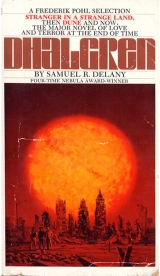

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 44 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“Don’t press too hard,” she said. “I don’t want to injure the material. No, no…I’m not driving you away!”

“I think you look nice,” Denny said. “I think…” He whispered in her ear.

“Young man!” Lanya said. “I don’t believe I know you—”

“Aw,” Denny said, “go suck on my dick…” and started away.

“Hey, I was kidding…” Lanya called, amused puzzlement at Denny in her voice. Her waist tugged in Kid’s arm.

Denny turned, his face flickering in the passing lights. As they caught up to him, he grinned. “I wasn’t.” He put his arm around her too.

They stepped up on the next corner, watching the jogging luminosities, delicate or bulbous, pass beneath charred branches, under lampposts suspending inverted crowns of broken glass, by houses with columned porches, entrances gaping on blackness, as if the occupants had rushed out to see, then fled back in too distracted a state to close the doors behind.

Blocks later that image, still working in Kid’s mind, finally loosened a chuckle which rolled around in his mouth.

Lanya and Denny were looking at him, she with a smile anticipating explanation, he merely without comprehension. Kid pulled her tighter. Denny’s fringe brushed his arm, then crushed against him as he lowered his own arm down her back. Her far hip, moving under Kid’s fingers, did not change its rhythm.

“This is all very colorful.” Madame Brown strained back on the leash. “But it’s quite a walk. Muriel, heel!”

“Roger’s friends are pretty colorful too,” Lanya said. “He’ll rise to the occasion.”

Vines climbed the wall. Willow boughs hung over it, sawtooth shadows growing and shrinking as the red, orange, and green lights passed.

“We’re just about there, ain’t we?” Nightmare called from the middle of the street. Insects and arthropods floated around him, laughing gigantically.

“Yeah!” Kid called. “The gate’s up there.”

Denny was fingering in his shirt pocket. “Now what am I supposed to do with this thing?”

“Once we get inside,” Lanya explained, “just turn me on. Every once in a while, give a look and if what you see is too dull, fiddle with those knobs till something interesting happens. Tak says its range is fifty yards, so don’t get too far away. Otherwise I go out.”

Suddenly Kid pulled away to shoulder through the bright, boisterous crowd. On a whim’s stutter, he thumbed his shield’s pip: it clicked.

From the inside, he remembered, your shield is invisible. But people had cleared around him. (I don’t know what I am.) He looked down at the cracked pavement. (But whatever it is, it’s blue.) The halo moved with him across the concrete.

Three beside him turned off their lights, growing shadows before them from the lights behind.

It’s like a game (there were the stone newels), not knowing who, or what, you are. He wondered how long before he would finally get someone aside and ask. And flipped his pip to kill the temptation.

Stepping ahead of the crowd, he grabbed the bars. The others massed loudly around. He wondered, as he stared in at the pines, lit clumsily and shiftingly by his bright entourage, what to call out.

“Hello!” A young—Filipino? (probably)—in a green turtleneck and sports jacket stepped up. “You’re the Kid? I thought so. I’m Barry Lansang. I’m on the gate tonight. Just a second, I’ll let you all in.”

“Hey, we’re here!”

“How we gonna get in?”

“Shut up! He’s lettin’ us in now.”

“This here’s where we going?”

Lansang stepped aside. The gate went Clang, and the noise level around Kid cut by two-thirds.

Lansang swung back the bars.

Kid stepped forward, aware that the others had not.

“Go on up,” Lansang smiled. “They’re all expecting you. Is this your whole party?”

“Yeah. I think so.”

“If you expect anybody else to come by later, just leave their names with me and I’ll make a note.”

“Naw. This is it.”

Lansang smiled again. “Well, if stragglers come along later and we do have an identification problem, I can always go up and find you. Come on in,” this last over Kid’s shoulder, accompanied by a gesture.

Kid looked back.

