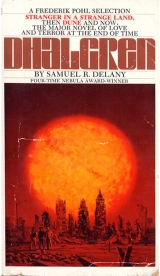

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

In its long-stemmed dessert dish, the yellow hemisphere just cleared the syrup.

Kidd looked at it, his face slack, realized his lips were hanging a little open, so closed them.

Beneath the table, he clutched the table-leg so tight a band of pain finally snapped along his forearm. He let go, let out his breath, and said: “Thank you…”

“It’s not terribly exciting,” Mrs. Richards said. “But fruit has lots of vitamins and things. I made some whipped cream—dessert topping, actually. I do like real cream, but this was all we could get. I wanted to flavor it almond. I thought that would be nice. With peaches. But I was out of almond extract. Or vanilla. So I used maple. Arthur, would you like some? Edna?”

“Lord, no!” Madame Brown waved the proffered bowl away. “I’m heavy enough as it is.”

“Kidd, will you?”

The bowl came toward him between the candles, facets glittering. He blinked, worked his jaw slowly inside the mask of skin, intent on constructing a smile.

He spooned up a white mound—with the flame behind it, its edges were pale green.

Madame Brown was watching him; he blinked. Her expression shifted. To a smile? He wondered what his own was. It was supposed to be a smile too; it didn’t feel like one…

He buried his peach.

White spiraled into the syrup.

“You know what I think would be lovely?” Mrs. Richards said. “If Kidd read us one of his poems.”

He put half his peach in his mouth and said, “No,” swallowed it, and added, “thanks. I don’t really feel like it.” He was tired.

June said, “Kidd, you’re eating with the whipped cream spoon.”

He said: “Oh…”

Mrs. Richards said, “Oh, that’s all right. Everybody’s had some who wants some.”

“I haven’t,” Mr. Richards said.

Kidd looked at his dish (a half a peach, splayed open in syrup and cream), looked at his spoon (the damasking went up the spoon itself, streaked with cream), at the bowl (above the faceted edges, gouges had been cut into the heaped white).

“No, that’s all right,” Mr. Richards said. Glittering, the bowl moved off beyond the candle flames. “I’ll just use my spoon here. Everybody makes mistakes. Bobby does that all the time.”

Kidd went back to his peach. He’d gotten whipped cream on his knuckles. And two fingers were sticky with syrup. His skin was still wrinkled from the bath. The gnawed and sucked callous looked like he imagined leprosy might.

Arthur Richards said something.

Madame Brown answered something back.

Bobby ran through the room; Mrs. Richards yelled at him.

Arthur Richards said something else.

Cream, spreading through the puddle in the bottom of his dish, finally met glass all the way around. “I think I’m going to have to go soon.” He looked up.

The gold knot of Mr. Richard’s tie was three inches lower on his shirt.

Had he loosened it when Kidd was not looking? Or did he just not remember? “I have to meet somebody before it gets too late. And then…” He shrugged: “I want to get back here to work early tomorrow morning.”

“Is it that late?” Mrs. Richards looked disappointed. “Well, I guess you need a good night’s sleep after all that furniture-moving.”

Madame Brown put her linen napkin on the table. (Kidd realized he had never put his in his lap; it lay neatly, by the side of his stained and spotted place, a single drop of purple near the monogrammed R.) “I’m feeling a little tired myself. Kidd, if you could wait a minute, I wish you’d walk with me and Muriel. Is there coffee, Mary?”

“Oh, dear…I didn’t put any up.”

“Then we might as well go now. Kidd is anxious. And I certainly don’t want to be out on the streets any later than I have to.”

Downstairs, somebody laughed; the laughter of others joined it, till suddenly there was a series of thumps, like large furniture toppling, bureau, after bedstead, after chiffonier.

Kidd got up from the table—held the cloth in place this time. His arm still hurt. “Mr. Richards, were you going to pay me now, or when I finished the whole job?” Getting that out, he was suddenly exhausted.

Mr. Richards leaned back in his chair. His fists were in his suit coat pockets; the front chair legs lifted. “I imagine you could use a little right now.” One hand came out and up. A bill was folded in it; he’d been anticipating the request. “Here you go.”

“I worked about three and a half hours, I guess. Maybe four. But you can call it three if you want, since I was just getting started.” He took the dark rectangle; it was a single five-dollar bill, folded in four.

Kidd looked at Mr. Richards questioningly, then at Madame Brown, who was leaning over her chair, snapping her fingers for Muriel.

