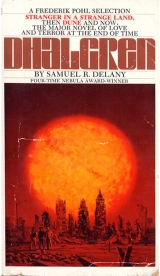

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 58 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“I know that,” I said. “I remember that. What’s your last name?”

He raised his head a little. His smile—a dragon, bobbing by, stained his face a momentary green—tightened: “You tell me yours, I’ll tell you mine.” His mouth stayed a little open, waiting for a laugh to come out.

But the laugh came from me. William…? I shouted: “I know who you are!” and doubled with hysteria. “I know…!”

“Hey, Kid? Come on now…” Lanya—she and Denny had followed me—took my arm again. I tried to pull away, stumbled into the dancers’ chains, and turned, flailing my own. But she held on; Denny had me too. I yanked once more and fell against a guy I didn’t know who cried, “Owwww!” and hugged me, laughing. I turned in a shield’s glare, bright blind a moment, and moments after images pulsed everywhere.

“Come on, man,” Denny kept saying, pulling at my forearm. “Watch out—” and held up a strand of chain so I could get under.

“That’s right,” Lanya said. “This way…”

I got dizzy and nearly fell. Fire and branches wheeled on a black sky. I came up against bark and turned my back to it:

“But I know what his name is! It has to be. He couldn’t be anybody else!” I kept telling them, then breaking off into a giggle which, when I let it go, twisted my face in a grin so huge my jaw muscles hurt and I had to rub them with the heels of my palms. “That’s got to be who he is! You understand why, don’t you? I mean you do understand?”

They didn’t.

But, for a while, I did.

And, bursting with my new knowledge, I danced.

I’ve never had more fun.

Then I came back and sat with them.

Denny’s hand was on my knee; Lanya’s shoulder was against my shoulder, her arm along my arm. We sat on the roots, ten feet from the high, forking fire, watching the men and women jog and jump to the sounds of their own bodies, one arched and beating the backs of his thighs, one spinning slowly, and shouting loudly, each time her short hair brushed by the sagging branch. Somebody danced with his belt loose and swinging. And somebody else was taking off her jeans.

Bill, arms folded across his black sweater, among the other watchers, watched.

I sat and panted and smiled (sweat dribbling the small of my back) with contentment over the absolute fact of his revealed identity, till even that, as all absolutes must, began its dissolve.

“What—?” Denny moved his hand on my leg.

Lanya glanced at me, shifted her shoulder against mine.

But I sat back again, silent, marveling the dissolve’s completion, both elated and numbed by the jarring claps that measured and metronomed each differential in the change—till I had no more certainty of Bill’s last name than I had of my own. With only the memory of knowledge, and bewilderment at whatever mechanic had, for minutes, made that knowledge as certain to me as my own existence, I sat, trying to sort that mechanism’s failure, which had let it slip away.

Dragon Lady, with her boot, shoved in another part of the furnace’s cinderblock wall, then turned to add her raucous contention to the argument behind her.

“You know,” Lanya said, as somebody flung a burning brand that landed on the edge of the dish, flame end on the grass, “this place isn’t going to be here tomorrow.”

“That’s all right,” Denny said.

Lanya pushed back against me harder, drew up her knees to hug.

The dance was all around us. The battered grass was tangled with chains, plain and jeweled. Most of the scorpions blazed up, incendiary—

up to bring the brandy, that afternoon, to Tak’s place—I apologized about opening one of the bottles—he really looked surprised.

He came out of the shed doorway onto the roof, scratching his chest and his chin and still half asleep. But saying he was glad to see us.

Denny climbed onto the balustrade to walk, hands out for balance, along the roof’s edge. Lanya kept running up and going, “Boo!” at him as though she were trying to make him fall off. I thought it was funny, but Tak said please stop it because it was eight stories down and scaring him into a stomach ache.

So they came back to the shack.

Denny went inside: “Look what Tak’s got on the wall!”

