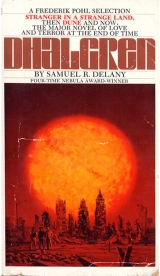

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“There’re probably people there,” Kidd said uncomfortably. “Probably a skeleton staff. Madame Brown and I were talking about that. It’s probably like at…the Management office.”

“Ah.” Her hands met in her lap. “Yes.” She sat back. “But I’m only telling you how it feels. To me. When the smoke thins, I can look across at the other buildings. So many of the windows are broken. Maybe the maintenance men in Arthur’s office have already started putting in new panes. The maintenance is always better in a place of business. Well, there’s more money involved. I just wonder when we can expect some sort of reasonable return to normal here. There’s a certain minimum standard that must be kept up. They should send somebody around, if only to let us know what the situation is. Not knowing, that’s the worst. If I did know something, something for sure about plans for repairing the damages, for restoring service, lights, and things, when we could expect them to start…” She looked oddly annoyed.

“Maybe they will,” he suggested, “send somebody around.”

“You’d think they would. We have had trouble with them before; there was a huge crack, it opened up in June’s ceiling. It wasn’t our fault. Something upstairs leaked. It took them three months to send somebody. But they answered my letter right away. Meanwhile, I just have to muddle, muddle on. And every morning I send Arthur out of here, out into that.” She nodded. “That’s the crime. Of course I couldn’t keep him back; he wouldn’t stay. I’d tell him how dangerous I thought it was out there, all the awful things I’m afraid might happen, and he’d—Oh, I wish he’d laugh. But he wouldn’t. He’d scowl. And go. He goes away, every morning, just disappears, down Forty-Fourth. The only thing I can do for him is try and keep a good home, where nothing can hurt him, at least here, a happy, safe, and—”

He thought she’d seen something behind him, and was about to turn around. But her expression went on to something more violent than recognition.

She bent her head. “I guess I haven’t done that very well. I haven’t done that at all.”

He wished she would let him leave.

“Mrs. Richards, I’m going to see about that stuff in the back.” He thought there was some stuff in the back still to be put in place. “You just try and take it easy now.” He got up, thinking: When I come back I can put down the living-room rug.

There’s nothing I can do, he justified, to sponge up her grief. And I can’t do nothing.

He opened the door to Bobby’s room where the furniture had still not been put against the walls.

And June’s fists crashed the edges of the poster together.

“Hey, I’m sorry…I didn’t realize this was your—” But it was Bobby’s room. Kidd’s apologetic smile dropped before her astounded despair. “Look, I’ll leave you alone…”

“He was going to tell!” she whispered, wide-eyed, shaking her head. “He said so! But I swear,” and she crushed the poster altogether now. “I swear I didn’t do it on purpose…!”

After a few moments, he said, “I suppose that’s the first thing that would have occurred to anybody else in his right mind. But I didn’t even think of it till just now.” Then—and was afraid—he backed out of the room and closed the door, unable to determine what had formed in her face. I’m just an observer, he thought, and, thinking it, felt the thought crumple like George’s poster between June’s fists.

Walking toward the living room, he envisioned her leaping from the door, to bite and rake his back. The doors stayed closed. There was no sound. And he didn’t want to go back to the living room.

Just as he came in, the lock ratcheted, and the hall door pushed open. “Hello, guess who I found on the way up here?”

“Hi, Mary.” Madame Brown followed Mr. Richards in.

“Honey, what in the world is that mess down in the lobby? It looks as though somebody—”

Mrs. Richards turned around on the couch.

Mr. Richards frowned.

Madame Brown, behind him, suddenly touched her hand to her bright, jeweled chains.

Mrs. Richards squeezed the fabric of her skirt. “Arthur, this afternoon Bobby…June—Bobby—”

His eyelids snapped wide enough to pain the sockets. He rolled, scrabbling on snarled blankets and crushed leaves, flung his hands at her naked back. Had he nails, he would have torn.

“Unnnh,” Lanya said and turned to him. Then, “Hey—” because he dragged her against him. “I know,” she mumbled beside his ear, moving her arms inside his to get them free, “you want to be a great and famous—”

His arms shook.

