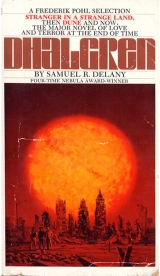

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 55 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“You’re too content to write?”

“You,” I said, “are a politician; and you’re just not going to understand.”

“At least you’re giving me a little more support in my resolve not to read your work. Well, you say you’re still writing. Regardless of any personal preface you might make, even this one, I’m just as interested in your second book as I was in your first.”

“I don’t know if I’m about to waste any time trying to get it to you.”

“If I must arrange to have it hijacked, ink still moist, from beneath the very shadow of your dark quill, I suppose that’s what I’ll have to do. Let’s see, shall we?”

“I’ve got other things to do.” For the first time, I was really angry at his affectation.

“Tell me about them,” he said, in a voice so natural, but following so naturally from the archness, my anger was defeated.

“I…I want you to tell me something,” I said.

“If I can.”

“Is the Father, here at the monastery,” I asked, “a good man?”

“Yes. He’s a very good man.”

“But for me to accept that, you see,” I said, “I have to know I can accept your definition of good. It probably isn’t the same as mine…I don’t even know if I have one!”

“Again, I wish I were allowed to see you. Your voice sounds as though you might be upset about something.” (Which I hadn’t realized; I didn’t feel upset.) “I’m not oblivious to your efforts to keep our talk at a level of honesty I might find tedious if I didn’t have the respect for truth a man forced to tell a great many lies for the most commendable reasons must. I’m not very satisfied with myself, Kid. In the past months, a dozen separate situations have propelled me to the single realization that, to be a good governor, if it is not absolutely necessary to be a good man, it is certainly of inestimable help. Bellona is an eccentric city that fosters eccentric ways. But the reason I’m here, of all eccentric places in this most eccentric place, is because I really want to—”

Dust or something blew into my mouth, got down my throat; I cleared it, thinking: Christ, I hope he doesn’t decide my voice is breaking with emotion!

“—to remedy a little of that dissatisfaction. If he is not a good man, the Father is certainly a generous one. He is allowing me to stay here…Of course there’s always an odd relation between the head of the state and the head of the state-approved religion. After all, I helped set up this place. Same way I helped set up Teddy’s. Of course in this case, the biggest—if easiest—job, given my position with the Times, was making sure there was no publicity. In your present mood, you can probably appreciate that. But, no, my relation to the Father is not that of commoner to priest. On my side, at any rate, it is duplicitous, fraught with doubt. If I didn’t doubt, I wouldn’t be here now. I’m afraid the politics works through the spiritual like rot. The good governor at least wants it to be the best rot possible.”

“Is the Father a good man?” I asked again and tried not to sound at all like I was upset. (Maybe that backfired?)

“Has it occurred to you, my young Diogenes, that if you polished up the chimney of your own lamp, you’d be a little more likely to find this mysterious and miraculous Other you are searching out? Why does it concern you so?”

“So I can live here,” I said, “in Bellona.”

“You’re afraid that for want of one good man the city shall be struck down? You better look back across the train-tracks, boy. Apocalypse has come and gone. We’re just grubbing in the ashes. That simply isn’t our problem anymore. If you wanted out, you should have thought about it a long time back. Oh, you’re very high-minded—and so, at times, am I. Well, as the head of the state religion, the Father does a pretty good job; good enough so that those doing not quite so well would do a bit better not to question—especially if that’s all we can get.”

“What do you think about the religion of the people?” I asked.

“How do you mean?”

“You know. Reverend Amy’s church; George; June; that whole business.”

“Does anyone take that seriously?”

“For a governor,” I said, “you’re pretty out of touch with what the people are into, aren’t you? You’ve seen the things that have shown up in this sky. There’re posters of him all over town. You published the interview, and the pictures that made them gods.”

