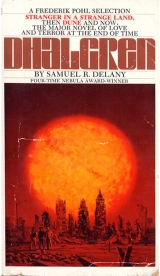

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

A Mack with a double van belched twenty feet behind him, sagged to a stop twenty feet ahead. He hadn’t even been thumbing. He sprinted toward the open door, hauled himself up, slammed it. The driver, tall, blond, and acned, looking blank, released the clutch.

He was going to say thanks, but coughed. Maybe the driver wanted somebody to rap at? Why else stop for someone just walking the road.

He didn’t feel like rapping. But you have to say something:

“What you loading?”

“Artichokes.”

Approaching lights spilled pit to pit down the driver’s face.

They shook on down the highway.

He could think of nothing more, except: I was just making love to this woman, see, and you’ll never guess…No, the Daphne bit would not pass—

It was he who wanted to talk! The driver was content to dispense with phatic thanks and chatter. Western independence? He had hitched this sector of country enough to decide it was all manic terror.

He leaned his head back. He wanted to talk and had nothing to say.

Fear past, the archness of it forced the architecture of a smile his lips fought.

He saw the ranked highway lights twenty minutes later and sat forward to see the turnoff. He glanced at the driver who was just glancing away. The brakes wheezed, and the cab slowed by lurches.

They stopped. The driver sucked in the sides of his ruined cheeks, looked over, still blank.

He nodded, sort of smiled, fumbled the door, dropped to the road; the door slammed and the truck started while he was still preparing thanks; he had to duck the van corner.

The vehicle grumbled down the turnoff.

We only spoke a line apiece.

What an odd ritual exchange to exhaust communication. (Is that terror?) What amazing and engaging rituals are we practicing now? (He stood on the road side, laughing.) What torque and tension in the mouth to laugh so in this windy, windy, windy…

Underpass and overpass knotted here. He walked…proudly? Yes, proudly by the low wall.

Across the water the city flickered.

On its dockfront, down half a mile, flames roiled smoke on the sky and reflections on the river. Here, not one car came off the bridge. Not one went on.

This toll booth, like the rank of booths, was dark. He stepped inside: front pane shattered, stool overturned, no drawer in the register—a third of the keys stuck down; a few bent. Some were missing their heads. Smashed by a mace, a mallet, a fist? He dragged his fingers across them, listened to them click, then stepped from the glass-flecked rubber mat, over the sill to the pavement.

Metal steps lead up to the pedestrian walkway. But since there was no traffic, he sauntered across two empty lanes—a metal grid sunk in the blacktop gleamed where tires had polished it—to amble the broken white line, sandaled foot one side, bare foot the other. Girders wheeled by him, left and right. Beyond, the burning city squatted on weak, inverted images of its fires.

He gazed across the wale of night water, all wind-runneled, and sniffed for burning. A gust parted the hair at the back of his neck; smoke was moving off the river.

“Hey, you!”

He looked up at the surprising flashlight. “Huh…?” At the walkway rail, another and another punctured the dark.

“You going into Bellona?”

“That’s right.” Squinting, he tried to smile. One, and another, the lights moved a few steps, stopped. He said: “You’re…leaving?”

“Yeah. You know it’s restricted in there.”

He nodded. “But I haven’t seen any soldiers or police or anything. I just hitch-hiked down.”

“How were the rides?”

“All I saw was two trucks for the last twenty miles. The second one gave me a lift.”

“What about the traffic going out?”

He shrugged. “But I guess girls shouldn’t have too hard a time, though. I mean, if a car passes, you’ll probably get a ride. Where you heading?”

“Two of us wanted to get to New York. Judy wants to go to San Francisco.”

“I just want to get some place,” a whiny voice came down. “I’ve got a fever! I should be in bed. I was in bed for the last three days.”

He said: “You’ve got a ways to go, either direction.”

“Nothing’s happened to San Francisco—?”

“—or New York?”

“No.” He tried to see behind the lights. “The papers don’t even talk about what’s happening here, anymore.”

“But, Jesus! What about the television? Or the radio—”

“Stupid, none of it works out here. So how are they gonna know?”