“Oh, hey—!” Her hands came up across his back, tightened. “You were having bad dreams! About that boy!”

He shook his head beside hers.

“It’s all right,” she whispered. She got one hand high enough to rub the back of his shoulder. “It’s all right now. You’re awake.” He took three rough breaths, with stomach-clenched silences between, then let go and rolled to his back. The red veil, between him and the darkness, here, then there, fell away.

She touched his arm; she kneaded his shoulder. “It was a really bad dream, wasn’t it?”

He said, “I don’t…know,” and stopped gasping. Foliage hung over them. Near the horizon, blurred in fog, he saw a tiny moon; and further away, another! His head came up from the blanket—went slowly back:

They were two parklights which, through smoke, looked like diffuse pearls. “I can’t remember if I was dreaming or not.”

“You were dreaming about Bobby,” she said. “That’s all. And you scared yourself awake.”

He shook his head. “I shouldn’t have given her that damned poster—”

Her head fell against his shoulder. “You didn’t have any way to know…” Her hand dropped over his chest; her thigh crossed his thigh.

“But—” he took her hand in his—“the funny lack of expression Mr. Richards got when she was trying to tell him how it happened. And in the middle of it, June came in, and sort of edged into the wall, and kept on brushing at her chin with her fist and blinking. And Mrs. Richards kept on saying, ‘It was an accident! It was a terrible accident!’ and Madame Brown just said ‘Oh, Lord!’ a couple of times, and Mr. Richards didn’t say anything. He just kept looking back and forth between Mrs. Richards and June as though he couldn’t quite figure out what they were saying, what they’d done, what had happened, until June started to cry and ran out of the room—”

“It sounds awful,” she said. “But try to think about something else—”

“I am.” He glanced at the parklights again; now there was only one. Had the other gone out? Or had some tree branch, lifted away by wind, settled back before it. “About what George and you were saying yesterday—about everybody being afraid of female sexuality, and trying to make it into something that wreaks death and destruction all about it. I mean, I don’t know what Mr. Richards would do if he found out his sunshine girl was running around the streets like a bitch in heat, lusting to be brutalized by some hulking, sadistic, buck nigger. Let’s see, he’s already driven one child out of the house with threats of murder—”

“Oh, Kidd, no…”

“—and the sounds that come out of that apartment when they don’t think anybody’s listening are just as strange as the ones that come up from Thirteen’s, believe me. Maybe she’s got good reason not to want her old man to know, and if Bobby was threatening, in that vicious way younger brothers can have, to show the poster to her parents, well maybe just for an instant, when she was backing him down the hall, and the door rolled open, from some sort of half-conscious impulse, it was easier to shove—or not even to shove, but just not say anything when he stepped back toward the wrong—”

“Kid,” Lanya said, “now come on!”

“It would be just like the myth: her lust for George, death and destruction! Only—only suppose it was an accident?” He took another breath. “That’s what frightens me. Suppose it was, like she said, just an accident. She didn’t see at all. Bobby just backed into the wrong shaft door. That’s what terrifies me. That’s the thing I’m scared of most.”

“Why…?” Lanya asked.

“Because…” He breathed, felt her head shift on his shoulder, her hand rock with his on his chest. “Because that means it’s the city. That means it’s the landscape: the bricks, and the girders, and the faulty wiring and the shot elevator machinery, all conspiring together to make these myths true. And that’s crazy.” He shook his head. “I shouldn’t have given her that poster. I shouldn’t. I really shouldn’t—” His head stopped shaking. “Motherfucker still hasn’t paid me my money. I was going to talk to him about it this evening. But I couldn’t, then.”

“No, it doesn’t sound like the most propitious time to bring up financial matters.”

“I just wanted to get out of there.”

She nodded.

“I don’t want the money. I really don’t.”

“Good.” She hugged. “Then just forget about the whole thing. Don’t go back there. Let them alone. If people are busy living out myths you don’t like, leave them to it.”

He raised his hand above his face, palm up, moving his fingers, watching them, black against four-fifths black, his arm muscle tiring, till he let his knuckles fall against his forehead. “I was so scared…When I woke up, I was so scared!”

“It was just a dream,” she insisted. And then: “Look, if it really was an accident, your bringing that poster didn’t have anything to do with it. And if she did do it on purpose, then she’s so far gone there’s no way you could possibly blame yourself!”