Mr. Richards, both hands back in his pockets, smiled and rocked.

Kidd felt there was something else to say, but it was too difficult to think of what. “Um…thank you.” He put the money in his pants pocket, looked around the table for June; but she had left the room. “Good night, Mrs. Richards.” He wandered across green carpet to the door.

Behind him, as he clicked over lock after lock—there were so many—Madame Brown was saying: “Good night, Arthur. Mary, thanks for the dinner. June…? June…?” she called now—“I’m on my way, dear. See you soon. Good night, Bobby—Oh, he’s back in his room. With that book I bet, if I know Bobby. Muriel, come along, sweetheart. Right with you, Kidd. Good night again.”

The smoke was so thick he wondered if the glass were opaque and he only misremembered it as clear—

“Well—” Madame Brown pushed open the cracked door—”what do you think of the Richards after your first day on the job?”

“I don’t think anything.” Kidd stretched in the over-thick night. “I’m just an observer.”

“I take that to mean you’ve thought a great deal but find it difficult, or unnecessary, to articulate.” Muriel clicked away down the cement walk. “They are perplexing.”

“I wish,” Kidd said, “he’d paid me for the whole day. Of course, if they’re feeding me and stuff—” another highrise loomed before them, tier on tier of dark windows—“five dollars an hour is a lot.” Smoke crawled across the facade. He had thought about them, of course; he remembered all his mulling while he worked in the upstairs apartment. And—again she was right—he’d certainly reached no synopsizable conclusion.

Madame Brown, hands behind her back, looked at the pavement, walked slowly.

Kidd, notebook before him in both hands (He’d almost forgotten it; Madame Brown had brought it to him at the door), looked up and could make out practically nothing. “You’re still working in that hospital?”

“Pardon me?”

“That mental hospital, you were talking about.” Walking revived him some. “With the children. Do you still go there every day?”

“No.”

“Oh.”

When she said nothing more, he said:

“I was in a mental hospital. For a year. I was just wondering what happened with—” he looked around at building faces whose wreckage was hidden behind night and smoke; he could smell smoke here—“with yours.”

“You probably don’t want to know,” she said, walking a few more steps in silence. “Especially if you were in one. It wasn’t pleasant.” Muriel spiraled back and away. “You see, I was with the hospital’s Social Service Department—you must have gathered that. Lord, I got twenty-two phone calls at home in two hours about evacuation procedures—the phone went dead in the middle of the last one. Finally, we just decided, even though it was the middle of the night, we’d better go to the hospital ourselves—my friend and I; you see, I had a little friend staying with me at the time. When we got there—walking, mind you—it was just incredible! You don’t expect doctors around at midnight in a place as understaffed as that. But there was not one orderly, one night nurse, one guard around! They’d just gone, like that!” She flung up her hand, in stark dismissal. “Patients were all up in the open night wards. We let out everybody we could. Thank God my friend found the keys to that incredible basement wing they first shut down fifteen years ago, and have been opening up and shutting down regularly—with not a bit of repair!—every three years since. You could see the fires out the windows. Some of the patients wouldn’t leave. Some of them couldn’t—dozens were logy in their beds with medication. Others were shrieking in the halls. And if all those phone calls about evacuation did anything besides scare off whatever staff was around, I’m sure I didn’t see it! Some rooms we just couldn’t find keys to! I broke windows with chairs. My friend got a crowbar, and three of the patients helped us break in some of the doors—Oh, yes: Did I mention somebody tried to strangle me? He just came up in his pajamas, while I was hurrying down the second floor corridor, grabbed me, and started choking. Oh, not very seriously, and only for about two or three minutes, before some other patients helped me get him off—apparently, as I discovered, it takes quite a bit of effort to really choke somebody to death who doesn’t want to be choked. And, believe me, I didn’t. But it was a doozer. I was recovering from that in the S.S. office, when she came in with these.” He heard Madame Brown finger the chains around her neck: it was too dark to see glitter. “My friend. She said she’d found them, wound them around my neck. You could see them flashing in flickers coming from outside, around the window shades.” Madame Brown paused. “But I told you about that…?” She sighed. “I also told you that was when she left…my friend. Some of the rooms, you see, we just couldn’t get into. We tried—me, the other patients, we tried! And the patients on the inside, trying just as hard! Christ, we tried! But by then, fire had broken out in the building itself. The smoke was so thick you could hardly—” She took a sudden breath. Did she shrug? “We had to leave. And, as I said, by that time, my little friend had left already.”

