were still with me. You don’t make much noise. We’re going across there.” Tak nodded forward and they crossed the street, shoulder bumping shoulder.

Beyond plate glass, an amber light silhouetted black wire forms.

“What sort of store was this?” Kid asked, behind Tak who was opening the door.

It sounded like a machine was running in the basement. Empty shelves lined the walls, and the wire frames were display racks. The light came from no more than a single bulb somewhere on the stairwell. Tak went to the cash register. “First time I came in here, would you believe there was still eighty dollars in the drawer?”

Tak rang.

The drawer trundled out.

“Still there.”

He closed it.

In the cellar the sound stopped, then started again: only now it didn’t sound like a machine at all, but someone moaning.

“We want to go downstairs,” Tak said.

Someone had scattered pamphlets on the steps. They whispered under Kid’s bare foot. “What was this place?” Kid asked again. “A bookstore?”

“Still is.” Tak peered out where the single hanging bulb lit empty shelves. “Paperback department down here.”

Tacked to an edge was a hand-lettered sign: ITALIAN LITERATURE.

A youngster with very long hair sat cross-legged on the floor. He glanced up, then closed his eyes, faced forward, and intoned: “Om…” drawing the last sound until it became the mechanical growl Kid had heard when they’d entered.

“Occupied tonight,” Tak said, softly. “Usually there’s no one here.”

Between the checked flannel lapels, the boy’s chest ran with sweat. Cheek bones glistened above his beard. He’d only glanced at them, before closing his eyes again.

It’s cool, Kid thought. It’s so much cooler.

Beside ITALIAN LITERATURE was POLITICAL SCIENCE. There were no books on that one either.

Kid stepped around the boy’s knees and looked up at PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE (equally empty) and walked on to PHILOSOPHY. All the shelves, it seemed, were bare.

“Ommmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm…”

Tak touched Kid’s shoulder. “Here, this is what I wanted to show you.” He nodded across the room.

Kid followed Tak around AMERICAN LITERATURE which was a dusty wooden rack in the middle of the floor.

The unfrosted bulb pivoted shadows about them.

“I used to come down here for all my science fiction,” Tak said, “until there wasn’t anything on the shelves anymore. In there. Go ahead.”

Kid stepped into the alcove and stubbed his booted toe (thinking: Fortunately), hopped back, looked up: The ivory covers recalled lapped bathroom tiles.

All but the top shelf was filled with face-out display. He looked again at the carton he had kicked. The cover wagged. As he stared into the box, something focused: a shadow, first fallen across his mind at something Lanya had said at the nest, almost blurred out by the afternoon’s megalight, now, under the one unfrosted bulb, lay outlined and irrefutable: As manuscripts did not become galleys overnight, neither did galleys become distributed books. Manymore than twenty-four hours had passed since he had corrected proofs with Newboy in the church basement.

Frowning, he bent to pick out a copy, paused, reached for one on the shelf, paused again, looked back at Tak, who had his fists in his jacket pockets.

Kid’s lips whispered at some interrogative. He looked at the books again, reached again. His thumb stubbed the polished cover-stock.

He took one.

Three fell; one slid against his foot.

Tak said: “I think it’s very quaint of them to put it in POETRY,” which is what the sign above said. “I mean they could have filled up every shelf in the God-damn store. There’re a dozen cartons in the back.”

Thumb on top, three fingers beneath, Kid tried to feel the weight; he had to jog his hand. There was a sense of absence which was easiest to fill with

BRASS

ORCHIDS

lettered in clean shapes with edges and serifs his own fingers could not have drawn, even with French curve and straightedge. He reread the title.

“Ommmmmmmmmmmmmmm…” The light blacked and went on again; the “…mmmmmmmmmm…” halted on a cough.

Kid looked over the six, seven, eight filled shelves. “That’s really funny,” he said, and wished the smile he felt should be on his face would muster his inner features to the right emotions. “That’s really…” Suddenly he took two more copies, and pushed past Tak for the stair. “Hey,” he said to the boy. “Are you all right?”

The sweating face lifted. “Huh?”

“What’s the matter with you?”

“Oh, man!” The boy laughed weakly. “I’m sick as a dog. I’m really sick as a fucking dog.”

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s my gut. I got a spastic duodenum. That’s like an ulcer. I mean I’m pretty sure that’s what it is. I’ve had it before, so I know what it feels like.”

“What are you doing here, then?”

The boy laughed again. “I was trying yoga exercises. For the pain. You know you can control things like that, with yoga.”

Tak came up behind Kid. “Does it work?”

“Sometimes.” The boy took a breath. “A little.”

Kid hurried on up the steps.

Tak followed.

From the top step Kid looked around at the shelves, and turned to Tak, who said:

“I was just thinking, I really was, about asking you to autograph this for me.” He held up the copy and snorted rough laughter. “I really was.”

