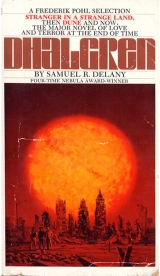

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“Hello, sir.” Glass put out his hand. “Glad to meet you.”

Kamp had to remember to shake. “What is…I mean?”

“Come on,” Kid said. “Let’s move over this way.”

“What’s going on now?” Kamp followed them. “Now, well…Roger gave me a list of places to hit this evening. I’m afraid I’m one of those guys who likes to drink booze and chase women—the Navy’s favorite kind. While that bar is all very interesting—a very interesting bunch—” he nodded—“really, I thought I might do better, at least on the second part of that, someplace. Like here.” He looked up at the balcony again, while a sudden mass of people moved noisily toward the door and out. “They got some pretty women, too…” Another bunch followed them. “What is it?” Kamp asked.

“Some crazy white folks with guns,” Kid said. “They aren’t doing anything but making people nervous. But they shouldn’t be up there, anyway.”

“Didn’t I hear somebody saying something about people getting shot in the street this afternoon?”

“Yeah,” Glass said, and grimaced.

“Oh,” Kamp said, because he could apparently think of nothing else. “Roger said they didn’t even let white people in this place. What are they doing here?”

Kid frowned a moment at Kamp. “Well, some of us get by.”

“Oh,” Kamp said again. “Well, sure. I mean…”

“You from the moon, ain’t you,” Glass said. “That’s pretty interesting.”

Kamp started to say something, but a voice—it was the Reverend’s—came through the half-silence that followed the exodus:

“…of the crossing taken again is not the value of the crossing? Oh, my poor, inaccurate hands and eyes! Don’t you know that once you have transgressed that boundary, every atom, the interior of every point of reality, has shifted its relation to every other you’ve left behind, shaken and jangled within the field of time, so that if you cross back, you return to a very different space from the one you left? You have crossed the river to come to this city? Do you really think you can cross back to a world where a blue sky goes violet in the evening, buttered over with the light of a single, silver moon? Or that after a breath of dark, presaged by a false, familiar dawn, a little disk of fire will spurt, spitting light, over trees and sparse clouds, women, men, and works of hand? But you do! Of course you do! How else are we to retain the inflationary coinage and cheap paper money of sanity and solipsism? Oh, it is common knowledge, the name of that so secondary moon that intruded itself upon our so ordinary night. But the arcane and unspoken name of what rose on this so extraordinary day, for which George is only consort, that alone will free you of this city! Pray with me! Pray! Pray that this city is the one, pure, logical space from which, without being a poet or a god, we can all actually leave if—what?” Someone reached up to her: the Reverend looked down. “What did…?” It was George. The Reverend bent. For a moment she started to look up, did not, and hastily climbed from her platform. Her small head was lost among the heads around her.

“Well, I guess it’s about time for me to get up to Roger’s then.” Kamp looked around. “Though they have some pretty nice-looking ladies around, I must admit.”

“Guess it’s time for us all to get going,” Kid said, and noticed Kamp did not move. He tried to glance in the direction Kamp looked, wondering which lady his eyes had come to rest on, found only the blank, barred window.

Kamp said: “Um…Getting up to Roger’s in the dark…” He shifted his weight, put his one hand in his slacks pocket. “I don’t really enjoy the idea.” He shifted back. “Say, you guys want a job?”

“Huh?”

“Give you five bucks if you walk me up to the house—you know where it is?”

Kid nodded.

“I mean, you guys are in the protection business, aren’t you? I’d just as soon have some, walking around this town at night.”

“Yeah?”

“Walking around the streets in the dark, in a city with no police, you don’t know what you’re going to find…both of you: I’ll give you five apiece.”

“I’ll go with you,” Glass said.

“We’ll go,” Kid said.

“I really appreciate that, now, I really do. I don’t want to rush you out. If you want to stay around and have a couple more drinks, fine. Just let me know when you’re ready—”

Glass looked at Kid with a sort of Is-he-crazy? look.

