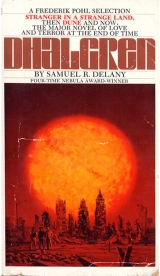

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

With darkness in his eyes, the red memory was worse than the discovery.

On the third landing, he slipped, and fell, clutching the rail, the whole next flight. And still did not slow. He made it through the corridors at the bottom (warm concrete under his bare foot) on kinesthetic memory. He tore up the bannisterless stair, slapping at the wall, till he saw the door ahead, charged forward; he came out under the awning, running, and almost impaled himself on the dangling hooks.

Averting his face, he swung his arm against them—two clashed, trundling away on their rails. At the same time, his bare foot went off the porch’s concrete edge.

For one bright instant, falling, he thought he was going to do a belly-whop on the pavement, three feet down. Somehow, he landed in a crouch, scraping one hand and both knees (the other hand waving out for balance) before he pushed up, to stagger from the curb.

Gasping, he turned to look back up at the loading porch.

From their tracks, under the awning, the four and six-foot butcher hooks swung.

Blocks away, a dog barked, barked, barked again.

Still gasping, he turned, and started walking toward the corner, sometimes with his sandaled foot on the curb, mostly with both in the gutter.

Nearly there, he stopped, raised his hand, stared at the steel blades that curved from the plain wrist band to cage his twitching fingers. He looked back at the loading porch, frowned; looked back at the orchid on his hand: he felt the frown, from inside; a twisting in his facial flesh he could not control.

He remembered snatching up his pants. And his shirt. And his sandal. He remembered going down the dark stair. He remembered coming up and out on the porch, hitting at the hooks, and falling—

But nowhere in the past moments did he recall reaching behind two asbestos-covered pipes, fitting his fingers through the harness, clamping the collar to his wrist…

He reviewed: pants, shirt, sandal, the dark stair—down, across, up. Light from the door; the racketing hooks; his stinging palm.

He looked at his free palm; scraped skin was streaked grey…He looked down the block. There were no vehicles anywhere on the street…

No. Go back.

Warm concrete under his foot. His sandal clacking. Slapping the wall; coming up. Seeing the doorway. Seeing the pipes…! They were on the left-hand side of the doorway. The blistered covering was bound with metal bands! On the thicker one, near the ceiling, hadn’t there been some kind of valve? And had rushed past them, onto the concrete, nearly skewered himself; hit with his forearm—it was still sore. He was falling…

He was turning; missed the curb, staggered, shook his head, looked up.

The street sign on the corner lamppost said Broadway.

“…goes up into the city and…” Someone had said that. Tak?

But no…

…seeing the light. Ran out the door. The hooks…

The muscles in his face snarled on chin and cheekbones. Suddenly tears banked his eyes. He shook his head. Tears were on his cheek. He started walking again, sometimes looking at one hand, sometimes at the other. When he finally dropped his arms, blades hissed by one jean thigh—

“No…”

He said that out loud.

And kept walking.

Snatched his clothes from the floor, jammed his feet into his pants; stopped just outside the shack (leaning against the tarpaper wall) for his sandal. Around the skylight; one sleeve. Into the dark; the other. Running down steps—and he’d fallen once. Then the bottom flight; the warm corridor; coming up; slapping; he’d seen light before he’d reached the top, turned, and seen the day-bright doorway (the big pipe and the little pipe to one side), run forward, out on the porch, beat at the hooks; two trundled away as his bare foot went over. For one bright moment, he fell—

He looked at his hands, one free, one caged; he looked at the rubble around him; he walked; he looked at his hands.

A breath drained, roaring, between tight teeth. He took another.

As he wandered blurred block after blurred block, he heard the dog again, this time a howl, that twisted, rose, wavered, and ceased.

II The Ruins of Morning

HERE I AM AND AM NO I. This circle in all, this change changing in winterless, a dawn circle with an image of, an autumn change with a change of mist. Mistake two pictures, one and another. No. Only in seasons of shortlight, only on dead afternoons. I will not be sick again. I will not. You are here.

He retreated down the halls of memory, seething.

Found, with final and banal comfort—Mother?

Remembered the first time he realized she was two inches taller than his father, and that some people thought it unusual. Hair braided, Mother was tolerant severity, was easier to play with than his father, was trips to Albany, was laughter (was dead?) when they went for walks through the park, was dark as old wood. More often, she was admonitions not to wander away in the city, not to wander away in the trees.