The gateway crowded with silent, familiar faces.

“Come on,” Kid said.

Then they came.

Dragon Lady was among the first. “This is something, huh?”

“Yeah,” Kid said. “And this is just the trees.”

“Follow the driveway up,” Lansang instructed. He was, Kid saw, enjoying himself.

Lanya joined Kid; her gown blushed pink. As they walked together, robins-egg droplets grew into puddles which swelled to oceans.

“Am I doing this right?” Denny reached under his vest into his shirt pocket with a black and glittering arm.

Lanya looked down at herself. “I think the other knob—the one on the front—is for the color intensity. Leave it like this for now. We don’t want to shoot it all on the entrance.”

Floodlights between the huge pines lit the gravel and, after the night journey, made them squint.

“Here we are,” Madame Brown said, looking off between two trees where one light was not working. “All safe and sound.”

Muriel walked close to her.

“Where’s everybody likely to be?” Kid asked Lanya, whose dress dribbled a metallic green across her left breast.

“Out on the terrace gardens. Where we were that afternoon with Mr. Newboy.”

Kid did not remember the driveway as this long. “How come they have all this electricity?”

“When it’s all working, they can get this whole grounds practically bright as day,” Lanya said.

They passed the last trees:

The house was bright as day against the night.

“Newboy said something about lanterns…”

“It doesn’t all work inside,” Lanya said. “There was one whole wing where there wasn’t a socket functioning.” (Some dozens of men and women along the stone terrace turned to look.) “But whenever Roger lights the whole place up like this, I get the feeling I’m watching some really banal Son et lumiere.”

The scorpions quieted as they saw the other guests.

Suit, shirt, and tie of different blues, one pushed from among them. Short blond hair, a serious expression, he was followed by two women—the older also in blue, hair rinsed the same shade as his shirt. The younger, in a floor-length brocade, looked unhappy.

Calkins, Kid thought starting forward. But anticipation had betrayed him: It was Captain Kamp.

“Kid—!” called out affably enough—“you got here. And these are your friends…I…um. Well, we’ve had a little…” Initial affability spent, Kamp looked confused. “Now, Roger hasn’t gotten back yet. He told us he might be late, and to tell you how sorry he was…He asked me and Thelma—” he nodded at the woman in brocade—“and Ernestine—” and at the woman in blue—“to say hello for him when you got here…um, since I’d met you—” his eyes kept moving to the people behind Kid—“to introduce you around and things. Now, Ernestine, this is the Kid. And this is Thelma…”

Ernestine, who seemed much less nervous than Kamp, said, “I’m Ernestine Throckmorton. How wonderful to have all you young people here. Hi, love,” which was a special nod to Lanya, who grinned back. “Now I think the only thing to do is plunge in and go over how everything is laid out. Why don’t you all come with us and we’ll show you where to get something to eat and drink…? Come on, now.” She turned and motioned them up the steps onto the terrace.

As the other guests stepped back, staring, she went for the two nearest and brightest scorpions. “And what are your names?”

“Nightmare,” Nightmare said rather like a question.

“And your friend?”

“Oh, yeah. I’m sorry. This here is Dragon Lady.”

“Very pleased to meet you both. You know, I’ve heard your names before; well, read them actually, in the paper. Really, I’m quite terrified.”

Kid glanced over.

Ernestine, who did not look terrified one bit, strolled by the staring (some smiled) guests, Nightmare on one arm, Dragon Lady on the other.

“Bill!” she cried out. (Bill was smiling.) “Come here, dear.”

Bill, a tall, handsome man, perhaps thirty-eight, in a black turtle-neck, a can of beer in one hand (the only guest there already, without a jacket), fell in beside them. “Bill, this is Nightmare and Dragon Lady. You mentioned them in that article you did for Roger a little while ago. Now, have you ever met them?”

“I’m afraid I haven’t.”

“Well, here they are.”

“Hello,” and “Hello,” Nightmare and Dragon Lady said, just out of sync.