“But—Oh, wow…!”

He said: “The nearer you get, it’s just less and less people. And the ones you meet are…funnier. What’s it like inside?”

One laughed.

Another said: “It’s pretty rough.”

The one who’d spoken first said: “But like you say, girls have an easier time.”

They laughed.

He did too. “Is there anything you can tell me? I mean that might be helpful? Since I’m going in?”

“Yeah. Some men came by, shot up the house we were living in, tore up the place, then burned us out.”

“She was making this sculpture,” the whiny voice explained; “this big sculpture. Of a lion. Out of junk metal and stuff. It was beautiful…! But she had to leave it.”

“Wow,” he said. “Is it like that?”

One short, hard laugh: “Yeah. We got it real easy.”

“Tell him about Calkins? Or the scorpions?”

“He’ll learn about them.” Another laugh. “What can you say?”

“You want a weapon to take in with you?”

That made him afraid again. “Do I need one?”

But they were talking among themselves:

“You’re gonna give him that?”

“Yeah, why not? I don’t want it with me anymore.”

“Well, okay. It’s yours.”

Metal sounded on chain, while one asked: “Where you from?” The flashlights turned away, ghosting the group. One in profile near the rail was momentarily lighted enough to see she was very young, very black, and very pregnant.

“Up from the south.”

“You don’t sound like you’re from the south,” one said who did.

“I’m not from the south. But I was just in Mexico.”

“Oh, hey!” That was the pregnant one. “Where were you? I know Mexico.”

The exchange of half a dozen towns ended in disappointed silence.

“Here’s your weapon.”

Flashlights followed the flicker in the air, the clatter on the gridded blacktop.

With the beams on the ground (and not in his eyes), he could make out half a dozen women on the catwalk.

“What—” A car motor thrummed at the end of the bridge; but there were no headlights when he glanced. The sound died on some turnoff—“is it?”

“What’d they call it?”

“An orchid.”

“Yeah, that’s what it is.”

He walked over, squatted in the triple beam.

“You wear it around your wrist. With the blades sticking out front. Like a bracelet.”

From an adjustable metal wrist-band, seven blades, from eight to twelve inches, curved sharply forward. There was a chain-and-leather harness inside to hold it steady on the fingers. The blades were sharpened along the outside.

He picked it up.

“Put it on.”

“Are you right or left handed?”

“Ambidextrous…” which, in his case, meant clumsy with both. He turned the “flower.” “But I write with my left. Usually.”

“Oh.”

He fitted it around his wrist, snapped it. “Suppose you were wearing this on a crowded bus. You could hurt somebody,” and felt the witticism fail. He made a fist within the blades, opened it slowly and, behind curved steel, rubbed two blunt and horny crowns on the underside of his great thumb.

“There aren’t too many buses in Bellona.”

Thinking: Dangerous, bright petals bent about some knobbed, half-rotted root. “Ugly thing,” he told it, not them. “Hope I don’t need you.”

“Hope you don’t either,” one said above. “I guess you can give it to somebody else when you leave.”

“Yeah.” He stood up. “Sure.”

“If he leaves,” another said, gave another laugh.

“Hey, we better get going.”

“I heard a car. We’re probably gonna have to wait long enough anyway. We might as well start.”

South: “He didn’t make it sound like we were gonna get any rides.”

“Let’s just get going. Hey, so long!”

“So long.” Their beams swept by. “And thanks.” Artichokes? But he could not remember where the word had come from to ring so brightly.

He raised the orchid after them.

Caged in blades, his gnarled hand was silhouetted with river glitter stretching between the bridge struts. Watching them go, he felt the vaguest flutter of desire. Only one of their flashlights was on. Then one of them blocked that. They were footsteps on metal plates; some laughter drifting back; rustlings…

He walked again, holding his hand from his side.

This parched evening seasons the night with remembrances of rain. Very few suspect the existence of this city. It is as if not only the media but the laws of perspective themselves have redesigned knowledge and perception to pass it by. Rumor says there is practically no power here. Neither television cameras nor on-the-spot broadcasts function: that such a catastrophe as this should be opaque, and therefore dull, to the electric nation! It is a city of inner discordances and retinal distortions.

