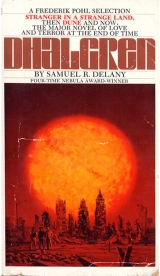

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 38 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“Wally? Of course you do. He was in the park commune. Why?”

“We murdered him yesterday.”

He thought she might move suddenly; she didn’t. “What?”

“Yesterday, one of our more retarded honkeys beat in his head with a pipe: to death. You were there. It was happening downstairs in the kitchen while we were out on the balcony.”

“It was Dollar,” Denny said.

“Lord…” she whispered, grave with shock.

“Dollar was the one you were talking to who was so—” Denny went on.

Till she interrupted: “—I remember Dollar. Wally?”

“Which one was Wally?” Kid closed his eyes.

“He was the boy who was always talking about Hawaii.”

“Oh.” Kid opened his eyes again. “Yeah. I remember.”

“He’s…dead?”

“Some stupid fight. I don’t know what happened. We were all there, and nobody—”

“I know what happened,” Denny said. “Dollar’s a fuckin’ nut! Somebody probably said something he shouldn’t’ve and Dollar didn’t know when to stop.”

Lanya sucked her teeth. “That’s Wally. Kid, that’s terrible! What’s going to happen?”

He shrugged. “Like what?”

At which point Denny drew in his breath and said, “Shit, man! You write some God-damn bloodthirsty poems. This one about the kid who fell down the elevator. Wow…”

Kid looked up at Denny.

“…‘Both legs…broken,’” Denny puzzled out, “‘pulp-skulled, jelly-hipped—’”

Kid suddenly rolled over, grabbed the book edge, and pulled it down (“…Hey, what the…!” Denny said), craning over Lanya’s lap to see the print.

But Denny had misread the line. Wildly.

Kid lay his cheek on Lanya’s and Denny’s legs.

“You all right?” Lanya asked, and Denny touched his face.

“Yeah,” Kid said. “Sure, I’m fine.” He raised his head again. “How’d you know what it was about? It doesn’t say anything about an elevator shaft in the poem.”

“I…well, I figured that’s what it…?” Denny looked surprised. “…had to be about. I mean I was there, remember?”

“Oh.” Kid put his cheek down. “Yeah.”

“Is Dollar still over with the scorpions?”

“Yeah.”

“Is he all right?”

“If Copperhead doesn’t decide to kill him. John and Milly came over with a delegation this morning. To protest. I started to yell at Dollar. Just yell, that’s all. Just to find out what had happened. He’s not really all there, and you have to talk loud to get through, you know? And they started to get squeamish.”

Lanya said: “I’ve never believed in capital punishment either. And Wally wasn’t the most popular person around. Rap, rap-rap-rap-rap: He could be annoying—”

“That’s not the point—”

“I know! I know, believe me. I know.” She rocked him, bending above. “I mean I just…”

“You don’t believe in capital punishment as long as there’re mental hospitals, right? With violent wards. Well, we don’t have any violent wards. We don’t have any jails either.”

“But you have to—”

“Look.” Kid pushed himself up and twisted around “I don’t believe in capital punishment period! I think if one person kills somebody else because he gets his rocks off, or he just wants to, that’s…well, maybe not right. But a bunch of people getting together and deciding to kill somebody else because it’s anything from right to expedient, is wrong!”

“Lord,” Lanya said again. “Donatien Alphonse François de—”

“What?” Denny said.

“Never mind.” She pushed the covers down. “Let’s go for a walk or something. I’m not sleepy anymore.”

Kid suddenly reached across to yank Denny’s hair.

“Hey—!”

Kid pulled the boy down. Denny dropped the book and grabbed at Lanya’s arm. “What the fuck—”

“You like my smell?”

Lanya said, “Hey, what are you—” and backed away, frowning.

Denny’s arm flapped. Kid caught it with his other hand and forced the head into his lap. “Come on, you like it?”

“Shit!” Lanya tugged Kid’s wrist. “Let go of him!”

“Hey…!” Denny laughed loudly, nervously, and pulled; couldn’t get loose, and yelled a little. “Come on, lemme—”

“You like it, you little bastard!”