Kid decided not to examine the shape this thought made, but caught the mica edge: It’s not not having: It’s having no memory of having. “I don’t like that sort of shit anyway…” he said, awed at his lie, and looked at Tak’s face, all shadowed and flared with backlight. He searched the black oval for movement. It’s there anyway, he thought; he said: “Here. Gimme,” and got the pen from the vest’s buttonhole.

“What are you going to do?” Tak handed it over.

Kid opened it on the counter by the register, and wrote: “This copy of my book is for my friend, Tak Loufer.” He frowned a moment, then added, “All best.” The page looked yellow. And he couldn’t read what he’d written at all, which made him realize how dim the light was. “Here.” He handed it back. “Let’s go, huh?”

“Ommmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm…”

“Yeah.” Tak glanced downstairs and sucked his teeth. “You know?” They walked to the door. “When you took it from me, I thought you were going to tear it up.”

Kid laughed. Perhaps, he thought, I should have. And thinking it, decided what he had put was best. “You know—” as they stepped into the night, Kid felt his fingers dampen on the cover: fingerprints?—“people talk about sexual inadequacy? That doesn’t have anything to do with whether you can get a hard-on or not. A guy goes out looking for his girlfriend and doesn’t even know where she lives, and doesn’t seem to have bothered to find out…You said Madame Brown might know?”

“I think so,” Tak said. “Hey, you’re always talking about your girlfriend. Right now, do you have a boyfriend?”

Kid figured they had reached the corner. On the next step he felt the ball of his bare foot hung over the cup. “Yeah, I guess I do.” They stepped down.

“Oh,” Tak said. “Somebody told me you’re supposed to be making it with some kid in the scorpions.”

“I could get to hate this city—”

“Ah, ah, ah!” Tak’s voice aped reproval. “Rumor is the messenger of the gods. I’m sort of curious to find out what you wrote in my book.”

At which Kid started to balk, found his own balking funny, and smiled. “Yeah.”

“And of course, the poems too. Well…”

Kid heard Tak’s footsteps stop.

“…I go this way. Sure I can’t convince you…?”

“No.” He added: “But thanks. I’ll see you.” Kid walked forward thinking, That’s nuts. How does anybody know where anything is in this, and thought that thought seven or eight times through, till, without breaking stride, he realized: I cannot see a thing and I am alone. He pictured great maps of darkness torn down before more. After today, he thought idly, there is no more reason for the sun to rise. Insanity? To live in any state other than terror! He held the books tightly. Are these poems mine? Or will I discover that they are improper descriptions by someone else of things I might have once been near; the map erased, aliases substituted for each location?

Someone, then others, were laughing.

Kid walked, registering first the full wildness of it, the spreading edges; but only at the working street lamp at the far corner, realizing it was humor’s raddle and play.

Two black men, in the trapezoid of light from a doorway, were talking. One was drinking a can of beer or Coke. From across the street, a third figure (Kid could see the dark arms were bare from here, that the vest was shiny) ambled up.

The street lamp pulsed and died, pulsed and died. Black letters on a yellow field announced, and announced, and announced:

JACKSON AVENUE

Kid walked toward them, curious.

“She run up here…” The tall one explained, then laughed once more. “Pretty little blond-headed thing, all scared to death; you know, she stopped first, like she gonna turn around and run away, with her han’ up in front of her mouth. Then she a’ks me—” The man lowered his head and raised his voice: “‘Is George Harrison in there? You know, George Harrison, the big colored man?’” The raconteur threw up his head and laughed again. “Man, if I had ’em like George had ’em…” In his fist was a rifle barrel (butt on the ground) that swung with his laughter.

“What you tell her?” the heavier one asked, and drank again.

“‘Sure he’s inside,’ I told her. ‘He better be inside. I just come out of there and I sure as hell seen him inside. So if he ain’t inside, then I just don’t know where else he might be.’” The rifle leaned and recovered. “She run. She just turned around and run off down the block. Run just like that!”

The third was a black scorpion with the black vinyl vest, his orchid on a neck chain. It’s like, Kid thought, meeting friends the afternoon the TV had been covering the assassination of another politician, the suicide of another superstar; and for a moment you are complicit strangers celebrating by articulate obliteration some national, neutral catastrophe.

Remembering the noon’s light, Kid squinted in the dark. And wished he were holding anything else: notebook or flower or shard of glass. Awkwardly, he reached back to shove the books under his belt.

The three turned to look.

Kid’s skin moistened with embarrassment.

“…She just run off,” the black man with the gun finally repeated, and his face relaxed like a musician’s at a completed cadence.

The one with the beer can, looking left and right, said, “You scorpions. So you come down here a little, huh?”

“This is the Kid,” the black scorpion explained. “I’m Glass.”

His name, Kid thought (he remembered Spider helping with Siam’s arm on the rocking bus floor…): It isn’t any easier to think of them once their names surface. They might as well be me. Surfaced with-it was a delight at his own lack. But that joy still seemed as dull and expected as a banally Oedipal dream he’d had the first night he’d been assigned a psychiatrist at the hospital.