He could see Madame Brown beside him now.

She walked, contemplating either the past or the pavement.

Muriel wove ahead, barked, turned, ran.

“I went back once,” she said at last. “The next morning. I don’t want to go again. I want to do something else…I’m a trained psychologist. Social service was never really my forte. I don’t know if the patients who got out were finally evacuated or not. I assume they were; but I can’t be sure.” She gave a little humph. “Perhaps that has something to do with why I don’t leave myself.”

“I don’t think so,” Kidd said, after a moment. “It sounds like you—and your friend—were very brave.”

Madame Brown humphed again.

“It’s just—” he felt uncomfortable, but it was a different discomfort than at the table—“you made it sound, when you were talking about it at dinner, like you still worked there. That’s why I asked.”

“Oh, I was just making conversation. To keep Mary entertained. When people take the trouble to bring out the best in her, she’s quite a handsome woman; with quite a handsome soul—even if the quotidian surface sits on it a bit askew. I imagine some people find that hard to see.”

“Yeah.” He nodded. “I guess so.” Half a block ahead, Muriel was a shifting dollop of darkness. “I thought—” on the curb, he scraped his heel—“Hey, watch…!” He staggered. “Um. I thought you said they had three children.”

“They do.”

They crossed the damp street. On cool pavement, his heel stung.

“Edward, the oldest, isn’t with them now. But it isn’t a subject I’d bring up. Especially with Mary. It was very painful for her.”

“Oh.” He nodded again.

They stepped up another curb.

“If nothing’s functioning around here,” Kidd asked, “why does Mr. Richards go in to work every day?”

“Oh, just to make a showing. Probably for Mary. You’ve seen how keen she is on appearances.”

“She wants him to stay home,” Kidd said. “She’s scared to death!—I was pretty scared too.”

Madame Brown considered a few moments. “Maybe he does it just to get away.” She shrugged—it was light enough to see it now. “Perhaps he just goes off and sits on a bench somewhere.”

“You mean…he’s scared?”

Madame Brown laughed. “Why wouldn’t he be?” Muriel ran up, ran off. “But I think it’s much more likely he simply doesn’t appreciate her. That isn’t fair of me, I know; but then, it’s one of those universal truths about husbands and wives you really don’t have to be fair with. He loves her, in his way.” Muriel ran up again, leapt to Madame Brown’s hip. She roughed the beast’s head. Satisfied, it ran off again. “No, he must be going somewhere! Probably just where he says he is. To the office…the warehouse…” She laughed. “And we’ve simply got far too poetic an imagination!”

“I wasn’t imagining anything.” But he smiled. “I just asked.” In the light from a flickering window, a story above them, he saw, through faint smoke, she was smiling too.

Ahead, Muriel barked.

And what have I invested in interpreting disfocus for chaos? This threat: the only lesson is to wait. I crouch in the smoggy terminus. The streets lose edges, the rims of thought flake. What have I set myself to fix in this dirty notebook that is not mine? Does the revelation that, though it cannot be done with words, it might be accomplished in some lingual gap, give me the right, in injury, walking with a woman and her dog, to pain? Rather the long doubts: that this labor tears up the mind’s moorings; that, though life may be important in the scheme, awareness is an imperfect tool with which to face it. To reflect is to fight away the sheets of silver, the carbonated distractions, the feeling that, somehow, a thumb is pressed on the right eye. This exhaustion melts what binds, releases what flows.

Madame Brown opened the bar door for him.

Kidd passed by vinyl Teddy, the bill in his fist. But while he contemplated offering her a drink, someone came screaming across the bar; Madame Brown screamed back; they staggered away. He sat down at the counter’s end. The people whose backs he had seen along the stools, as he leaned forward, gained faces. But no Tak; nor any Lanya. He was looking at the empty cage when the bartender, rolled sleeves tying off the necks of tattooed leopards, said, “You’re a beer drinker, ain’t you?”

“Yeah.” He nodded, surprised.

The bottle clacked the scarred counter board. “Come on, come on! Put it away, kid.”

“Oh.” Wonderingly, he returned the money to his pocket. “Thanks.”

Under a haystack mustache, the bartender sucked his teeth. “What do you think this place is, anyway?” He shook his head, and walked off.

His hand had wandered to his shirt pocket to click the pen. He frowned down, paused above some internal turning: he opened the notebook, held his pen in the air, plunged.