Denny held onto Kid’s hip and twisted his face.

“Yeah…!”

“Kid, will you stop that, for God’s—”

Kid suddenly let go, held both his hands in the air. “See?”

Denny put his other arm around Kid’s other hip. His face against Kid’s jeans, he took a breath.

“It’s okay when I do him like that,” Kid said to Lanya. “He likes it. You like it, don’t you?”

“Fuck you,” Denny said. “Yeah, I like it.”

“You like my smell?” Lanya suddenly swung up on her knees. One knee went above Kid. She grabbed him by the ears. He started to say, “Hey…” but let it turn into a roar, and raised his head to muffle it between her legs. She bent and locked her arms behind his head. “You like my fucking smell? Yeah, you like it…” and then she laughed and fell over on her side. The bed’s feet bounced.

He said, “Yum yumyumyumyum,” as fast as he could. Her legs were warm and blocked his ears. A ligament defined itself across his jaw.

Still laughing, she said, “I don’t think I can keep the rough act up as long as you can, though.”

He got his mouth free. “I like it anyway. For breakfast, for lunch, for dinner…”

“Hey.” Denny’s face appeared above Lanya’s thigh. “Ain’t we making a lot of fucking noise? What sort of patient she got in there anyway?”

“Jesus…” Lanya laughed.

“She’s a shrink,” Kid said. “She’s a God-damn fucking headshrinker. She takes crazy people like us and makes us all better.”

“I want to go for a walk,” Lanya said. “Will you two please get up and let me put my pants on?”

“She’s really a headshrinker?” Denny asked. “She got some crazy man in there?”

“Yes,” Lanya said. “Now will you please move your ass off my foot?”

“You just don’t want to ball,” Kid said.

“Not true. I just do want to get some air.”

Kid rocked up, stood. “Okay. Fine. Who can ball with all these Venus fly traps leering at you anyway?” And realized they made him feel far more uncomfortable than he could, comfortably, admit. On the desk in the bay window lay his notebook.

“Fine reason to get out of here,” Lanya said.

“I dropped my book behind the bed,” Denny said. “Just a…eh…there, I got it.”

Kid went to the desk and opened the grimy cover. Folded inside was the sheet from the telephone pad, grilled with his handwriting.

“And the galleys with your corrections are in the top drawer on the right.” The last of her sentence was muffed by the T-shirt coming off. “Mr. Newboy gave me everything just before he left, when we didn’t know where you were.”

Kid sat down on the chair’s torn caning.

Quickly he flipped through till he found a three-quarter-blank page. He pulled loose his pen. The raddled pages chattered at the pressure of his ball-point. He wrote very quickly, with his face screwed; his lips parted across his teeth, then pressed together again. Where his spine settled in the sacrum’s socket, a suspended tension began to release. Neither he nor it had finished when Denny, behind him, said: “Kid?”

But he closed the notebook cover over the page. Then he turned around. Lanya, sitting on the bed in her jeans and sneakers, but no shirt, looked up from the book of poems.

Denny stood in the middle of the room, one hand flat on his thigh. “I…mmm…you said…I wanted to tell you, Kid, that, well, when you go on like that with me and call me names and stuff and push me around, I guess I don’t mind it.” He looked down and swallowed. “But I don’t like it that much.” The inflection of the sentence didn’t resolve, so he added, “…you know?”

Kid nodded. “Okay.”

Denny swayed a little, uncomfortably. Suddenly Lanya put the book on the floor, and walked up behind him. She put her chin on his shoulder, her arms around his stomach. Denny put his forearm along hers, rubbed the back of her wrist, and waited.

Kid went and put his arms around both of them; Lanya’s bare back under his hands was very warm. One of them held on to his waist. After a moment Denny said: “You’re both in the wrong position. Him in front and you on my ass, I don’t get a chance at nothing—Hey…” And pulled Kid close again when he started to back off. Lanya, head bent, hair brushing Kid’s nose over Denny’s shoulder, looked up with wide, wide eyes—brighter than any leaf about them. Kid blew at her nose. Denny wriggled. “I don’t think three people can kiss each other at the same time…” he said.