“I know,” he said. “But do you think…” He could feel the place on his neck her breath brushed warmly. “Do you think a city can control the way the people live inside it? I mean, just the geography, the way the streets are laid out, the way the buildings are placed?”

“Of course it does,” she said. “San Francisco and Rome are both built on hills. I’ve spent time in both and I’m sure the amount of energy you have to spend to get from one place to the other in either city has more to do with the tenor of life in each one than whoever happens to be mayor. New York and Istanbul are both cut through by large bodies of water, and even out of sight of it, the feel on the streets in either is more alike than either one is to, say, Paris or Munich, which are only crossed by swimmable rivers. And London, whose river is an entirely different width, has a different feel entirely.” She waited.

So at last he said. “Yeah…But thinking that live streets and windows are plotting and conniving to make you into something you’re not, that’s crazy, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” she said, “that’s crazy—in a word.”

He slid his arm around her and could smell her wake-up breath, cuddling her. “You know, when I pulled him out, blood all over me, like a flayed carcass off a butcher hook…you know, I had half a hard-on? That’s too much, huh?”

She reached between his legs. “You still do.” She moved her fingers there; he moved in her fingers.

“Maybe that’s what I was dreaming about?” He laughed sharply. “Do you think that’s what I was—?”

Her hand contracted, released, moved forward, moved back.

He said: “I don’t think that’s going to do any good…”

Against his chest he felt her shrug. “Try.”

Not so much to his surprise, but somehow against his will, his will ceased, and it did.

I let my head fall back in this angry season. There, tensions I had hoped would resolve, merely shift with the body’s machinery. The act is clumsy, halting, and without grace or reason. What can I read in the smell of her, what message in the code of her breath? This mountain opens passages of light. The lines on squeezed lids cage the bursting balls. All efforts, dying here, coalesce in the blockage of ear and throat, to an a-corporal lucence, a patterning released from pleasure, the retained shadow of pure idea.

The leaf shattered in his blunt fingers: leaf and flesh—he ground the flakings with his roughened thumb—were the same color, a different texture. He stared, defining the distinction.

“Come on.” Lanya caught up his hand.

Flakes fluttered away (some he felt cling); notebook under his arm, he stood up from where he’d been leaning on the other end of the picnic table. “I was just thinking,” Kidd said, “maybe I should stop off at the Labrys and try to collect my money.”

“And keep Mr. Newboy waiting?” Lanya asked. “Look, you said you got them all moved!”

“I was just thinking about it,” Kidd said. “That’s all.”

A young man with a high, bald forehead and side hair to his naked shoulders sat on an overturned wire basket, one sandal resting over the other. He leaned forward, a burned twig in each hand. They had smudged his fingers. “I take these from you crossed,” he said to a girl sitting Indian fashion on the ground before him, “and give them to you crossed.”

The girl’s black hair was pulled back lacquer tight, till, at the thong whipped a dozen times around her pony tail and tied, it broke into a dozen rivulets about the collar of her pink shirt: her sleeves were torn off; frayed pink threads lay against her thin arms. With her own smudged fingers, she took the twigs. “I take these from you—” she hesitated, concentrated—“uncrossed and I give them to you—” she thrust them back—“uncrossed?”

Some spectators in the circle laughed. Others looked as bemused as she did.

“Nope. Got it wrong again.” The man spread his feet, sandal heels lining the dirt, and drew them back against the basket rim. “Now watch.” With crossed wrists he took the sticks from her: “I take these from you…uncrossed—” his wrists came apart—“and I give them back to you…”

John, scratching under the fringed shoulder of his Peruvian vest with one hand and eating a piece of bread with the other, came around the furnace. “You guys want some more?” He gestured with the slice, chewing. “Just go take it. You didn’t get here till we were already halfway through breakfast.” Gold-streaked hair and gold wire frames set off his tenacious tan; his pupils were like circles cut from the overcast.

Kidd said: “We had enough. Really.”

In the basket on which the bald man sat (“I take these from you uncrossed and I give them to you…crossed!” More laughter) a half dozen loaves of bland, saltless bread had been brought over by two scorpions who had taken back two cardboard cartons of canned food, in exchange.