“I’m glad to meet you, but I’m not sure that you’re glad to meet me after some of the things I said.”

“You wrote an article?” Nightmare asked. “In the paper?”

“I didn’t read no article,” Dragon Lady said.

“Probably all just as well, considering some of what I put down—here, we’re all heading for the beer wagon down at the end—” Bill gestured with his can. “I’m really surprised to meet you here with the Kid. I was under the impression that the various gangs—nests—kept at each other’s throats.”

“Naw,” Nightmare said. “Naw, it ain’t like that…”

While Nightmare explained how it was, Kid looked over again. Bill had replaced Ernestine, who had drifted back to other scorpions: “I’m Ernestine Throckmorton. And you’re…?”

Lanya smiled and whispered: “This is going to be work.” Concern underlay the smile.

“Huh?”

“Since Roger’s not here. To get people mixing. I mean if he’s got one, that’s his single overwhelming talent. Ernestine’s competent. I’ve seen her work before—”

“I guess you know her.”

“I recognize about five people here, I think. Thank God. Roger usually keeps a pretty inspired group. Ernestine can even be brilliant. Roger, however, has genius. And I’m afraid I was sort of counting on it this evening. Don’t be mad if I abandon you for a little while. You can take care of yourself. Why don’t you start by introducing me to the Captain?”

“Oh,” Kid said. “Sure. I know him. Glass and I walked him up here one night.”

“Glass…” she considered, and her consideration made him pause till she nodded:

“Captain Kamp?” he had to say three times before the Captain turned. “This is my friend, Lanya Colson.”

“Since everyone’s talking to people they’ve read about in the papers,” Lanya said, “I guess I can tell you that I’ve read about you.”

“Um…” The Captain smiled uncertainly.

“I spent some time here with Roger a little while ago,” Lanya said, which to Kid sounded pretty phony.

But the Captain’s “Oh?” was filled with relief.

She seemed to know what she was doing.

“Where has Roger gone? It’s not like him to arrange something like this and then not be here.”

“Now I’m sure he’ll be back,” the Captain said. “I’m just sure. He had it all arranged with the lady in the kitchen—”

“Mrs. Alt?”

“—yes. And she’s really laid out a nice spread. I don’t know where he went off to. I was sort of hoping he’d be back in time. Partying isn’t really my strong point. And I didn’t realize all of you people were going to come. Of course, Roger did say bring twenty or thirty friends, didn’t he? But. Now. Well…”

The long terrace ended at a patio.

Two tables were set up on the stone flags.

Flame blued the copper bottoms of a half-dozen chafing dishes.

There were paper plates. There were plastic forks. The napkins were linen.

Most of the guests, before on the terrace, had now drifted with them to the patio.

“You just help yourselves to anything you’d like to eat.” Ernestine’s arms rose like a conductor’s. “That’s the bar over there. Either of these gentlemen—” one young black bartender, one elderly white one, both in double-breasted blue– “will get you a drink. Those two kegs over there are beer. If you want it in the can, the cooler, here—” she thumbed at it; two people laughed—“is chock-full.” In more modulated tones to whoever happened to be beside her: “Would you like something to eat?”

“Sure.” Revelation said.

“Yes, ma’am,” from Spider.

No full meal had been cooked in the nest that day.

“Captain Kamp,” Lanya was saying, “this is Glass. Glass, this is Captain Kamp.”

“Oh, yes. We’ve met, now.”

“You have?” Lanya’s surprise sounded perfectly delighted and perfectly sincere. (If I wrote her words down, Kid thought, what she’s saying would vanish into something meaningless as the literal record of the sounds June or George makes.) “Then I can leave the two of you alone and get something to eat,” and turned away.

(“Now,” Kamp said. “Well. What have you been doing since I saw you last?”

(Glass said: “Nothing. You been doing anything?”

