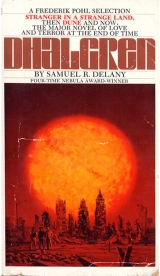

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 57 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“To the Richards’ home. What about yours?”

“You were going to tell me what you thought about the Kid. Maybe you’ll tromp on something and I’ll twitch for you.”

“All right. I think…”

I looked at her leg.

“…you are very disturbed. You are personable, intelligent, forceful, vital, talented. But your basic ego structure is about as stable as a cracked teacup. You say you’ve lost bits and pieces of yourself? I think that’s exactly what’s happened. The point is, Kid, we still don’t treat the mentally ill as though they were just sick. We treat them as though they were some strange combination of unclean, depraved, and evil. You know, the first mental hospitals in Europe were leprosaria, deserted all over the continent at the end of the middle ages because—for some reason we still don’t know—there was a spontaneous remission in the disease over about seventy-five years, though it had been endemic for the last three thousand. Was it rising hygiene standards? A mutation in the germ? The point is that till then, though they had occasionally been shipped about on local rivers, the insane had never been hospitalized before. But when they were suddenly confined in these immense, empty buildings that, in some cases for hundreds of years, had held lepers, they took on as well the burden of three thousand years of superstition and fear connected with that unfortunate disease. And a good argument can be made that that’s still more or less how we regard you today—complete with religious connotations. Mental illness is still seen as a scourge of the Lord. Freud and his offspring turned it into a much more sophisticated scourge. But even for him it is essentially a state of distress resulting from how you have lived your life and how your parents have lived theirs. And that is biblical leprosy, not the common cold. Tell me, what would you say to the idea that all your problems—the hallucinations, the depressions, even the moments of ecstasy—were biogenic? That the lapses of memory are an RNA depletion in the lower cortex; that the sudden fears are adrenal disruptions caused by random pituitary spasms; that the unreality that plagues you is merely a pineal cyst, inhibiting the production of serotonin?”

I looked up on the moonscape where there were no trees.

“That’s sure as hell what it feels like,” I said.

“Then, you differ from the businessmen, in that they are usually rather reluctant to give up any of the extrabiological significance of their symptoms. The over-determined human mind would rather have everything relevant, even if the relevance is simple-minded.”

“When I was in the hospital—” remembering, I smiled—“I used to have a friend who’d say: ‘When you’re paranoid, everything makes sense.’ But that’s not quite it. It’s that all sorts of things you know don’t relate suddenly have the air of things that do. Everything you look at seems just an inch away from its place in a perfectly clear pattern.” Once more I looked at her leg. “Only you never know which inch to move…” I felt my face wrinkling over my skull with concentration.

She said: “Your dream. Can you think why you particularly wanted to tell me about it?”

I looked at my lap; “I don’t know. I’ve just had it on my mind a long time.”

“You mean it isn’t a recent dream?”

“Oh, no. I had it…I don’t remember when; while I was still staying in the…park?”

“And it isn’t a recurrent dream?”

“No. I only had it once. But it…I just keep thinking about it.”

One hand at her necklace, she fingered a lens. “I asked you this before, but I want to check: In the dream, you made love, had an orgasm, and then went to the cave. It wasn’t just a heavy necking session?”

“No. She came first. I remember it surprised me, because I was just about ready myself. I finished up about thirty seconds after she did—which is unusual with me. Usually it takes me a couple of minutes longer. When I shot my load, leaves blew against my side. And I opened my eyes and we talked for a while.”

Madame Brown mulled, a glass bead pressed to her chin. “I was on a research team that did a study some years ago—dirty old lady that I am—about sex dreams. We had, admittedly, a small sampling—two hundred and thirty-nine; they’d all checked yes to the question: whether they felt they had satisfactory sexual outlets. We had men, women, a few late adolescents; some homosexuals, of both sexes. One overwhelmingly consistent pattern was that when sex, in a dream, led to actual orgasm, either the dream ended or the subject awoke. Of course there was nothing conclusive about the study, and I can make a list of biasing factors an ell long. But yours is the first dream I’ve ever encountered, during or since the study, where orgasm was achieved and the dream continued.” She looked at me like she was waiting for a confession.

“What am I supposed to say?”

“Anything that comes to mind.”