So Kid said, “We’ll go now,” and thought: Is he that much more terrified of the dark than known danger?

“Good,” Kamp said. “Okay. Fine, now.” He grinned and started for the crowded door.

Glass’s expression was still puzzled.

“Yeah,” Kid said. “He’s for real. He’s been to the moon.”

Glass laughed without opening his lips. “I’m for real too, man.” And then he clapped his hands.

Kamp looked back at them.

Kid, followed by Glass, shouldered through the bunch milling loudly at the exit.

In the hallway, Kamp asked, “Do you fellows—you’re scorpions, now, right?—do you fellows have much trouble around here?”

“Our share,” Glass said.

Kid thought: Glass always waits before he speaks as if it were my place to speak first.

“I’m not the sort of man who usually runs from a fight,” Kamp said, “But, now, you don’t set yourself up. I’m not carrying a lot of money, but I want to get home with what I’ve got.” (People before the door listened to a woman who, in the midst of her story, stopped to laugh torrentially.) “If I’m going to stay in Bellona for a while, maybe it would be a good idea to hire a bunch of you guys to hang around with me. Then again, maybe that would just be attracting attention. Now, I really do appreciate you coming with me.”

“We won’t let anything happen to you,” Kid said and wondered why.

He contemplated telling Kamp his fear was silly; and realized his own nether consciousness had grown fearful.

Glass settled his shoulders, and his chin, and his thumbs in his frayed pockets, like a black, drugstore cowboy.

“You’ll be okay,” Kid reiterated.

The woman recovered enough for the story’s punchline, which was “…the sun! He said it was the God-damn sun!” Black men and women rocked and howled.

Kid laughed too; they circuited the group, into the dark.

“Did you talk to George when you were inside?” Glass asked.

“We sort of talked. He offered me one of his girlfriends. But she just wasn’t my type, now. Now if he’d offered me the other one…” Kamp chuckled.

“What’d you think of him?” Kid asked.

“He isn’t so much. I mean, I don’t know why everybody is so scared of him.”

“Scared?”

“Roger’s terrified,” Kamp said. “Roger was the one who told me about him, of course. It’s an interesting story, but it’s strange. What do you think?”

Kid shrugged. “What’s there to say?”

“A great deal, from what you hear.”

On the brick wall, beneath the pulsing streetlamp, George’s posters, as shiny as if they had been varnished, overlapped like the immense and painted scales of a dragon, flank fading off and up into night. Glass looked at them as they passed. Kid and Kamp glanced at Glass.

“From what I’ve gathered, now, everybody spends a great deal of time talking about him.”

“What did you two talk about, beside swapping pussy?” Kid asked.

“He mentioned you, among other things.”

“Yeah? What did he say?”

“He wanted to know if I’d met you. When I said I had, he wanted to know my opinion of you. Seems people are almost as interested in you as they are in him.”

That seemed like something to laugh at. Kid was surprised at Kamp’s silence.

Dark pulled over Kamp’s face. “You know, there’s something—well, I’m not a strictly religious man. But I mean, for instance, when we were up there and we read the bible to everybody on television, we meant it. There’s something about naming a new moon, for somebody—somebody like that, and all that sort of stuff, now, it’s against religion. I don’t like it.”

Glass chuckled. “They ain’t named the sun yet.”

Kamp, baffled by Glass’s accent (by now Kid had set it somewhere near Shreveport), made him say that again.

“Oh,” Kamp said when he understood. “Oh, you mean this afternoon.”

“Yeah,” Glass said. “I hope you don’t think they gonna name it after you?” and chuckled on.

“You think you could live up to that?” Kid asked.

Kamp gestured in the dark. But they could not tell the curve of his arm, whether it were closed or open-handed, so lost the meaning. “You fellows know where we’re going, now?”

“We’re going right,” Glass said.

Kid felt distinctly they were going wrong. But distrust of his distinct feelings had become second nature. He walked, waiting, beside them.

