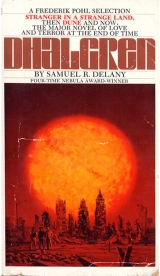

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“That’s how we met Tak,” John said. To Tak: “Isn’t it, Tak?”

Tak said: “He’s new.”

“Oh. Well,” John said, “we’ve got this thing going here. Do you want to explain it to him, Mildred?”

“Well, we figure—” Mildred’s shoulders came, officially, forward. “We figure we have to survive together some way. I mean we can’t be at each other’s throats like animals. And it would be so easy for a situation like this—” He was sure her gesture, at ‘this,’ included nothing beyond the firelight—“to degenerate into something…well, awful! So we’ve set up I guess you’d call it a commune. Here, in the park. People get food, work together, know they have some sort of protection. We try to be as organic as possible, but that’s getting harder and harder. When new people come into Bellona, they can get a chance to learn how things operate here. We don’t take in everybody. But when we do, we’re very accepting.” There was a tic somewhere (in him or her, he wasn’t sure, and started worrying about it) like a nick in a wire pulled over an edge. “You are new? We’re always glad when we get somebody new.”

He nodded, while his mind accelerated, trying to decide: him? her?

Tak said: “Show him around, Milly.”

John said: “Good idea, Mildred. Tak, I want to talk to you about something,” tapping his newspaper again. “Oh, here. Maybe you want to take a look at this?”

“What? Oh…” You couldn’t worry so much about things like that. Often, though, he had to remind himself. “Thanks.” He took the folded paper.

“All right, Tak.” John, with Tak, turned away. “Now when are you going to start those foundations for us? I can give you—”

“Look, John.” Tak put his hand on John’s shoulder as they wandered off. “All you need is the plans, and you can—”

Then they were out of earshot.

“Are you hungry?”

“No.” She was pretty.

“Well, if you are—come, let’s go over here—we start cooking breakfast soon as it gets light. That’s not too far off.”

“You been up all night?” he asked.

“No. But when you go to bed at sundown, you wake up pretty early.”

“I have.”

“We do a lot of work here—” she slipped her hands into her back pockets; her jeans, torn short, were bunched high on her thighs—“during the day. We don’t just sit around. John has a dozen projects going. It’s pretty hard to sleep with people hammering and building and what all.” She smiled.

“I’ve been up; but I’m not tired. When I am, I can sleep through anything.” He looked down at her legs.

As she walked, light along them closed and crossed. “Oh, we wouldn’t mind if you really wanted to sleep. We don’t want to force anybody. But we have to maintain some kind of pattern, you understand.”

“Yeah, I understand that.” He’d been flipping the newspaper against his own thigh. Now he raised it.

“Why do you go around wearing an orchid?” she asked. “Of course, with the city in the state it’s in, I guess it makes sense. And really, we do accept many life styles here. But…”

“Some people gave it to me.” He turned the rolled newspaper around.

SERIOUS WATER

He let the tabloid fall loose.

SHORTAGE THREATENS

The date said Tuesday, February 12, 1995. “What the hell is that?”

She looked concerned. “Well, there’s not very many people around who know how to keep things running. And we’ve all been expecting the water to become a real problem any day. You have no idea how much they used when they were trying to put out the fires.”

“I mean the 1995?”

“Oh. That’s just Calkins.” On the picnic table sat a carton of canned goods. “I think it’s amazing we have a newspaper at all.” She sat on the bench and looked at him expectantly. “The dates are just his little joke.”

“Oh.” He sat beside her. “Do you have tents here? Anything for shelter?” still thinking: 1995?

“Well, we’re pretty outdoors oriented.” She looked around, while he tried to feel the city beyond the leafy, fire-lit grotto. “Of course, Tak—he’s promised to give John some simple blueprints. For cabins. John wants Tak to head the whole project. He feels it would be good for him. You know, Tak is so strange. He feels, somehow, we won’t accept him. At least I think he does. He has this very important image of himself as a loner. He wants to give us the plans—he’s an engineer, you know—and let us carry them out. But the value of something like that isn’t just the house—or shack—that results. It should be a creative, internal thing for the builder. Don’t you think?”