“You think I didn’t have the dream? You think I’m lying, or that maybe the dream was…” I hunched my shoulders and felt silly. “I don’t know…”

“You want me to suggest it wasn’t a dream? That it was real?” She gave a sudden, small frown. “Yes, you do, don’t you? Well, I can understand that—if it seemed real to you.” Underlying her frown was a slight and slightly sad smile. “But it was a dream, Kid. Because…” She paused; and I wondered what moons and suns returned to devil her memory. “Well, let’s assume it wasn’t. Would you like to discuss it further? What’s the first thing that comes to mind?”

“I’m frightened, all of a sudden,” I said. “Again.”

“Of what?”

“Of you.” I tried a smile and felt it abort deep in the muscles of my face.

“What about me frightens you?”

I looked at her scarred leg. I looked at the bead she rubbed against her chin. (I remembered what she had said, when I first met her, about them; I remembered what Nightmare had said. What Nightmare had said made more sense. But I want to believe her. Doesn’t that count for something?) “I don’t…I can’t…” I began to cry again. And I couldn’t stop this time. At all. “It’s got to be a dream! It’s got to…” Could she hear it for my sobbing? “If it isn’t a dream, then I…I’m crazy!” And I cried about all the things people can not understand when other people say them. I cried over the miracle that they could understand anything at all. I cried for all the things I had said to other people that had been misunderstood because I, not knowing, had said them wrong. I cried with joy about those times when someone and I had nodded together, grinning over an understanding, real or wished for. A couple of times I managed to choke out; “I’m so frightened…I’m so frightened! I’m so alone!” I pushed my fingers into my mouth to stop the sound, rocking forward and back, bit on them, and couldn’t stop.

Madame Brown brought me Kleenex. I blubbered, “Thank you,” too inarticulate to be understood, and cried in despair that I could not even make that clear. I wandered back far enough in the cave to think, “This has got to be good for something,” but climbed up the rocks where she told me to go, in the orange flicker, and didn’t find anything there, so got scared again and cried and rocked in my seat, the pits above my kneecaps hurting, which is the place that hurts when I want to fuck bad, and kept crying and biting the sides of my hands for what seemed hours but was probably only fifteen, twenty minutes.

Denny’s circumcised; I’m not. After we all made it this afternoon, he sat wedged in the loft corner and kept asking Lanya which kind of dick she liked more: “…one that’s still got curtains or one that’s been cut?”

“It doesn’t make any difference to me.” She sat cross-legged with my feet in her lap, playing with my toes.

“But which do you think is sexier?”

“I don’t think it matters. They both feel the same.”

“But don’t you think one looks better?”

“No. I don’t.”

“But they are different; so you have to feel different about them. Which one…?” and on and on till I got bored lying there listening.

To stop it, I asked him: “Look, which one do you like more?”

“Oh. Well, I guess…” He leaned forward, hunching his shoulders. “The one that’s still got it all there…like yours, is better.”

“Oh,” Lanya said, with a puzzled look as though she’d suddenly understood something. About him.

“Yeah.” Denny grinned, came out of his corner, and lay down with his head on my lap.

Lanya nodded, swung out from under my legs, and lay down with her head on Denny’s lap. I put my feet in hers.

And it lessened; I felt weaker, better, and when I quieted, Madame Brown said: “You know, you asked me what I think of you? On the strength of the amnesia, the anxiety attacks, yes, that alone would make me suggest, if we were someplace else, that you go into a hospital. But as you say, there aren’t any mental hospitals in Bellona any-more. And, frankly, I don’t know quite what they’d do for you if you went. It might take some of the pressure off you of being ‘the Kid.’ Perhaps that would allow some things to heal that are wounded, some things to settle in place that are swollen.”

I nodded as though I was considering what she said—which wasn’t what I was doing at all. “Do you…” I asked. “Do you believe…in my dream?”

“Pardon me?”

“Do you believe I had that dream?”

She looked confused. “I’m not sure what you mean. But…don’t you?”

“Yes,” I said. “Oh, Jesus Christ I do! I…I believe it was a…I had that dream.” And realized there was a whole well of anguish from which only a single cup had been dipped. She hadn’t understood. But that was all right.

Over her face was a mask of compassion: “Kid, there was nothing in the study to say that it couldn’t happen the way you said. You remember it very clearly, and told all the details. Yes, I believe it was a dream. I don’t know whether or not you do, but it’s probably not a bad idea for you to keep trying.”

Over mine was a mask of relief: “Madame Brown,” I said, “I am not going back into a mental hospital. The place I was in, for a leprosarium, was pretty nice. But I think I’d have to be crazy to go into one again. And you can read that any way you want!”

That made her laugh. “Though, in Bellona, the problem would be if you wanted to go in a hospital.” Suddenly she cocked her head the other way. “Do you know why I offered you that job with the Richards, the morning I met you in the park?”