Had he ever done this before? he wondered. With pen to paper and the actual process occurring, it was as though he had never done anything else. But pause, even moments, and it was as if not only had he never done it, but there was no way to be sure that he ever would again.

His mind dove for a vision of perfected anger while his hand crabbed and crossed and rearranged the vision’s spillage. Her eyes struck a dozen words: he chose one in the most relevant tension to the one before. Her despair struck a dozen more; he grubbed among them, teeth clamped against what cleared. And cleared. So gazed at the cage again till the fearful distractions fell, then turned to her. An obtuse time later, he raised his hand, swallowed, and withdrew.

He jabbed the pen back in his pocket. His hand dropped, dead and ugly on the paper. His tongue worked in the back of his mouth while he waited for energy with which to copy. Sounds resolved from the noise. He blinked, and saw the pyramided bottles against the velvet backing. Between his fingers he watched the curling inkline peeled off from meaning. He reached for the beer, drank a long time, put down the bottle, and let his hand drop on the paper again. But his hand was wet…

He took a breath, turned to look left.

“Eh…hello, there,” from his right.

He turned right.

“I thought it might be you when I was on the other side of the bar.” Blue serge; narrow lapels; hair the color of white pepper. “I really am glad to see you again, to know you’re all right. I can’t tell you how upset that whole experience left me. Though that must be a bit presumptuous: You were the one who was hurt. It’s been a long time since I’ve had to move through such suspicion, such restraint.” The face was that of a thin, aged child, momentarily sedate. “I’d like to buy. you a drink, but I was told that they don’t sell the drink here. Bartender?”

Walking his fists on the wood, the bartender came, like some blond gorilla.

“Can you put together a tequila sunrise?”

“Make my life easy and have a beer.”

“Gin and tonic?”

The bartender nodded deeply.

“And another for my friend here.”

The gorilla responded, forefinger to forehead.

“Hey, I’m sort of surprised,” Kidd volunteered into the feeling of loss between them, “to see you in here, Mr. Newboy.”

“Are you?” Newboy sighed. “I’m out on my own, tonight. I’ve a whole list of places people have told me I must see while I’m in town. It’s a bit strange. I gather you know who I…?”

“From the Times.”

“Yes.” Newboy nodded. “I’ve never been on the front page of a newspaper before. I’ve had just enough of that till now to be rather protective of my anonymity. Well, Mr. Calkins thought he was doing something nice; his motives were the best.”

“Bellona’s a very hard place to get lost in.” What Kidd took for slight nervousness, he reacted to with warmth. “I’m glad I read you were here.”

Newboy raised his peppered brows.

“I’ve read some of your poem now, see?”

“And you wouldn’t have if you hadn’t read about me?”

“I didn’t buy the book. A lady had it.”

“Which book?”

“Pilgrimage.”

Now Newboy lowered them. “You haven’t read it carefully, several times, all the way through?”

He shook his head, felt his lips shake, so closed his mouth.

“Good.” Newboy smiled. “Then you don’t know me any better than I know you. For a moment I thought you had an advantage.”

“I only browsed in it.” He added: “In the bathroom.”

Newboy laughed out loud, and drank. “Tell me about yourself. Are you a student? Or do you write?”

“Yes. I mean I write. I’m…a poet. Too.” That was an interesting thing to say, he decided. It felt quite good. He wondered what Newboy’s reaction would be.

“Very good.” Whatever Newboy’s reaction, surprise was not part of it. “Do you find Bellona stimulating, making you produce lots of work?”

He nodded. “But I’ve never published anything.”

“Did I ask if you had?”

Kidd looked for severity; what he saw was a gentle smile.

“Or are you interested in getting published?”

“Yeah.” He turned half around on his stool. “How do you get poems published?”

“If I could really answer that, I would probably write a lot more poems than I do.”

“But you don’t have any problems now, about getting things in magazines and things?”

“Just about everything I write now—” Newboy folded his glass in both hands—“I can be sure will be published. It makes me very careful of what I actually put down. How careful are you?”

The first beer bottle was empty. “I don’t know.” He drank from the second. “I haven’t been a poet very long,” he confessed, smiling. “Only a couple of days. Why’d you come here?”

“What?” There was a little surprise there; but not much.

“I bet you know lots of writers, famous ones. And people in the government too. Why did you come here?”

