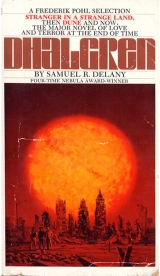

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“Yes…yes, that’s happened to me.”

“Well, I think all the buildings and the bridges and the planes and the books and the symphonies and the paintings and the spaceships and the submarines and…and the poems: they’re just to keep people’s minds occupied so it doesn’t happen—again.” After a while he said: “George Harrison…”

She said: “June Richards…” and glanced at him. When he said nothing, she said: “I have this picture, of us going down to the bar one night, and you saying, ‘Hey, man, come on with me. I want you to meet a friend of mine,’ and George says, ‘Why sure!’—and he probably would, too; he knows how small the world is he’s acting moon for—so you take him, in all his big, black, beautiful person up to that pink brick high-rise with all the broken windows and you get a-hold of Miss Demented-sweetness-and-light, and you say, ‘Hey, Llady, I’ve just brought you His Midnight Eminence, in the flesh. June, meet George. George, meet June.’ I wonder what they’d talk about—on her territory?”

He chuckled. “Oh, I don’t know. He might even say, Thank you. After all, she made him what he is today.” He blinked at the leaves. “It’s fascinating, life the way it is; the way everything sits together, colors, shapes, pools of water with leaves in them, reflections on windows, sunlight when there’s sun, cloudlight when it’s cloudy; and now I’m somewhere where, if the smoke pulls back at midnight and George and the moon are up, I might see two shadows instead of one.” He stretched his hands behind him on the blanket. He knocked something—which was his orchid, rolling across his notebook cover.

“When I was at Art School,” she said, “I remember an instructor of mine saying that it was only on days like you have here that you know the true color of anything. The whole city, all of Bellona, it’s under perpetual north light.”

“Mmm,” he said.

What is this part of me that lingers to overhear my own conversation? I lie rigid in the rigid circle. It regards me from diametric points, without sex, and wise. We lie in a rigid city, anticipating winds. It circles me, intimating only by position that it knows more than I want to. There, it makes a gesture too masculine before ecstatic scenery. Here, it suggests femininity, pausing at gore and bone. It dithers and stammers, confronted by love. It bows a blunt, mumbling head before injustice, rage, or even its like ignorance. Still, I am convinced that at the proper shock, it would turn and call me, using those hermetic syllables I have abandoned on the crags of a broken conscience, on the planes of charred consciousness, at the entrance to the ganglial city. And I would raise my head.

“You…” he said, suddenly. It was dark. “Are you happy, I mean, living like this?”

“Me?” She breathed a long breath. “Let me see…before I came here, I was teaching English to Cantonese children who’d just arrived in New York’s Chinatown. Before that, I was managing a pornographic bookstore on 42nd Street. And before that, for quite a while, I was a self-taught tape-jockey at WBAI-FM, in New York, and before that, I was doing a stint at her sister station KPFA, in Berkeley, Cal. Babes, I am so bored here that I don’t think, since I’ve come, I’ve ever been more than three minutes away from some really astonishing act of violence.” And suddenly, in the dark, she rolled against him.

“Gotta run.” Click. The tie knot rose.

“Hey, Mr. Richards?” Kid put down his own cup.

“Yes, Kidd?” Mr. Richards, already in the doorway, turned back. “What do you want?”

Bobby spooned at his frosted cereal. There was no milk. June traced a column in the Friday, October 24, 1985 Times with her forefinger. It was several weeks old.

“I want to know about my money.”

“You need some more? I’ll have some for you when I get home this evening.”

“I want to know how much I’m getting.”

“Hm? Oh. Well, we’ll have to figure that out. Have you been keeping track of how long you’ve been working each day?”

“More or less,” Kidd said. “Madame Brown told me you were going to give me five bucks an hour.”

Mr. Richards took the door knob. “That’s pretty high wages.” He shook his head, thoughtfully.