“I’ve seen some of it, of course. But I’m afraid all that black mysticism and homoeroticism is just not something I personally find very attractive. And it certainly doesn’t strike me as a particularly savory basis for worship. Is Reverend Taylor a good woman? Is George a good…god?”

“I’m not that interested in anybody’s religion,” I told him. “But if you want to bring the purpose of the church down to turning out people who do good things: When I was awfully hungry, she fed me. But when I was hurt and thirsty, someone at your gate told me I couldn’t get a glass of water.”

“Yes. That regrettable incident was reported to me. Things do catch up to you here, don’t they? When you were unpublished, however, I published you.”

“All right.” My laugh was too sharp. “You’ve got the whole thing down, Mr. Calkins. Sure, it’s your city. Hey, you remember the article about me saving the kids from the fire the night of the party? Well, it wasn’t me. It was George. I was just along. But he was down there, searching through the fire, seeing if anybody needed help. I just wandered by; and the only reason I stayed was because he told me the ones who’d started out with him from Teddy’s had gotten too chickenshit and run. I heard the kids crying first, but George was the one who busted into the building and got the five of them out alive. Then, when your reporter got to him later, George made out like it was all me, because he didn’t want the acclaim, prestige, and attendant hero-worship. Which, in the mood I am now, I approve of. Now is George a bad man?”

“I believe—” the voice was dry—“implicit in what you originally asked was that so necessary distinction between those who do good and who are good.”

“Sure,” I said. “But explicit in what you said was that bit about making do with what you can get. I can get George if I need him. He’s genial enough for a god, with some nicely human failings like a history of lust.”

“I think I’m still Judeo-Christian enough to be uncomfortable with expressly human demiurges.”

“In the state-approved religion, the governor is God’s appointed representative on earth, if I remember right. Isn’t that, when all is said and done, what makes the relation between the head of the state and the head of the church as ticklish as you were just telling me it is? You’re as much a god as George, minus some celestial portents and—of course, I’m just guessing—a couple of inches on your dick.”

“I suppose one valid purpose of poets is to bring blasphemy to the steps of the altar. I just wish you hadn’t felt obliged to do it today. Nevertheless, I appreciate it as a political, if not a religious, necessity.”

“Mr. Calkins,” I said, “most of your subjects aren’t sure whether or not this place even exists. I’m not presenting any long considered protest. I wasn’t sure there was a Father till today. I was just asking—”

“What are you asking, young man?”

What I’d intended to come back with got cut away by my realization of his real distress. “Um…” I tried to think of something clever and couldn’t. “…is the Father a good man?”

When he didn’t answer, and I began to suspect/recall why, I wanted to laugh. Determined to go in silence, I got off the arm of the chair. Three steps, though, and my blubbering broke into a full throated giggle that threatened torrents. If Calkins could have seen, I would have flashed my lights.

Brother Randy, robes blowing about his sneakers, stepped around the corner. “You’re going?” He still wore his methadrine grimace.

“Um-hm.”

He turned to walk with me. The breeze that had been dull in my left ear now grew firm enough to beat my vest about my sides; it tugged Randy’s hood off. I looked at the lone Australia on the South Pacific of his skull. It wasn’t nearly as big as I’d imagined from the edge. He saw me looking; so I asked: “Does that hurt?”

“Sometimes. I think the dust and junk in the air irritate it. It’s a lot better now than it used to be. Before, it was all down over my ear and the back of my neck—when I first got here. The Father suggested I shave my head; that’s certainly given it a chance to heal.” We reached the steps. “The Father knows an awful lot about medicine. He’s made me put some stuff on it and it seems to be clearing up. I thought for a while he might have been a doctor or something, once, but I asked him…”

In the pause I nodded and started down. I’d swear he was on something, and the moment he’d started talking I’d gotten auditory visions of the endless rap.

“…and he said he wasn’t.

“So long.” He waved his big, translucent hand.

