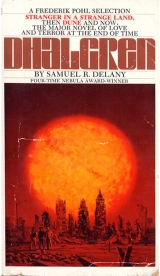

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 59 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“Maybe,” Dragon Lady said, letting go Fireball’s arm but still not looking back, “we gonna meet ’.” I could tell she was frowning. “On the bridge. Like he says.” Or something else.

I walked another five steps, looking down at the wet pavement, feeling numbness claw at me. My fingers tingled. So did the soles of both feet. Then I looked up and said, “Well, Goddamn it, the bridge is that way!” Which is when this incredibly loud crackling started on our left.

We all looked up, turned our heads, backed away all together. Spider broke, ran a dozen steps, realized we weren’t coming, and turned back to look too.

Four stories up, fire suddenly jetted from one window. The flames flapped up like yellow cloth under a bellows; sparks and glass tumbled down the brick.

Two more windows erupted. (I hit my bare heel on the far curb.) Then another—as far apart as ticks on a clock.

We ran.

Not down the way I said because that street was a-broil with smoke and flickering. At the end of another block, we turned the corner and ran down the sloping sidewalk. There was water all over one end.

D-t and me splashed into it, watching the high brick walls, and the billowing clouds between them, shatter below our feet.

Ten yards in it was up to my knees and I couldn’t really run. We slushed on. Glass, arms swinging wide in a wildly swaying stagger, moved ahead of me, dragging fans of ripples from the backs of his soaked pants. Then the street started sloping up. I splashed toward the edge.

What it felt like was something immense dropped into the street a block away. Everything shook. I looked back at the others—Fireball and Dragon Lady were still splashing forward—when, in the center, was a swell of what looked like detergent bubbles. Then steam shot straight up. The water’s edge rolled back from Fireball’s dripping cuffs, leaving his wet feet slapping the glistening pavement.

Glass back-tracked to grab Dragon Lady’s hand, like he thought she (or he) might fall.

The geyser spit and hissed and the water bubbled into it.

We went around the next corner together.

I could see the bridge all the way to the second stanchion. Here and there clouds had torn away from the black sky. Something was burning down between the waterfront buildings. We rushed across fifty feet of pavement. Just before the bridge mouth, it looked like someone had grenaded the road. A slab of asphalt practically fifteen feet high jutted up. Down the crack around it, you could see wet pipes, and below that, flickering water. Above, that amazing, loud lightning formed its searing nodes among the cloud canyons.

“Come on,” I said. “This way!”

Metal steps lead up to the bridge’s pedestrian walk. The first half dozen were covered with broken masonry. Glass and Dragon Lady charged right up. Plaster dust puffed out between the railing struts. Fireball stepped carefully on the first three steps, then grabbed both railings and vaulted up three more. His feet were caked with junk and he was bleeding from one ankle.

“Get goin’!” D-t crowded behind. “Get goin’!”

Spider and me went up the narrow steps practically side by side.

At the top, Spider got ahead and we ran along the clanging plates maybe fifty yards when something…hit the bridge!

We swayed back and forth a dozen feet! Metal ground against old metal. Cables danced in the dark.

I grabbed the rail, staring down at the blacktop fifteen feet below, expecting it to split over the water a hundred feet below that.

Beside me, Fireball just dropped on his knees, his cheek against the bars. Spider put his arms around the dead lamppost, bent his head and went, “Ahhhhhhhhh…” like he was crying with his mouth open—which, five seconds later, when the shaking and the creaking died, was the only sound. Dragon Lady swallowed, let go the rail, and took a gasping breath.

My ears were ringing.

Everything was quiet.

“Jesus God,” D-t whispered, “let’s get off o’—” which was when everybody, including D-t, realized how quiet.

Holding the rail tight, I turned to look back.

On the waterfront, flames flickered in smoke. A breeze came to brush my forehead. Here and there smoke was moving off the wind-runneled water. And there was nobody else on the bridge.

“Let’s go…” I stepped around Fireball, passed by Dragon Lady.

A few seconds later, I heard Glass repeat: “Well, let’s go!” Their footsteps started.

Dragon Lady caught up. “Jesus…” she said softly beside me. But that was all.

We kept walking.

Girders wheeled on either side. About twenty feet beyond the first stanchion, I looked back again:

The burning city squatted on weak, inverted images of its fires.

Finally D-t touched my shoulder and made a little gesture with his head. So I came on.

The double, thigh-thick suspensors swung even lower than our walkway; a few yards later they sloped up toward the top of the next stanchion.