Thought he meant George, but it was the interview with me from Calkins’ party in the Times. Tak had stapled it to the wall just inside the door. The edges were yellow.

“I keep that there,” Tak said, “for inspiration. I sort of like it. Glad to see, after all this, the papers says you’re having another book.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Sure. Thanks.” I really didn’t want to talk about it. It got across, because he was looking at me a little sideways. But Tak is good at picking up on things like that.

Around us, the sky was close as crumpled lead. The first stanchion of the bridge was just visible through it, like a single wing of some dim bird that might, in a moment, fly anywhere.

Tak pulled the cork out of the open bottle. “Come on. Let’s have a drink.” He squatted, his back against the shack wall. We sat next to him. Denny took a swallow, screwed up his face, and from then on just passed it between Lanya and me.

“Tak,” I said, “could you tell me something?” I asked him about the bubbles around the inside of the glasses. “I thought it might have something to do with the water pressure for the city. Maybe it’s going down and that causes the ring to start higher?”

“I think,” Tak said to the green-glass neck, “it has more to do with who washes your dishes. You’re washing out a glass, see, and you run your finger around the inside to get off the crud, and it leaves this thin coating. But your finger doesn’t reach the bottom. Later you put water in the glass, and the air comes out of solution to form bubbles. But the bubbles need something to nucleate on. So the imperfections in the glass and the crud left above the grease line are easier to nucleate on; so you get this definite cutoff—”

“You mean,” I said, “the dishwasher sticks his finger less and less far down the glass every day?”

Tak laughed and nodded “Aren’t you glad you know some one with some idea of technology? Rising water tables, lowering pressure. You could get paranoid over stuff like that if you don’t know what you’re doing.”

“Yeah,” and I took the bottle and drank.

here any longer.

Curiosity took me, alone.

A bed had been overturned against the door but fell back clattering as soon as I pushed it in. They’d put bars up on the ground floor windows, but the panes were mostly smashed, and, in the one remaining, I found three of those tiny, multi-haloed holes you get from bullets. There were a couple of sleeping bags still around. Some nice stuff was up on the walls from where they had the place decorated: and a big, almost life-size lion wedged together out of scrap car-parts and junked iron. An acetylene bomb and nozzle leaned in the corner. (“I wonder what happened to the woman who was making that. She was Eurasian,” Lanya said when I told her about it, later. “She was a pretty incredible person; I mean even besides building that thing.”) The walls of two rooms were charred black. I saw a place where a poster had been burned away. And another place, where a quarter of one was left: George in the night wilderness. Upstairs I guess most of the rooms had never had doors. It was a wreck. Great pieces of plaster had been tugged off the walls. Once I heard what I thought was moaning, but when I rushed into the smashed up room—tools were scattered all over the floor, screwdrivers, nails, pliers, wrenches—it wasn’t a creaking shutter or anything. I don’t know what it was. Bolted to the wall was a plank on which they had carved their initials, names, phrases, some written in fancy combinations of colored magic markers, others scrawled in plank pen-tel. Near the bottom, cut clearly with some small blade: June R. Lanya says she’ll have to find some abandoned drugstore or someplace to get birth control pills now, in the next three months. Denny is worried about his little girlfriend. He says she was sick the last time he was over there, “…with a fever, man. And every thing. She wouldn’t hardly move, under the blankets.” No one at the commune, or the bar, or the church—neither George nor Reverend Amy—knows where they all went or even what really happened. But if someone would do that to the House, I just wonder about the nest. Was the blond girl they described June? I guess I hope so.

And over the next fifteen seconds, the afternoon sky, dull as an aluminum pot bottom, darkened to full night.

Five seconds into the darkening, Denny said, “Jesus, what—?” and stood up.

There was a noise like a plane coming. It kept coming too, while I watched Denny’s features go night blue.

Lanya grabbed my arm, and I turned to see her blue face, and all around it, go black.

If it was a plane, it was going to crash into us.