“See,” Glass said, surprising Kid from his reverie, maybe twenty minutes later, “This is that place between Brisbain North and Brisbain South. Told you we’re going right.”

Two canyon walls collapsed inward upon one another, obliterating the time between.

“What?” asked Kamp.

“We’re going right,” Glass said. “Up to Mr. Calkins’.”

Lamps on three consecutive corners worked.

They squinted and blinked at one another after blocks of darkness.

“I guess,” Kamp said, jocularly, “it must be pretty hard for anybody to navigate after dark in the city.”

“You learn,” Kid said.

“What?”

What sort of accent do I have? “I said ‘You learn.’”

“Oh.”

Ahead, black was punctured by a streetlamp at least five blocks off, flickering through branches of some otherwise invisible tree.

“You fellows ever have any trouble on the street?”

“Yeah,” Kid said.

“What part of the city,” Kamp asked. “You know, I want to know what neighborhoods to stay out of. Was it over where we were? The colored area, Jackson?”

“Right outside of Calkins’,” Kid said.

“Did you get robbed?”

“No. I was just minding my own business. Then this bunch of guys jumped out and beat shit out of me. They didn’t have anything better to do, I guess.”

“Did you ever find out who it was?”

“Scorpions,” Kid said. (Glass chuckled again.) “But that was before I started running.”

“Scorpions are about the only thing in Bellona you got to worry about,” Glass said. “Unless it’s some nut with a rifle in an upstairs window or on the roof who decides to pick you off.”

“—because he doesn’t have anything better to do,” Kid finished.

Kamp took a breath in the dark. “You say the neighborhood up here, around Roger’s, is really bad?”

“About as bad as anyplace else,” Kid said.

“Well,” Kamp reflected, “I guess it was a pretty good idea to get you guys to come up with me, now.”

He is using his fear to use me, Kid reflected, and said nothing. Ten dollars for the walk? Kid wondered how much this paralleled the genesis of the protection racket in the park commune. He put his fingertips in his pockets, hunched his shoulders, grinned at the night and thought: Is this how a dangerous scorpion walks? He swung his steps a bit wider.

Kamp coughed, and said very little for the next quarter-hour.

…am a marauder in the internal city, tenuous as the dark shaken on itself with a footstep, eyeblink, heartbeat. Intrigued by the way his fear has given me purpose, I swagger down the labyrinth of least resistance. (Where is the sound?) There is a sound like glass and sand, or a finger turning in the channels of the ear. I acknowledge my own death with an electrified tongue, wanting to cry. These breaths I leave here disperse like apparitions of laughter I am too terrified to release.

Which was the conclusion of the reverie he’d begun before: but could not remember its beginning.

“Do you know how far along the wall here the gate is?” Kamp asked.

“The wall makes your voice sound funny in the dark, don’t it?” Glass said.

“Won’t we be able to see some light from the house?” Kamp asked.

Kid asked: “They still got light?”

They walked.

“There,” Kid said. “I see something—” stumbling at the curb edge. “…hey, watch—!” but did not fall. He recovered to Kamp’s nervous laugh. He thinks, Kid thought, something almost jumped out at us. Only my eyes are bandaged in darkness. The rest of my body swerves in light.

“Yes,” Kamp said. “We’re here.”

Between the newels, through the brass bars and shaggy pine, light slid into the crevices of Glass’s face (sweating; Kid was surprised) and dusted Kamp’s that was simply very pale.

I thought I was the only one scared to death, Kid thought. My luck, on my dumb face it doesn’t show.

“José,” Kamp called. “José, it’s Mike Kamp. I’m back for the night. José,” Kamp explained somewhat inanely, “is the man Roger has on the gate.”

K-k-klank: the lock (remotely controlled?) opened and bars swung inches in.

“Well,” Kamp put his hands in his pockets. “I certainly want to thank you guys for—Oh.” His hands came out. “Here you go.” He riffled through his wallet, held it up to his eyes. “Got to see what I have here, now…” He took out two bills.