“Who is…?” Glass asked softly.

Down on the black-top, she was walking slowly toward us.

Running my hand along the rail, I watched. Then I called: “Hey, you!”

Behind me there was a flare; then another; then another. The others had flicked on their lights—which meant I was in silhouette before a clutch of dragons, hawks, and mantises.

She squinted up at us: a dark Oriental, with hair down in front of her shirt (like two black, inverted flames); red bandanas were stuffed under the shoulder straps of her knapsack for padding. Her shirttails were out of her jeans. “Huh…?” She was trying to smile.

“You going into Bellona?”

“That’s right.” She squinted harder to see me. “You leaving?”

“Yeah,” I said. “You know, it’s dangerous in there!”

She nodded. “I’d heard they had the national guard and soldiers and stuff posted. Hitch-hiking down, though, I didn’t see anybody.”

“How were the rides?”

“All I saw was a pickup and a Willy’s station wagon. The pickup gave me a lift.”

“What about traffic going out?

She shrugged. “I guess if somebody passes you, they’ll give you a ride. Sometimes the truckers will stop for a guy to spell them on driving. I mean, guys shouldn’t have too tough a time. Where’re you heading?”

Over my shoulder, Glass said: “I want to get to Toronto. Two of us are heading for Alabama, though.”

“I just wanted to get someplace!” Fireball said. “I don’t feel right, you know? I ain’t really felt right for two days…!”

“You got a long way to go, either direction,” she said.

I wondered what she made of the luminous light shapes that flanked me and threw pastel shadows behind her on the gridded black-top.

Glass asked: “Everything is still all right in Canada—?”

“—and Alabama?” asked Spider.

“Sure. Everything’s all right in the rest of the country. Is anything still happening here?”

When nobody answered, she said:

“It’s just the closer you get, the funnier…everybody acts. What’s it like inside?”

D-t said: “Pretty rough.”

The others laughed.

She laughed.

“But like you say,” Dragon Lady said, “guys have a pretty easy time,” which I don’t think she got, because unless you listen hard, Dragon Lady’s voice sounds like a man’s.

“Is there anything you can tell me? I mean that might be helpful? Since I’m going in?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Sometimes men’ll come around and tear up the place you live in. Sometimes people shoot at you from the roof—that is, if the roof itself doesn’t decide to fall on you. Or you’re not the person on top of it, doing the shooting—”

“He wrote these poems,” Fireball said at my other shoulder. “He wrote these poems and they published them in a book and everything! They got it all over the city. But then he wrote some more, only they came and burned them all up—” His voice shook on the fevered lip of hysteria.

“You want a weapon,” I asked, “to take in with you?”

“Wow!” she said. “Is it like that?”

Glass gave a short, sharp laugh.

“Yeah,” I said. “We have it easy.”

Spider said: “You gonna tell her about…the Father? You gonna tell her about June?”

“She’ll learn about those.”

Glass laughed again.

D-t said: “What can you say?”

She ran her thumbs down her knapsack straps and settled her weight on one hip. She wore heavy hiking shoes, one a lot muddier than the other. “Do I need a weapon?”

“You gonna give her that?” Dragon Lady asked as I took my orchid off its chain.

“We got ourselves in enough trouble with this,” I said. “I don’t want it with me anymore.”

“Okay,” Dragon Lady said. “It’s yours.”

“Where you from?” Glass was asking.

“Down from Canada.”

“You don’t look Canadian.”

“I’m not. I was just visiting.”

“You know Albright?”

“No. You know Pern?”

“No. You know any of the little towns around Southern Ontario?”

“No. I spent all my time around Vancouver and B.C.”

“Oh,” Glass said.

“Here’s your weapon.” I tossed the orchid. It clattered on the blacktop, rolled jerkily, and stopped.

“What is—?” The sound of a car motor made us all look toward the end of the bridge; but it died away on some turnoff. She looked back. “What is it?”

“How they call that?” Fireball asked.

“An orchid,” I said.

“Yeah,” Fireball said. “That’s what it is.”

She stooped, centered in her multiple shadows. She kept one thumb under her pack-strap; with her other hand she picked it up.

“Put it on,” I said.

“Are you right or left handed?” Glass asked.

“Left.” She stood, examining the flower. “At least, I write with my left.”

“Oh,” Glass said again.

“This is a pretty vicious looking thing.” She fitted it around her wrist; something glittered there. “Just the thing for the New York subway during rush hour.” She bent her neck to see how it snapped. As her hair swung forward, under her collar was another, bright flash. “Ugly thing. I hope I don’t need you.”