I jerked my head around left and right and up (hit the back of my head on the wall) and down, trying to see.

Another sound, under the roar, beside me: Tak standing?

Something wet my hand on the tarpaper beside me. He must have kicked over the brandy.

White light suddenly blotched the horizon, cut by the silhouette of a water tower.

I didn’t feel scared, but my heart was beating so slow and hard my chin jerked, each thump.

Light wound up the sky.

I could just see Tak standing now, beside me. His shadow sharpened on the tarpaper wall.

The sound…curdled!

The light split. Each arm zigged and zagged, separate, ragged-edged and magnesium bright. The right arm split again. The left one was almost directly above us.

And Tak had no shadow at all. I stood up, helped Lanya to…

Some of the light flickered out. More came. And more.

“But what is…?” she whispered right at my ear, pointing. From the horizon, another light ribboned, ragged, across the sky.

“Is it…lightning?” Denny shouted.

“It looks like lightning!” Tak shouted back.

Someone else said: “’Cause George don’t shine that bright!”

Tak’s bleached face twisted as if beat by rain. The air was dry. Then I noticed how cool it was.

Nodes in the discharge were too bright to look at. Clouds—sable, lead, or steel—mounded about the sky, making canyons, cliffs, ravines; for lightning it was too slow, too wide, too big!

Was that thunder? It roared like a jet squadron buzzing the city, and sometimes one would crash or something, and Lanya’s face would

Here one page, possibly two, is missing.

Don’t remember who had the idea, but during the altercation, for a while I argued: “But what about Madame Brown? Besides, I like it here. What are we going to do when you’re at school? Your bed’s okay for a night, but we can’t sleep there that long.”

Lanya, after answering these sanely, said: “Look, try it. Denny wants to come. The nest can get along without you for a few days. Maybe it’ll do your writing some good.” Then she picked up the paper that had fallen behind the Harley, climbed over it, came out from under the loft, tip-toed with her head up and kissed me. And put the paper in her blouse pocket—bending over, it had pulled out all around her jeans.

I pushed myself to the loft edge, swung my legs over, and dropped. “Okay.”

So Denny and I spent what I call three days and she calls one (“You came in the evening, spent the night and the next day, then left the following morning! That’s one full day, with tag ends.” “That should at least count for two,” I said. “It seemed like a long time…”) which wasn’t so bad but…I don’t know.

The first night Madame Brown put supper together out of cans with Denny saying all through: “You wanna let me do something…? Are you sure I can’t do nothin’…? Here, I’ll do…” and finally did wash some pans and dishes.

I asked, “What are you making?” but they didn’t hear so I sat in the chair by the table alternately tapping the chair-back on the wall and the front legs on the floor; and drank two glasses of wine.

Lanya came in and asked why I was so quiet.

I said: “Mulling.”

“On a poem?” Madame Brown asked.

We ate. After dinner we all sat around and drank more, me a little more than the others, but Madame Brown and I actually talked about some things: her work, what went on in a scorpion run (“You make it sound so healthy, I mean like a class trip, I’m not so sure that I like the idea as much now. It sounded very exciting before you told me anything about it.”), the problems of doctors in the city, George. I like her. And she’s smart as hell.

Back in Lanya’s room, I sat at the desk in the bay window, looking at my notebook. Lanya and Denny went to bed (“No, the light won’t bother us”), and after about fifteen minutes, I joined them and we made cramped, languorous love which had this odd, let’s-take-turns thing about it; but it was a trip. I nearly knocked over the big plant pot by the bed four times.

I woke before the window had lightened, got up and prowled the house. In the kitchen, considered getting drunk. Made myself a cup of instant coffee instead, drank half, and prowled some more. Looked back into Lanya’s room: Denny was asleep against the wall. Lanya was on her back, eyes opened. She smiled at me.

I was naked.

“Restless?”

“Yeah.” I came over, squatted by the bed, hugged her.