All the way across the broken overpass I tried to assemble what I had of the man behind the wall (my lights flashing through two flowered grills of stone, a web of light around his body); I even wondered what he felt during our conversation. The one thing that cleared when all my speculations fell away was that I had an urge to write. (Do you have that restless…? like it says in the back of the magazines. Sure.) But sitting here, in a back booth at Teddy’s, tonight, while Bunny does her number to not-quite-as-many-as-usual customers (I asked Pepper if he wanted to come with me but he really has this thing about going in here, so I brought my notebook for company), I see all it has produced is this account—and not what I wanted to work on. (Bunny lives in a dangerous world; she wants a good man. What she can get is Pepper…no, an image Pepper at his best [when he can smile] consents to give, but he’s usually too tired or ashamed to. Is it my place to tell her that, bringing my blasphemy to the altar steps, sharing with her the data from my noon journey? I just wish I enjoyed his dancing more.) This is not a poem. It is a very shabby report of something that happened in the year of Our Lord it would be oh-so-nice to write down, month, day, and year. But I can’t.

We didn’t say all those things in that way; but that is what we talked about. Reading it over brings back the reality of it for me. Would it for him? Or have I left out the particular, personal emblems by which he would recall and know it?

If Dollar doesn’t stop pestering Copperhead, then Copperhead will kill him. If Dollar stops pestering Copperhead, then Copperhead will let him alone. If Copperhead is going to kill Dollar, then Dollar will not have stopped pestering Copperhead. If Copperhead lets Dollar alone, then Dollar will have stopped pestering Copperhead. Which of the above is true? The one with the fewest words, of course. But that’s faulty logic. Why? Three times blessed is the Lord of Divine Words, the God of Thieves, the Master of the Underworld, dual sexed in character, double dealing in nature, yet one through all diffraction.

her elbow across his jaw.

John said, “Hey…!” and went back, hands up, palms out.

The sound she made was something I’d never heard out of anybody. She kicked at his leg, got him under the knee. He grabbed at her arm again but it wasn’t there, so he pulled back.

And stumbled over a root, right up against the trunk. Which made him really mad: he swung at her again.

She jumped. Straight up. His fist landed against her arm. She came down raking at his neck. His shirt tore.

He hit her, hard. But it didn’t matter; I thought she was going to bite his throat out. She bit something. He hissed, “Shit…!”

Denny grabbed my arm. “Hey, don’t you wanna stop her…?”

“No,” I said. I was scared to death.

John tried to punch her in the stomach.

Both of them twisted, missing.

Milly kept circling around them and Jommy started to say, “Hey, somebody…” and then saw the rest of us and just swallowed.

John pushed her away in the face. She grabbed his arm and yanked. Not pulled, yanked. His elbow hit the tree. He yelled, and hit her flat-handed in the jaw.

“FUCKER…!” she shouted so loud you knew it hurt her throat. “FUCKER…!”

Her right fist came down from her left ear and hammered his face. Like an echo his head cracked back against the trunk.

“Hey! Stop it…Stop…” Then I guess he really tried to break out. He shouted, grabbed her wrist…

She was meat red from the neck up, yanking her fist over, twisting his fingers; then grabbed one fist with the other and swung it against his neck.

“Jesus…” Jommy said, to me I realized. “She’s crazy…” But he stepped back from the look I gave him.

John tried to grab her in some sort of bear hug. He kicked out, and they both went down, him pretty much on top. Everyone stepped back together.

Flailing out, she came up with a handful of grass. Then there was grass in his hair and he yelled again.

His ear was bleeding. But I don’t know what she’d done.

“Hey, look!” Milly said, loud and upset. “Why doesn’t somebody…” Then it struck her that if somebody was, the somebody was going to have to be her.

She started forward.

I touched her on the shoulder and she looked sharply around.

“Fair fight,” I said.

He hit her three times, hard, one after the other: “Stupid. Bitch. Stupid…” but she somehow got him off. And reared back. She came down with both fists on his face, once glancing off his ear and hitting the ground and coming up for another hit, bloody. When she hit him again—he was just trying to cover his face, now—I saw hers was scraped up bad.