3

Beyond the bridge-mouth, pavement shattered.

One live street lamp lit five dead ones—two with broken globes. Climbing a ten-foot, tilted, asphalt slab that jerked once under him, rumbling like a live thing, he saw pebbles roll off the edge, heard them clink on fugitive plumbing, then splash somewhere in darkness…He recalled the cave and vaulted to a more solid stretch, whose cracks were mortared with nubby grass.

No lights in any near buildings; but down those waterfront streets, beyond the veils of smoke—was that fire? Already used to the smell, he had to breathe deeply to notice it. The sky was all haze. Buildings jabbed up into it and disappeared.

Light?

At the mouth of a four-foot alley, he spent ten minutes exploring—just because the lamp worked. Across the street he could make out concrete steps, a loading porch under an awning, doors. A truck had overturned at the block’s end. Nearer, three cars, windows rimmed with smashed glass, squatted on skewed hubs, like frogs gone marvelously blind.

His bare foot was calloused enough for gravel and glass. But ash kept working between his foot and his remaining sandal to grind like finest sand, work its way under, and silt itself with his sweat. His heel was almost sore.

By the gate at the alley’s end, he found a pile of empty cans, a stack of newspaper still wire-bound, bricks set up as a fireplace with an arrangement of pipes over it. Beside it was an army messpan, insides caked with dead mold. Something by his moving foot crinkled.

He reached down. One of the orchid’s petals snagged; he picked up a package of—bread? The wrapper was twisted closed. Back under the street lamp, he balanced it on his fingers, through the blades, and opened the cellophane.

He had wondered about food.

He had wondered about sleep.

But he knew the paralysis of wonder.

The first slice had a tenpenny nailhead of muzzy green in the corner; the second and third, the same. The nail, he thought, was through the loaf. The top slice was dry on one side. Nothing else was wrong—except the green vein; and it was only that penicillium stuff. He could eat around it.

I’m not hungry.

He replaced the slices, folded the cellophane, carried it back, and wedged it behind the stacked papers.

As he returned to the lamp, a can clattered from his sandal, defining the silence. He wandered away through it, gazing up for some hint of the hazed-out moon—

Breaking glass brought his eyes to street level.

He was afraid, and he was curious; but fear had been so constant, it was a dull and lazy emotion, now; the curiosity was alive:

He sprinted to the nearest wall, moved along it rehearsing his apprehensions of all terrible that might happen. He passed a doorway, noted it for ducking, and kept on to the corner. Voices now. And more glass.

He peered around the building edge.

Three people vaulted from a shattered display window to join two waiting. Barking, a dog followed them to the sidewalk. One man wanted to climb back in; did. Two others took off down the block.

The dog circled, loped his way—

He pulled back, free hand grinding the brick.

The dog, crouched and dancing ten feet off, barked, barked, barked again.

Dim light slathered canine tongue and teeth. Its eyes (he swallowed, hard) were glistening red, without white or pupil, smooth as crimson glass.

The man came back out the window. One in the group turned and shouted: “Muriel!” (It could have been a woman.) The dog wheeled and fled after.

Another street lamp, blocks down, gave them momentary silhouette.

As he stepped from the wall, his breath unraveled the silence, shocked him as much as if someone had called his…name? Pondering, he crossed the street toward the corner of the loading porch. On the tracks under the awning, four and six-foot butcher hooks swung gently—though there was no wind. In fact, he reflected, it would take a pretty hefty wind to start them swinging—

“Hey!”

Hands, free and flowered, jumped to protect his face. He whirled, crouching.

“You down there!”

He looked up, with hunched shoulders.

Smoke rolled about the building top, eight stories above.

“What you doing, huh?”

He lowered his hands.

The voice was rasp rough, sounded near drunk.

He called: “Nothing!” and wished his heart would still. “Just walking around.”

Behind scarves of smoke, someone stood at the cornice. “What you been up to this evening?”