Kidd said: “You’re sure that’s today’s paper?” which was the third time he’d asked John that over the last hour.

“Sure I’m sure.” John picked the paper up off the picnic table. “Tuesday, May 5th—that’s May-day, isn’t it?—1904. Faust brought it by this morning.” He folded it back, began to beat it against his thigh.

“Tell Milly when she gets back thanks again for the clean shirt.” Lanya tucked one side of the rough-dried blue cotton under her belt. “I’ll bring it back later this afternoon.”

“I will. I think Mill’s laundry project—” John mused, beating, munching—“is one of the most successful we’ve investigated. Don’t you?”

Lanya nodded, still tucking.

“Come on,” Kidd said. “Let’s get going. I mean if this is really Tuesday. You’re sure he said Tuesday now?”

“I’m sure,” Lanya said.

(“Nope, you’re still doing it wrong, now watch: I take them from you crossed and I give them to you uncrossed.” His fingers, smudged to the second knuckle and bunched at the base of the charred batons, came forward. Hers, smeared equally, hesitated, went back to fiddle with one another, started to take them again. She said: “I just don’t get it. I don’t get it at all.” Fewer laughed this time.)

“So long,” Kidd said to John, who nodded, his mouth full.

They made their way through the knapsacks.

“That was nice of them to feed us…again,” he said. “They’re not bad kids.”

“They’re nice kids.” She brushed at her clean, wrinkled front. “Wish I had an iron.”

“You really have to get dressed up to go visit Calkins’ place, huh?”

Lanya glanced appraisingly at his new black jeans, his black leather vest. “Well, you’re practically in uniform already. I, unlike you, however, am not at my best when scruffy.”

They made their way toward the park entrance.

“What’s the laundry project?” he asked. “Do they have some place where they pound the clothes with paddles on a rock?”

“I think,” Lanya said, “Milly and Jommy and Wally and What’s-her-name-with-all-the-Indian-silver found a laundromat or something a few days ago. Only the power’s off. Today they’ve gone off to find the nearest three-pronged outlet that works.”

“Then when did the one you have on get done?”

“Milly and I washed a whole bunch by hand in the ladies’ john yesterday, while you were at work.”

“Oh.”

“Recording engineer to laundress,” Lanya mused as they passed through the lion gate, “in less than a year.” She humphed. “If you asked him, I suspect John would tell you that’s progress.”

“The paper says it’s Tuesday.” Kidd moved his thumb absently against the blade of his orchid he’d hooked through a side belt loop; inside it, the chain harness jingled, each step. “He said come up when the paper said it was Tuesday. You don’t think he’s forgotten?”

“If he has, we’ll remind him,” Lanya said. “No, I’m sure he hasn’t forgotten.”

He could press his thumb or his knuckles against the sharp edges and leave only the slightest line, that later, like the other cross-hatches in the surface skin, would fill with dirt; but he could hardly feel it. “Maybe we’ll avoid any run-ins with scorpions today,” he said as they crossed from Brisbain North to Brisbain South. “If we’re lucky.”

“No self-respecting scorpion would be up at this hour of the morning,” Lanya said. “They all sleep till three or four, then carouse till dawn, didn’t you know?”

“Sounds like the life. You been in Calkins’ place before, you keep telling me. It’ll be okay?”

“If I hadn’t been in there before—” she slapped her harmonica on her palm—“I wouldn’t be making this fuss.” Three glistening notes. She frowned, and blew again.

“I think you look pretty good scruffy,” he said.

She played more notes, welding them nearly into melody, till she changed her mind, laughed, or complained, or was silent, before beginning another. They walked, Lanya strewing incomplete tunes.

His notebook flapped his hip. (His other hand was petaled in steel, now.) He swung, in twin protections, from the curb. “I wonder if I’m scared of what he’s going to say.”

Between notes: “Hmm?”

“Mr. Newboy. About my poems. Shit, I’m not going to see him. I want to see where Calkins lives. I don’t care what Mr. Newboy says about what I write.”

“I left three perfectly beautiful dresses there, upstairs in Phil’s closet. I wonder if they’re still there.”

“Probably, if Phil is.”