About the sixth time she hit him—one knee went into his stomach—I thought maybe I should try and stop her. I thought about Dollar. I thought about Nightmare and Dragon Lady. But I wasn’t as scared as I’d been at the beginning, when I’d thought her quivering, shaking rage would explode her.

Denny’s mouth was open. He let go my arm.

She stood up, almost falling. “You fucking shit!” she said. It sounded like her jaw clicked between syllables. She kicked him in the head. Twice.

“Hey, come on…” one of the others said, and started toward her. But didn’t touch her.

Thinking: Maybe a tennis sneaker isn’t that hard.

Sure.

She turned and came, blindly, toward me.

As Denny fell back, she stopped, looked behind her and shouted, “You fucking shit!” and came on. Her face was all puffed on one side.

Two of the guys kneeled beside John. Milly hovered behind them as though she still couldn’t make up her mind.

“Oh, wow!” Denny said. “You really creamed the bastard!”

“The fucking shit!” she whispered, wiping at her face and grimacing. “The fucking…” One eye was all teary. She started walking. We walked with her.

“It looks like he got in a couple too,” Denny said.

“She’s walking,” I said.

“Hey, you did better than Glass did with Dollar,” Denny said.

“I had—” She took a breath. “I guess I had more reason.” She rubbed her shoulder with her palm, fingers strained wide. And left blood on the workshirt sleeve. I don’t think she knew she was bleeding yet.

“Hey, Lanya?” Jack said. Frank stood behind his shoulder.

She stopped and looked.

She swallowed and I wondered if she remembered who he was.

I was probably projecting.

“Thanks,” Jack said.

She nodded, swallowed once more, and started walking again.

“What’s the matter?” Denny asked about twenty yards later. “Your eye hurt?”

She shook her head. “It’s just that…” She really sounded upset. “Well, nice girls from Sarah Lawrence don’t usually beat the fucking shit out of…” and gasped again.

I put my arm around her shoulder. She fitted like usual. Only she didn’t adjust her step to mine. So I adjusted mine to hers. “Did you want me to lend you a hand in there?”

“I would have pulled your balls off!” she said. “I would have…I don’t know what I would have…”

I squeezed her shoulder. “Just asking, babes.”

She touched her jaw again, gently, realizing it hurt. And left blood there. “The school was my thing. It wasn’t yours. You didn’t have anything to do with it. You didn’t even like Paul…Oh, the fucking shit—!” and stopped walking.

“I helped you with the class a couple of times,” Denny said. “Didn’t I?” and glanced back at the others.

“Sure,” Lanya said, and put her hand on his shoulder. Then she winced and reached down to rub her leg. Not limping, she still favored it.

“I just don’t understand why you lit into him,” I said.

“Oh, fuck you!” She pulled away from me. “You don’t understand a lot of things. About me.”

“All right,” I said. “I’m sorry.”

“So am I,” she said, harshly. But when I caught up with her, she put her arm around my shoulder. And adjusted her step.

“Hey,” Denny said. “You wanna be by yourself for a while?”

“Yeah,” she said. “Yes I do.”

She walked with us to the park entrance, so that I figured she was going back with us to the nest. But by the lions she said, “I’ll see you later,” and just walked off.

“Hey…” I called.

“She wants to be by herself,” Denny said.

I still felt funny.

She did come back to the nest, late that night after we’d been in bed (me half drunk) about an hour. Vaguely I heard her taking off her clothes, then climbing the ladder pole.

She crawled across me, rolled me by the shoulder onto my back, and, a-straddle my chest, glared down, swaying like she was going to rip something out of me with her teeth. I reached between her legs and pushed two fingers through her hair between the granular walls; they wet.

She leaned both hands on my chest, her arms pushing her breasts together and actually growled.

Denny, wedged in the corner, turned over, lifted his head, and said, “Huh…?”