“Go ahead. Pace some more. I need another couple of hours.” She turned over. I took up the old notebook here, sat around cross-legged on the floor, contemplating writing down what had happened till then.

Or a poem.

Did neither.

Looked in the top desk drawer—the wood looks like paper had been glued all over it and then as much pulled off as possible. She said some friends lugged it from a burned-out windshield warehouse a few blocks down the hill.

I took out the poems she’d saved, spread them on the gritty wood, on every kind of paper, creased this way and that (red-tufted begonia stalks doffed), and tried to read them.

Couldn’t.

Thought seriously of tearing them up.

Didn’t.

But understood much about people who have.

Looked back at Lanya; bare shoulders, the back of her neck, a fist sticking from under the pillow.

Prowled some more.

Got back into bed.

Denny jerked his head up, blinking. He didn’t know where he was. I rubbed the back of his neck and whispered, “It’s okay, boy…” He settled back down, nuzzling into Lanya’s armpit. She turned away from him toward me.

I woke alone.

Leaves arched over me. I looked up through them. Blew once to see if they’d move, but they were too far. Closed my eyes.

“Hey,” Denny said. “You still asleep?”

I opened my eyes. “Fuck you if I was.”

“I just walked Lanya over to school.” He leaned against the edge of the doorway, holding his chains. “It’s nice around here, huh?”

I sat up on the side of the bed.

“But there ain’t too much to do…it’s nice of her to have us over here, I mean to stay a while, huh?”

I nodded.

About two hours later he told me he was going out. I spent the rest of the morning staring at blank paper—or prowling.

Madame Brown, coming out of her office, saw me once and said: “You look strange. Is anything the matter?”

“No.”

“Are you just bored?”

“No,” I said. “I’m not bored at all. I’m thinking a lot.”

“Can you leave off long enough for a lunch break?”

“Sure.” I hadn’t had breakfast.

Tuna fish salad.

Canned pears.

We both had a couple of glasses of wine. She asked me for my character impressions of: Tak, Lanya, Denny, one of her patients I had met at the bar once; I told her and she thought what I said was interesting; told me hers, which I thought were interesting too, and they changed mine; so I told her the changes. Then the next patient came by and I went back to staring at my paper; prowling; staring.

Which is what I was doing when Lanya and Denny came in. He’d gone back to the school to help out with the class.

“Denny suggested we go on a class trip, outside to look at the city. We did. It turned out to be a fine idea. With two of us we didn’t have any problem handling them. That was a good idea, Denny. It really was.” Then she asked if I’d written anything.

“Nope.”

“You look strange,” she told me.

Denny said: “No he don’t. He just gets like that sometimes.”

Lanya Mmmmed. She knows me better than he does, I guess.

Denny was really into being useful—a trait which, pleasant as he is, I’ve never seen in him before. I helped them do a couple of things for Madame Brown: explore the cellar, take one chair down, bring up a dresser she’d found on the street and managed to get to the back door.

It was a nice evening.

I wondered if I was spoiling it by suggesting: “Maybe we should go back to the nest tonight?”

Lanya said: “No. You should use some of this boring peace and quiet to work in.”

“I’m not bored,” I said. And resolved to sit in front of a piece of paper for at least an hour. Which I did: wrote nothing. But my brain bubbled and bobbed and rotated in my skull like a boiling egg.

When I finally went to bed I fell out like an old married man.

One of them or the other got up in the night to take a leak, came back to bed brushing aside the plants and we balled, hard and a little loud I think.

In the morning we all got up together.

I noticed Lanya noticing me being quiet. She noticed my noticing and laughed.

After coffee we all walked to the school. Denny asked to stick around for the class. Now I noticed her wondering if two days in a row was a good idea. But she said, “Sure,” and I left them and went back to the house, stopping once to wonder if I should go back to the nest instead.

Madame Brown and I had lunch again.

“How are you enjoying your visit?”