“Christ, no. Phil hasn’t been in the city for…weeks!”

The air was tingly and industrial. He looked up on a sky here the color of clay, there the color of ivory, lighter over there like tarnished tin.

“Good idea,” Lanya said, “for me to split. I got you.” Slipping her hand between blades, she grasped two of his fingers. Even on her thin wrist, turned, the blades pressed, rubbed, creased her skin—

“Watch out. You’re gonna…”

But she didn’t.

Over the wall hung hanks of ivy.

At the brass gate, she said, “It’s quiet inside.”

“Do you ring?” he asked, “or do you shout?” Then he shouted: “Mr. Newboy!”

She pulled her hand gingerly away. “There used to be a bell, I think…” She fingered the stone around the brass plate.

“Hello…” from inside. Footsteps ground the gravel somewhere behind the pines.

“Hello, sir!” Kidd called, pulling the orchid off, pushing a blade into a belt-loop.

Ernest Newboy walked out of shaggy green. “Yes, it is Tuesday, isn’t it.” He gestured with a rolled paper. “I just found out half an hour ago.” He did something on the inside of the latch plate. The gate clanked, swung in a little. “Glad to see you both.” He pulled it open the rest of the way.

“Isn’t the man who used to be a guard here anymore?” Lanya asked, stepping through. “He had to stay in there all the time.” She pointed to a small, green booth, out of sight of the sidewalk.

“Tony?” Mr. Newboy said. “Oh, he doesn’t go on till sometime late in the afternoon. But practically everybody’s out today. Roger decided to take them on a tour.”

“And you stayed for us?” Kidd asked. “You didn’t have to—”

“No, I just wasn’t up to it. I wouldn’t have gone anyway.”

“Tony…” Lanya mulled, looking at the weathered paint on the gate shed. “I thought his name was something Scandinavian.”

“Then it must be somebody else now,” Mr. Newboy said. He put his hands in his pockets. “Tony’s quite as Italian as you can get. He’s really very nice.”

“So was the other one,” Lanya said. “Things are always changing around here.”

“Yes, they are.”

They started up the path.

“There’s so many people in and out of here all the time I’ve given up trying to keep track. It’s very hectic. But you’ve picked a quiet day. Roger has taken everyone downtown to see the paper office.” Newboy smiled. “Except me. I always insist on sleeping late Tuesdays.”

“It’s nice to see the place again,” Lanya consented. “When will everybody be back?”

“I would imagine as soon as it gets dark. You said you’d stayed here before. Would you like to wait and say hello to Roger?”

“No,” Lanya said. “No. I was just curious.”

Mr. Newboy laughed. “I see.”

The gravel (chewing Kid’s callused foot) turned between two white-columned mock temples. The trees gave way to hedges; and what might have been an orchard further.

“Can we cut across the garden?”

“Of course. We’ll go to the side terrace. The coffee urn’s still hot I know, and I’ll see if I can find some tea cakes. Roger keeps telling me I have the run of the place, but I still feel a little strange prying into Mrs. Alt’s kitchen just like that—”

“Oh, that’s—” and “You don’t have—” Kidd and Lanya began together.

“No, I know where they are. And it’s time for my coffee break—that’s what you call it here?”

“You’ll love these!” Lanya exclaimed as they stepped through the high hedge. “Roger has the most beautiful flowers and—”

Brambles coiled the trellis. Dried tendrils curled on splintered lath. The ground was gouged up in black confusion here, and here, and there.

“—What in the world…” Lanya began. “What happened?”

Mr. Newboy looked puzzled. “I didn’t know anything had. It’s been like this since I’ve been here.”

“But it was full of flowers: those sun-colored orange things, like tigers. And irises. Lots of irises—”

Kidd’s foot cooled in moist ground.

“Really?” Newboy asked. “How long ago were you here?”

Lanya shrugged. “Weeks…three weeks, four?”

“How strange.” Mr. Newboy shook his head as they crossed the littered earth. “I’d always gotten the impression they’d been like this, for years…”

In a ten-foot dish of stone, leaves rotted in puddles.

Lanya’s head shook. “The fountain used to be going all the time. It had a Perseus, or a Hermes or something in it. Where did it get to?”