For something to do, he held his teeth together, hard.

“You’re sure you’re not hungry?”

“Oh. No.”

“You’re not tired? You can get in a few hours if you want. Work doesn’t start till after breakfast. I can get you a blanket, if you’d like.”

“No.”

In the firelight, he thought he might count twenty-five years in her firm, clear face. “I’m not hungry. I’m not sleepy. I didn’t even know Tak was bringing me here.”

“It’s a very nice place. It really is. The community of feeling is so warm, if nothing else.” Probably only twenty.

The harmonica player played again.

Someone in an olive-drab cocoon twisted beyond the fire.

Mildred’s tennis sneaker was a foot from the nearest sleeper’s canvas covered head.

“I wish you wouldn’t wear that.” She laughed.

He opened his big fingers under metal.

“I mean, if you want to stay here. Maybe then you wouldn’t have to wear it.”

“I don’t have to wear it,” and decided to keep it on.

The harmonica squawked.

He looked up.

From the trees, light brighter than the fire and green lay leafy shadows over sleeping bags and blanket rolls. Then ballooning claws and barbed, translucent tail collapsed:

“Hey, you got that shit ready for us?”

A lot of chains hung around his neck. He had a wide scab (with smaller ones below it) on the bowl of his shoulder, like a bad fall on cement. Chains wound around one boot: He jingled when he walked. “Come on, come on. Bring me the fuckin’ junk!” He stopped by the fireplace. Flames burnished his large arms, his small face. A front tooth was broken. “Is that it?” He gestured bluntly toward the picnic table, brushed tangled, black hair, half braided, from his shoulder, and came on.

“Hello!” Mildred said, with the most amazing smile. “Nightmare! How have you been?”

The scorpion looked down at her, wet lip high off his broken tooth, and said, slowly, “Shit,” which could have meant a lot of things. He wedged between them—“Get out of the—” saw the orchid—“fucking way, huh?” and lugged the carton of canned goods off the table edge against his belly, where ripe, wrinkled jeans had sagged so low you could see stomach hair thicken toward pubic. He looked down over his thick arm at the weapon, closed his mouth, shook his head. “Shit,” again, and: “What the fuck you staring at?” Between the flaps of Nightmare’s cut-down vest, prisms, mirrors, and lenses glittered among dark cycle chain, bright stainless links, and hardware-store brass.

“Nothing.”

Nightmare sucked his teeth in disgust, turned, and stumbled on a sleeping bag. “Move, damn it!”

A head shook loose from the canvas; it was an older man, who started digging under the glasses he’d probably worn to sleep, then gazed after the scorpion lumbering off among the trees.

He saw things move behind Milly’s face, was momentarily sure she was going to call good-bye. Her tennis shoe dragged the ground.

Down her lower leg was a scratch.

He frowned.

She said: “That was Nightmare. Do you know about the scorpions?”

“Tak told me some.”

“It’s amazing how well you can get along with people if you’re just nice. Of course their idea of being nice back is a little odd. They used to volunteer to beat up people for us. They kept wanting John to find somebody for them to work over—somebody who was annoying us, of course. Only nobody was.” She hunched her shoulders.

“I guess,” he offered from the faulted structure of his smile, “you have trouble with them sometimes?”

“Sometimes.” Her smile was perfect. “I just wish John had been here. John’s very good with them. I think Nightmare is a little afraid of John, you know? We do a lot for them. Share our food with them. I think they get a lot from us. If they’d just acknowledge their need, though, they’d be so much easier to help.”

The harmonica was silent: the bare-breasted girl had gone from her blanket.

“How’d you get that scratch?”

“Just an accident. With John.” She shrugged. “From one of those, actually.” She nodded toward his orchid. “It isn’t anything.”