(Kamp said: “No, not really”)

Lanya shouldered through Tarzan-and-the apes. “Hey, come on with me, I want you to meet someone. No, really, come on,” and emerged with Jack the Ripper and Raven, herding before them the diminutive black Angel. “Dr. Wellman, you’re from Chicago! I’d like you to meet Angel, the Ripper, and Raven.” She stayed a little longer with them. Kid listened to the conversation start, halt, and finally settle into even exchanges (between Angel and Dr. Wellman at any rate) about community centers in Chicago, which Angel seemed to think were “all right, man. Yeah I really liked that,” while Dr. Wellman held out, affably, that “they weren’t very well organized. At least not the ones we did our reports on.”

“Hey, Kid.”

Kid turned.

Paul Fenster bobbed a paper plate at him.

“Oh, hi…!” Kid grinned, astonished how happy he was to see someone he knew.

“Get yourself something to eat, why don’t you?” Fenster said and stepped away between two others, while Kid held the words he’d been about to say clumsily in his mouth.

He wished that Tak had come. And that Fenster had not.

Lanya passed close enough to smile at him. And he was close enough to hear her coax Madame Brown: “Work, work, work!” in a whisper.

Wrapping herself in her leash, Madame Brown turned and said: “Siam, this is a terribly good friend of mine, Everett Forest. Siam was my patient, Everett.”

Everett was the man Kid usually saw at Teddy’s in purple angora. Tonight he wore a navy blazer and grey knitted pants.

Somewhere across the patio, Lanya was holding paper plates in both hands, about to give them away. Turquoise billowed about her silver hem, trying and failing to rise like a lazy lava lamp. He started to go take a plate, but suddenly thought of Denny, looked around for him—

“I asked Roger if I could be on—”

Kid turned.

“—on your welcoming committee—” (unhappy Thelma of the floor-length brocade)—“because I didn’t think I could possibly get to speak to you otherwise. I wanted to tell you how much pleasure Brass Orchids gave me. Only now I—find that it’s—” her dark eyes, still unhappy, fell and rose—“just very difficult to do.”

“I’m…thank you,” Kid offered.

“It’s hard to compliment a poet. If you say his work seems skillful, he turns around and explains that all he’s interested in is vigor and spontaneity. If you say the work has life and immediacy, it turns out he was basically concerned with overcoming some technical problem.” She sighed. “I really enjoyed them. And outside a few polite phrases, there just isn’t the vocabulary to describe that sort of enjoyment in a way that sounds real.” She paused. “And your poems are one of the realest things that’s happened to me in a long time.”

“Damn!” Kid said. “Thank you!”

“Would you like something to drink?” she suggested in the silence.

“Yeah. Sure. Let’s get something to drink.”

They walked to the table.

“I’ve written—and published—two novels,” Thelma went on. “Nothing you’re likely to have heard of. But the effect of your poems on me, especially the first four, the Elegy, and the last two before the long conversational one in meter, is rather the effect I’d always hoped my books would have on people.” She actually laughed. “In a way, your book was discouraging, because watching your poems gain that effect showed me some of the reasons why my prose often doesn’t. That condensed and clear descriptive insight is something I envy you. And you wield it as naturally as speech, turning it on this and that and the other…” She shook her head, she smiled. “All I can do is find a lot of adjectives that you’ve got to fill up with meaning for yourself: Beautiful, perhaps marvelous, or wonderful…”

Kid decided they all applied, to her anyway; his delight was awesome. But holding it (the black bartender poured him a bourbon) was an entrancing irritation as pleasurable in building as a sneeze in relief.

Denny stepped up to the table, fingering inside his shirt pocket. “Hey, you wanna see something?”

Kid and Thelma watched.

And across the patio, Lanya’s dress splashed around with orange and gold. The people she was talking with stepped back in surprise. She looked down at herself, laughed, searched about till she saw Kid and Denny, and blew them a kiss.

Thelma smiled and did not seem to understand.

Kid introduced Thelma to Denny. She introduced them to someone else. Bill, the reporter, joined them. Thelma left. Kid watched laddering relational torques and tensions, already interpreting them as likes, dislikes, ease and unease. Lanya brought Budgie Goldstein to meet him. Budgie, immense in green chiffon, explained how frightened she’d always been of scorpions but now how nice they all seemed, punctuating her explanation with sharp, short laughs. They had wandered from the terrace onto the—

“These? I believe these are…Toby, what are these?”