“You too!” she said. “You come here too!”

I’ve never been balled like that before—puffy eye and sore leg notwithstanding—by any one. (She said she’d spent the afternoon and evening with Madame Brown, just talking. “You ever ball her?” Denny wanted to know.) In the middle of a heavy stretch, Copperhead stuck his head over the edge of the loft and asked, “What are you guys doing up here anyway? You’re gonna tear the loft down!”

“Get out of here,” Denny said. “You had your chance.”

Copperhead grinned and got.

Walked around the streets this afternoon with Nightmare, listening to his reminiscences of Dragon Lady: “Man, we used to do some freaky things, all the time, any time, anywhere, right in the middle of the fuckin’ street, man, I swear.” We ambled; he pointed out doorways, alleys, a pickup truck parked on its axles—“Once with her sitting in the cab and me standing on the fuckin’ sidewalk, a hand on either side of the door, and my head just in there, eatin’ out all that black pussy—Baby and Adam running around someplace across the street—then I fucked her in the back there, on the burlap. Oh, shit!”—and where, by the park, she had pushed him up against the wall and blown him; where she used to make him walk down the center of the street with his genitals loose from his fly, “with her sitting on the curb and doing things with her mouth, man, before I even got there, so I had a hard-on out to here!” He talks out these celebrations as though they are religious rituals recently banned. Forty minutes of this, before it hit me how lonely not only Nightmare is, but all of us here are: Who can I discuss the mechanics of Lanya and Denny with? I don’t even have the consolation of public disapproval. He probably has never talked about any of this before. On the marble steps of the Second City Bank building (he tells me) he made her take off all her clothes—“Just like Baby, man. I mean people can go around in the street stark naked here, and it don’t mean nothing”—and urinate, while he stood behind her, one arm over her shoulder, catching her water in his palm. “And once she made me lie on my back, you know, in the center of the pavement—” the incident illustrated with much gesturing and head-shaking as we search his memories out of the dry mist—“naked, man, and she just walked around and around and around me, a big woman!” (He repeats this last a lot, as though her circling defined some terribly necessary boundary on this wild terrain.) “…made me eat her out for half an hour, I swear, right—” he looks around, surprised—“here, man. Right here! It was just getting light, and you couldn’t hardly see her…” As my attention drifted from his account, I thought of all the clichés about how to act among violent people, current among the non-violent: Rise to the first challenge or you’ll be branded a coward for the rest of your stay; a willingness to fight gains the group’s respect; once you beat him, the bully will be your friend. Somebody coming into the nest with these as functioning propositions would get killed! (Thinking: Frank?) Nightmare’s shoulders rocked. His fists, wrists bound in leather, bobbed. He recounted hoarsely: “She used to get me drunk and I’d have her suck me off, my ass up against any old, cold, God-damn wall, with my pants down around my fuckin’ knees, and her tryin’ to get two fingers up my ass—don’t remember how she figured out I like that.” Suddenly he looked up, frowning. “You think I was right?”

“Huh?”

“When we had that garden party back at the nest.” His meaty hand returned to the fresh scars down his arm. “You think I done right?”

“Dragon Lady is her own woman,” I said.

Nightmare asked: “What would you do if somebody pulled that shit on you?”

“I think,” I said, “I would have cut her head off. Just messing up her arm for a couple of weeks—well, you both showed great restraint.”

“Oh.” His hand, knotting, slid down his chest to knuckle his belly, pensively.

“But nobody has ever pulled that on me,” I said. “At least Dragon Lady hasn’t, yet. So I still dig you both.”

“Yeah,” Nightmare said. “Sure. I understand. But nobody would do you that way. They think you’re too smart. They think they can talk to you. Maybe that’s why I gave you the nest, you know?”

That surprised me.