Glass said, “Thanks,” when he got his.

“Well,” Kamp said again. “Thanks again. Well now. If I don’t see you before, Kid, I’ll see you in three Sundays.” He pushed the gate. “Do you fellows want to come—”

“No,” Kid said, and realized Glass had gotten himself ready to say yes.

“All right.” K-k-klank. “Good night now.”

Glass shifted from one foot to the other. “Night.” Then he said: “Those curbs are too much in all this dark shit. Let’s go down the middle of the street.”

“Sure.”

They stepped off the sidewalk and started back.

You’ll get to see what it looks like inside in a couple of weeks, Kid thought of saying and didn’t. He also thought of asking why Glass was a scorpion, how long he’d been, and what he’d done before.

They did not talk.

Kid constructed the stumps of a dozen conversations, and heard each veer into some mutually embarrassing area, and so abandoned it. Once it occurred to him Glass was probably indulging in the same process: for a while he pondered what Glass might want to know about him: that too became fantasized converse and, like the others, embarrassing. So their silent intercourse moved to another subject.

“All this walking ain’t worth five bucks,” Glass said at the North-South connection.

“Here.” Kid held out his bill, crumpled by the time in his fist (the crisp points had blunted with perspiration). “It probably ain’t worth ten either. But I don’t need it.”

“Thanks,” Glass said. “Hey, thanks, man.”

He was both surprised and amused that the interchange released him from his preoccupation with who Glass was.

They ambled the black street into the city, neither moving to illuminate his projector, in memoriam—Kid realized—to the sun.

How long had they been? Three hours? More? The distance between then and now was packed full of time during which his furious mind had prodded the outsides of a myriad fantasies and (if he were asked he would have said) nothing had happened. Thoughts of madness: Perhaps those moments of miscast reality or lost time were the points (during times when nothing happened) when the prodding broke through. The language that happened on other muscles than the tongue was better for grasping these. Things he could not say wobbled in his mouth, and brought back, vividly in the black, how at age four he had sat in the cellar, putting into his mouth, one after the other, blue, orange, and pink marbles, to see if he could taste the colors.

They passed another lamp.

Glass’s face was dry.

The way anywhere in this city was obviously to drift; Kid drifted, on kinesthetic memory. To try consciously for destination was to come upon street signs illegible through smoke, darkness, or vandalism, wrongly placed, or missing.

When they crossed Jackson, Kid said, “I want to go back to the party.”

“Sure, motherfucker.” Glass grinned. “Why not? You really want to?”

“Just to see what happened.”

Glass sighed.

Across the pavement, at the other end of the block, Kid saw the dim trapezoid. “Light’s still on.”

Of the cluster of three lanterns inside the door, one still burned. Inside, the doors to the hall were closed.

“Don’t sound like nobody’s there.”

“Open the door,” Kid said because Glass was ahead of him.

Glass pushed, stepped in; Kid stepped after.

Only two lanterns were working: a third, in the corner, guttered. The meeting room was empty; the party’s detritus lay in ruin and shadow.

Near the one-winged statue, fallen among the prickly plants, the tip of the barrel on his belly, the butt on the linoleum, the black guard whom they had talked to outside lay on his back and snored. The tracked plaster, overturned chairs, and scattered bottles momentarily brought Kid an image of a drunken shooting, the barrel swinging around the room moments before he’d passed out—but he saw no bullet holes.

He could see no one in the balcony.

On a chair by the far wall, muffled in an absurd overcoat, the only other person in the room swayed to one side, froze, recovered, swayed once more, once more froze at an angle that challenged gravity.

“What does he have inside him, a gyroscope?” Glass asked.

“More like half a spoon of skag.”

Glass laughed.

In the hallway, a door that had been closed before now stood ajar on a stairwell.

“You wanna go exploring?” Glass asked.

“Sure,” Kid said.

Glass pinched at his broad nose, twice, sucked in both lips, cleared his throat, and started down.