“Is that what you told her?”

The knob turned. “We better talk about it later on this evening.” The door closed on his smile.

Kidd turned back to Mrs. Richards.

She sipped, eyes flickering above the china rim.

“I mean that’s what you told her, isn’t it?”

“Five dollars an hour is quite high. For unskilled labor.” The cup lowered to her chin.

“Yeah, but not for furniture movers. Look, let me go downstairs and finish bringing up the rugs and the clothes. It’s only going to take another half-dozen trips. I’ll be through before you get started on lunch.” Kidd got up too noisily and went to the door.

Bobby’s spoon, silent the exchange, crunched again.

June’s eyes had stayed down, but once more her finger moved.

From the doorway Kidd glanced back at her (as moments before her father had glanced back at him) and tried to set her against George’s and Lanya’s conversation of the previous afternoon. But, with blonde head and pink reflection fuzzed in the polish, she seemed wholly at home among the fluted, white china cups, the brass pots of plants, the green mats, the blue flowered drapes, her mother, her brother, the wide windows, or the green wallpaper with its paler green florals.

Down on seventeen, he came into the apartment (unchained, unlocked) and thought: Why didn’t we take the rugs up first? That was silly, not to have taken the rugs up. Like mottled eels (the underpad, a smaller darker eel, printed with a design that, till now, he’d only seen on corrugated ceilings) the rugs lay against the living room wall. Outside the window, pale leviathans swam. Piles of books sat on the floor.

Pilgrimage was on top of one.

For the third—or was it the fourth? Or the fifth?—time he picked it up, read at random pages, waiting to be caught and driven into the work. But the receptivity he tried to bring was again and again hooked away by some pattern of shadow on the bare vinyl tile, some sound in the apartment below, some itch on his own body: and there went all his attention. Though his eye moved over the print, his place and the print’s sense were lost: At last he lay the book back on the pile, and put a book from another pile on top, as though—and wondered why he thought of it this way—the first book were his own.

He stood up—he had been squatting—and gazed around: still to be moved were bridge tables from the back storage closet, folding chairs with scrolled arms, green cushions, and black metal hinges; and toys from Bobby’s room, scattered among them. A set of four nest tables was crowded with small, bright breakables.

He wandered down the hall (there was the carton of papers from Mr. Richards’ den) and turned into Bobby’s room. Most of what was left was evidence of the older brother who’d once shared it: a handkerchief that had fallen out of a bureau drawer yesterday, showing the monogram: EGR; propping the closet door were three small cartons with Eddy written across them in magic marker; on the floor was the Bellona High School Yearbook. Kidd picked it up and paged through: Edward Garry Richards (Soccer team, G.O. Volunteer, “The Cafeteria Staff’s favorite two years running…”) was Camera Shy.

He lay the book down on the boxes, wandered across the hall into June’s room: On the windowsill was the tepee of an empty matchbook and a white plastic flower pot still filled with earth which, June had told him yesterday, had once grown a begonia her aunt Marianne had given her two Easters ago.

In memory he refurnished the space with the pieces he’d taken upstairs the previous day and tried to pull back, also from memory, the image of June that had come to him in George’s overheard converse. Memory failed at a sound outside.

Kidd stepped back into the hall as Bobby came from the living room; he grunted, over an armful of books, “I’m taking these upstairs.”

“Why don’t you take about half of them?”

“Maybe—” two books fell—“I better.”

June came in: “Oh, hey, I’ll take some of those…” They divided the stack, left.

Where, he wondered as the door closed (the unlatched chain swung and swung over green paint), is my notebook? Of course; down the hall in what had been the back bedroom, from when he’d stopped in this apartment out of habit when he’d first come in the morning: He had momentarily forgotten that the Richards were living on nineteen now.

In the back bedroom another file box stood off center in the middle of the floor.