“The September Gardens, Roxanne. September, remember…And who is this young man? You wouldn’t be the Kid?”

And he was handed on.

He liked it.

It took half an hour to realize he had been kept entirely away from the other scorpions.

Besides what he estimated at two dozen house guests, there were another thirty-odd invited from town, including Paul Fenster, Everett (Angora) Forest, and (Kid was surprised to see him leaning over against the stone wall, talking with Revelation) Frank.

There was a bridge between January and June.

Kid looked over the rail at wet rock; floodlights glistened on a vein of clotted leaves—there was no clear water. Lanya and Ernestine passed on the little path underneath.

Ernestine said into her drink: “The only thing I could think of to do was to physically push them at one another…”

Kid thought Lanya had not seen him, but a moment after she vanished she said, “Hello,” behind him.

He turned from the rail. “You’ve been very busy.”

Wrist against forehead, she mimed distress. “Phase one, at any rate, is over. Just about everyone knows now it’s possible to talk to everyone else. Are you having a good time?”

“Yeah. They’re all here for me.” Then he grinned. “But they’re all talking about you.”

“Huh?”

“Three people have told me how great your dress is,” which was true. “Denny’s doing a good job.”

“You’re a doll!” She clapped his cheeks between her palms and kissed him on the nose.

Cathedral, California, and Thruppence ambled below them on the path, light and dark shoulders together. I feel responsible for them, he thought, recalling her initial efforts. He laughed.

Her dress began to broil with green and lavender.

She saw and asked, “Where’s Denny gotten off to? Let’s go look for him.”

They did and could not find him, spoke to others, and then Kid lost her again.

From the high rocks of—“October,” said the plaque on the rust-ringed birdbath—he looked down toward the terrace.

Two women he had not met, with Bill (whom he had) between them, had cornered Baby and were talking at him intently. Baby smiled very hard, his paper plate just under his chin. Sometimes he dropped his head to nod, sometimes to scrape up another and another forkful. Once in a while someone across the terrace, when they were sure they were unobserved, would glance—two ladies, one after another, maneuvered for the better view, noticed they were observed, and walked away.

Someone was in the bushes behind him.

Kid looked around: Jack the Ripper backed out; from the movement of his elbows, he was closing his fly. He turned. “Huh?…oh, it’s just you, man.” He grinned, bent, adjusted himself. “Scared somebody gonna see me back there takin’ a leak.”

“There’s a bathroom in the house somewhere.”

“Shit. I didn’t wanna go askin’ around for that. My piss ain’t gonna kill no flowers. This is a real nice place, huh. A real nice party. Everybody’s real nice. You havin’ a nice time? I sure am.”

Kid nodded. “You catch Baby when he came in?”

“No,” the Ripper drawled with a wildly interrogative cadence.

“You said you wanted to see what the reaction was. I missed it. I was wondering if you caught it.”

“God damn!” The Ripper snapped his fingers. “You know I wasn’t even looking?”

“There he is.”

“Where?”

Kid nodded toward the terrace.

The Ripper stuck his hands in the back of his pants. “What they talkin’ about?”

Kid shrugged.

“Hey, man!” The Ripper’s hands came loose again. “I gotta go down and hear this.” He grinned at Kid who started to say something. But the Ripper was off along the rocks.

At the four-foot terrace wall, the Ripper straight-armed up, scrambled over—half a dozen looked—and jumped. A bopping lope took him to the bar. The white bartender gave him two drinks. He came to the corner, thrust one glass at Baby and said loud enough for Kid to hear: “Now I know you want a drink, Baby, ’cause you gonna need something to keep you warm.”

Several people laughed.

Baby took the drink in both hands—he had put his plate down on the wall—and looked as though he were about to dive into it. But Bill and the two women merely made room, and continued.