He leaned to touch it, looked at her: She hadn’t moved. So he lay his forefinger on her shin, moved it down. The scab line ran under his callous like a tiny rasp.

She frowned. “It really isn’t anything.” Framed in heavy red, it was a gentle frown. “What’s that?” She pointed. “Around your wrist.”

His cuff had pulled up when he’d leaned.

He shrugged. Confusion was like struggling to find the proper way to sit inside his skin. “Something I found.” He wondered if she heard the question mark on his sentence, small as a period.

Her eyebrow’s movement said she had: which amused him.

The optical glass flamed over his knobby wrist.

“Where do you get it? I’ve seen several people wear that…kind of chain.”

He nodded. “I just found it.”

“Where?” Her gentle smile urged.

“Where did you get your scratch?”

Still smiling, she returned a bewildered look.

He had expected it. And he mistrusted it. “I…” and the thought resolved some internal cadence: “want to know about you!” He was suddenly and astonishingly happy. “Have you been here long? Where are you from? Mildred? Mildred what? Why did you come here? How long are you going to stay? Do you like Japanese food? Poetry?” He laughed. “Silence? Water? Someone saying your name?”

“Um…” He saw she was immensely pleased. “Mildred Fabian, and people do call me Milly, like Tak does. John just feels he has to be formal when new people come around. I was here at State University. But I come from Ohio…Euclid, Ohio?”

He nodded again.

“But State’s got such a damned good poli-sci department. Had, anyway. So I came here. And…” She dropped her eyes (brown, he realized with a half-second memory, as he looked at her lowered, corn-colored lashes—brown with a coppery backing, copper like her hair) “…I stayed.”

“You were here when it happened?”

“…yes.” He heard a question mark there bigger than any in the type-box.

“What…” and when he said, “…happened?” he didn’t want an answer.

Her eyes widened, dropped again; her shoulders sank; her back rounded. She reached toward his hand in its cage, lying between them on the bench.

As she took a shiny blade tip between two fingers, he was aware of his palm’s suspension in its harness.

“Does…I’ve always…well, could you make an…” She tugged the point to the side (he felt the pressure on his wrist and stiffened his hand), released it: A muffled Dmmmmm. “Oh.”

He was puzzled.

“I was wondering,” she explained, “if you could make it ring. Like an instrument. All the blades are different lengths. I thought if they made notes, perhaps you could…play them.”

“Blade steel? I don’t think it’s brittle enough. Bells and things are iron.”

She bent her head to the side.

“Things have to be brittle if they’re going to ring. Like glass. Knives are hard, sure; but they’re too flexible.”

She looked up after a moment. “I like music. I was going to major in music. At State. But the poli-sci department was so good. I don’t think I’ve seen one Japanese restaurant in Bellona, since I’ve been in school here. But there used to be several good Chinese ones…” Something happened in her face, a loosening, part exhaustion, part despair. “We’re doing the best we can, you know…?”

“What?”

“We’re doing the best we can. Here.”

He nodded a small nod.

“When it happened,” she said softly, “it was terrible.” “Terrible” was perfectly flat, the way he remembered a man in a brown suit once say “elevator.” It’s that tone, he thought, remembering when it had denuded Tak’s speech. She said: “We stayed. I stayed. I guess I felt I had to stay. I don’t know how long…I mean, I’m going to stay for. But we have to do something. Since we’re here, we have to.” She took a breath. A muscle leaped in her jaw. “You…?”

“Me what?”

“What do you like, Kidd? Someone saying your name?”

He knew it was innocent; and was annoyed anyway. His lips began a Well, but only breath came.

“Silence?”

Breath became a hiss; the hiss became, “…sometimes.”

“Who are you? Where are you from?”

He hesitated, and watched her eyes pick something from it:

“You’re afraid because you’re new here…I think. I’m afraid, I think, because I’ve been here…an awfully long time!” She looked around the campsite.

Two long-haired youngsters stood by the cinderblocks. One held up his hands, either to warm them, or just to feel heat.