“You said it had something to do with—” I put two fingers on the optic chain across my chest—“these.”

“Did I…?” Her smile turned inward, became preoccupied. “Yes, I suppose I did.” She blinked, looked at me. “I told you the story of what happened at the hospital, with my friend, that night—I mean the night it all…”

“Yeah.” I nodded.

“There was one point when I was coming down the third floor corridor and my friend was at the other end, trying to open one of the doors. A young, male patient was helping her, who…what shall I say? Looked very much like you. I mean I was only with him for perhaps a minute. He was working very hard, trying to pry back this locked door with a piece of wood or metal—he had done something terrible to his hands. His hands were much smaller than yours; and the bandages had come loose from two of his fingers.” She grimaced. “But then some people needed help at the other end of the hall and he went off with them. I’d never seen him before—well, I was usually in the office. More sadly, I never saw him again. But when—how much later?—I saw you, in Teddy’s, that night with your face cut, then again, wandering around the park the next morning, barefoot, with your shirt hanging open, the resemblance struck me immediately. For a moment I thought you were the same person. And you’d helped us; so I wanted to help you—” She laughed. “So you see these—” she touched her own beads—“these really meant…nothing.”

I frowned. “You think maybe I’m…I was in the hospital here? That I never came here, from somewhere else? That I’ve been here all die—”

“Of course not.” Madame Brown looked surprised. “I said the young man looked something like you; he had something of your carriage, especially at a distance. He was about your size and coloring—maybe even a little smaller. And I’m sure his hair was dark brown, not black—though this was at night, by lights coming in the windows. I think, when he went away, someone—one of the other patients—called to him by name: I don’t remember what it was, now.” Her hands fell to her lap. “But that, anyway, is the real reason I offered you the job. I don’t know why, but I thought it might be a good time to clear that up.”

“I haven’t always been here,” I said. “I came here, over the bridge, over the river. And soon I’m going to leave. With Lanya and Denny…” It had felt very important to say.

“Of course,” Madame Brown said; but looked puzzled. “We all have to go on from where we are. And of course we’ve all come from where we’ve been. Certainly, at some point, you must have come here. More important, though, is not to get trapped in some circle of your own, habitual—” Outside, the dog barked. “Oh, that must be my next patient,” Madame Brown interrupted herself. The dog barked, kept barking.

Madame Brown frowned, half rose from the chair, one hand again absently at her beads. “Muriel!” she called; her voice was loud and low. “Muriel!”

It must have been something in the juxtaposition: the chains of lenses and prisms, or perhaps that she had said the beads meant nothing convinced me I was about to learn their real meaning; not that I was the person in the hospital but that somehow I or he…or that way she called the dog made me try to remember some place or some time when she, or someone else, had called it; not even my name, but possibly some other, if I could recall it—each element seemed about to explain the others, clearing the pattern; and that scratch…I got chills. I was being nudged, pushed, about to be reminded of…what? Anything more than the vast abysms of all our ignorances? Whatever, it was vastly sinister and breathlessly freeing. But I did not know; and that mystic ignorance wrung me out with gooseflesh.

“Well,” Madame Brown was saying. “Our time is about up. And I’m pretty sure that’s my next patient.”

“Okay.” I felt relieved too, somehow. “Hey, thanks a lot.”

“Would you like to arrange another—”

“No. Thanks, no, I don’t want to come back.”

“All right.” She stood up and considered saying something: Which, I guess, was: “Kid, please don’t think I’m smug. About you, or about any of the things we’ve talked about. I may not understand. But it’s not from not caring.”

I smiled. The gooseflesh rolled on—“I don’t think you’re smug—” and rolled away. “But I knew I wasn’t going to come here more than once—as a patient. So I had to get something for my troubles. I’ve spent a lot of time in therapy. And you have to know how to use it.” I laughed.

She smiled. “Good.”

“I’ll see you next time Lanya has Denny and me over for dinner—if not before. So long. Hey, if you want to talk about any of this with Lanya, go ahead.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t—”

“If she asks you anything, tell her what you think. Please.”

She pressed her lips a moment. “All right. Then it probably will provide us with at least thirty-six hours’ solid conversation.” She opened the door for me. “So long. I’ll see…Oh, hello…I’ll be with you in a few moments.”

“Sure.” The guy sitting on the desk corner, smiling up from the Newboy volumes, was the long-haired kid I’d seen cross-legged the night in the book-store basement, doing Om.