Kid followed.

A door at the bottom was open. Kid’s foot crushed a Times, which caught some low draft (the dirty stair was cold: the banister pipe warm) and drifted down. It rasped again beneath his boot on the last step.

Kid came up behind Glass in the doorway:

The couch had been opened into a bed. The gaunt, brick-haired girl who had been with George, her neck looped with the optical chain, slept beneath a rumpled blanket, baring small, light-coffee breasts, dolloped with dark nipples.

A lamp by the bed had a shade of glass from which a triangle was broken away. The wedge of light, molding to body and bedding, just touched one aureole at the height of her blowy breath.

“Hey, man!” Glass whispered, and grinned.

Kid breathed with her, swaying on the bottom step, and had to move his feet apart.

“How’d you like some of that?”

“I think I could eat about three helpings,” Kid said. “Where’s George?”

“Man, he probably gone off with the other one—” Glass’s emphatic whispers broke into and returned from falsetto.

Then: “What the fuck are you doing!” She sat up, sharply, face going from sleep to anger like two frames of film.

“Jesus Christ, lady,” Kid said, “we were just looking.”

“Well stop looking! Go on, get the fuck out of here! Where the hell is everybody? You, both of you, get out!”

“Sweetheart, don’t go on like that,” Glass said. “Now you got your door wide open—”

“Did that nut leave the damn door unlocked—” She pulled up the sheet, reached down by the bed, and whipped up some article of clothing. “Come on. Out! Out! Out! I’m not kidding. Out!”

“Look—” Kid glumly contemplated the difficulties of rape (a surprising memory of his arms filled with the bloody boy; he moved his feet back together) and wondered what Glass was contemplating—“if you just stop yelling, maybe we can discuss this a little; you might change your mind—”

“Not on your fucking life!” She shook out the wrinkled jump suit, swung her legs off the bed, and stuck her feet in. “I don’t know what you got on your mind to do. But if you try it, you gonna get your ass hurt!”

“Nobody wants to hurt anybody—” Kid stopped because Glass was looking up at the small, high window. Kid felt his cheeks wrinkling and the pressure of surprise on his forehead.

She started to say something, and then said, “Huh?”

The foggy air outside had lightened to blue.

Then Glass turned and ran up the stairs.

“Hey!” Kid followed him.

Behind, he could hear her fighting with shoes.

Kid ran down the hall, swung outside.

Glass, a dozen feet from the sidewalk, stared along the street.

Kid joined him, stopping to look back, at the sound of footsteps: She stopped at the edge of the door, leaned out, her face contorted. “Jesus God,” she said softly, stepped out and raised her head. “…it’s getting…light!”

Kid’s first thought was: It’s happening too fast. The uneven roofs descended in a paling V, vertex blurred with smoke. He stared, waiting for an eruption of bronze fires. But no; the arch of visible sky, though modeled and mottled with billows, was deep blue, except the lowest quarter, gone grey.

“Oh, man!” Glass looked at Kid. “I’m so tired.” Below one eye, water tracked his dark cheek. Blinking, Glass turned back to the morning.

Kid got chills. And kept getting them. I don’t trust this reaction, he thought, remembering the last late-night TV drama where the frail heroine’s tearful realizations of burgeoning love had caused him the same one. I’m going on like this because there’s a nigger next to me about to bawl, and another in the doorway who looks so scared and confused I’m about to…No, it’s not the light. No.

But the chills came on, frazzling his flesh, till even his thoughts stuttered. Chills sandpapered his spine. His palms hummed. He opened his mouth and eyes and his fingers wide to the raddled and streaming dawn.

5

Sunday, April 1, 1976—There is reason to speak of this on page two rather than lend the phenomenon the leading headline it could so easily claim. We, for one, are just not ready to grant the hysteria prevailing beneath this miasmal pollution the reinforcement of our shock.

We saw this one ourselves.

But in the city where we live, one doubts even the validity of that credential.