“Yes we can,” Lanya said. “Here, see…”

A minute later, heads together, arms locked around one another’s backs, Kid said, “This is comfortable.”

“I think,” Denny said, moving his head down between their chins, “I smell more than either of you.”

“Mmm…” Lanya nodded.

“Didn’t you say something about wanting to go out?” Kid asked.

She nodded again. “Mmmm? Let’s go.”

First cold air under his left arm, then his right. Her fingers on his chest were the last to leave him.

He looked at the desk and wondered whether he should take the notebook.

“You sure keep it hot in here,” Denny said.

“Oh, would you turn that off for me?”

“How?”

“Never mind. I’ll do it.”

Kid looked up: Lanya squatted before the heater, grunting and twisting at something inside.

“There.” She stood. “Let’s go.”

“You ain’t gonna put no shirt on or nothing?” Denny asked.

The sides of the heater, cooling, clanged.

“Be a doll and let me wear your vest?”

“Sure,” Denny shrugged out of his. “But it won’t cover your tits.”

“If I wanted them covered, I’d put on a shirt.” She took the vest from him. “There’s some advantages to living in this city.”

“You’re a funny lady.”

“You’re a funny boy.”

Denny bit on his lip a moment, then nodded deeply. “I guess I sure as fuck am.”

“What are you grinning about?” Lanya asked Kid.

“Nothing,” and ended up grinning harder. “You gonna take up chains too and be a member…”

She considered a moment, sucking her underlip. “Nope.” One nipple was just visible inside the leather lapel. The other was covered. “Just curious.” And picked up her harmonica from the floor by the bed.

They play me into violent postures. Adrift in the violent city, I do not know what stickum tacks words and tongue. Hold them there, cradled on the muscular floor. Nothing will happen. What is the simplest way to say to someone like Kamp or Denny or Lanya that all their days have rendered ludicrous their judgments on the night? I can write at it. Why loose it on the half-day? Holding it in the mouth distills an anger, dribbling bitter, back of the throat, a substance for the hand. This is not what I am thinking. This is merely (he thought) what thinking feels like.

They were quiet through the living room. At the head of the steps Denny began giggling. Lanya hurried them down. They reached the porch, hysterical.

“What’s so funny?” she asked three times; three times her face recovered from the contortions of mirth.

Kid thought: There’s a moment in her laughter when she’s very ugly. He watched for it, saw it pass again, and found himself laughing the harder. She took his hand, and he was very glad she did. The stridence smoothed in his own voice.

Denny’s leveled, too, from some relief Kid did not understand.

“Where’s your school?” Kid asked.

“Huh?”

“Denny told me you were teaching in a school. And Madame Brown said something about classes.”

“You told me about the school,” Denny said.

“It’s right down there. That’s where we’re going now.”

“Fine.”

She bit both lips and nodded; then slid her arm up to link Kid’s elbow, held out her other hand to Denny…who pretended not to see and tight-roped along the curb. So she dropped Kid’s hand too.

The green jacket was new. The shirt between the brass zippers looked old. He came from the corner, unsteadily, head slightly down. His varying steps took him indiscriminately left or right. Twenty-five? Thirty? His black hair was almost shoulder length. In the bony face there was nothing like eyes. He…staggered closer. Tiny lids were pursed at the back of fleshed-over sockets otherwise smooth as the insides of teacups. One leaked a thread of mucus down his nose. He came on, missing the lamppost by a lucky detour. On twine around his neck hung a cardboard sign, lettered in ballpoint:

“Please help me. I am deaf and dumb.”

Denny stepped closer to Lanya and took her arm. The blind-mute passed. “Wow—” Denny started, softly. Then breath stopped.

The heavy blond Mexican in the collarless blanket-shirt hurried from a doorway. The irregular tap of the blind-mute’s cowboy boots stopped when the Mexican seized his shoulder; his head came way up and swung in the air like sniffing as the Mexican took the blind-mute’s hand. He pressed in his fist against the mute’s palm, and pressed again, and pressed again, making different shapes. The blindmute nodded. Then they hurried to the corner, holding one another’s arm.