Father? A short man, yes; mostly in uniform; well, not that short—back in the force again; away a lot. Where was Dad now? In one of three cities, in one of two states. Dad was silences, Dad was noises, Dad was absences that ended in presents.

“Come on, we’ll play with you later. Now leave us alone, will you?”

Mom and Dad were words, lollying and jockeying in the small, sunny yard. He listened and did not listen. Mother and Father, they were a rhythm.

He began to sing, “Annnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnn…” that had something of the fall of words around. “Annnnnnn—”

“Now what are you going on like that for?”

“Ain’t seen your mom in two weeks. Be a good boy and take it somewhere else?”

So without stopping he took his Annnnnnnnnn down the path beside the house where hedge-leaves slapped his lips and tickled them so that he took a breath and his sound snagged on laughter.

ROAR and ROAR, ROAR: he looked up. The planes made ribs across the sky. The silver beads snagged sun. The window wall of his house blinded him so—“Annnnnnnn…”—he made his noise and gave it the sound of the planes all up and down the street, walking and jogging with it, in his sneakers, and went down the steps at the side of the street, crossed over. His sound buzzed all the mask of his face. Shadows slid over him: he changed sound. Shadows slid away: he changed it back. The sun heated the bony spots above his eyes; that changed it again; and again, when the birds (he had wandered into the woods that lapped like a great tongue five blocks into town; soon he had been in them for a quarter of an hour) collided in the leaves, then flung notes down. One note was near enough; he caught it with his voice and it thrust him toward another. Sun and chill (spring had just started) cuffed and pummeled him and he sang, getting pine needles inside his canvas shoes (no socks) and the back of his neck tickling from hair when the wind came.

He climbed the rocks: his breath made windy pauses in the sound and that was interesting, so that when he reached the top he pushed the leaves away and made each note as low as the green whisper—

Three of the five were naked.

Which stopped him.

And one girl was wearing only a little cross around her neck. The silver tilted on the inner slope of one breast. She breathed.

He blinked and whispered another note.

Silver broke up the sun.

The man still in pants pushed one fist up into the foliage (pants undone, his belt lay free of half its loops, away from his hip), pushed his other hand down to scratch, twisting his hips so that more and more, stretching in the green—

The girl who was darker even than his mother rolled to her side: someone else’s yellow hair fell from her back and spread. And her hands on the man’s face were suddenly hidden by his hands on hers (in the pile of clothing he recognized another uniform, but blue-black where his father’s was green) and she was moving against him now, and there was a grass blade against her calf that slipped first one way, then the other.

He held his breath, forgot he was holding it: then it all came out in a surprising at-once that was practically not a note at all. So he got more air back in his lungs and began another.

“Hey, look!” from the other naked one, on elbows and laughing: “We got company!” and pointing.

So his sound, begun between song and sigh, ended in laughter; he ran back through the brush, pulling a music from their laughing till his was song again. He cantered down the path.

Some boys came up the path (this part of the wood was traveled as any park), thumbs in their jeans, hair all points and lines and slicks. Two of them were arguing (also, he saw as they neared, one of the boys was a girl), and one with carroty hair and small eyes glared at him.

He hunched, intently, and didn’t look back at them, even though he wanted to. They were bad kids, he decided. Dad had told him to stay away from bad kids.

Suddenly he turned and sang after them, trying to make the music stealthy and angular till it became laughter again. He had reached the playground that separated the woods from town.

He mixed his music with the shouting from the other side of the fence. He rippled his fingers on the wire and walked and looked through: Children clustered at the sliding board. But their scuffle had turned to shouts.

Beyond that were street sounds. He walked out among them and let his song pick them up. Cars, and two women talking about money, and something bang-banging in the big building with the corrugated walls: emerging from that, foot-rhythms. (Men in construction-helmets glanced at him.) That made him sing louder.

He walked up a hill where the houses got bigger, with lots of rock between. Finally (he had been flipping his fingers along the iron bars of the gate) he stopped to really look in (now going Hummmm, and hmmmmm, hmmmm, and hmmmmm) at the grass marked with tile squares, and a house that was very big and mostly glass and brick. A woman sat between two oaks. She saw him, cocked her head curiously, smiled—so he sang for her Ahhhhhhhhh—she frowned. He ran down the street, down the hill, singing.

The houses weren’t so big anymore.

The ribs of day cracked on the sky. But he didn’t look up at the planes this time. And there were lots more people.