We went so far as to entertain awhile the idea of devoting this issue to accounts only by those who had slept through, who were busy in the cellar or windowless back room when, or—hope on hope—could claim to have been strolling about yesterday afternoon and observed during, nothing extraordinary in the sky.

But if the advent in our nights of George is anything to go by, we should have to look outside our misty and deliquescent city limits to find a negative witness. At least we hope so.

Please, return to page one. The plight of Jackson’s Lower Cumberland area, where apparently all power has gone out with the breaking of the water main on my last Thursday (how dangerous that is for the rest of us nobody can say because nobody can estimate the losses from the fractured dam in terms of our decreased population), is a real dilemma. More real, we would like to feel, than yesterday’s portent.

We are not anxious either to describe or even name what passed. Presumably some copy of this will get beyond our border; we should like to keep our good name. We would much prefer to give our opinions on Lower Cumberland Park. But another writer (page one, continued page seven) has already rehearsed his eyewitness, first-hand account. And, anyway, in his words, “…chances are, no one lives there anymore.”

Dubious to time, the arc became visible in the late afternoon of the overcast day. In a spectrum ranging only through grey, black, and blue, you would have to see to judge the effects of those golds and bronzes, those reds and purplish browns! Minutes later, most of us here had gathered in the August Garden. The view was awesome. Speculation, before awe silenced it, was rampant. When, after fifteen minutes, perhaps a fourth of the disk had emerged, we had our first case of hysteria…But rather than dwell on those understandable breakdowns, let us commend Professor Wellman on his level-headedness throughout, and Budgie Goldstein on her indomitable high spirits.

More than an hour in the rising, the monumental…disk? sphere? whatever? eventually cleared the visible buildings. There is some question, even among those gathered in August, as to whether the orb actually hovered, or whether it immediately changed direction and began to set again, slightly (by no more than a fifth of its diameter) to the left—this last, the estimate of Wallace Guardowsky.

The lower rim, at any rate, was above the horizon for fifteen or twenty minutes. Even at full height, it could be stared at for minutes because of the veiling clouds. Colonel Harris advised, however, that we curtail prolonged gazing. The setting, almost all are agreed, took substantially less time than the rising, and has been estimated between fifteen minutes and a half an hour. We have heard several attempts now, to estimate size, composition, and trajectory. We doubt recording even the ones we could understand would be much use—the merest indulgence in cleverness before something so…awful! Do we hear objections from you eager for meaningful cosmologic distractions? May we simply ask your trust: Of the explanations heard, none, frankly, was that clever. And we do not choose to insult our readers.

We recall, with distrust and wheedling astonishment, the speed at which the last such celestial apparition acquired, by common consent of the common, its cognomen. How heartening, then, that this vision should prove too monstrous for facile appellation. (One has been suggested from a number of quarters, but all common decency and decorum forbids us to mention it; we have defamed the young woman, many feel, enough in these pages already.) Indeed, though a label might cling to such when we review it with a smile, certain images lose their freedom and resonance if, when we regard them with a straight face, we do so through the diffraction of a name.

“What do you think of that?” Faust asked, coming a little ways across the street.

Kid laughed. “Calkins is pretty quick to call a spade a spade. But when it comes to naming anything else, he’s still chicken-shit!”

“No, no. Not that.” Faust had to toss the rolled paper three times before getting it into the second story window. “I mean on page one.”

Kid, sitting on the stoop, leaned down to scratch his foot. “What—?” He turned back to the front of the tabloid. “Where is Cumberland Park, anyway?”

“Lower Cumberland Park?” Faust craned his ropy neck and, beneath his corduroy jacket, scratched his undershirt. “That’s down at the other end of Jackson. That’s where they got some really bad niggers. It’s where the great god Harrison lives.”

“Oh,” Kid said. “Where I was last night. It says here something about nobody living there anymore.”