“Shit…” Denny said, wonderingly and lingeringly. He looked at Lanya. “We seen him before, you know? The big spic. He pushed Kid, you know? Just came to him in the street and pushed him.”

“Why?” Lanya asked. She reached across to hold the right lapel of Denny’s vest with her left hand.

“Don’t tell me everything in this fucking city happens for a reason,” Kid said. “I don’t know.”

“Well,” Lanya said, “usually, in Bellona, everything happens for…” Then she sucked her teeth. “Deaf and blind? That’s heavy. I was in San Francisco once. You know the welfare office on Mission Street?”

“Yeah,” Kid said, “I tried to get on welfare out there, but they wouldn’t let me.”

She raised an eyebrow. “I was walking by it once…reading the signs on the Page Glass Company…? When I looked down, I saw a dumpy woman in a flowered house dress leading this old man who was tapping a cane. But when she got to the steps, she stooped down to feel around. And she was saying, ‘Now I know…I know where it is.’ Three more steps, and I realized she was blind, too. I watched them till she finally got them through the door. It was fascinating, and a little horrifying. But when I went on, I began to think: What a marvelous image for most of human history, not to mention current politics. Practically every relationship I know has something in it of—and then of course it struck me, and I began to laugh right there on the street. But the point is, it really hadn’t occurred to me all the time I’d watched them. And all I could do was think how lucky I was that I had decided not to be an artist, or a writer or a poet. Because how could you use a perfectly real experience like that in a work of art today, you know?”

“I don’t get it,” Denny said. “What do you mean?” (Without Denny’s vest, Kid noticed one of the five chains Denny wore was copper. His back and shoulders, here and there pricked with pink, looked white as stone.)

“It’s just that…” Lanya frowned. “Well, look, Denny—you’ve heard the expression…”

He hadn’t.

When they’d tried to explain for a block and a half, Kid realized that Denny was now between them once more (“But why can’t you use something anyway that somebody already said?” Denny demanded once more. “I mean if you say where you got it from, maybe…”), but Kid could not remember switching positions: gruffly he switched back.

“That’s the school.” Lanya squeezed Kid’s arm. “It doesn’t look like one, I know. But I guess that’s the point.”

“It looks like a drug store,” Denny said. “I wouldn’t want to put a school in no place that looked like a drug store. I mean not around here.”

“It was a clothing store,” Lanya said.

“Oh.” Denny’s tongue made a hillock on his cheek. “It sure looks like a drug store.”

“I hope not.” Lanya actually sounded worried.

“I don’t think it should look like any sort of store at all,” Kid said. “I mean if you don’t want people busting in.”

“That was the idea,” Lanya said. “I didn’t think it looked like a store at all. At least since we took the sign off. Just a house with a large front window. There isn’t any writing on it.”

“I seen drug stores like that.” Denny nodded in self-corroboration. “People around here are always busting into drug stores and doctors’ offices ’cause they think they can find shit. And they find some, too.”

Lanya jiggled the handle. “I thought it looked like a coffee shop.” The door swung in.

Turning inside, Kid saw curtains in front of the window. Light prickled the weave. “I didn’t notice those from the outside.”

“That’s because the window’s so dirty it really doesn’t matter.”

“It sure is dark,” Denny muttered. “You got electricity here, don’t you?”

“There’re lanterns,” Lanya said. “But I don’t think we’d better use them now.”

“Put your lights on,” Kid told Denny. Denny’s hand rattled in chains.

Lanya’s hand leapt to shadow her face. “…that surprised me!” She laughed.

Shadows from the chairs swung on the linoleum as what had been Denny moved toward a blackboard stand. “It sure looks like a school inside.”

“Actually started out just as a day-care center. You have no idea how many children there are in Bellona! We don’t either. They don’t all come here.”

“You take care of them while their parents go to work?” Kid asked.