Windows: and on top of the windows, signs: and on top of the signs, things that turned in the wind: and on top of those, blue where wind you couldn’t see went—

“Hey, watch it—”

He staggered back from a man with the dirtiest wrists he had ever seen. The man repeated: “Watch where you’re God-damn going—” to nobody, and lurched away. He was going to turn and run down the next street…

The bricks were cracked. A plank had come away from the window.

Trash heaped beside the door.

No wind, and warm; the street was loud with voices and machinery, so loud he could hardly catch rhythm for his song.

His sounds—long and lolling over his tongue now—were low, and he heard them under, not over, the noise.

“Hey, look out—”

“What the—”

“Hey, did you see that—”

He hadn’t.

“What are you—”

People turned. Somebody ran past him close, slapping black moccasins on the stone.

“Those bastards from the reservation!”

“That’s one of their kids, too.”

He wasn’t; and neither was his mother—she was from…? Anyway, he tried to sing that too, but was worried now. He turned the corner into an alley crowded with warm-weather loungers.

Two women, bony and delighted, stood in the doorway:

One: “Did you see that?”

The other laughed out loud.

He smiled; that changed his sound again.

From the next doorway, fat and ragged, face dirty as the drunkard’s wrists, she carried a cloth bag in one fist, with the other beat at the trash. She turned, lumbering in the heap, blinked at him.

His music stuttered, but took it in. He hurried onto the avenue, dodged around seven nuns, started to run, but turned to watch them.

They walked slowly and talked quickly, with sharp small voices. Falls of white broke at breast and knee; black scuffed toes wrinkled white hems.

People stepped around them.

“Good morning, sisters.”

Sisters nodded and smiled, probably because it was afternoon. They walked straight, brushing and brushing.

He tried to fit the rhythm of their walk into his music. He glanced around the street, hurried on, making his sounds longer and longer; hurried till he was running and each note took half a block.

Ran around another corner.

And all his breath came hissing between his teeth.

The man’s palm lifted, his fingertips stayed down to draw wet lines on the pavement, before he rolled over to show most of the wound. The one standing swayed and sweated. When the woman at the other corner began to call out, “Ohma’god! Ohma’god, he-e-elp!” the standing man ran.

He watched him run, and screamed, a little, twice.

The man on the street was grunting.

Someone running joggled him, and he stepped back, with another sound; then he ran too and what had begun as music was now a wail. He ran until he had to walk. He walked until he had to stop singing. Then he ran again: throat raw, he wailed again.

Once he passed a clutch of unshaven men; one pointed at him, but another put a bottle in the hand shucked with purple.

He ran.

He cried.

He cut across the corner of the woods. He ran some more.

He ran on the wide street under a ribbon of evening. Lights came on like twin necklaces suddenly unrolled down the avenue, traffic and tail beacons between. He shrieked. And fled from the street because people were looking.

This street was more familiar. Noise hurt his throat. Sharp lights in his eyes; hedges marred with darkness. And he was roaring now—

“For God’s sake—!”

He came up hard against her hands! Mother, and he tried to hug her, but she was holding him back.

“Where have you been? What is the matter with you, shouting around in the street like that?”

His mouth snapped. Sound to deafen built behind his teeth.

“We’ve been looking for you nearly half the day!”

None of it escaped. He was panting. She took his arm and led him.

“Your father—” who was turning the corner now—“comes home the first time in two weeks, and you decide to go running off!”

“There he is! Where did you find him!” and his father laughed and that at least was some sound. But not his.

They received him with scolding affection. But more vivid was the scalding energy he could not release. Wanting to cry, he had been silent, chewed on his knuckles, the heels of his palms, his cuticles, and what was left of his nails.

These memories intact solved as little as those riddled with gaps. Still, he rose from them, reassured.

He hunted over them for his name. Once, perhaps, his mother calling, from across a street…

No.

And memory was discarded:

How can I say that that is my prize possession? (They do not fade, neither those buildings nor these.) Rather what we know as real is burned away at invisible heat. What we are concerned with is more insubstantial. I do not know. It is as simple as that. For the hundredth time, I do not know and cannot remember. I do not want to be sick again. I do not want to be sick.

This lithic grin…?

Not on the lions he’d walked between last night with Tak.

Vaguely he thought he’d been wandering toward the river. But somehow chance, or bodily memory, had returned him to the park.

Inside the entrance was ashy grass; dimmed trees forested the crest.

He turned his forefinger in his nostril, put it in his mouth for the salt, then laughed and pressed his palm on the stone jaw; moved his hand. Stain passed between his fingers. The sky—he’d laughed, flung up his head—did not look infinitely far; a soft ceiling, rather, at some deceptive twenty, a hundred twenty feet. Oh, yes, laughter was good. His eyes filled with the blurry sky and tears; he moved his hand on the pitted jaw. When he took his palm from the dense braille, he was breathing hard.