Seconds later, the Ripper, all weight on one leg, heavy lower lip sucked in and long head quizzically cocked, stood rapt, nodding in unison with Baby.

Curious at their low converse, Kid walked away from it into March.

Only one light worked here, anchored high and harsh on an elm. Captain Kamp stood silhouetted at the vertex of his shadow. “Hello, now, I was just coming back this way…you enjoying yourself?” Backlight made him ominous; his voice was cheerful. “I was just over there taking a—” (Kid expected him to say “leak”)—“look in the August gardens. There’re no lights in there, so I guess people are staying clear. But you can see down into the city. A few street lights are still on. I’m not too good at this ersatz host business. And this party takes some hosting.” Kamp stepped up. Kid turned to walk with him. “Now I sure wish Roger would get here.”

“Doesn’t look like anyone’s missed him too much.”

“I have. I’m just not used to all this…well, sort of thing. I mean, trying to be in charge of it.”

“I guess I’d like to meet him.”

“Sure. Of course you would.” Kamp nodded as they came nearer the house. “I mean he’s giving this party for you, for your book. You’d think he’d…but now I’m pretty sure he’ll get here. You don’t worry now.”

“I’m not and don’t mean to start.”

“You know I was thinking—” they walked up the stone steps—“about some of the things we were talking about when I first met you.”

“That was a strange evening. But it came after a strange day.”

“Sure did. Have you seen Roger’s observatory?” Kamp interrupted himself. “Perhaps you’d like to go up and see it.”

Kid was curious at the transition rather than the suggestion. “Okay.”

Coming down the terrace, Lady of Spain, Spider, Angel, Raven and Tarzan, circled gangling D-t:

“D-t, man, you gotta see this!”

“I ain’t never seen no garden like this before. All them flowers—”

“—and a big fountain that works and all.”

“Come on. We gonna show you.” Lady of Spain tugged his arm.

“D-t, you ain’t never seen no garden as pretty as this in your whole life!”

“I guess—” Kamp opened the door for Kid—“I’m just not used to it. I mean all these different…kinds of people. Like that boy back there walking around with no clothes on? And everybody going on just like there was nothing wrong.” The large, dark room was lined with books. In candlelight some dozen people sat on the floor or on hassocks. Several looked up from a tape recorder from which organ music flowed. One man (Kid remembered his making some joke in November about the smoke) said, “Kid? Captain? Would you like to join us? We were just listening to some—”

“We’re going to the observatory.” Kamp opened another door.

The organ piece ended; after a slight pause, a long note bent. Then another…They were playing “Diffraction.”

Kid smiled as he walked after Kamp down a hall nearly black. He could hear Lanya’s whistle. At the top of a stairway Kid saw faint light. The carpeting was thick and so warm under his bare foot he wondered if there were heating on.

“I suppose it wouldn’t be so bad if Roger was here. But being left in charge of a party for a bunch of people that, frankly, I’d put out of my house…”

Kid was quietly amazed and wondered what Kamp was thinking in the pause.

“…I just don’t know what to do. Do you know what I mean?”

Anything, Kid thought, I say will sound angry and stupid. He said, “Sure,” and followed Kamp up the stairs.

“A few months ago,” Kamp said, “I was in some experiments. They didn’t have anything to do with the moon. In fact I had to get a special release from the Space Program to participate. Some students of a friend of mine at Michigan were running tests, and I guess he thought it would be a feather in his cap to get me for a guinea pig. Now, it’d been so long since I had anything to do that wasn’t in some way connected with the Program, I went along with it. They were experiments on sensory deprivation and overload.” At the head of the steps, Kamp waited for Kid before starting up a third flight.

He led Kid across a brick floor to a double doorway.

“I was in the overload part. It was all pretty amateurish, actually.”

Kid stepped onto what first seemed a semi-circular balcony.

Faintly, below, a room full of people began to clap in time to the music—

“I guess they’d all been reading too many articles on LSD—”

–and shouted.