“I really don’t know what their—” she glanced at him, closed her lips, moved them across her teeth—“what their parents do. But the kids are better having each other to play with some place where it’s safe. And we can teach things here. Things like reading; and arithmetic. Paul Fenster got the thing started. Most of the kids in my section, in all the sections really, are black. But we’ve got three white children who’re holed up with their parents over in the Emboriky department store.”

“Shit,” Denny said. “You take those bastards?”

“Somebody has to.”

“I don’t think I’d fall in love with any of them.”

“Yes, you would. They’re all cute as the devil.” She picked up a lantern that had dropped from its nail and hung it back. “When Paul suggested that I take over a section, at first I really wondered. I’m not a social crusader. But you wouldn’t believe how good these kids are. And quiet? With a bunch of seven, eight, and nine year olds, it’s a little unnerving just how quiet they can be. They do practically anything I say.”

“They’re all probably scared to death.”

Lanya made a face. “I’m afraid, really, that’s what it is.”

“Of you?” Denny’s great light bobbed.

“No.” Lanya frowned. “Just scared. It was my idea to try actually teaching something…just to pass the time. It works out a lot better than letting them run loose—mainly because they don’t run.” She blinked. “They just sat around and fidgeted and looked unhappy.” She turned to the table. “Well, anyway, here—”

The aluminum face of a four-spool tape recorder, interrupted with a quorum of dials, twin rows of knobs, tabs, and multiple ranks of jack-sockets, gleamed above coiled wire, on which lay three stand-mikes and several earphones.

“…since you’re here—” Lanya sat one rod-mike upright—“you might as well help. I was going to try something out that I’ve been working on—Denny, if you’re going to keep that thing on, please be still! It’s distracting!”

“Okay.” A chair rasped back. Denny’s light, quivering, lowered about it; and consumed it. “Okay. What do we do?”

“You can start off by keeping quiet.” She pressed a switch; two spools spun. “Then it gets more complicated. This is a great machine. It’s two free and reversible four-track recorders on one chassis, with built in cell-sink.” She pressed another tab; the spools slowed. She blew a run on the harmonica toward the mike, pressed the off button. Another finger went down on a black tab. The spools halted, reversed; another finger went down.

The spools slowed, stopped.

Another finger.

They reversed.

From under the table—Kid’s eyes jerked down to the metallic-shot speaker cloth—the harmonica, twice as loud and with echo, rang like a mellophone.

Lanya turned a knob. “Level’s a little high. But that’s the effect I want for the third track.”

The tape ran back (more tabs: chud-chuk), reversed. Lanya blew another run, and replayed it.

“Gee,” Denny said. “On the tape, it sounds just like you playing.”

No, Kid thought. It sounds entirely different. He said: “It sounds pretty good.” But different.

Lanya said: “It’s about okay.” She turned one knob a lot, and another only a little. “That should do it.” She pressed another tab. “Here goes nothing. Be quiet now. I’m recording.”

Denny’s chair leg squeaked on the floor.

Lanya scowled back over her shoulder and positioned herself at the mike. Without lifting her sneaker heel, she began swinging her knee to keep time. Her shoulders rounded from the armholes of Denny’s vest. She blew a long, bending note. And another. A third seemed to slide from between them, bent back, hung in the half-dark room—light glowed in three of the dials; red hairlines shook—and turned over, became another note, did something to Kid’s eyebrows so they wrinkled. And Denny had turned off his shield.

She played.

Kid listened, and remembered crouching in dim leaves, leaves tickling his jaw, while she walked beyond him, making bright music. Then something in the playing brought him to the here and now of the room, the plastic reels winding, the tension-arm bouncing inside its tape loop, the needles swinging, three (of the four) signal lights glowing like cigarettes. The music was more intense than memory; emotional fragments, without referent scenes, resolved through the brittle, slow notes. She moved her mouth and her forehead; her two forefingers rose vertical over the silver (her nails were slightly dirty; the music was wholly beautiful), then clamped. Silver slid between her lips. She played, played more, played some phrase she’d played before, then turned the tune to its final cadences, taking it to some unexpected key, and held and harped on the resolving chord sequence; a little trill of notes kept falling into it, every two beats; and falling; and falling.