“Nothing, I said.” He took a breath: “I just got here, over the bridge. About a half hour ago.”

“Where’d you get the orchid?”

“Huh?” He raised his hand again. The street lamp dribbled light down a blade. “This?”

“Yeah.”

“Some women gave it to me. When I was crossing the bridge.”

“I saw you looking around the corner at the hubbub. I couldn’t tell from up here—was it scorpions?”

“Huh?”

“I said, was it scorpions?”

“It was a bunch of people trying to break into a store, I think. They had a dog with them.”

After silence, gravelly laughter grew. “You really haven’t been here long, kid…?”

“I—” and realized the repetition—“just got here.”

“You out to go exploring by yourself? Or you want company for a bit.”

The guy’s eyes, he reflected, must be awfully good. “Company…I guess.”

“I’ll be there in a minute.”

He didn’t see the figure go; there was too much smoke. And after he’d watched several doorways for several minutes, he figured the man had changed his mind.

“Here you go,” from the one he’d set aside for ducking.

“Name is Loufer. Tak Loufer. You know what that means, Loufer? Red Wolf; or Fire Wolf.”

“Or Iron Wolf.” He squinted. “Hello.”

“Iron Wolf? Well, yeah…” The man emerged, dim on the top step. “Don’t know if I like that one so much. Red Wolf. That’s my favorite.” He was a very big man.

He came down two more steps: his engineer’s boots, hitting the boards, sounded like dropped sandbags. Wrinkled black jeans were half stuffed into the boot tops. The worn cycle jacket was scarred with zippers. Gold stubble on chin and jaw snagged the street light. Chest and belly, bare between flapping zipper teeth, were a tangle of brass hair. The fingers were massive, matted—“What’s your name?”—but clean, with neat and cared-for nails.

“Um…well, I’ll tell you: I don’t know.” It sounded funny, so he laughed. “I don’t know.”

Loufer stopped, a step above the sidewalk, and laughed too. “Why the hell don’t you?” The visor of his leather cap blocked his upper face with shadow.

He shrugged. “I just don’t. I haven’t for…a while now.”

Loufer came down the last step, to the pavement. “Well, Tak Loufer’s met people here with stranger stories than that. You some kind of nut, or something? You been in a mental hospital, maybe?”

“Yes…” He saw that Loufer had expected a No.

Tak’s head cocked. The shadow rose to show the rims of Negrowide nostrils above an extremely Caucasian mouth. The jaw looked like rocks in hay-stubble.

“Just for a year. About six or seven years ago.”

Loufer shrugged. “I was in jail for three months…about six or seven years ago. But that’s as close as I come. So you’re a no-name kid? What are you, seventeen? Eighteen? No, I bet you’re even—”

“Twenty-seven.”

Tak’s head cocked the other way. Light topped his cheek bones. “Neurotic fatigue, do it every time. You notice that about people with serious depression, the kind that sleep all day? Hospital type cases, I mean. They always look ten years younger than they are.”

He nodded.

“I’m going to call you Kid, then. That’ll do you for a name. You can be—The Kid, hey?”

Three gifts, he thought: armor, weapon, title (like the prisms, lenses, mirrors on the chain itself). “Okay…” with the sudden conviction this third would cost, by far, the most. Reject it, something warned: “Only I’m not a kid. Really; I’m twenty-seven. People always think I’m younger than I am. I just got a baby face, that’s all. I’ve even got some white hair, if you want to see—”

“Look, Kid—” with his middle fingers, Tak pushed up his visor—“we’re the same age.” His eyes were large, deep, and blue. The hair above his ears, no longer than the week’s beard, suggested a severe crew under the cap. “Any sights you particularly want to see around here? Anything you heard about? I like to play guide. What do you hear about us, outside, anyway? What do people say about us here in the city?”

“Not much.”

“Guess they wouldn’t.” Tak looked away. “You just wander in by accident, or did you come on purpose?”

“Purpose.”

“Good Kid! Like a man with a purpose. Come on up here. This street turns into Broadway soon as it leaves the waterfront.”

“What is there to see?”