It is a warm morning. I do not recognize any protection in this leafy blister. There is no articulation in the juncture of object and shadow, no fixed angle between fuel and flame. Where would they put their shelters, foundations sunk on ash; doors and windows sinking in cinders? There is nothing else to trust but what warms.

Mildred’s lips parted, her eyes narrowed. “You know what John did? I think it was brave, too. We had just finished building that fireplace; there were only a few of us here, then. Somebody was going to light it with a cigarette lighter. But John said, wait; then went off all the way to Holland Lake. That was when the burning was much worse than it is now. And he brought back a brand—an old, dried, burning stick. In fact he had to transfer the fire to several other sticks on the way back. And with that fire—” she nodded where one of the youngsters was now poking at the logs with a broken broom-handle—“he lit ours.” The other waited with a chunk of wood in his arms. “I think that was very brave. Don’t you?” The chunk fell. Sparks geysered through the grate, higher than the lowest branches.

“Hey, Milly!”

Sparks whirled, and he wondered why they all spoke so loud with so many sleeping.

“Milly! Look what I found.”

She had put on a blue workshirt, still unbuttoned. In one hand was her harmonica, in the other a spiral notebook.

“What is it?” Milly called back.

As she passed the furnace, she swung the notebook through the sparks; they whipped into Catherine wheels, and sank. “Does it belong to anybody around here? It’s burned. On the cover.”

She sat with it, between them, shoulders hunched, face in a concentrated scowl. “It’s somebody’s exercise book.” The cardboard was flaky black at one corner. Heat had stained half the back.

“What’s in it?” Milly asked.

She shrugged. Her shoulder and her hip moved on his. He slid down the bench to give her room, considered sliding back, but, instead, picked up the newspaper and opened it—blades tore one side—to the second page.

“Who ripped out the first pages?” Milly asked.

“That’s the way I found it.”

“But you can see the torn edges, still inside the wire.”

“Neat handwriting.”

“Can you make out what it says?”

“Not in this light. I read some down by the park lamp. Let’s take it over by the fire.”

The page he stared at flickered with backlight, the print on both sides visible. All he could make out was the Gothic masthead:

BELLONA TIMES

And below it:

ROGER CALKINS.

Editor and Publisher.

He closed the paper.

The girls had gone to the fireplace.

He stood, left the paper on the bench, stepped, one after another, over three sleeping bags and a blanket roll. “What does it say?”

Her harmonica was still in one fist.

Her hair was short and thick. Her eyes, when she looked at him directly, were Kelly green. Propping the book on the crook of her arm, with her free hand she turned back the cardboard cover for him to see the first page. Remnants of green polish flecked her nails.

In Palmer-perfect script, an interrupted sentence took up on the top line:

to wound the autumnal city.

So howled out for the world to give him a name.

That made goose bumps on his flanks…

The in-dark answered with wind.

All you know I know: careening astronauts and bank clerks glancing at the clock before lunch; actresses cowling at light-ringed mirrors and freight elevator operators grinding a thumbful of grease on a steel handle; student

She lowered the notebook to stare at him, blinked green eyes. Hair wisps shook shadow splinters on her cheek. “What’s the matter with you?”

His face tensed toward a smile. “That’s just some…well, pretty weird stuff!”

“What’s weird about it?” She closed the cover. “You got the strangest look.”

“I don’t…But…” His smile did not feel right. What was there to dislodge it lay at the third point of a triangle whose base vertices were recognition and incomprehension. “Only it was so…” No, start again. “But it was so…I know a lot about astronauts, I mean. I used to look up the satellite schedules and go out at night and watch for them. And I used to have a friend who was a bank clerk.”

“I knew somebody who used to work in a bank,” Milly said. Then, to the other girl: “Didn’t you ever?”

He said: “And I used to have a job in a theater. It was on the second floor and we always had to carry things up in the freight elevator…” These memories were so simple to retrieve…“I was thinking about him—the elevator operator—earlier tonight.”

They still looked puzzled.

“It was just very familiar.”