The notebook was on the windowsill. Kidd walked up to it, looked at the worn, smeared cardboard. Outside, small darknesses moved below the mist. What, he thought, should I say to Mr. Richards about my money? Suppose Mr. Richards comes back this evening and doesn’t bring up the subject? Kidd considered writing down alternative opening lines and rehearsing them for Mr. Richards’ return. No. No, that’s exactly the wrong way! It’s almost nine o’clock, he thought, and too smoky to tell people from shadows at seventeen stories.

Something thumped; a girl cried out. A second thump, and her pitch changed. A third—it sounded like toppling furniture—and her cry swooped. A fourth ended it.

That was from the apartment below.

Breaking glass, much nearer, brought his eyes from the floor.

Kidd went to the living room.

Mrs. Richards, kneeling over something shattered, looked up and shook her head. “I…”

He stopped before her restrained confusion.

“…I dropped one of the—”

He could not tell what the figurine had been.

“So thin—these walls are so very thin. Everything comes through. I was so startled…” By the nest tables, she picked faster in the bright, black shards, white matte overside.

“I hope it wasn’t anything you really—” but was halted by his own inanity.

“Oh, that’s all right. Here, I’ve got it all.” She stood, cupping chips. “I heard that awful…and I dropped it.”

“They were going on pretty loud.” He tried to laugh, but before her gaze, he let the laugh die in breath. “Mrs. Richards, it’s just noise. You shouldn’t let yourself get so upset about it.”

“What are they doing down there? Who are they?”

He thought she might crush the ceramic between her palms. “They’re just some guys, some girls, who moved into the downstairs apartment. They’re not out to bother you. They think the noises from up here are pretty strange too.”

“Just moved in? How do you mean, they just moved in?”

He watched her expression lurch at fear, and not achieve even that. “They wanted a roof, I guess. So they took it over.”

“Took it over? They can’t come in here and take it over. What happened to the couple who lived there before? Management doesn’t know things like this are going on. The front doors used to be closed at ten o’clock, every night! And locked! The first night they started making those dreadful sounds, I sent Arthur out for one of the guards: Mr. Phillips, a very nice West Indian man, he’s always in front of our building till one in the morning. Arthur couldn’t find him. He’d gone away. All the guards. And the attendants for the garage. I want you to know I put that in my letter to Management. I certainly did.” She shook her head. “How can they just come in and take over?”

“They just…Ma’am, there aren’t anymore guards, and nobody was living there; they just moved in. Just like you’re moving into nineteen.”

“We’re not just moving in!” Mrs. Richards had been looking about. Now she walked into the kitchen. “I wrote Management. Arthur went to see them. We got the key from the office. It isn’t the same thing at all.”

Kidd followed Mrs. Richards around the stripped kitchen.

“How do you know nobody was living there? There was a very nice couple downstairs. She was Japanese. Or Korean or something. He was connected with the university. I didn’t know them very well. They’d only been here six months. What happened to them?” She looked back, just before she went into the dining room again.

“They left, just like everybody else.” He still followed.

She carried the broken things, clacking, down the rugless hall. “I think something awful happened to them. I think those people down there did something awful. Why doesn’t Management send some new guards?” She started into Bobby’s room, but changed her mind and continued to June’s. “It’s dangerous, it’s absolutely, terribly dangerous, without guards.”

“Mrs. Richards?” He stood in the doorway while she circuited the room, hands still cupped. “Ma’am? What are you looking for?”

“Someplace to throw—” she stopped—“this. But you took everything upstairs already.”

“You know you could just drop it on the floor.” He was impatient and his impatience embarrassed him. “I mean you don’t live here anymore.”

After the silence in which her expression became curious, she said, “You don’t understand the way we live at all. But then, you probably think you understand all too well. I’m going to take this out to the incinerator.”

He ducked back as she strode through.

“I don’t like to go out in the hall. I don’t feel safe—”

“I’ll take it out for you,” he called after her.

“That’s all right.” Hands still together, she twisted the knob.