She dropped the harp, clutching it in both hands, against her bare breasts, and grinned.

After maybe ten seconds, Denny applauded. He stuck out his legs from the chair, bounced his heels, and laughed. “That’s pretty good! Wow! That’s pretty nice!”

Kid smiled, pulled his bare toes back on top of his boot, pushed his shoulders forward; in his lap his hands knotted. “Yeah…”

Lanya grinned at them both, stopped the tapes. “I’m not finished yet. You guys have to help on the next part.” She plugged in one earphone set, tossed it to Denny: “Don’t drop—”

He almost did.

She started to toss another set to Kid; but he got up and took it. Tangled cords swung to the floor. “I’m going to lay in another track on top of it. Remember that little part just before the end? Well, this time you have to clap there, five times, each time a little louder. And sort of shout or hoot or something on the last clap.” She played the section over.

Denny started to beat his hands together.

“Just five times,” she said. “Then shout. I’ll bring you in. Let’s try it.” They did. Denny hooted like a choo-choo train, which broke Kid up laughing.

“Come on,” Lanya said. “You guys don’t have to overdo it!”

They tried again.

“That’s it. Put your earphones on, and we’ll lay it in.”

The rubber rims clasped Kid’s ears and damped the room’s silence down a level.

“I’m going to be playing something entirely different.” Lanya’s voice was crisp and distant through the phones. “But I’ll signal you two in with my elbows.” She flapped one at them and put on her own phones. The vest swung from her sides. “There we—” she turned on the tape. Momentarily the silence in Kid’s phones crackled—“go.”

Kid heard Denny’s chair leg squeak; but it was on the tape.

Then, a long note bent.

Over it, Lanya began, as the beat cleared, to rattle out, like insects, high triplets, first here, then up half a step, then down a whole one. Her mouth jerked across the organ and she dragged a growl up from the windy lower holes. Then jerk: bright triplets rattled. The old melody wound, beneath them and decorated by them: each time the third batch arrived, they thrust it into a new harmony, and toward Kid’s and Denny’s cadenced entrance:

Denny leaned forward, eyes wide, hands out and up, cradling an invisible globe. Kid’s fingertips tickled his palm…His head was down, to feel the rhythm; his eyes were wedged at the top of his sockets, to watch her.

Lanya swung her whole body back and brought both elbows in to her sides.

Denny’s globe collapsed.

Kid’s palm stung. And stung again. And again. And again—the sound, and his head, rose—and again: his face burst with noise and sudden joy.

Through the phones, from under his own cry, the rough fabric of the ending, with the little trill falling into it again and again, secured in its foreign key, brought all to its proper close.

Denny, still seated, looked about to explode. And, after five seconds shouted: “Whoop-eee!” and bounced in his chair.

“You like that, huh?” Lanya grinned over her shoulder, ran the tape back. “I want to lay in one more track. You guys have to do the same thing again.” To Denny’s frown, she explained: “Because I want it to sound like a whole room full of people clapping, not just you two. See if you can shout on a different note. I mean, if you hooted high before, hoot low. And vice versa.”

“Sure,” Denny said. “Where’d you learn to do this?”

“Shhh,” Lanya said. “Let’s just do it. I don’t have too much to play on the harmonica this track. But don’t let what I do throw you off.”

Kid nodded, pulled apart the phones at his ears—two rings of perspiration cooled—then let them clamp back.

“Here we go.” She glanced back. “Ready?”

The crackle…

The chair squeak…

Then the long note, bending…

Lanya reinforced the first phrase with middle notes, dropped the harp from her mouth, took a step back, and whistled a phrase over the quiet beginning. One of the harmonicas, already recorded, took it up. Kid suddenly understood the movement between soft and loud built into the two tracks already down; Lanya whistled again. Again the harmonicas carried the whistling into their organ-like development. She put the harp to her mouth, gave some bass strength to another section, waited, glanced at Kid, at Denny. Another thirty seconds of music gathered itself together: suddenly she whistled shrilly, and her elbows came down.