“Dear me,” Newboy squinted. “I think it’s in a pile of junk behind the secretary cottage. I saw something like that when I was wandering around. But I never knew it had anything to do with the fountain. I wonder who’s been around here long enough to know?”

“Why don’t you ask Mr. Calkins?” Kidd said.

“Oh, no. I don’t think I would do that.” Mr. Newboy looked at Lanya with bright complicity. “I don’t think I would do that at all.”

“No,” said Lanya, face fallen before the desolation, “I don’t think so.”

At the brim’s crack, the ground, oozy under thin grass, kept their prints like plaster.

They passed another vined fence; a deal of lawn, and, higher than the few full trees, the house. (On a rise off to one side was another house, only three floors. The secretary cottage?)

Set in the grass a verdigrised plate read:

MAY

From the five fat, stone towers—he sought a sixth for symmetry and failed to find it—it looked as though a modern building of dark wood, glass, and brick had been built around an old one of stone.

“How many people does he have here?” Kidd asked.

“I don’t really know,” Mr. Newboy said. They reached the terrace flags. “At least fifteen. Maybe twenty-five. The people he has for help, they’re always changing. I really don’t see how he gets anything done for looking after them. Unless Mrs. Alt does all that.” They climbed the concrete steps to the terrace.

“Wouldn’t you lose fifteen people in there?” Kidd asked.

The house, here, was glass: inside were maple wall panels, tall brass lamps, bronze statuary on small end tables between long couches covered in gold velvet, all wiped across with flakes of glare.

“Oh, you never feel the place is crowded.”

They passed another window-wall; Kidd could see two walls covered with books. Dark beams inside held up a balcony, flanked with chairs of gold and green brocade; silver candlesticks—one near, one far off in shadow—bloomed on white doilies floating on the mahogany river of a dining table. “Sometimes I’ve walked around thinking I was perfectly alone for an hour or so only to come across a party of ten in one of the other rooms. I suppose if the place had a full staff—” dried leaves shattered underfoot—“it wouldn’t be so lonely. Here we are.”

Wooden chairs with colored canvas webbing sat around the terrace. Beyond the balustrade the rocks were licked over with moss and topped by birches, maples, and, here and there, thick oaks.

“You sit down. I’ll be right back.”

Kidd sat—the chair was lower and deeper than he thought—and pulled his notebook into his lap. The glass doors swung behind New-boy. Kidd turned. “What are you looking at?”

“The November garden.” Arms crossed, Lanya leaned on the stone rail. “You can’t see the plaque from here. It’s on top of that rock.”

“What’s in the…November garden?”

She shrugged a “nothing.” “The first night I got here there was a party going on there: November, October, and December.”

“How many gardens does he have?”

“How many months are there?”

“What about the garden we first came through?”

“That one,” she glanced back, “doesn’t have a name.” She looked again at the rocks. “It was a marvelous party, with colored lights strung up. And a band: violins, flutes, and somebody playing a harp.”

“Where did he get violins here in Bellona?”

“He did. And people with lots and lots of gorgeous clothes.”

Kidd was going to say something about Phil.

Lanya turned. “If my dresses are still here, I know exactly where they’d be.”

Mr. Newboy pushed through the glass doors with a teawagon. Urn and cups rattled twice as the tires crossed the sill. The lower tray held dishes of pastry. “You caught Mrs. Alt right after a day of baking.”

“Hey,” Kidd said. “Those look good.”

“Help yourself.” He poured steaming coffee into blue porcelain. “Sugar, cream?”

Kidd shook his head; the cup warmed his knee. He bit. Cookie crumbs fell and rolled on his notebook.

Lanya, sitting on the wall and swinging her tennis shoes against the stone, munched a crisp cone filled with butter-cream.

“Now,” Mr. Newboy said. “Have you brought some poems?”

“Oh.” Kidd brushed crumbs away. “Yeah. But they’re handwritten. I don’t have any typewriter. I print them out neat, after I work on them.”

“I can probably decipher good fair copy.”

Kidd looked at the notebook, at Lanya, at Mr. Newboy, at the notebook. “Here.”

Mr. Newboy settled back in his seat and turned through pages. “Ah. I see your poems are all on the left.”