Loufer gave a grunt that did for a laugh. “Depends on what sights are out.” Though he had the beginning of a gut, the ridges under the belly hair were muscle deep. “If we’re really lucky, maybe—” the ashy leather, swinging as Loufer turned, winked over a circular brass buckle that held together a two-inch-wide garrison—“we won’t run into anything at all! Come on.” They walked.

“…kid. The Kid…”

“Huh?” asked Loufer.

“I’m thinking about that name.”

“Will it do?”

“I don’t know.”

Tak laughed. “I’m not going to press for it, Kid. But I think it’s yours.”

His own chuckle was part denial, part friendly.

Loufer’s grunt in answer echoed the friendly.

They walked beneath low smoke.

There is something delicate about this Iron Wolf, with his face like a pug-nosed, Germanic gorilla. It is neither his speech nor his carriage, which have their roughness, but the ways in which he assumes them, as though the surface where speech and carriage are flush were somehow inflamed.

“Hey, Tak?”

“Yeah?”

“How long have you been here?”

“If you told me today’s date, I could figure it out. But I’ve let it go. It’s been a while.” After a moment Loufer asked, in a strange, less blustery voice: “Do you know what day it is?”

“No, I…” The strangeness scared him. “I don’t.” He shook his head while his mind rushed away toward some other subject. “What do you do? I mean, what did you work at?”

Tak snorted. “Industrial engineering.”

“Were you working here, before…all this?”

“Near here. About twelve miles down, at Helmsford. There used to be a plant that jarred peanut butter. We were converting it into a vitamin C factory. What do you do—? Naw, you don’t look like you do too much in the line of work.” Loufer grinned. “Right?”

He nodded. It was reassuring to be judged by appearances, when the judge was both accurate and friendly. And, anyway, the rush had stopped.

“I was staying down in Helmsford,” Loufer went on. “But I used to drive up to the city a lot. Bellona used to be a pretty good town.” Tak glanced at a doorway too dark to see if it was open or shut. “Maybe it still is, you know? But one day I drove up here. And it was like this.”

A fire escape, above a street lamp pulsing slow as a failing heart, looked like charred sticks, some still aglow.

“Just like this?”

On a store window their reflection slid like ripples over oil.

“There were a few more places the fire hadn’t reached; a few more people who hadn’t left yet—not all the newcomers had arrived.”

“You were here at the very beginning, then?”

“ Oh, I didn’t see it break out or anything. Like I say, when I got here, it looked more or less like it does now.”

“Where’s your car?”

“Sitting on the street with the windshield busted, the tires gone—along with most of the motor. I let a lot of stupid things happen, at first. But I got the hang of it after a while.” Tak made a sweeping gesture with both hands—and disappeared before it was finished: they’d passed into complete blackness. “A thousand people are supposed to be here now. Used to be almost two million.”

“How do you know, I mean the population?”

“That’s what they publish in the paper.”

“Why do you stay?”

“Stay?” Loufer’s voice neared that other, upsetting tone. “Well, actually, I’ve thought about that one a lot. I think it has to do with—I got a theory now—freedom. You know, here—” ahead, something moved—“you’re free. No laws: to break, or to follow. Do anything you want. Which does funny things to you. Very quickly, surprisingly quickly, you become—” they neared another half-lit lamp; what moved became smoke, lobbling from a windowsill set with glass teeth like an extinguished jack-o-lantern—“exactly who you are.” And Tak was visible again. “If you’re ready for that, this is where it’s at.”

“It must be pretty dangerous. Looters and stuff.”

Tak nodded. “Sure it’s dangerous.”

“Is there a lot of street mugging?”

“Some.” Loufer made a face. “Do you know about crime, Kid? Crime is funny. For instance, now, in most American cities—New York, Chicago, St. Louis—crimes, ninety-five per cent I read, are committed between six o’clock and midnight. That means you’re safer walking around the street at three o’clock in the morning than you are going to the theater to catch a seven-thirty curtain. I wonder what time it is now. Sometime after two I’d gather. I don’t think Bellona is much more dangerous than any other city. It’s a very small city, now. That’s a sort of protection.”