“Still thinking a lot,” I told her. “But I also think all this thinking is about to knock me out.”

“Your poetry?”

“Haven’t written a word. I guess it’s just hard for me to write around here.”

“Lanya said you weren't writing too much

at your place, either. She said she thought

there were too many people around.”

“I don’t think that’s the reason.”

We talked some more.

Then I came to a decision: “I’m going back to the nest. Tell Lanya and Denny when they get back, will you?”

“All right.” She looked at me dubiously over a soup spoon puddled with Cross & Blackwell vichyssoise. “Don’t you want to wait and tell them yourself when they get back?”

I poured another glass of wine. “No.”

When the next patient rang, I took my notebook and wandered (for five, funny minutes, midway, I thought I was lost) back to the nest.

Tarzan and the apes, all over the steps, were pretty glad to see me. Priest, California, and Cathedral did a great back-slapping routine down the hall. Glass nodded, friendly but overtly non-committal. And I had a clear thought: If I left, Glass, not Copperhead, would become leader.

I climbed up into the loft, told Devastation’s friend Mike to move his ass the hell over.

“Oh, yeah, Kid. Sure, I’m sorry. I’ll get down—”

“You can stay,” I said. “Just move over.” Then I stretched out with my notebook under my shoulder and fell asleep, splat!

Woke up logy but clutching for my pen. Took some blue paper to the back steps, put the pine plank across my knees and wrote and wrote and wrote.

Went back into the kitchen for some water.

Lanya and Denny were there.

“Hi.”

“Oh, hi.”

Went back to the porch and wrote some more. Finally it was

as loud as I could: “Lanya! Denny!” If they answered, I couldn’t hear; and I was hoarse from shouting. The street sign chattered in its holder—the wind had grown that strong.

I took another half dozen steps, my bare foot on the curb, my boot in the gutter. Dust fits hit my face. My shadow staggered around me on the pavement, sharpening, blurring, tripling.

People were coming down the street, while the darkness flared behind them.

That slow, crazy lightning rolled under the sky.

The group milled toward me; some dodged forward.

One front figure supported another, who seemed hurt. I got it in my head it was the commune: John and Mildred leading, and something had happened to John. A brightening among the clouds—

They were thirty feet nearer than I’d thought:

George looking around at the sky, big lips a wet cave around his teeth’s glimmer, his pupils under-ringed with white, and glare flaking on his wet, veined temples, supporting Reverend Taylor; she leaned forward (crying? laughing? cringing from the light? searching the ground?), her hair rough as shale, her knuckles and the backs of her nails darker than the skin between.

The freckled, brick-haired Negress, among darker faces, walked behind them; with the blind-mute; and the blond Mexican.

Someone was shouting, among others shouting: “You hear them planes? You hear all them planes?” (It couldn’t have been planes.) “Them planes are awfully low! They gonna crash! You hear—” at which point the building face across the street cracked, all up and down, and bellied out so slow I wondered how. Cornices, coping stones, window frames, glass and brick hurled across the street.

They screamed—I could hear it over the explosion because some were right around me—and ran against the near wall, taking me with them and I crashed into the people in front of me, wind knocked out of me by the people behind, screaming; someone reached over my shoulder for support, right by my ear, and nearly tore it off. More people (or something?) hit the people behind me, hard.

Coughing and scrambling, I turned to push someone from behind me. Across the street, girders, scabby with brick and plaster, tessellated luminous dust. I staggered from the wall among the staggering crowd and stumbled into a big woman on her hands and knees, shaking her head.

I tried to pull her up, but she got back down on her knees again.

What she was trying to do, I realized, was roll a pile of number ten tomato-juice and pineapple-juice cans and crumpled cookie packages back into her overturned shopping bag. Her black coat spread around her over crumbs of brick.

One can rolled against my foot. It was empty.