When the door banged behind her, he sucked his teeth, then went and got his notebook from the window. The blue-rimmed stationery slid half out. He opened the cover and looked at her even letters. With his front teeth set, he took his pen and drew in the comma. Her ink was India black; his, dark blue.

Going back to the living room, he stabbed at his pocket several times. Mrs. Richards came in with a look of accomplishment. His pen caught. “Mrs. Richards, do you know, that letter’s still down in your mailbox?”

“What letter?”

“You’ve got an airmail letter in your mailbox. I saw it again this morning.”

“All the mailboxes are broken.”

“Yours isn’t. And there’s a letter inside it. I told you about it the first day I came here. Then I told Mr. Richards a day later. Don’t you have a mailbox key?”

“Yes, of course. One of us will go down and pick it up this afternoon.”

“Mrs. Richards?” Something vented still left something to come.

“Yes, Kidd?”

His teeth were still set. He sucked air and they opened. “You’re a very nice woman. You’ve really tried to be nice to me. And I think it’s a shame you have to be so scared all the time. There’s nothing I can do about it, but I wish there was.”

She frowned; the frown passed. “I don’t suppose you’d believe just how much you have done.”

“By being around?”

“Yes. And also by being, well…”

He could not interpret her shrug: “Mrs. Richards, I’ve been scared a whole lot of my life too. Of a lot of things that I didn’t know what they were. But you can’t just let them walk all over you—take over. You have to—”

“I am moving!” Her head bobbed in emphasis. “We are moving from 17-E to 19-A.”

“—do something inside yourself.”

She shook her head sharply, not looking. “And you are very presumptuous if you think you are telling me something I don’t know.” Now she looked up. “Or your telling me makes it any easier.”

Frustration drove the apology. “I’m sorry.” He heard his own reticence modify it to something else.

Mrs. Richards blinked. “Oh, I know you’re just trying to…I am sorry. But do you know how terrible it is to live inside here—” she gestured at the green walls—“with everything slipping away? And you can hear everything that goes on in the other rooms, in the other apartments? I wake up at night, and walk by the window, and I can see lights sometimes, moving in the smoke. And when the smoke isn’t so heavy, it’s even worse, because then the lights look like horrible things, crawling around…This has got to stop, you know! Management must be having all sorts of difficulty while we’re going through this crisis. I understand that. I make allowances. But it’s not as though a bomb had fallen, or anything. If a bomb had fallen, we’d be dead. This is something perfectly natural. And we have to make do, don’t we, until the situation is rectified?” She leaned forward: “You don’t think it is a bomb?”

“It isn’t a bomb. I was in Ensenada, in Mexico, just a week or so ago. There was nothing about a bomb in the papers; somebody gave me a lift who had an L. A. paper in his car. Everything’s fine there. And in Philadelphia—”

“Then you see. We just have to wait. The guards will be back. They will get rid of all these terrible people who run around vandalizing in the halls. We have to be patient, and be strong. Of course I’m afraid. I’m afraid if I sit still more than five minutes I’ll start to scream. But you can’t give in to it, anymore than you can give in to them. Do you think we should take kitchen knives and broken flower pots and run down there and try to scrape them out?”

“No, of course not—”

“I’m not that sort of person. I don’t intend to become that sort. You say I have to do something? Well, I have moved my family. Don’t you think that takes a great deal of…inner strength? I mean in this situation? I can’t even let myself assess how dangerous the whole thing really is. If I did, I wouldn’t be able to move at all.”

“Of course it’s dangerous. But I go out. I live outside in it; I walk around in it. Nothing happens to me.”

“Oh, Edna told me how you got that scab on your face. Besides, you are a man. You are a young man. I am a middle-aged woman.”

“But that’s all there is now, Mrs. Richards. You’ve got to walk around in it because there isn’t anything else.”

“It will be different if I wait. I know that because I am middle-aged. You don’t because you’re still very young.”