Madame Brown went back in her office and closed the door.

I went to the desk and picked up three of the books beside him. “I’m stealing these. Tell Madame Brown Lanya’ll bring them back if she really wants them…” I was going to say more, but even that sounded silly.

“Sure. I’ll tell Dr. Brown as soon as I go in.” Which made me wonder what he thought about me calling her “Madame.” I went into the hall. As I passed Muriel, sitting on the top step, watching me with gentled eyes, I heard the office door open.

I wrote all this down because today the page with the list of names on it is missing from the notebook. When I got back to the nest from the session, I started browsing through and I couldn’t find it. How many times have I read it over? I was planning to make myself read some of the Newboy. But as soon as I realized that page was gone, I suddenly felt an obsession to read it again, and began searching through the entries again and again on the chance I might have overlooked it. How many times have I read it before? (And now the only name I can remember from it is William Dhalgren.) At last, just to pull my mind away from it, I started writing out the above (and truncated) account of the hour Lanya arranged for me to have with Madame Brown, while she was off at her school. And what does it get me? The writing it down, I mean?

in their hands; the optic chain (a hundred feet? two hundred feet of it?), stretched among a dozen as they danced, glittered in beast light, sending flaked reflections along the undersides of leaves. Around us, they howled into the night, delighted, some going near the brazier, some going away.

Copperhead scrubbed at his mouth with his wrist. His eyes looked very red, his whole face burnished and flickering. “Hey, how do you like that?” he said. “Protection! That bastard Calkins wanted God-damn protection!” He turned from me to Glass. I laughed. Clapping perforated it. Copperhead looked up, suddenly; began to bellow and clap too, his palms hollowed. He was off rhythm so it carried a long way. He kept on bobbing his head to Glass’s bobbing head, till finally he got it, though he was laughing, now. Dragon Lady, beyond the toppled furnace, one boot propped on a fallen cinderblock, kneaded her shoulder, pensive and intent, watching the dance, her jade beast momentarily out.

Lanya turned and jumped, her blue shirt mapped with sweat; she held a chain high with one hand. She moved her harmonica across her mouth with the other, blowing discord after discord. Her forehead was glazed, her hair wet down her brow.

Jommy, I guess it was, broke out between Mildred and some bird of paradise (Cathedral shouting, “Hey, watch it—”), staggering into the dazzling web, and grabbed a strand for balance. Denny’s end—I jumped—broke (between mirror and prism) but he just whirled the loose length; finally looped it around somebody else’s strand and held it high with both hands. An end someone else had dropped snaked and jerked through fire-lit grass. I stepped forward, grabbed it up, and dodged beneath it, jumping from foot to foot and bellowing. D-t and Spider and Raven and Cathedral and Tarzan (he really can dance good as the niggers) and Jack the Ripper and Filament and Angel made a web: one strand vibrated; another went slack in catenaries between taut lengths. Gladis paused, with a fist full of green cloth over her great belly, swaying and breathing with her mouth wide. She ducked from a strand that tightened against her cheek, swung away, and began to clap.

I stopped shouting soon because my throat hurt; and heard, between the claps: “Bunny, whyn’t you get in there and show ’em how it’s done!”

“Don’t be silly, dear! We’ll just watch.”

“Naw, come on! I ain’t never really seen you dance.”

“Smile when you say that. Why don’t you?”

“Aw, come on. I wanna see what you can do.”

Something in the fire exploded; sparks shot above the flame tips, showering. The myriad narrow parabolas extinguished.

Dollar, his pimply back bright with sweat, stood centered in the clearing, feet wide, knees and head bent. Each clap detonated something in his belly that flung his hands, hips, and shoulders about.

Some of the commune kids were naked.

John danced with his brown beard up, his blond hair back, and his brass orchid waving on his hand overhead. A girl had gotten her legs caught in the chain going around, and fallen; she sat a long time, head forward, hair the color of dry leaves down across one breast. A few times she tried to stand. But another length of chain fell on her shoulder when someone dropped another end; she seemed too weighted to rise.

A griffin flickered twice: Adam bobbed and jerked. Chains and shocked hair swung and clattered and went out behind the reeling beast.

Bunny, barking shrill as a lap-dog, a dozen strands caught among up-thrust fingers, suddenly pranced forward, shaking back silver hair. Pepper, haunched behind him, followed, clapping and grinning like the devil.