She began to go down, even further, laying her cheek on the pavement, reaching among the jangling cans. I bent to pull her once more. Then someone, yanking her from the other side, shouted, “Come on!” (Cŭm ōhn! the vowels, long and short, braying: the m soft as an n; the n loose as an r.) I looked up without letting go.

It was George.

She came up between us, screaming: “Ahhhhhhhhhh—Annnnnn! Don’t touch me! Ahhhhhhhhh—don’t touch me, nigger!” She staggered and reeled in our grip. I didn’t see her look at either of us. “Ahhhhh—I saw what you done!—that poor little white girl what couldn’t do no thin’ against you! We saw it! We all saw it! She come lookin’ for you, askin’ all a-round, askin’ everybody where you are all the time, and now you take her, take her like that, just take her like you done! And see what’s happened! Now, see! Oh, God, oh help me, don’t touch me, oh, God!”

“Aw, come on!” George shouted again as once more she started to collapse. He pulled again; she came loose from my grip. The coat stung my hands. As I dodged away, she was still shrieking:

“Them white people gonna get you, nigger! Them white men gonna kill us all ’cause of what you done today to that poor little white girl! You done smashed up the store windows, broke all the streetlights, climbed up and pulled the hands down from the clock! You been rapin’ and lootin’ and all them things! Oh, God, there’s gonna be shootin’ and burnin’ and blood shed all over! They gonna shoot up everything in Jackson. Oh, God, oh, God, don’t touch me!”

“Will you shut up, woman, and pick up your damn junk,” George said.

Which, when I looked back, seconds later, was what she was doing.

George, ten feet off, squatted to haul up a slab of rubble that rained plaster from both sides, while another woman tugged at a figure struggling beneath. A handful of gravel hit my shoulder from somewhere and I ducked forward.

Ahead of me, turning and turning in the silvered wreckage, Reverend Amy squinted up, fists moving above her ears, till her fingers jerked wide; the up-tilted face was scored with what I thought rage; but it swung again and I saw that the expression struggling with her features was nearer ecstasy.

I climbed over fallen brick. The orchid rolled and bounced on my belly.

The blind-mute was sitting on the curb near the hydrant. The blond Mexican and the brick-haired Negress squatted on either side. She held his hand, pressing her fist, the fingers rearranged and rearranged, at each contact, against his palm.

I reached among my chains, found the projector ball, and fingered the bottom pip.

The disk of blue light slid up the rubbly curb as I stepped to the sidewalk.

They looked up, two with eyes scarlet as blood-bubbles.

The mute’s sockets (he poked his head about) were like empty cups dregged with shadow.

There was a sudden stinging in my throat from the smoke; smoke blew away. I shouted: “What are you doing?”

The Mexican dragged his boots back against the curb. The woman put her other hand on the mute’s shoulder.

I watched their movements of surprise. Translated to their hands on the blind-mute’s arms, it gave him his only knowledge of me. His face tilted forward; his hand closed on the woman’s—my knowledge of what he knew. Thinking: It takes so little information…Though I am cased in light and their eyes orbited with plastic, in the over-determined matrix, translated and translated, perhaps his knowledge of me is even more complete.

I was frightened of their red eyes?

What does my blue beast become behind scarlet caps!

People shouted.

I shouted louder: “What’s going on? What’s happening? Do you know?” and ended coughing in more smoke.

The brick-haired Negress shook her head, a hand before her mouth, hesitant to quiet me, pinch her own lips closed, or push me away. “Somebody put a bomb in…Didn’t they? Isn’t that what they said? Somebody put a—”

“No!” the Mexican said loudly. He tugged the blind-mute’s shoulders. “There wasn’t any—anything like that…” He got the blind-mute on his feet.

I turned to see men and women stumbling toward me, against the luminous mist. And something behind the mist flickered. I lurched into the street.

“There wasn’t any bomb!” the man or the woman behind me shrieked. “They shot him! From up on the roof. Some crazy white boy! Shot him dead in the street! Oh, my God—”

Something warm splattered my ankle.