“Yeah,” he went on, “like I said: It’s time for me to get out of this motherfuckin’ sad-assed excuse for a—”

Behind his voice, children’s voices: we were passing the curtained windows of Lanya’s school. Nightmare looked. The door was ajar on darkness; laughter, juvenile shrieks, and chatter…

I stepped up the curb over the gutter grate. Nightmare followed. I glanced back: his thick forehead skin creased in a squint; his lips pulled up and down from the whole (and one broken) teeth.

I stepped through the door.

On the table, above the empty chairs, spools glimmered and spun on the tape recorder. We watched awhile, waiting. Beside me, Nightmare mauled and kneaded his bald shoulder, listening to the recorded noise in the vacated room. Scars, chains, and office, some thrust away, some new received, habits without correlatives, jumbled in the great bag of him, as though his achievements and losses completed a design mapped in the layout of the streets around us. Thinking: I may never see this man again after today, if all

own eyes, for somewhere in this city is a character they call: The Kid. Age: ambiguous. Racial origin: same. True name: unknown. He lives among a group (whose alleged viciousness is only surpassed by their visible laziness) over which he holds a doubtful authority. They call themselves scorpions. He is the supposed author of a book that has been distributed widely in town. Since it is the only book in town, that it is the most discussed work of the season is a dubious distinction. That and the intriguing situation of the author tend to blur accurate assessment of its worth. I admit: I am intrigued.

Today I cut down the block where I’d heard the scorpions had their nest. “What kind of street do they live on?” In the grammar of another city, that sentence would hold the implication: What kind of street are they more or less constrained by society to live on, given their semi-outlaw status, their egregious manner and outfit, and the economics of their asocial position? In Bellona, however, the same words imply a complex freedom, a choice from hovel to mansion—complex because every hovel and every mansion sustains through that choice some remnant of our ineffable catastrophe: In any house here movement from room to room is a journey from a place where twin moons have cast double shadows of the windowsills upon the floors to a place where once, because the sun had grown so immense, no shadow was cast at all. We speak another language here. Is the real importance of this chapbook that I’ve been browsing over all morning that, unlike the newspaper, it is the only thing in the city written in this language? If it is the only thing said, by default it must be the best thing. Anyone sensitive to language, living in this mess/miasma, must applaud it. Is there any line in it, however, that would be comprehensible outside city limits?

Five were sitting on the steps. Two leaned against the wrecked car at the curb. Why am I surprised that most of them are black? The flower-children, whose slightly demonic heirs these are, were so emphatically

blond, and the occasional darky among them such an emphatic mark of tolerance! They were not sullen.

This remains with me from my last conversation with Tak about Calkins and the party: “I had the funniest dream last night, Kid. Not that I particularly care what it means—I interpret other peoples’ dreams and just try to enjoy my own. Anyway, I had this little black kid, about thirteen or fourteen, up at my place—Bobby? I think you were catching a nap there once when he came by. In the dream, he was just standing there in a T-shirt, with half a hard-on. (Half a hard-on on Bobby goes out to here!) Suddenly I looked up and George was coming across the roof toward the door, as though he’d just come up for a visit. When he stepped in, he saw us. All the posters of him across the wall, I think but I’m not sure, were staring at us too. And he had this sort of mocking look that said, ‘So that’s what you’re after.’ And I felt very guilty. Oh, the point of it was that in the dream Bobby and I weren’t going to have sex. He wanted to show me something on his cock—some sore or something. And I felt all uncomfortable, like I’d been trapped into being something that I’m not. I mean given my choice of types—types and not individuals—I’d rather have a Georgia farm-boy any day. Not that I’ve ever kicked Bobby out of bed. But it was a strange dream.”