Faust hefted the bundle on his hip. “Then all I know is that I leave a God-damn lot of papers in front of a God-damn lot of doors, and they ain’t there the next day when I come back. Damn, splashing around in all that water in the street yesterday morning!” He squinted back at the window. “It was better this morning though. Hey, I see you again tomorrow. That your book the office is full up with?”

“I don’t know,” Kid said. “Is it?”

Faust frowned. “You should come up to the office sometime and take a look where they print the paper and things. Come up with me, some day. I’ll show it all to you. Your book went in the day before yesterday—” Faust snapped his fingers. “And I put cartons of it in the bookstores last night. Soon as it…well, you know, got dark.”

Kid grunted and opened the Times again, to look at something not Faust.

“Get your morning paper!” The old man loped down the block, hollering into the smoke: “Right here, get your morning paper!”

What he’d opened to was another quarter-page advertisement for Brass Orchids. He left it on the stoop, and walked toward the corner, when a sound he’d been dimly aware of broke over the sky: Roaring. And nestled in the roar, the whine a jet makes three blocks from the airport. Kid looked as the sound gathered above him. Nothing was visible; he looked down the block. Faust, a figurine off in a milky aquarium, had stopped too. The sound rolled away, lowering.

Faust moved on to disappear.

Kid turned the corner.

It’s different inside the nest, he thought, trying to figure what should be the same:

The crayoning on the dirty wall—

The loose ceiling fixture—

In his hand, the knob’s squared and toothy shaft rasped out another inch—

A black face came from the middle room, looked back inside; shook his head, and went down to the bathroom. Among voices, Nightmare’s laugh, and:

“Okay. I mean, okay.” That was Dragon Lady. “You said your thing, now what you want us to do?”

While someone else in the hubbub, shouted, “Hey, hey, hey come on now. Hey!”

“I mean now…yeah!” Nightmare’s voice separated. “What do you want?”

Kid went to the door.

Across the room, Siam and Glass noticed him with small, different nods. Kid leaned on the jamb. The people in the center, their backs to him, were not scorpions.

“I mean—” Nightmare, circling, bent to hit his knees—“what do you want?”

“Look.” John turned to follow him, holding the lapels of his Peruvian vest. “Look, this is very serious!” His blue work shirt was rolled up his forearms; the sleeves were stained, dirty, and frayed at one elbow. His thumbnails, the only ones visible, were very clean. “I mean you guys have got to…” He gestured.

Milly stepped out of the way of his arm.

“Gotta what?” Nightmare rubbed his shoulder. “Look, man I wasn’t there. I didn’t know nothing about it.”

“We were someplace else.” Dragon Lady turned a white cup in her dark hands, shoulders hunched, sipping, watching. “We weren’t even anywhere around, you know?” She alone in the room drank; and drank loudly.

Mildred brushed away threads of red hair and looked much older than Dragon Lady. (He remembered once thinking when neither were present that, for all their differences, they were about the same age.) Dragon Lady’s lips kept changing thickness.

“This is shit!” Nightmare kneaded his arm. “I mean this is real shit, man! Don’t load this shit on me. You want to talk to somebody—” His eyes came up beneath his brows and caught Kid—“talk to him. He was there, I wasn’t. It was his thing.”

Kid unfolded his arms. “What’d I do?”

“You—” Mildred turned—“killed somebody!”

He felt, after moments, his forehead wrinkle. “Oh yeah?” What cleared inside was distressingly close to relief. “When?” he asked with the calm and contrapuntal thought: No. No, that’s not possible, is it? No.

“Look,” John said, and looked between Nightmare and Kid. “Look, we could always talk to you guys, right? I mean you’re pretty together, you know? Nightmare, we’ve always done right by you, hey? And you’ve done right by us. Kid, you used to eat with us all the time, right? You were almost part of our family. We were gonna put you up the first night you got here, weren’t we? But you guys can’t go around and murder people. And expect us to just sit around. I mean we have to do something.”

“Who’d we kill?” he asked, realizing, they don’t mean me! They mean us. The feeling came cold and with loss.