“Well, yeah…” She moved her thumb over the bright harmonica. “I must have been on a freight elevator, at least once. Hell, I was in a school play and there were lights around the dressing room mirror. That doesn’t make it weird.”

“But the part about the student riots. And the bodegas…I just came up from Mexico.”

“It doesn’t say anything about student riots.”

“Yes it does. I was in a student riot once. I’ll show you.” He reached for the book (she pulled back sharply from the orchid), spread his free hand on the page (she came forward again, her shoulder brushing his arm. He could see her breast inside her unbuttoned shirt. Yeah) and read aloud:

“‘…thumbful of grease on a steel handle; student happenings with spaghetti filled Volkswagens, dawn in Seattle, automated evening in L.A.’” He looked up, confused.

“You’ve been in Seattle and Los Angeles, morning and night, too?” Her green-eyed smile flickered beside the flames.

“No…” He shook his head.

“I have. It’s still not weird.” Still flickering, she frowned at his frown. “It’s not about you. Unless you dropped it in the park…You didn’t write it, did you?”

“No,” he said. “No. I didn’t.” Lost (it had been stronger and stranger than any déjà vu), the feeling harassed him. “But I could have sworn I knew…” The fire felt hottest through the hole at his knee; he reached down to scratch; blades snagged raveled threads. He snatched the orchid away: Threads popped. Using his other hand, he mauled his patella with horny fingers.

Milly had taken the book, turned a later page.

The green-eyed girl leaned over her shoulder.

“Read that part near the end, about the lightning and the explosions and the riot and all. Do you think he was writing about what happened here—to Bellona, I mean?”

“Read that part at the beginning, about the scorpions and the trapped children. What do you suppose he was writing about there?”

They bent together in firelight.

He felt discomfort and looked around the clearing.

Tak stepped over a sleeping bag and said to John: “You people want me to work too hard. You just refuse to understand that work for its own sake is something I see no virtue in at all.”

“Aw, come on, Tak.” John beat his hand absently against his thigh as though he still held the rolled paper.

“I’ll give you the plans. You can do what you want with them. Hey, Kid, how’s it going?” Flames bruised Tak’s bulky jaw, prised his pale eyes into the light, flickered on his leather visor. “You doing all right?”

He swallowed, which clamped his teeth; so his nod was stiffer than he’d intended.

“Tak, you are going to head the shelter building project for us…?” John’s glasses flashed.

“Shit,” Tak said, recalling Nightmare.

“Oh, Tak…” Milly shook her head.

“I’ve been arguing with him all night,” John said. “Hey.” He looked over at the picnic table. “Did Nightmare come by for the stuff?”

“Yep.” Brightly.

“How is he?”

She shrugged—less bright.

He heard the harmonica, looked:

Back on her blanket, the other girl bent over her mouth harp. Her hair was a casque of stained bronze around her lowered face. Her shirt had slipped from one sharp shoulder. Frowning, she beat the mouth holes on her palm once more. The notebook lay against her knee.

“Tak and me were up looking at the place I want to put the shelters. You know, up on the rocks?”

“You’ve changed the location again?” Milly asked.

“Yeah,” Tak said. “He has. How do you like it around here, Kid? It’s a good place, huh?”

“We’d be happy to have you,” John said. “We’re always happy to have new people. We have a lot of work to do; we need all the willing hands we can get.” His tapping palm clove to his thigh, stayed.

He grunted, to shake something loose in his throat. “I think I’m going to wander on.”

“Oh…” Milly sounded disappointed.

“Come on. Stay for breakfast.” John sounded eager. “Then try out one of our work projects. See which one you like. You don’t know what you’re gonna find in ’em.”

“Thanks,” he said, “I’m gonna go…”

“I’ll take him back down to the avenue,” Tak said. “Okay, so long, you guys.”

“If you change your mind,” Milly called (John was beating his leg again), “you can always come back. You might want to in a couple of days. Just come. We’ll be glad to have you then, too.”