“Oh, Bellona has developed…an underground reputation, you call it? One never reads about it, but one hears. There are some cities one must be just dying to visit.” In a theatrical whisper: “I hope this isn’t one of them.” While he laughed, his eyes asked forgiveness.

Kidd forgave and laughed.

“I really don’t know. It was a spur of the moment thing,” Newboy went on. “I don’t know how I did it. I certainly wasn’t expecting to meet anyone like Roger. That headline was a bit of a surprise. But Bellona is full of surprises.”

“You’re going to write about it here?”

Newboy turned his drink. “No. I don’t think so.” He smiled again. “You’re all safe.”

“You do know a lot of famous people though, I bet. Even when you read introductions and flyleaves and book reviews, you begin to figure out that everybody knows everybody. You get this picture of all these people sitting around together and getting mad, or friendly, probably screwing each other—”

“Literary intrigues? Oh, you’re right: It’s quite complicated, harrowing, insidious, vicious; and thoroughly fascinating. The only pastime I prefer to writing is gossip.”

He frowned. “Somebody else was talking to me about gossip. Everybody around here sort of goes for it.” Lanya was still not in the bar. He looked again at Newboy. “She knows your friend Mr. Calkins.”

“It is a small city. I wish Paul Fenster had felt a little less—up tight?” He gestured toward the notebook. “I’d enjoy seeing some of your poems.”

“Huh?”

“I enjoy reading poems, especially by people I’ve met. Let me tell you right away, I won’t even presume to say anything about whether I think they’re good or bad. But you’re pleasant, in an angular way. I’d like to see what you wrote.”

“Oh. I don’t have very many. I’ve just been writing them down for…well, like I say, not long.”

“Then it won’t take me very long to read them—if you wouldn’t mind showing them to me, sometime when you felt like it?”

“Oh. Sure. But you would have to tell me if they’re good.”

“I doubt if I could.”

“Sure you could. I mean I’d listen to what you said. That would be good for me.”

“May I tell you a story?”

Kidd cocked his head, and found his own eager distrust interesting.

Newboy waved a finger at the bartender for refills. “Some years ago in London, when I was much younger than the time between then and now would indicate, my Hampstead host winked at me through his sherry glass and asked if I would like to meet an American writer staying in the city. That afternoon I had to see an editor of an Arts Council subsidized magazine to which my host, the writer in question, and myself all contributed. I enjoy writers: their personalities intrigue me. I can talk about it in this detached way because I’m afraid I do so little of it myself now, that, though I presumptuously feel myself an artist at all times, I only consider myself a writer a month or so out of the year. On good years. At any rate, I agreed. The American writer was phoned to come over that evening. While I was waiting to go out, I picked up a magazine in which he had an article—a description of his travels through Mexico—and began the afternoon’s preparation for the evening’s encounter. The world is small: I had been hearing of this young man for two years. I had read his name in conjunction with my own in several places. But I had actually read no single piece by him before. I poured more sherry and turned to the article. It was impenetrable! I read on through the limpest recountings of passage through pointless scenery and unfocused meetings with vapid people. The judgments on the land were inane. The insights into the populace, had they been expressed with more energy, would have been a bit horrifying for their prejudice. Fortunately the prose was too dense for me to get through more than ten of the sixteen pages. I have always prided myself on my ability to read anything; I feel I must, as my own output is so small. But I put that article by! The strange machinery by which a reputation precedes its source we all know is faulty. Yet how much faith we put in it! I assumed I had received that necessary betrayal and took my carrier bag full of Christmas presents into London’s winter mud. The editor in his last letter had invited me, jokingly, to Christmas dinner, and I had written an equally joking acceptance and then come, two thousand miles I believe, for a London holiday. Such schemes, delightful in the anticipation and the later retelling, have their drawbacks in present practice. I’d arrived three days in advance, and thought it best to deliver gifts in time for Christmas morning and allow my host to rejudge the size of his goose and add a plum or so to his pudding. At the door, back of an English green hall, I rang the bell. It was answered by this very large, very golden young man, who, when he spoke, was obviously American. Let me see how nearly I can remember the conversation. It contributes to the point.

“I asked if my friends were in.

“He said no, they were out for the afternoon; he was babysitting with their two daughters.

“I said I just wanted to leave off some presents, and could he please tell them to expect me for dinner, Christmas day.

“Oh, he said. You must be—well, I’m going to be coming to see you this evening!