A forgotten blade scraped his jeans. “Do you carry a weapon?”

“Months of detailed study on what is going on where, the movements and variations of our town. I look around a lot. This way.”

That wasn’t buildings on the other side of the street: Trees rose above the park wall, black as shale. Loufer headed toward the entrance.

“Is it safe in there?”

“Looks pretty scary.” Tak nodded. “Probably keep any criminal with a grain of sense at home. Anybody who wasn’t a mugger would be out of his mind to go in there.” He glanced back, grinned. “Which probably means all the muggers have gotten tired of waiting and gone home to bed a long time ago. Come on.”

Stone lions flanked the entrance.

“It’s funny,” Tak said; they passed between. “You show me a place where they tell women to stay out of at night because of all the nasty, evil men lurking there to do nasty, evil things; and you know what you’ll find?”

“Queers.”

Tak glanced over, pulled his cap visor down. “Yeah.”

The dark wrapped them up and buoyed them along the path.

There is nothing safe about the darkness of this city and its stink. Well, I have abrogated all claim to safety, coming here. It is better to discuss it as though I had chosen. That keeps the scrim of sanity before the awful set. What will lift it?

“What were you in prison for?”

“Morals charge,” Tak said.

He was steps behind Loufer now. The path, which had begun as concrete, was now dirt. Leaves hit at him. Three times his bare foot came down on rough roots; once his swinging arm scraped lightly against bark.

“Actually,” Tak tossed back into the black between them, “I was acquitted. The situation, I guess. My lawyer figured it was better I stayed in jail without bail for ninety days, like a misdemeanor sentence. Something had got lost in the records. Then, at court, he brought that all out, got the charge changed to public indecency; I’d already served sentence.” Zipper-jinglings suggested a shrug. “Everything considered, it worked out. Look!”

The carbon black of leaves shredded, letting through the ordinary color of urban night.

“Where?” They had stopped among trees and high brush.

“Be quiet! There…”

His wool shushed Tak’s leather. He whispered: “Where do you…?”

Out on the path, sudden, luminous, and artificial, a seven-foot dragon swayed around the corner, followed by an equally tall mantis and a griffin. Like elegant plastics, internally lit and misty, they wobbled forward. When dragon and mantis swayed into each other, they—meshed!

He thought of images, slightly unfocused, on a movie screen, lapping.

“Scorpions…!” Tak whispered.

Tak’s shoulder pushed his.

His hand was on a tree trunk. Twig shadows webbed his forearm, the back of his hand, the bark. The figures neared; the web slid. The figures passed; the web slid off. They were, he realized, as eye-unsettling as pictures on a three-dimensional postcard—with the same striatums hanging, like a screen, just before, or was it just behind them.

The griffin, further back, flickered:

A scrawny youngster, with pimply shoulders, in the middle of a cautious, bow-legged stride—then griffin again. (A memory of spiky yellow hair; hands held out from the freckled, pelvic blade.)

The mantis swung around to look back, went momentarily out:

This one, anyway, was wearing some clothes—a brown, brutal looking youngster; the chains he wore for necklaces growled under his palm, while he absently caressed his left breast. “Come on, Baby! Get your ass in gear!” which came from a mantis again.

“Shit, you think they gonna be there?” from the griffin.

“Aw, sure. They gonna be there!” You could have easily mistaken the voice from the dragon for a man’s; and she sounded black.

Suspended in wonder and confusion, he listened to the conversation of the amazing beasts.

“They better be!” Vanished chains went on growling.

The griffin flickered once more: pocked buttocks and dirty heels disappeared behind blazing scales.

“Hey, Baby, suppose they’re not there yet?”

“Oh, shit! Adam…?”

“Now, Adam, you know they’re gonna be there,” the dragon assured.

“Yeah? How do I know? Oh, Dragon Lady! Dragon Lady, you’re too much!”

“Come on. The two of you shut up, huh?”

Swaying together and apart, they rounded another corner.

He couldn’t see his hand at all now, so he let it fall from the trunk. “What…what are they?”