I said: “Hope you don’t either.”

She looked up.

Spider and D-t had turned off their lights and were looking, anxiously, beyond the second stanchion toward the dark hills of the safer shore.

“I guess,” I told her, “you can give it to somebody else when you’re ready to be among the dried and crisp branches, trying to remember it, get it down, thinking: I didn’t leave them like that! I didn’t. It’s not real. It can’t be. If it is then I am crazy. I am too tired—wandering among all these, and these streets where the burning, burning, leaves the shattered and the toppling. Brick, no bridge because it takes so long, leaving, I haven’t leaving. That I was following down the dark blood blots her glittering heel left on the blacktop. They slid into the V of my two shadows on the moon and George lit along the I walk on and kept. Leaving it. Twigs, leaves, bark bits along the shoulder, the hissing hills and the smoke, the long country cut with summer and no where to begin. In the direction, then, Broadway and train tracks, limping in the in the all the dark blots till the rocks, running with rusty water, following beside the broken mud gleaming on the ditch edge, with the trees so over so I went into them and thought I could wait here until she came, all naked up or might knowing what I couldn’t, remember maybe if just one of them. He. In or on, I’m not quite where I go or what to go now but I’ll climb up on the and wonder about Mexico if she, come, waiting.

This hand full of crumpled leaves.

It would be better than here. Just in the like that, if you can’t remember anymore if. I want to know but I can’t see are you up there. I don’t have a lot of strength now. The sky is stripped. I am too weak to write much. But I still hear them walking in the trees; not speaking. Waiting here, away from the terrifying weaponry, out of the halls of vapor and light, beyond holland and into the hills, I have come to

—San Francisco, Abaqii, Toronto,

Clarion, Milford, New Orleans,

Seattle, Vancouver, Middletown,

East Lansing, New York, London

January 1969/September 1973

A Biography of Samuel R. Delany

Samuel R. Delany was born April 1, 1942, in New York City. His many works range from autobiography and essays to literary and cultural criticism—some dozen volumes’ worth—to fiction and science fiction, this last his most widely recognized genre. After eleven years as a professor of comparative literature at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, for fourteen years Delany has been a professor of English and creative writing at Temple University in Philadelphia.

With a younger sister, Delany grew up in Harlem—at the time, the city’s black ghetto. His father, Samuel Sr., owned and operated the Levy & Delany Funeral Home. Delany’s mother, Margaret Delany, was a clerk in the New York Public Library system. The family lived in the two floors over Samuel Sr.’s Seventh Avenue business.

Delany’s grandfather, Henry Beard Delany, was born a slave in Georgia in 1857, and became the first black suffrage Episcopal bishop of the Archdiocese of North and South Carolina as well as vice-chancellor of a black Episcopal college, St. Augustine’s, in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Through kindergarten, Delany attended the Horace Mann–Lincoln School and, at age five, began at the Dalton School in New York. When he was eleven, on his first day at a new summer camp, young Samuel renamed himself Chip. It stuck—and his friends still call him that.

For the ninth grade, he went on to the Bronx High School of Science. On his first day, Delany met and became friends with the young poet Marilyn Hacker. A year younger than Delany but a year ahead of him in school, Hacker was accepted at New York University at age fifteen. Three years later, Delany, now nineteen, and Hacker, eighteen, were married in Detroit and, on returning to New York, took up residence in a tenement on a dead-end street in the recently renamed East Village.

Delany finished and sold his first published novel, The Jewels of Aptor, when he was still nineteen. It appeared in November 1962, seven months after his twentieth birthday. Before his twenty-second, he’d completed and sold four more novels, including a trilogy that was originally released one at a time, but today is usually published in one large volume: The Fall of the Towers.

Though the reviews were all good, there were not many. No one paid much attention to the new young writer until the shortest of those four books, The Ballad of Beta-2, was nominated for the first Nebula Award in the novella category—given by the then-new organization the Science Fiction Writers of America. The book did not win, and Delany was unaware the book had been nominated till years later. However, that he made any showing at all, considering his age and his unknown status, is remarkable.

On April 15, 1966, Delany returned to New York from six months in Europe, a trip that was to influence all his work over the coming years. In the meantime, another short novel, Empire Star, had appeared, followed by Babel-17.