On the concrete path, he said to Tak: “They’re really good people, huh? I just guess I…” He shrugged.

Tak grunted: “Yeah.”

“The scorpions—is that some sort of protection racket they make the people in the commune pay?”

“You could call it that. But then, they get protected.”

“Against anything else except scorpions?”

Tak grunted again, hoarsely.

He recognized it for laughter. “I just don’t want to get into anything like that. At least not on that side.”

“I’ll take you back down to the avenue, Kid. It goes on up into the city. The stores right around here have been pretty well stripped of food. But you never know what you’re gonna luck out on. Frankly, though, I think you’ll do better in houses. But there you take your chances: Somebody just may be waiting for you with a shotgun. Like I say, there’s maybe a thousand left out of a city of two million: Only one out of a hundred homes should be occupied—not bad odds. Only I come near walking in on a couple of shotguns myself. Then you got your scorpions to worry about…John’s group?” The hoarse, gravelly laughter had a drunken quality the rest of Tak’s behavior belied. “I like them. But I wouldn’t want to stick around them too much either. I don’t. But I give them a hand. And it’s not a bad place to get your bearings from…for a day or two.”

“No. I guess not…” But it was a mulling “no.”

Tak nodded in mute agreement.

This park is alive with darknesses, textures of silence. Tak’s boot heels tattoo the way. I can envision a dotted line left after him. And someone might pick the night up by its edge, tear it along the perforations, crumple it, and toss it away.

Only two out of forty-some park lights (he’d started counting) were working. The night’s overcast masked all hint of dawn. At the next working light, within sight of the lion-flanked entrance, Tak took his hands out of his pockets. Two pinheads of light pricked the darkness somewhere above his sandy upper lip. “If you want—you can come back to my place…?”

5

“…OKAY”

Tak let out a breath—“Good—” and turned. His face went completely black. “This way.”

He followed the zipper jingles with a staggering lope. Boughs, black over the path, suddenly pulled from a sky gone grey inside a V of receding rooftops.

As they paused by the lions, looking down a wide street, Tak rubbed himself inside his jacket. “Guess we’re about to get into morning.”

“Which way does the sun come up?”

Loufer chuckled. “I know you won’t believe this—” they walked again—“but when I first got here, I could have sworn the light always started over there.” As they stepped from the curb, he nodded to the left. “But like you can see, today it’s getting light—” he gestured in front of them—“there.”

“Because the season’s changing?”

“I don’t think it’s changed that much. But maybe.” Tak lowered his head and smiled. “Then again, maybe I just wasn’t paying attention.”

“Which way is east?”

“That’s where it’s getting light.” Tak nodded ahead. “But what do you do if it gets light in a different place tomorrow?”

“Come on. You could tell by the stars.”

“You saw how the sky was. It’s been like that or worse every night. And day. I haven’t seen stars since I’ve been here—moons or suns either.”

“Yeah, but—”

“I’ve thought, maybe: It’s not the season that changes. It’s us. The whole city shifts, turns, rearranges itself. All the time. And rearranges us…” He laughed. “Hey, I’m pulling your leg, Kid. Come on.” Tak rubbed his stomach again. “You take it all too seriously.” Stepping up the curb, Tak pushed his hands into his leather pockets. “But I’m damned if I wouldn’t have sworn morning used to start over there.” Again he nodded, with pursed lips. “All that means is I wasn’t paying attention, doesn’t it?” At the next corner he asked: “What were you in a mental hospital for?”

“Depression. But it was a long time ago.”

“Yeah?”

“I was hearing voices; afraid to go out; I couldn’t remember things; some hallucinations—the whole bit. It was right after I finished my first year of college. When I was nineteen. I used to drink a lot, too.”

“What did the voices say?”

He shrugged. “Nothing. Singing…a lot, but in some other language. And calling to me. It wasn’t like you’d hear a real voice—”

“It was inside your head?”