Kidd held his cup up. The coffee steamed his lips.

“So…” Mr. Newboy smiled into the book, and paused. “You have received that holy and spectacular wound which bleeds…well, poetry.” He turned another page, paused to look at it not quite long enough (in Kidd’s estimate) to read it. “But have you hunkered down close to it, sighted through the lips of it the juncture of your own humanity with that of the race?”

“Sir…?”

“Whether love or rage,” Mr. Newboy went on, not looking up, “or detachment impels the sighting, no matter. If you don’t do it, all your blood is spilled pointlessly…Ah, I suppose I am merely trying to reinvest with meaning what is inadequately referred to in art as Universality. It is an inadequate reference, you know.” He shook his head and turned another page. “There’s no reason why all art should appeal to all people. But every editor and entrepreneur, deep in his heart of hearts, is sure it does, wants it to, wishes it would. In the bar, you asked about publication?” He looked up, brightly.

“That’s right,” Kidd said with reserve and curiosity. He wished Newboy would go on, silently, to the poems.

“Publishers, editors, gallery owners, orchestra managers! What incredible parameters for the creative world. But it is a purgatorially instructive one to walk around in with such a wound as ours. Still, I don’t believe anybody ever enters it without having been given the magic Shield by someone.” Newboy’s eyes fell again, rose again, and caught Kidd’s. “Would you like it?”

“Huh? Yeah. What?”

“On one side,” intoned Newboy with twinkling gravity, “is inscribed: ‘Be true to yourself that you may be true to your work.’ On the other: ‘Be true to your work that you may be true to yourself.’” Once more Newboy’s eyes dropped to the page; his voice continued, preoccupied: “It is a little frightening to peer around the edge of your own and see so many others discarded and glittering about in that spiky landscape. Not to mention all those naked people doing all those strange things on the tops of their various hills, or down in their several dells, some of them—Lord, how many?—beyond doubt out of their minds! At the same time—” he turned another page—“nothing is quite as humbling, after a very little while, as realizing how close one has already come to dropping it a dozen times oneself, having been distracted—heavens, no!—not by wealth or fame, but by those endless structures of logic and necessity that go so tediously on before they reach the inevitable flaw that causes their joints to shatter and allow you passage. One picks one’s way about through the glass and aluminum doors, the receptionists’ smiles, the lunches with too much alcohol, the openings with more, the mobs of people desperately trying to define good taste in such loud voices one can hardly hear oneself giggle, while the shebang is lit by flashes and flares through the paint-stained window, glimmers under the police-locked door, or, if one is taking a rare walk outside that day, by a light suffusing the whole sky, complex as the northern aurora. At any rate, they make every object from axletrees to zarfs and finjons cast the most astonishing shadows.” Mr. Newboy glanced up again. “Perhaps you’ve followed some dozen such lights to their source?” He held the page between his fingers. “Admit it—since we are talking as equals—most of the time there simply wasn’t anything there. Though to your journal—” he let the page fall back to what he’d been perusing before—“or in a letter to a friend you feel will take care to preserve it, you will also admit the whole experience was rather marvelous and filled you with inadmissible longings that you would be more than a little curious to see settle down and, after all, admiss. Sometimes you simply found a plaque which read, ‘Here Mozart met da Ponte,’ or ‘Rodin slept here.’ Three or four times you discovered a strange group heatedly discussing something that happened on that very spot a very long time by, which, they assure you, you would have thoroughly enjoyed had you not arrived too late. If you can bear them, if you can listen, if you can learn why they are still there, you will have gained something quite valuable. ‘For God’s sakes, put down that thing in your hand and stay a while!’ It’s a terribly tempting invitation. So polite themselves, they are the only people who seem willing to make allowances for your natural barbarousness. And once or twice, if you were lucky, you found a quiet, elderly man who, when you mumbled something about dinner for him and his slightly dubious friend, astounded you by saying, ‘Thank you very much; we’d be delighted.’ Or an old woman watching the baseball game on her television, who, when you brought her flowers on her birthday, smiled through the chain on the door and explained, ‘That’s very sweet of you boys, but I just don’t see anyone now, anymore, ever.’ Oh, that thing in your hand. You do still have it, don’t you?”