No gushing breeze over this grass. His breath was thin, hoarse, suggestive of phlegm and obstacles and veins. Still, he’d laughed.

The sculptor had dug holes for eyes too deep to spot bottom.

He dug his finger in his nose again, sucked it, gnawed it; a gusty chuckle, and he turned through the leonine gate. It’s easy, he thought, to put sounds with either white (maybe the pure tone of an audio generator; and the other, its opposite, that was called white noise), black (large gongs, larger bells), or the primary colors (the variety of the orchestra). Pale grey is silence.

A good wind could wake this city. As he wandered in, buildings dropped behind him below the park wall. (He wondered what ill one had put it to sleep.) The trees waited.

This park stretches on racks of silence.

In his mind were some dozen visions of the city. He jogged, jaggedly, among them. His body felt hip heavy. His tongue lay down like a worm in his mouth. Breath in the cavity imitated wind; he listened to the air in his nose since that was all there was to listen to.

In its cage, his fist wilted, loose as a heavy flower.

Mornings after sex usually gave him that I’ve-been-eating-the-lotus-again, that Oh-all-soft-and-drifty, that hangover-inside-out where pain is all in the world and the body tingly and good. Delayed? But here it was. The commune? Debating whether to hunt them or avoid them, he found the water fountain.

He spat blood-laced amber clots. Water tugged them from the pebbly basin. The next were greenish and still gum bloody. He frothed the water, bitter with what was under his tongue, through his teeth and spat and spat till he spat clear. His lips tingled. Yeah, and felt better.

He left the fountain, gazing on grey, his belly cooler, blades whispering at his jeans. Across the damask of doubt and hesitation was unexpected joy like silver.

Something…He’d survived.

He pranced on the hill, happily oblivious to heart and bowels and the rest of the obstreperous machinery. This soft, this ecstatic grey, he swung through, in lop-looped chain, tasting the sweet smoke, buoyed on dusty grass.

The long, metallic note bent, broke to another. Someone was playing the harmonica—silver? Artichokes? Curiosity curved through, pressed down his mouth at both corners.

Like some color outside this grey range, music spilled the trees. He slowed and walked wonderingly into them. His feet came down in hushing puddles of grass. He frowned left and right and was very happy. The notes knotted with the upper branches.

In a tree? No…on a hill. He followed around the boulders that became a rise. The music came down from it. He looked up among leaf-grey and twig-grey. Picture: the harp leaving the lips, and the breath (leaving the lips) become laughter. “Hello,” she called, laughing.

“Hello,” he said and couldn’t see her.

“Were you wandering around all night?”

He shrugged. “Sort of.”

“Me too.”

While he realized he had no idea of her distance, she laughed again and that turned back into music. She played oddly, but well. He stepped off the path.

Waving his right hand (caged), grasping saplings with his left (free), he staggered on the slope. “Hey…!” because he slipped, and she halted.

He caught up balance, and climbed.

She played again.

He stopped when the first leaves pulled from her.

She raised her apple eyes—apple green. Head down, she kept her lips at the metal organ.

Roots, thick as her arms, held the ground around her. Her back was against a heavy trunk. Leaves hid her all one side.

She wore her shirt. Her breasts were still nice.

His throat tightened. He felt both bowels and heart now; and all the little pains that defined his skin. It’s stupid to be afraid…of trees. Still, he wished he had encountered her among stones. He took another step, arms wide for the slant, and she was free of foliage—except for one brown leaf leaning against her tennis shoe.

“Hi…”

A blanket lay beside her. The cuffs of her jeans were frayed. This shirt, he realized, didn’t have buttons (silver eyelets on the cloth). But now it was half laced. He looked at the place between the strands. Yes, very nice.

“You didn’t like the group last night?” She gestured with her chin to some vague part of the park.

He shrugged. “Not if they’re going to wake me up and put me to work.”

“They wouldn’t have, if you’d pretended to be asleep. They don’t really get too much done.”

“Shit.” He laughed and stepped up. “I didn’t think so.”

She hung her arms over her knees. “But they’re good people.”

He looked at her cheek, her ear, her hair.

“Finding your way around Bellona is a little funny at first. And they’ve been here a while. Take them with a grain of salt, keep your eyes open, and they’ll teach you a lot.”