“Sometimes. When it was singing. But there’d be a real sound, like a car starting, or maybe somebody would close a door in another room: and you’d think somebody had called your name at the same time. Only they hadn’t. Then, sometimes you’d think it was just in your mind when somebody had; and not answer. When you’d find out, you’d feel all uncomfortable.”

“I bet you would.”

“Actually, I felt uncomfortable about all the time…But, really, that was years back.”

“What did the voices call you—when they called?”

At the middle of the next block, Tak said:

“Just thought it might work. If I snuck up on it.”

“Sorry.” The clumsiness and sincerity of Tak’s amateur therapy made him chuckle. “Not that way.”

“Got any idea why it happened? I mean why you got—depressed, and went into the hospital in the first place?”

“Sure. When I got out of high school, upstate, I had to work for a year before I could go into college. My parents didn’t have any money. My mother was a full Cherokee…though it would have been worth my life to tell those kids back in the park, the way everybody goes on about Indians today. She died when I was about fourteen. I’d applied to Columbia, in New York City. I had to have a special interview because even though my marks in high school were good, they weren’t great. I’d come down to the city and gotten a job in an art supply house—that impressed hell out of them at the interview. So they dug up this special scholarship. At the end of the first term I had all B’s and one D—in linguistics. By the end of the second term, though, I didn’t know what was going to happen the next year. I mean about money. I couldn’t do anything at Columbia except go to school. They’ve got all sorts of extracurricular stuff, and it costs. If that D had been an A, I might have gotten another scholarship. But it wasn’t. And like I said, I really used to drink. You wouldn’t believe a nineteen-year-old could drink like that. Much less drink and get anything done. Just before finals I had a breakdown. I wouldn’t go outside. I was scared to see people. I nearly killed myself a couple of times. I don’t mean suicide. Just with stupid things. Like climbing out on the window ledge when I was really drunk. And once I knocked a radio into a sink full of dishwater. Like that.” He took a breath “It was a long time ago. None of that stuff bothers me, really, anymore.”

“You Catholic?”

“Naw. Dad was a little ballsy, blue-eyed Georgia Methodist—” that memory’s vividness surprised him too—“when he was anything. We never lived down south, though. He was in the Air Force most of the time when I was a kid. Then he flew private planes for about a year. After that he didn’t do much of anything. But that was after Mom died…”

“Funny.” Tak shook his head in self-reproach. “The way you just assume all the small, dark-complected brothers are Catholic. Brought up a Lutheran, myself. What’d you do after the hospital?”

“Worked upstate for a while. DVR—Division of Vocational Rehabilitation—was going to help me get back in school, soon as I got out of Hillside. But I didn’t want to. Took a joyride with a friend once that ended up with me spending most of a year cutting trees in Oregon. In Oakland I worked as a grip in a theater. Wasn’t I telling you about…No, that was the girl in the park. I traveled a lot; worked on boats. I tried school a couple more times, just on my own—once, in Kansas, for a year, where I had a job as a super for a student building. Then again in Delaware.”

“How far on did you get?”

“Did fine the first term, each place. Fucked up the second. I didn’t have another breakdown or anything. I didn’t even drink. I just fucked up. I don’t fuck up on jobs, though. Just school. I work. I travel. I read a lot. Then I travel some more: Japan. Down to Australia—though that didn’t come out too well. Bumming boats down around Mexico and Central America.” He laughed. “So you see, I’m not a nut. Not a real one, anyway. I haven’t been a real nut in a long time.”

“You’re here, aren’t you?” Tak’s Germanic face (with its oddly Negroid nose) mocked gently. “And you don’t know who you are.”

“Yeah, but that’s just ’cause I can’t remember my—”

“Home again, home again.” Tak turned into a doorway and mounted the wooden steps; he looked back just before he reached the top one. “Come on.”

There was no lamppost on either corner.

At the end of the block, a car had overturned in a splatter of glass. Nearer, two trucks sat on wheelless hubs—a Ford pickup and a GM cab—windshields and windows smashed. Across the street, above the loading porch, the butcher hooks swung gently on their awning tracks.