“Your friend Mrs. Brown—”

“Mrs. Brown is not me. I am not Mrs. Brown. Oh, are you just trying not to understand?”

He gathered breath for protest but failed articulation.

“I have a family. It’s very important to me. Mrs. Brown is all alone, now. She doesn’t have the same sort of responsibilities. But you don’t understand about that; perhaps in your head, you do. But not inside, not really.”

“Then why don’t you and Mr. Richards take your family out of all this mess?”

Her hands, moving slowly down her dress, turned up once, then fell. “One can retreat, yes. I suppose that’s what I’m doing by moving. But you can’t just give up entirely, run away, surrender. I like the Labry Apartments.” Her hands pulled together to crush the lap of her dress. “I like it here. We’ve lived here since I was pregnant with Bobby. We had to wait almost a year to get in. Before that, we had a tiny house out in Helmsford; but it wasn’t as nice as this, believe me. They don’t let just anyone in here. With Arthur’s position, it’s much better for him. I’ve entertained many of his business associates here. I especially liked some of the younger, brighter men. And their wives. They were very pleasant. Do you know how hard it is to make a home?”

His bare heel had begun to sting, just from the weight of standing. He rocked a little.

“That’s something that a woman does from inside herself. You do it in the face of all sorts of opposition. Husbands are very appreciative when it works out well. But they’re not that anxious to help. It’s understandable. They don’t know how. The children never appreciate it. But it’s terribly necessary. You must make it your own world. And everyone must be able to feel it. I want a home, here, that looks like my home, feels like my home, is a place where my family can be safe, where my friends—psychologists, engineers, ordinary people…poets—can feel comfortable. Do you see?”

He nodded.

He rocked.

“That man Calkins, the one who runs the Times, do you think he has a home? They’re always writing articles about the people who’re staying with him, visiting with him, those people he’s decided are important. Do you think I’d want a place like that? Oh, no. This is a real home, a place where real things happen, to real people. You feel that way, I know you do. You’ve become practically part of the family. You are sensitive, a poet; you understand that to tear it all apart, and set it up again, even on the nineteenth floor: that’s taking a desperate chance, you see? But I’m doing it. To you, moving like this is just a gesture. But you don’t understand how important a gesture can be. I cannot have a home where I hear the neighbors shrieking. I cannot. Because when the neighbors are shrieking, I cannot maintain the peace of mind necessary for me to make a home. Not when that is going on. Why do you think we moved into the Labry? Do you know how I thought of this moving? As a space, a gap, a crack in which some terrible thing might get in and destroy it, us, my home. You have to take it apart, then put it back together. I really felt as though some dirt, or filth, or horrible rot might get in while it was being reassembled and start a terrible decay. But here—” once more she waved her hand– “I couldn’t live here anymore.”

“But if everything outside has changed—”

“Then I have to be—” she let go her skirt– “stronger inside. Yes?”

“Yeah.” He was uncomfortable with the answer forced. “I guess so.”

“You guess?” She breathed deeply, looking around the floor, as if for missed fragments. “Well, I know. I know about eating, sleeping, how it must be done if people are going to be comfortable. I have to have a place where I can cook the foods I want; a place that looks the way I want it to look: a place that can be a real home.” Then she said: “You do understand.” She picked up another ceramic lion from the nest tables. “I know you do.”

He realized it was its twin that had shattered. “Yeah, Mrs. Richards but—”

“Mom?” June said over the sound of the opening door. She glanced hesitantly between them. “I thought you were going to come right back up. Is that my shell box?” She walked to the cluster of remaining furniture. “I didn’t even know we still had it in the house.”

“Gee,” Bobby said from the doorway. “We’ve almost got everything upstairs. You want me to take the television?”

“I don’t know why,” June said. “You can’t get any picture on it anymore; just colored confetti. You better let Kidd take the TV. You help me carry the rug.”

“Oh, all right.”