My first reaction was that Tak, who had always seemed a pretty big man, became much smaller. Later I realized that the big man simply contained many components, among them a small one

There were three girls among them, one an ebullient young black girl, capped with a large natural and vastly pregnant. They wore chains, some as many as fifteen strands, some as few as two. They were dirty and gregarious. They smiled and talked a sort of quiet half-talk to one another. Boots, leather vests—no shirts—and chains made them look like some ’cycle club in Coventry. A tall, skinny, black boy on the top step had a gallon of wine between his boot heels which periodically passed on its way to the curb and back. The white guy with no vest and the scarred stomach was the only one who wiped the neck—with a hand so grubby the other colored girl, tall and hefty, refused to drink after him. The others laughed as if her rebuke contained more than was apparent. They did not look at me as I strolled on the other side of the street. It is rumored that these men and women can transform themselves in darkness to any one of a gallery of luminous beasts; that they have weapons to turn the slung fist into a five-way cutting tool. I wonder if anyone that I saw there was the Kid—

Also wonder if writing about myself in the third person is really the way to go about losing or making a name. My life here more and more resembles a book whose opening chapters, whose title even, suggest mysteries to be resolved only at closing. But as one reads along, one becomes more and more suspicious that the author has lost the thread of his argument, that the questions will never be resolved, or more upsetting, that the position of the characters will have so changed by the book’s end that the answers to the initial questions will have become trivial. (It is Troy, Sodom, Çatal Höyük, the City of Dreadful

It’s not light yet. (Will it ever be?) Just returned from the third and what I hope is the last run on the Emoboriki. Don’t even want to write about this one. But, as usual, will. (At least, he said and can you hear the cap’s, They Will Not Be Bothering Us Again. Tarzan’s bizarrely reflective comment [echoing something he heard from me?]: “It’s easier here than any place else.” Raven, Priest, Tarzan, and Jack the Ripper kept telling me, “Man don’t take Pepper along!”

“Anyone goes who wants to go,” I said. By the time we went, though, Pepper wasn’t around anyway. Dragon Lady was waiting for us in front of Thirteen’s; Baby, b. a. as usual, pimple-pocked and sullen, stood in the shadowed doorway. His arms slung through his chains, Adam sat on the curb, grumbling glumly. Cathedral, Revelation and Fireball and brought the cans of

an ocean of smoke and evening. I tried to smell it, but my nostrils were numb or acclimated. The lions gaped in the blurr. We neared the fogged pearl of one functioning lamp, and her face got all twisted. She stopped, turquoise, hem to knees, exploding high as her scarlet waist. “Should we…? Oh, Kid! Do you know what they said!”

“Will you please…” I asked her. My throat hurt with running and the raw air. “Will you please tell me what…what they said!”

Both hands came up to cage her mouth. She was a shower of silver on metallic black. “Someone, up on the roof of the bank: The Second City Bank—oh, a Goddamn sniper!”

“Who, for Christ’s sake?” I grabbed her small elbows and the hair shook around her head. “Will you tell me who they got?”

“Paul,” she whispered. “Paul Fenster! The school, Kid…everything!”

Woke up this morning in the dark loft. Heard a handful of cars before I rolled to the window and pulled back the shade. Sunlight opened like a fan across the blanket. I climbed down the ladder, pole, dressed, and went outside. The air was chill enough to see breath. The sky, lake blue, was fluffed with clouds to the south; the north was clear as water. I walked to the end of the block. The pavement was dark near the edge from pre-dawn rain. I stepped over a puddle. At the bus stop—was it eight o’clock yet?—stood a man in a quilted jacket carrying a black enamel lunch box; two women with fur collars; a man in a grey hat with a paper under his arm; one woman in red shoes with big, boxy heels. Across the street stood a longhaired kid in an army jacket, thumb out for the uphill traffic. He grinned at me, trying for my attention. I thought it was because I’d left one boot off, but he wanted me to look at something in the sky without attracting the other people at the stop. I looked up between the trolley wires. White clouds hung behind the downtown buildings, windows like a broken honey comb running with brass dawn-light. Perhaps twenty-five degrees of an arc, air-brushed on the sky, were the pink, the green, the purple of a rainbow. I looked back at the kid on the corner, but a seventy-five Buick came glistening to a stop for him and he was getting oh God oh Jesus, please oh please I can’t I please don’t let it