“I laughed again, surprised. Very well, I said, I look forward to it. We shook hands, and I hurried off. He seemed affable and I gained interest in the coming meeting. First rule of behavior in the literary community: Never condemn a man in the living room for any indiscretion he has put on paper. The amount of charity you wish to extend to the living-room barbarian because of his literary excellence is a matter of your own temperament. My point, however, is that we exchanged no more than seventy-five or a hundred words. Virtually I only heard his voice. At any rate, back at Hampstead, as sherry gave way for redder wine, I happened to pick up the magazine with the writer’s article. Well, I decided, I shall give it one more chance. I opened it and began to read.” Newboy glared over the rim, set down the glass without looking at it and pressed his lips to a slash. “It was lucid, it was vivid, it was both arch and ironic. What I had taken for banality was the most delicate satire. The piece presented an excruciating vision of the conditions under which the country struggled, as well as the absurdity of the author’s own position as American and tourist. It walked that terribly difficult line between grace and pathos. And all I had heard was his voice! It was retiring, the slightest bit effeminate, with a period and emphasis oddly awry with the great object of fresh water, redwoods, and Rockies who spoke with it. But what, simply, had happened was that now I could hear that voice informing the prose, supplying the emphasis here or there to unlock for me what previously had been as dense and graceless as a telephone directory. I have delighted in all of this writer’s work since with exquisite enjoyment!” Newboy took another sip. “Ah, but there is a brief corollary. Your critics here in the States have done me the ultimate kindness of choosing only the work of mine I find interesting for their discussions, and those interminable volumes of hair-splitting which insure a university position for me when the Diplomatic Service exhausts my passion for tattle, they let by. On my last trip to your country I was greeted with a rather laudatory review of the reissue of my early poems, in one of your more prestigious literary magazines, by a lady whom modesty forbids me to call incisive if only because she had been so generous with her praise. She was the first American to write of me. But before she ever did, I had followed her critical writings with an avidity I usually reserve only for poets. A prolific critic of necessity must say many absurd things. The test is, once a body of articles has passed your eye, whether the intelligence and acumen is more memorable than the absurdity. I had never met her. To come off a plane, pick up three magazines at the airport, and, in the taxi to the hotel, discover her article halfway through the second was a delight, a rarity, a pleasure for which once, in fantasy, I perhaps became a writer. And at the hotel, she had left a letter, not at the desk, but in my door: She was passing through New York, was in a hotel two blocks away, and wanted to know if I would meet her for a drink that evening, assuming my flight had not tired me out. I was delighted, I was grateful: what better creatures we would be if such attention were not so enjoyable. It was a pleasant drink, a pleasant evening: the relation has become the most rewarding friendship in the years since. It is rare enough, when people who have been first introduced by reputation can move on to a personal friendship, to remark it. But I noted this some days later, when I returned to one of her articles: Part of the measured consideration that informed her writing came from her choice of vocabulary. You know the Pope couplet: When Ajax strives some rock’s vast weight to throw, / The line too labours and the words move slow. She had a penchant for following a word ending in a heavy consonant with a word that began with one equally heavy. In my mind, I had constructed a considered and leisurely tone of voice which, even when the matter lacked, informed her written utterances with dignity. Using the same vocabulary she wrote with, I realized, on the evening we met, she speaks extremely rapidly, with animation and enthusiasm. And certainly her intelligence is as acute as I had ever judged it. But though she has become one of my closest friends, I lost practically all enjoyment in reading her. Even as I reread what before has given me the greatest intellectual pleasure, the words rush together in her vocal pattern, and all dignity and reserve has deserted the writing; I can only be grateful that, when we meet, we can argue and dissect the works before us till dawn, so that I still have some benefit of her astounding analytical faculty.” He drank once more. “How can I possibly tell if your poems are good? We’ve met. I’ve heard you speak. And I have not even broached the convolved and emotional swamp some people are silly enough to call an objective judgment, but merely the critical distortion that comes from having heard your voice.” Newboy waited, smiling.

“Is that a story you tell to everybody who asks you to read their poems?”

“Ah!” Newboy raised his finger. “I asked you if I might be allowed to read them. It is a story I have told to several people who’ve asked me for a judgment.” Newboy swirled blunted ice. “Everyone knows everyone. Yes, you’re right.” He nodded. “I wonder sometimes if the purpose of the artistic community isn’t to provide a concerned social matrix which simultaneously assures that no member, regardless of honors or approbation, has the slightest idea of the worth of his own work.”