“—I took LSD back in the late fifties—more tests, that this psychiatrist friend of mine was running. But I’ve always been a little ahead of what’s going on. Anyway, I know what it’s like, LSD. And I’m pretty sure most of those kids setting up those experiments in Michigan didn’t.”

The terrace was enclosed in a glass dome. In the center was a six-foot in diameter celestial globe of clear plastic. Light from the garden below struggled in the smoke above, glowing like dilute milk.

“Now I guess you’ve taken LSD and all that stuff.”

“Sure.”

“Well, all they’d been doing was looking at all the pretty pictures everyone had been drawing.” Kamp touched the globe, removed his fingers. Aries passed across Libra. The stars were glittering stones set in the etched constellations. “They had spherical rear-projection rooms, practically as big as this place here. They could cover it with colors and shapes and flashes. They put earphones on me and blasted in beeps and clicks and oscillating frequencies. Anyway, I was supposed to pick out patterns from all this. Later I learned that mine was the control group: We were given no patterns at all. I was told all the ones I had seen I had imposed myself…But after two hours of testing, two hours of fillips and curlicues of light and noise, when I went outside, into the real world, I was just astounded at how…rich and complicated everything suddenly looked and sounded: The textures of concrete, tree bark, grass, the shadings from sky to cloud. But rich in comparison to the sensory-overload chamber. Rich…and I suddenly realized what the kids had been calling a sensory overload was really information-deprivation. It’s the pattern that colors and shapes assume that tell you whether it’s a cow or a car you’re looking at. It’s the very finest alternations in color differentiation over a surface that tell you whether it’s maple or pine, styrene or polyethylene, linen or flannel. Take any view in front of you and cut off the top and bottom till you’ve only got an inch-wide strip and you’ll still be amazed at all the information you can get from just running your eye along that. Well, all this started me thinking back to the moon. Because that had been a place—and it happened in every mile en route—where standard information patterns just broke down. And yet, that’s something we haven’t been able to talk about—to anyone—since we got back. We’d trained for prolonged free-fall by spending time underwater in diving suits. I remember when we actually hit sustained weightlessness, I broadcast back, ‘Hey, it’s just like being underwater!’ and yet as I said that into the chin mike, I was thinking: You certainly could never mistake the two conditions for one another. But I couldn’t think of any way to say what was different about it, so I just described it the way everybody, who’d never been there themselves, had told me it was going to feel like. Later I thought, that’s like telling someone the world is flat and sending him off to the edge; but because he doesn’t know quite how to describe such gentle roundness, he mumbles and stammers and says, ‘Well yeah, I was at the…edge.’ And the thing about the moon itself, the one thing I’ve really never told anybody, because I don’t think I would have known how before those experiments: it’s another world, and when you’re there, you have no way of knowing what anything means. Physically. That whole landscape tells you nothing about itself, on any level, in the way that the most desolate stretch of sand on earth tells you about winds that have blown over it, rains that have or have not fallen, or the feel it might have beneath your feet if you walked across it. ‘An airless, waterless void…’ the way they say in all the science-fiction stories? No, that refers to some desert on earth, or what space between the stars looks like when you’re safely tucked under the atmosphere. The moon is a different world, with a different order that you don’t understand. There isn’t that richness—not because it isn’t in bright colors, or because it’s all brown, purple, and grey. It’s because you run your eyes over the rocks and dirt, you have no way to know what the tiny alterations in color mean. Even though it has a horizon and perspective, and…well, rocks and dirt, it’s more like being in that sensory-overload chamber than anything else. And of course, it isn’t like that at all. It wasn’t horrible. Horror still has something to do with Earth. I suppose it was frightening. But even that was absorbed in the excitement of it. I—” he paused—“do not know how to tell you about it.” He smiled and shrugged. “And that’s probably the one thing I really haven’t told anybody before. Oh, I’ve said, ‘You can’t describe it. You’d have to be there.’ But that’s my first wife telling her mother-in-law about the time we went to Persia. And that isn’t what I mean.”