An elderly black woman who’d brought some of the supper-boxes, stonily silent till now, cackled, beginning to clap too. The heavy, black-haired man with the bamboo flute had finally gotten out of his pants and danced up to her, trying to bring her into the circle. He piped and bobbed and bounced around: it was pretty phony and for a second I thought she would pinch his crank. But she got into it anyway and clapped for him—

And I stopped, landing on both heels, jarred to the scalp.

I turned in the furor, looking for someone (Thinking: Where did it come from…? Why now…? What…? then throwing that away and just trying to hold on to it); Lanya, shirt open and flapping, breasts shaking, eyes closed under quivering lids, turned to me behind at least five chains. I reached through them and caught her shoulders.

Her eyes snapped wide.

“Michael…” I said.

“What?”

A chain pulled down across my arm; a prism nipped my wrist. Lady of Spain was at one end, hauling.

“Mike Henry…” I looked down between my elbows at the trampled grass. “Michael Henry…?”

One of her bare feet moved. “What’s that?”

Very slowly, I said: “My first name is Mike…Michael. My middle name is Henry.” I looked up. “My last name—Fl…? Fr…?”

Lanya narrowed her eyes. Then she grabbed my forearm with the same hand her harmonica was in.

The edge bit; which brought me back: “What did I say?”

But she was looking around us, among the others. “Denny!”

“Lanya, what did I say?”

Her eyes snapped back to mine. She had a funny smile, intense and scared. “You said your first name was—” around us they clapped—“Michael. Your second name—” they clapped again—“is Henry. And your last…?”

My jaw clamped so hard my head shook. “I…I had it for a second! but then I…”

“It begins with ‘F’” She called again: “Denny!”

“Wait a minute! Wait, I…no, I can’t remember! But the first name—”

“—Michael Henry…” she prompted.

Denny ran up. “What…?” he put a hand on her shoulder, a hand on mine. “Come on, you wanna—”

“Tell him, Kid!”

I dropped Lanya’s elbows and took both of Denny’s.

He was breathing very hard. “My name is Michael—” another clap—“Henry…something. I don’t remember the last one now.” I took a deep breath (clap!). “But two out of three is pretty good!” I must have been grinning pretty hard.

“Wow!” Denny said. He started to say a couple of other things, but finally just shrugged, grinning back.

“I don’t know what to say either,” I said.

Lanya hugged me. She almost knocked me over.

Denny hugged us both, getting his head between ours and wiggling it back and forth and laughing. So Lanya had to hold him up with one hand. We all staggered. I put my arm around him too. Somebody pulled a chain against my back. It either broke or one of the people holding it let go. We staggered again.

Someone put hands against my back and said: “Hey, watch it! Don’t fall!” Paul Fenster—I hadn’t even seen him among the spectators—was steadying me as we came apart.

Re-reading this single description of Paul Fenster between these soiled cardboards, this thought: Since life may end at any when, the expectation of revelation or peripity, if not identical to, is congruent with insanity. They give life meaning, but expectation of them destroys our faculty for experiencing meaning. So I am still writing out these incidents. But now I am interested in the art of incident only as it touches life…but I have written that at least three other places among these pages. What I haven’t written is that, because of it, I am less and less interested in the incidence of art. (“Sex without guilt?” Entelechy without anticipation!) I just wonder would Paul have done anything differently that evening in the park if he’d known he was going to be shot in the head and neck four times, six hours later.

Lanya said: “It’s all right if we fall, Paul. It’s okay.”

Someone threw another length of chain into the circle. Manticore and iguanadon caught it up, blundering together, casting ghost-lights. Clap!

“Hey, I like your school,” Denny said. “I’ve been helping Lanya with her kids.”

“I was telling you about Denny, Paul? He was the one who suggested we take that class trip that turned out so well.”

I said: “I’ve never seen any children there. I’ve heard their voices. On the tape recorder. But I don’t believe you ever had any real children in there.”

Lanya looked at me oddly.

Fenster laughed. “Well, you brought us five of them yourself.”

“But there weren’t any…” Inside, it felt like two disjoined surfaces had suddenly slipped flush; the relief was unbearable. “I put five of them…in the school?”

“Woodard, Rose, Sammy…?” Lanya said.

“You remember,” Denny said. “Stevie? Marceline?”

“I remember,” I said. “I know who I am…”

“Michael Henry,” Denny said.

I put my hand on Fenster’s shoulder. “You go dance.”

“Naw, I’m not into the bare-ass bit.”

I frowned at the dancers; only fifteen or twenty were naked.

“Go on.” I pushed at him; he stepped back. “You don’t have to take your clothes off. You just go dance.”