Water rolled between the humped cobbles, bright as mercury beneath the discharges on the collapsed, black sky. The street was a net of silver and I sprinted across it, catching one woman with my shoulder who spun—shouting—her scraped face after me, almost lunged into another man, but pushed off him with both hands; a sudden gust of heat stung through the roofs of my eye-sockets. Lids clamped, I got through it and more dust, catching my boot-toe on something that nearly tripped me. I coughed and staggered with the back of my hand over my mouth.

Something went over the back of my neck, so cold I thought it was water. But it was just air. Eyes tearing, my throat spasming and hacking free of the dust caught in it, I staggered through it a dozen steps, till somebody grabbed me and I came up, staring at another black face.

“It’s Kid!” Dragon Lady shouted to somebody and got her arm around me to keep me from falling.

A few steps behind her Glass turned around to see me. “Huh?”

Beyond him, against a screen of slowly moiling clouds, the side came off a twenty-story building, collapsing slowly away from the web of steel. But that must have been five blocks down.

“Jesus Christ…!” D-t said, then glanced back at me. “Kid, you all—?” and the sound got to us, filling up the space around us the way a volcano must up close.

The brunt of it past, I could hear people behind me still shouting: Three different voices bawled out instructions among some fifty more who didn’t care.

“Goddamn it!” D-t said. “Come on!”

Someone had strewn coils of what looked like elevator cable all over the sidewalk. It was greasy too; so after the first dozen steps across it, we went into the street.

And the shouting behind us had resolved to a single, distant, insistent voice—“You wait, Goddamn it! You hear me, you motherfuckers wait for me!”—getting closer—“Wait for me, Goddamn it! Wait—!”

I looked back.

Fireball, fists pumping, bent forward from the waist and head flung back, ran full into Glass, who caught him by the arm. Fireball sagged back, gasping and crying: “You wait for me, Goddamn it! You damn niggers—” he sucked in a breath loud as vomiting—“why didn’t you wait!” He was barefoot, with no shirt; a half dozen chains swung and tinkled from his neck as he bent, gasping, holding his stomach. In a pulse of light I saw he had a scrape down his jaw that went on across his shoulder blade as though something had fallen on him while he ran. His face was streaked with tears that he scrubbed with the flat of his fist. “You God damn fuckin’ niggers, you wait for me!”

“Come on,” D-t said. “You all right now.”

I thought Fireball was going to fall down trying to get back his breath.

Somebody else sprinted up the street, out of the smoke. It was Spider. He looked very young, very tall, very black, and very scared. Breathing hard, he asked: “Fireball okay? I thought a damn wall fell on him.”

“He’s okay,” D-t said. “Now let’s go!”

Fireball nodded and lurched ahead.

Glass let him go and moved beside me. His vinyl vest was hazed across with powdered plaster. “Hey,” I said, “I’ve gotta find Lanya and Denny. They’re supposed to be going back to the nest—”

“Oh, God damn, nigger!” Fireball twisted back to stare. His face was smeared filthy, and some of it was blood. “Leave them white motherfuckers alone, huh? Don’t you think about nothin’ except your pecker?”

“Now you just get yourself together!” Dragon Lady pushed Fireball’s shoulder sharply with the heel of her hand; when he jerked around, she took his arm like they were going for a stroll. “Let’s you just cut this ‘nigger’ shit, huh? What you think you are, a red-headed Indian?”

Glass said: “We don’t got any nest; not anymore.”

“They got any sense,” D-t said, “they gonna be trying to get out too. Maybe we meet up with them at the bridge.”

“What happened to the others?” I asked. “Raven, Tarzan, Cathedral? Lady of Spain…What about Baby and Adam?”

Dragon Lady didn’t even look back.

“You were the last one out,” D-t said to Spider. “You see ’em?”

Spider looked from D-t to me and back. “No.” He looked down where he was holding onto the end of his belt with his lanky, black fingers, twisting a little.