June dragged the carpet roll by one end. Bobby caught the other.

“Are you sure the two of you can manage that?” Mrs. Richards asked.

“We got it,” June said.

It came up like a sagging fifteen-foot sausage between them. They maneuvered across the room—Mrs. Richards slid the nest tables back, Kidd pushed aside the television—June going forward and Bobby going backward.

“Hey, don’t back me into the damn door,” Bobby said.

“Bobby!” his mother said.

June grunted, getting the rug in a firmer grip.

“I’m sorry.” Bobby hugged the rug under his arm, reached behind him for the door knob. “Darn door…Okay?”

“You got it all right?” June asked; she looked very intense.

“Uh-huh.” Bobby nodded, backing out into the hall.

June followed him: The edge of the rug hissed by the jamb. “Just a second.” She shoved the door with her foot; and was through.

“All right, but don’t push me so fast,” Bobby repeated out in the echoing corridor.

The door swung to.

“Mrs. Richards, I’ll take the television…if you want?”

She was stepping here and there, searching.

“Yes. Oh. Certainly, the television. Though June’s right; you can’t see anything on it. It’s terrible the way you get to depend on all these outside things: Fifty great empty spots during the evening when you wish a radio or something were there to fill them up. But the static would just be awful. Wait. I could take the rest of these things off the tables, and you could carry them up. Once we get the front room rug down, I’m going to try putting that end table beside the door to the balcony. That’s what I really like up there, the balcony. When we came here, we applied for an apartment with a balcony, but we couldn’t get it then. I’m going to split these up and put them on either side of—”

Out in the hall, June screamed: a long scream he could hear empty her of all breath. Then she screamed again.

Mrs. Richards opened her mouth without sound; one hand shook by her head.

He dashed between the television and the tables, out the door.

June, dragging one hand against the wall, backed up the hall. When he caught her shoulder, the scream cut and she whirled. “Bobby…!” That had almost no voice at all. “I…I didn’t see the…” Shaking her head, she motioned down the hall.

He heard Mrs. Richards behind him, and ran three more steps.

The rug lay on the floor, the last foot sagging over the sill in the empty elevator shaft. The door nudged it, went K-chunk, retreated, then began to close again.

“Mom! Bobby, he fell in the—”

K-chunk!

“No, oh my dear God, no!”

“I didn’t see it, mom! I didn’t! I thought it was the other—”

“Oh, God. Bobby, no he couldn’t—”

“Mom, I didn’t know! He just backed into it! I didn’t see—”

K-chunk!

Kidd hit EXIT with both palms, vaulted down the flight, came out on sixteen, sprinted to the end of the hall, and beat the door.

“All right, all right. What the fuck you—” Thirteen opened for him—“banging so hard for?”

“A rope…!” Kidd was gasping. “Or a ladder. You guys got a rope? And a flashlight? The boy from upstairs, he just fell down the elevator shaft!”

“Oh, wow…!” Thirteen stepped back.

Smokey, behind his shoulder, opened her eyes wide.

“Come on! You guys got a light and a ladder? And a rope?”

A black woman with hair like two inches of Brillo with hints of rust, shouldered Smokey aside, stepped around Thirteen: “Now what the fuck is going on, huh?” Around her neck hung some dozen chains, falling between her breasts between the flaps of a leather vest laced through its half-dozen lowest holes. Her thumb hooked a wide, scuffed belt; her wrists were knobby, the back of her hands rough. Dark skin rounded above the belt and below the vest bottom.

“A boy just fell down the God-damn elevator shaft!” Kidd took another breath and tried to see past the crowd that had gathered at the door. “Will you bastards get a ladder and a rope and a light and come on! Huh?”

“Oh, hey, man!” The black woman looked over her shoulder. “Baby! Adam! Denny, you had that line! Bring it out here. Some kid fell down the shaft.” She turned back. “I got a light.” A brown triangle of stain, that looked permanent, crossed her two, large, front teeth. “Come on!”