Fenster looked at Lanya. To stand up for him? I flashed on him pulling her shirt closed across her breasts, buttoning the top button, patting her head, and walking away.

“Go ahead.” I was angry. “Dance!”

“Come on, Kid,” Lanya said, taking my arm.

Fenster walked off now, laughing.

“You wanna sit down?” Denny asked.

“Come on,” Lanya said. “Let’s go sit down.”

Denny took my other arm; but I twisted to look back.

Fenster walked between the dancers, now pushed, now helping a girl wearing just a sopping T-shirt who fell against him, now ducking beneath one of the glittering lines pulled between bright creatures prancing at the tree.

“What are you trying to do?” Lanya asked.

“Take off my clothes. I don’t need anything…anything now.” I tossed my boot on top of my vest. I lifted my chin and raised the seven chains and the projector. Links dragged my nipples. I held them up, swaying, and let go. Some hit my nose and cheek and ear. Some fell across my shoulder, and slid off, clattering, to the grass. I looked down to undo the twin hooks on my belt; pushed down my pants. Lanya held my arm so I wouldn’t fall getting my foot out the cuff.

“Feel better?” Denny asked.

I tried to undo the clasp at the side of my neck. A file of insects, it felt like, charged down my belly, caught in the hair of my groin. The optic chain sagged around my ankle.

“I think you broke it,” Lanya said.

“I can fix it again,” Denny said. “I got nails—”

“No,” I said.

From the commune, from the nest, and from the people who’d just come to watch, they clapped and leaped beside the fire. Seven more, barking, calling, and yipping, broke from the loose ring, turned among and beneath (one very black girl jumped over) the beaded chain that crossed and crossed the clearing. The heads of beasts blown out of light like glass broke scarves of smoke; our throats tickled from the harsh air.

Three silhouetted figures, heads together, came toward me, whispering. Copperhead, center, conferred with Raven and Cathedral. Raven and Copperhead were naked. (The different curl and color of their hair, suddenly bright at the sides of their heads with the fire behind them…) Copperhead had his hand on Raven’s shoulder.

Copperhead was saying: “Protection! Did you get that? Calkins asking for protection—?”

Cathedral said: “Scorpions don’t protect nothing.”

Copperhead said: “They shot out practically every God-damn window in the God-damn fucking building. Man, it was something!”

Raven asked: “They shot up Calkins’s place? The sniper…?”

Copperhead said: “Not Calkins’ place! And it weren’t no fuckin’ sniper! It was them people back at that big store. You remember that big fuckin’ apartment house Thirteen used to be in, up on the sixteenth floor? God damn, man, they shot the whole fuckin’ place up, practically every God-damn window in the building!”

“Shit, man!” Cathedral shook his head. “The honkeys is bad as the niggers.”

Copperhead humphed: “Protection!”

Raven laughed.

They walked away in the dark.

I watched the fire. One pants leg was still around my ankle. The optic chain, as I swayed, swayed against my calf. “I want to…to dance.”

“Then get your foot out your pants cuff,” Denny said. “You’ll trip yourself.” He sounded like he didn’t want me to go, though.

Each Clap! struck something inside my skull that made a flash all its own. My ears thundered as though only inches from the drum. Each explosion left some crazy echo stuttering in the tattered noise. I stepped forward, moiling my genitals in my hand. They felt sensitive. I stepped again.

“Watch it—”

Lanya must have held my pants leg down with her foot, because they came off. I stumbled, but kept going. Toward the dance.

In a black turtleneck sweater he stood, with folded arms, among the spectators. He didn’t see me looking at him. But Lady of Spain and D-t and a couple of others did and stopped dancing. Prisms and lenses hung down from my neck. Mirrors and prisms swung from my wrist. Lenses and mirrors dragged from my ankle behind me in the grass.

He shifted a little. Firelight shook its patina across his brown hair.

“Hey…!” I said loudly. “I know who I…who I am now. Who are you?”

He looked at me, frowning.

“Who are you?” I repeated. “Tell me. I know who I am!” A few more dancers stopped to listen. But the clapping was still awfully loud. I shook my head. “Almost…”

“Kid?” he asked; it had taken him until then to recognize me, naked. “Hey, Kid! How’re you doing?”

It was the man who’d interviewed me at Calkins’ party.

“No,” I said. “I know who I am. You say who you are.”

“William…” he began. “Bill…?” And then: “You don’t remember me?”

“I remember you. I just want to know who you are!”

“Bill,” he repeated. And nodded, smiling.

Two people who’d stopped to listen began to clap again.