“How long have you been with them?” thinking, I’m towering over her, only she looks at me as though I’m too short to tower.

“Oh, my place is over here. I just drop in on them every few days…like Tak. But I’ve just been around a few weeks, though. Pretty busy weeks.” She looked through the leaves. When he sat down on the log, she smiled. “You got in last night?”

He nodded. “Pretty busy night.”

Something inside her face fought a grin.

“What’s…your name?”

“Lanya Colson. Your name is Kidd, isn’t it?”

“No, my name isn’t Kidd! I don’t know what my name is. I haven’t been able to remember my name since…I don’t know.” He frowned. “Do you think that’s crazy?”

She raised her eyebrows, brought her hands together (he remembered the remains of polish: so she must have redone them this morning: her nails were green as her eyes) to turn the harmonica.

“The Kid is what Iron Wolf tried to name me. And the girl in the commune tried to put on the other ‘d’. But it isn’t my name. I don’t remember my God-damn name.”

The turning halted.

“That’s like being crazy. I forget lots of other things. Too. What do you think about that?” and didn’t know how he would have interpreted his falling inflection either.

She said: “I don’t really know.”

He said, after the silent bridge: “Well, you have to think something!”

She reached into the coiled blanket and lifted out…the notebook? He recognized the charred cover.

Biting at her lip, she began ruffling pages. Suddenly she stopped, handed it to him—“Are any of these names yours?”

The list, neatly printed in ballpoint, filled two columns:

Geoff Rivers

Arthur Pearson

Kit Darkfeather

Earlton Rudolph

David Wise

Phillip Edwards

Michael Roberts

Virginia Colson

Jerry Shank

Hank Kaiser

Frank Yoshikami

Garry Disch

Harold Redwing

Alvin Fischer

Madeleine Terry

Susan Morgan

Priscilla Meyer

William Dhalgren

George Newman

Peter Weldon

Ann Harrison

Linda Evers

Thomas Sask

Preston Smith

“What is this shit?” he asked, distressed. “It says Kit, with that Indian last name.”

“Is that your name after all?”

“No. No, it’s not my name.”

“You look like you could be part Indian.”

“My mother was a God-damn Indian. Not my father. It isn’t my name.” He looked back at the paper. “Your name’s on here.”

“No.”

“Colson!”

“My last name. But my first name’s Lanya, not Virginia.”

“You got anybody in your family named Virginia?”

“I used to have a great aunt Virgilia. Really. She lived in Washington D.C. and I only met her once when I was seven or eight. Can you remember the names of anybody else in your family? Your father’s?”

“No.”

“Your mother’s?”

“…what they look like but…that’s all.”

“Sisters or brothers?”

“…didn’t have any.”

After silence he shook his head.

She shrugged.

He closed the book and searched for speech: “Let’s pretend—” and wondered what was in the block of writing below the lists—“that we’re in a city, an abandoned city. It’s burning, see. All the power’s out. They can’t get television cameras and radios in here, right? So everybody outside’s forgotten about it. No word comes out. No word comes in. We’ll pretend it’s all covered with smoke, okay? But now you can’t even see the fire.”

“Just the smoke,” she said. “Let’s pretend—”

He blinked.

“—you and I are sitting in a grey park on a grey day in a grey city.” She frowned at the sky. “A perfectly ordinary city. The air pollution is terrible here.” She smiled. “I like grey days, days like this, days without shadows—” Then she saw he had jabbed his orchid against the log.

Pinioned to the bark, his fist shook among the blades.

She was on her knees beside him: “I’ll tell you what let’s do. Let’s take that off!” She tugged at the wrist snap. His arm shook in her fingers. “Here.” Then his hand was free.

He was breathing hard. “That’s—” he looked at the weapon still fixed by three points—“a pretty wicked thing. Leave it the fuck alone.”

“It’s a tool,” she said. “You may need it. Just know when to use it.” She was rubbing his hand.

His heart was slowing. He took another, very deep breath. “You ought to be afraid of me, you know?”

She blinked. “I am.” And sat back on her heels. “But I want to try out some things I’m afraid of. That’s the only reason to be here. What,” she asked, “happened to you just then?”

“Huh?”

She put three fingers on his forehead, then showed him the glistening pads. “You’re sweating.”

“I was…very happy all of a sudden.”

She frowned. “I thought you were scared to death!”

He cleared his throat, tried to smile. “It was like a…well, suddenly being very happy. I was happy when I walked into the park. And then all of a sudden it just…” He was rubbing her hand back.

“Okay.” She laughed. “That sounds good.”