Kidd turned away and started back down the hall.

He heard them running behind him.

As he ducked into the stairwell, Denny’s voice separated from the voices and footsteps around it: “Fell down the elevator! Oh, man,” and a barking laugh. “All right. All right, Dragon Lady—I’m with you.”

Sudden light behind him flung his shadow before him down the next flight. At the landing he glanced back:

The bright scales, claws, and fangs careened after him, striated and rigid as a television image from a monster film suddenly halted in its projector: It was the dragon he’d seen his first night in the park with Tak. He could tell because griffin and mantis glimmered just behind it, and sometimes through it. Bleached out like ghosts, the others clustered down, streaked with sidelight. Kidd ran on, heart hammering, breath scoring his nasal roof.

He fell against the bottom door; it sagged forward. He staggered out. The others ran behind. Harsh light lay out harsh shadow, dispersing the lobby’s grey as he crossed.

“How do you get down into the fucking basement?” He hammered the elevator bell.

“The downstairs is locked,” Thirteen said. “I tried to get in when we first got—”

Both elevator doors rolled open.

Dragon Lady, light extinguished, swung around him into the one with the car, wrenched away the plate above the buttons: The plate clattered on the car floor as she did something with switches. “Okay, I got both doors locked open.”

Kidd looked back—the two other apparitions swayed forward among the others standing—and called: “Where’s the rope?” He held the other jamb and leaned into the breezy shaft. Girders rose by hazy brick. “I can’t see too much.” Above and in the wind a voice echoed:

Oh, no! He’s down there! He must be terribly hurt!

And another:

No, Mom, come back. Kidd’s down there. Mom, please!

Bobby, Bobby, are you all right? Please, Bobby! Oh, dear God!.

Kidd strained to see: the vaguest suggestion of light up in the distance—was it some upper, open door? “Mrs. Richards!” His shout vaulted about the shaft. “You get back from that door!”

Oh, Bobby! Kidd, is he all right? Oh, please, let him be all right.

Mom, come back, will you?

Then lights around him moved forward, harshening the brick, the painted steel. On the shaft wall shadows of heads swung; some grew, some faded; new shadows grew.

“You see anything?” Dragon Lady asked, crowding his shoulder. “Here.” Her arm came up, hooked his. “Lean on out further if you want.”

He glanced back at her.

She said, her head to the side: “I ain’t gonna let you fall, motherfucker!”

So he hooked up his arm. “Got me?”

“Yeah.”

Their elbows made a hot, comfortable lock.

He leaned forward, swaying into the dark. She let him slowly out.

The other lights had filled the door, flushing the shaft with doubled shadows.

“You see anything in there?” which was not Dragon Lady’s voice but Denny’s.

The junk down there: On darkness like velvet, cigarette packages, chewing-gum papers, cigarettes and cigarette butts, match books, envelopes and, there to one side, heaped up…the glitter in it identified the wrist. “Yeah, I can see him…I think.”

Can you see where he is? Bobby? Bobby, Kidd, can you see him? Oh, my God, he fell all that way! Oh, he must be hurt, so badly! I can’t hear him. Is he unconscious? Oh, can’t you see where he is yet?

Momma, please come back from there!

Behind him, Dragon Lady said with soft brutality: “Christ, I wish that bitch would shut the fuck up!”

“Look, man,” Thirteen said, behind them, “that’s her kid down there!”

“Don’t ‘man’ me, Thirteen,” Dragon Lady said; and Kidd felt her grip—well, not loosen so much as shift, about an inch; his shoulder tensed. “I still wish she’d keep quiet!”

“I brought the crowbar,” somebody said. “And a screwdriver. Do you need a crowbar or a screwdriver?”

“After that fall,” Dragon Lady said, “there can’t be too much left of him. He gotta be dead.”

“Shit, Dragon Lady,” Thirteen said, “his Momma’s right up there!”