In March of ’67, this last title won the year’s Nebula, in a tie with Daniel Keyes’s Flowers for Algernon. A year later, Delany won two more Nebulas, the first for his novel The Einstein Intersection, and the second for his short story “Aye, and Gomorrah.” This period climaxed two years later with the publication of his novel Nova, finished a month after his twenty-fifth birthday, and the publication of his short story collection Driftglass. Today Nova remains among Delany’s most popular books. Now, however, came five years with no novels.

Delany had identified as gay since his tenth year, and his marriage with Hacker was an open one for both of them. In this time they lived together and apart, now in San Francisco for two years, now in New York, now in London, where, in 1974, their daughter was born.

That same year Dhalgren, Delany’s most controversial work, made its appearance. At eight hundred seventy-nine pages in its initial Bantam Books edition, it drew much praise, much scorn—and open anger. Over the next dozen years, however, it sold more than a million copies and, today, has settled comfortably into the slot reserved for “classics of the genre.” As Delany’s most popular book, it has been turned into both a play on the East Coast and an opera on the West.

A year after Dhalgren, Delany’s highly acclaimed Trouble on Triton was published. From 1979 to 1987, Delany wrote a connected set of eleven fantasy tales: two novels, three novellas, and six short stories. They include The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals (1987)—the first novel about AIDS released by a major American publisher—and the Return to Nevèrÿon series. In 1984 Delany’s last purely SF novel for twenty-five years would appear, Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand—a book in which he predicted the Internet a decade before the fact.

Since then, Delany has written highly praised works, both fictitious and autobiographical. His 1988 publication, The Motion of Light in Water, is a staple of gender studies and African American studies classes and received a Hugo Award for nonfiction. In 1995, he published three long stories, about black life in the Jazz Age, the fifties in New York, and the sixties in Europe, collected in Atlantis: Three Tales and, partly, in The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. This was followed by collections of interviews and nonfiction essays, including Silent Interviews (1994), Longer Views (1996), and Shorter Views (1999), all published by Wesleyan University Press.

Among his highly acclaimed academic releases are Times Square Red, Times Square Blue—the first part of which began as the Distinguished Faculty Lecture at the University of Massachusetts in March 1998, and the second of which is an expansion of an article written for Out magazine—and About Writing. Other novels, long and short, from this time include The Mad Man, Hogg (“the most shocking novel of the 20th century,” wrote Larry McCaffery), and Phallos. His novel about a black gay poet living in the East Village over the turn of the most recent century, Dark Reflections, won the 2008 Stonewall Book Award. His most recent novel, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders (2012), is over eight hundred pages—an amalgam of gay erotic writing, rural realism, and science fiction. Discussions over it seem to be progressing in a manner similar to that of the controversy almost forty years ago over Dhalgren.

Altogether, Delany has won four Nebula Awards and two Hugo Awards, as well as the Bill Whitehead Award for a lifetime contribution to gay and lesbian writing. In 2002, Delany was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. He received the Pilgrim Award for SF scholarship in 1985 and the J. Lloyd Eaton Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010. That same year he was among the judges for the National Book Award in Fiction. In 2007 he was the subject of Fred Barney Taylor’s documentary The Polymath, or, The Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman, which includes an experimental color film, The Orchid, which Delany himself wrote, directed, and edited in 1972.

Delany, age twenty-four, at the 1966 World Science Fiction Convention. At right are science fiction editor Terry Carr and his wife, Carol. Photo courtesy of Andrew Porter.

The Ace Books first printing of Babel-17, which won the 1966 Nebula Award for Best Novel.

Delany in 1966 with author and editor Lin Carter. Photo courtesy of Andrew Porter.

Delany at the 1980 World Science Fiction Convention in Boston. Photo courtesy of Andrew Porter.

Delany giving a lecture at the New York Public Library in 1991. Photo courtesy of Andrew Porter.

The cover of the 2007 documentary The Polymath, or, The Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman. More information on this film may be found at maestromedia.net.

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

“The Tale of Rumor and Desire” first appeared in Callaloo, a Tri-Annual Journal of Black South Arts and Letters, Spring-Summer 1987, Johns Hopkins University Press. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agent, Henry Morrison, Inc.

“The Tale of Gorgik” first appeared, in a somewhat shorter form, in Asimov’s SF Adventure Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 3, Summer 1979, and is reprinted by permission of the author and his agent, Henry Morrisson, Inc.

Originally published as The Bridge of Lost Desire

Copyright © 1987, 1989, 1994 by Samuel R. Delany

Cover design by Michel Vrana

978-1-4804-6168-0

This edition published in 2014 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.openroadmedia.com