Kid and Denny clapped.

So did Lanya, taking a large step back from the mike, bobbing her head and whacking the back of her harmonica hand against her palm. They clapped through the ringing five, and all shouted together with the voices already taped. Once more Lanya was at the mike, harp at her mouth, weaving high shatter-notes through the ending tapestry.

Then silence.

She said, softly, breathing hard: “There…” and pressed a button. The tapes halted.

“Jesus…!” Denny stood. “That’s wild! Where’d you get the tape recorder? I mean, how’d you learn—”

“Paul borrowed it from Reverend Taylor for me.”

“You do a lot of that stuff before?” Denny asked.

“Nope.” Lanya took off her own earphones, hung them over the mike’s jutting bar. “It’s just something I wanted to try out. I’ve worked with tapes before but—”

Kid said: “Let’s hear the whole thing!” Taking off his earphones, he came up beside her.

“What are you gonna call it?” Denny clacked his earphones down on the table.

“—Watch it,” Lanya said. “Those are delicate.”

“Sorry—What’s its name?”

“For a while—” she ran her thumb across Kid’s chest—“I was thinking of calling it ‘Prism, Mirror, Lens.’ But then—” Denny disappeared in his ball of light; Lanya squinted, stepped back—“what with that big thing we saw up in the sky…I don’t know. Maybe I’ll just call it ‘Diffraction.’ I like that.”

Holding his lips between his teeth, Kid nodded. “Go on.” His lips came loose and tingled. “Play it.”

Denny turned on like a frozen node of incandescent gas, moved center floor.

Tapes turned.

“Here we go…”

Denny stilled.

“…I want you to note—” Lanya lay her harmonica on the table, then raised one finger—“that something like that usually takes six or eight hours to do; we have been at this no more than two hours.”

From the speakers beneath the table, Denny’s chair leg squeaked.

Kid put his own phones down softly and listened (thinking: Temporal diffraction? Two hours? It had seemed perhaps twenty minutes!):

The long note bent.

Somehow, lost in a machine, I have been able to grasp and strip from the body of experience three layers of living thesis: She inscribed them with her music, laid them over one another so that, thinned by tape and transistors, their transparent silences and aural aggregates, as she, the inventor, conceived them, clear for me, the invented one, at last. (On the tape Lanya whistled and played with her own whistling, the harmonica cradling its brittle, upper notes with low, breathy ones.) Is that where it goes (thinking:) when it goes? This is melody and there—the shrill whistle which Kid realized now was the real, musical signal for the clapping to begin—which began! He listened to a room full of people clap in time. One of the tracks was heavily echoed and made the clapping seem to come from dozens. The claps mounted; a final clap, and the dozens shouted—among them he recognized his own voice, and Denny’s, and Lanya’s; but there were many others. Their shouts died over a discord no single harmonica could make.

But probably any three could.

The finale cleared in its higher, supporting key; trills of notes fell into, and trills of notes rose out of, the moaning chord. The sound clutched at him, tightened his stomach.

Lanya listened, arms at her sides, head down, frowning with concentration. The white pips of her upper teeth dented one side of her lip.

The piece ended.

She still listened.

Then Denny applauded and laughed. Another Denny, on top of him, shouted, “Whoop-eee!” And Denny across the room, encased in light, said: “Hey, you know we got company in here? Look back there…”

Lanya’s head came up suddenly. She turned off the tape.

Denny’s light was over near the darkened corner. “Back behind the blackboard there.”

“Huh?” Kid stepped forward.

“There’s a big old nigger bitch in here, and, man, she’s about to shit!”

“Denny!” Lanya exclaimed, and ran through the edge of his light, which turned, laughing, after her.

Kid pushed away the blackboard, looked down.

The board-stand’s wheels stopped creaking.

The woman wore a black hat and a black coat, hem rumpled on the floor around her. She blinked up at them, feeling for the string handles of the shopping bag beside her. Catching the bag up, she breathed a word all wind.

“What do you want?” Lanya asked. “Are you…all right?”