“Told you: scorpions. Sort of a gang. Maybe it’s more than one gang. I don’t really know. You get fond of them after a while, if you know how to stay out of their way. If you can’t…well, you either join, I guess; or get messed up. Least, that’s how I found it.”

“I mean the…the dragons and things?”

“Pretty, huh?”

“What are they?”

“You know what is it a hologram? They’re projected from interference patterns off a very small, very low-powered laser. It’s not complicated. But it looks impressive. They call them light-shields.”

“Oh.” He glanced at his shoulder where Tak had dropped his hand. “I’ve heard of holograms.”

Tak led him out of the hidden niche of brush onto the concrete. A few yards down the path, in the direction the scorpions had come from, a lamp was working. They started in that direction.

“Are there more of them around?”

“Maybe.” Tak’s upper face was again masked. “Their light-shields don’t really shield them from anything—other than our prying eyes from the ones who want to walk around bare-assed. When I first got here, all you saw were scorpions. Then griffins and the other kinds started showing up a little while ago. But the genre name stuck.” Tak slid his hands into his jean pockets. His jacket, joined at the bottom by the zipper fastener, rode up in front for non-existent breasts. Tak stared down at them as he walked. When he looked up, his smile had no eyes over it. “You forget people don’t know about scorpions. About Calkins. They’re famous here. Bellona’s a big city; with something that famous in any other city in the country, why I guess people in L.A., Chicago, Pittsburgh, Washington would be dropping it all over the carpet at the in cocktail parties, huh? But they’ve forgotten we’re here.”

“No. They haven’t forgotten.” Though he couldn’t see Tak’s eyes, he knew they had narrowed.

“So they send in people who don’t know their own name. Like you?”

He laughed, sharply; it felt like a bark.

Tak returned the hoarse sound that was his own laughter. “Oh, yeah! You’re quite a kid.” Laughter trailed on.

“Where we going now?”

But Tak lowered his chin, strode ahead.

From this play of night, light, and leather, can I let myself take identity? How can I recreate this roasted park in some meaningful matrix? Equipped with contradictory visions, an ugly hand caged in pretty metal, I observe a new mechanics. I am the wild machinist, past destroyed, reconstructing the present.

4

“Tak!” she called across the fire, rose, and shook back fire-colored hair. “Who’d you bring?” She swung around the cinderblock furnace and came on, a silhouette now, stepping over sleeping bags, blanket rolls, a lawn of reposing forms. Two glanced at her, then turned over. Two others snored at different pitches.

A girl on a blanket, with no shirt and really nice breasts, stopped playing her harmonica, banged it on her palm for spit, and blew once more.

The redhead rounded the harmonica player and seized Tak’s cuff, close enough now to have a face again. “We haven’t seen you in days! What happened? You used to come around for dinner practically every night. John was worried about you.” It was a pretty face in half light.

“I wasn’t worried.” A tall, long-haired man in a Peruvian vest walked over from the picnic table. “Tak comes. Tak goes. You know how Tak is.” Around the miniature flames, reflected in his glasses, even in this light his tan suggested chemicals or sunlamps. His hair was pale and thin and looked as if day would show sun streaks. “You’re closer to breakfast time than you are to dinner, right now.” He—John?—tapped a rolled newspaper against his thigh.

“Come on. Tell me, Tak.” She smiled; her face wedged with deeper shadows. “Who have you brought John and me this time?” while John glanced up (twin flames slid off his lenses) for hints of dawn.

Tak said: “This is the Kid.”

“Kit?” she asked.

“Kid.”

“K-y-d-d…?”

“-i-d.”

“…d,” she added with a tentative frown. “Oh, Kidd.”

If Tak had an expression you couldn’t see it.

He thought it was charming, though; though something else about it unsettled.

She reared her shoulders back, blinking. “How are you, Kidd? Are you new? Or have you been hiding out in the shadows for months and months?” To Tak: “Isn’t it amazing how we’re always turning up people like that? You think you’ve met everybody in the city there is to meet. Then, suddenly, somebody who’s been here all along, watching you from the bushes, sticks his nose out—”