His jaw was clamped. He let it loosen, and grunted: “Who…what kind of a person are you?”

Her face opened, with both surprise and chagrin: “Let’s see. Brilliant, charming—eight—four pounds away from being stunningly gorgeous…I like to tell myself; family’s got all sorts of money and social connections. But I’m rebelling against all that right now.”

“Okay.”

Her face was squarish, small, not gorgeous at all, and it was nice too.

“That sounds accurate.”

The humor left it and there was only surprise. “You believe me? You’re a doll!” She kissed him, suddenly, on the nose, didn’t look embarrassed, exactly; rather as though she were timing some important gesture.

Which was to pick up her harmonica and hail notes in his face. They both laughed (he was astonished beneath the laughter and suspected it showed) while she said: “Let’s walk.”

“Your blanket…?”

“Leave it here.”

He carried the notebook. They flailed through the leaves, jogging. At the path he stopped and looked down at his hip. “Uh…?”

She looked over.

“Do you,” he asked slowly, “remember my picking up the orchid and putting it on my belt here?”

“I put it on there.” She thumbed some blemish on the harmonica. “You were going to leave it behind, so I stuck a blade through your belt loop. Really. It can be dangerous around here.”

Mouth slightly open, he nodded as, side by side, they gained the shadowless paths.

He said: “You stuck it there.” Somewhere a breeze, without force, made its easy way in the green. He was aware of the smoky odor about them for two breaths before it faded with inattention. “All by yourself, you just found those people in the park?”

She gave him a You-must-be-out-of your-mind look. “I came in with quite a party, actually. Fun; but after a couple of days they were getting in the way. I mean it’s nice to have a car. But if you’re rendered helpless by lack of gasoline…” She shrugged. “Before we got here, Phil and I were taking bets whether this place really existed or not.” Her sudden and surprising smile was all eyes and very little mouth. “I won. I stayed with the group I came in with awhile. Then I cut them loose. A few nights with Milly John, and the rest. Then I’ve been off having adventures—until a few nights ago, when I came back.”

Thinking: Oh—“You had some money when you got here?”—Phil.

“Group I came with did. A lot of good it did them. I mean how long would you wander around a city like this looking for a hotel? No, I had to let them go. They were happy to be rid of me.”

“They left?”

She looked at her sneaker and laughed, mock ominous.

“People leave here,” he said. “The people who gave me the orchid, they were leaving when I came.”

“Some people leave.” She laughed again. It was a quiet and self-assured and intriguing and disturbing laugh.

He asked: “What kind of adventures did you have?”

“I watched some scorpion fights. That was weird. Nightmare’s trip isn’t my bag, but this place is so small you can’t be that selective. I spent a few days by myself in a lovely home in the Heights: which finally sent me up the wall. I like living outdoors. Then there was Calkins for a while.”

“The guy who publishes the newspaper?”

She nodded. “I spent a few days at his place. Roger’s set up this permanent country weekend, only inside city limits. He keeps some interesting people around.”

“Were you one of the interesting people?”

“I think Roger just considered me decorative, actually. To amuse the interesting ones. His loss.”

She was pretty in a sort of rough way—maybe closer to “cute.”

He nodded.

“The brush with civilization did me good, though. Then I wandered out on my own again. Have you been to the monastery, out by Holland?”

“Huh?”

“I’ve never been there either, but I’ve heard some very sincere people have set up a sort of religious retreat. I still can’t figure out if they got started before this whole thing happened, or whether they moved in and took over afterward. But it still sounds impressive. At least what one hears.”

“John and Mildred are pretty sincere.”

“Touché!” She puffed a chord, then looked at him curiously, laughed, and hit at the high stems. He looked; and her eyes, waiting for him to speak, were greener than the haze allowed any leaf around.

“It’s like a small town,” he said. “Is there anything else to do but gossip?”

“Not really.” She hit the stems again. “Which is a relief, if you look at it that way.”

“Where does Calkins live?”

“Oh, you like to gossip! I was scared for a moment.” She stopped knocking the stalks. “His newspaper office is awful! He took some of us there, right to where they print it. Grey and gloomy and dismal and echoing.” She screwed up her face and her shoulders and her hands. “Ahhhh! But his house—” Everything unscrewed. “Just fine. Right above the Heights. Lots of grounds. You can see the whole city. I imagine it must have been quite a sight when all the street lights were on at night.” A small screwing, now. “I was trying to figure out whether he’s always lived there, or if he just moved in and took it over too. But you don’t ask questions like that.”